Style Handout 4/3

advertisement

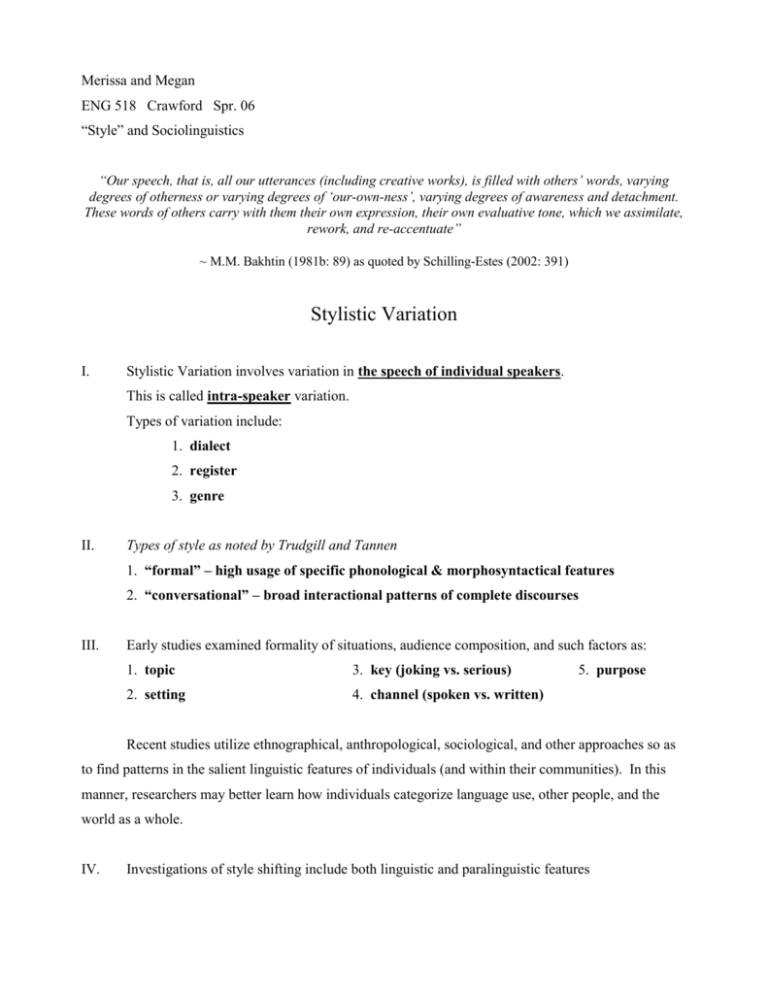

Merissa and Megan ENG 518 Crawford Spr. 06 “Style” and Sociolinguistics “Our speech, that is, all our utterances (including creative works), is filled with others’ words, varying degrees of otherness or varying degrees of ‘our-own-ness’, varying degrees of awareness and detachment. These words of others carry with them their own expression, their own evaluative tone, which we assimilate, rework, and re-accentuate” ~ M.M. Bakhtin (1981b: 89) as quoted by Schilling-Estes (2002: 391) Stylistic Variation I. Stylistic Variation involves variation in the speech of individual speakers. This is called intra-speaker variation. Types of variation include: 1. dialect 2. register 3. genre II. Types of style as noted by Trudgill and Tannen 1. “formal” – high usage of specific phonological & morphosyntactical features 2. “conversational” – broad interactional patterns of complete discourses III. Early studies examined formality of situations, audience composition, and such factors as: 1. topic 3. key (joking vs. serious) 2. setting 4. channel (spoken vs. written) 5. purpose Recent studies utilize ethnographical, anthropological, sociological, and other approaches so as to find patterns in the salient linguistic features of individuals (and within their communities). In this manner, researchers may better learn how individuals categorize language use, other people, and the world as a whole. IV. Investigations of style shifting include both linguistic and paralinguistic features ______Linguistic Paralinguistic___ Nonlinguistic_______________ 1. phonological 1. intonation 1. hair 2. morphosyntactic 2. clothing 3. lexical 3. make-up 4. pragmatic/interactional 4. body positioning 5. use of space 3 Major Approaches to Stylistic Variation A. Attention to Speech I. William Labov conducted the first investigations through sociolinguistic interviews in order to capture “casual” and “natural” speech not altered by the presence of an observer. Paralinguistic Channel Cues – changes in: 1. tempo 3. volume 2. pitch 4. breathing rate 5. use of laughter Labov believed style shifts came about based on how much people exercised attention to their speech – i.e. self-consciousness. Patterning – stylistic variation parallels social class variation II. Bell’s Style Axiom: Variation on the style dimension within speech of a single speaker derives from and echoes the variation which exists between speakers on the “social” dimension Exceptions to patterning 1. Statistical hypercorrection – use of higher rather than lower levels of standard variants in middle class vs. upper class in more formal styles 2. “Hyperstyle” variables – show far more stylistic variation than social class variation for all social groups 3. Hyperdialectism (Trudgill) – overgeneralizing into environments where highly noticeable features of dialect contact aren’t linguistically expected III. Limitations to Attention to Speech Approach 1. Separation of casual vs. careful speech is difficult 2. Channel cues are unreliable 3. Level of formality can’t be correlated with attention to speech B. Speaker Design Approach I. Under this approach, stylistic variation is examined through “the active creation, presentation, and re-creation of speaker identity.” Identity encompasses personal as well as interpersonal dimensions. II. Speaker Agency – why people make stylistic choices Factors that can influence language choice: III. 1. audience 3. setting 5. key 2. topic 4. purpose 6. frame *purpose, key, frame are speakerinternal The importance of phonological variants - carry connotations of group belonging – particular attributes of group (not group as whole) - individuals, idealizations IV. Social Definition - stylistic variation leads to social change - define situations and groups V. - groups and individuals change styles as usage progresses Limitations to Speaker Design Approach 1. (Bell) – not predictable, but interpretable 2. (Coupland) – audience-related, attention-related, interplay of message content, status relationships, role relationships, linguistic function, linguistic form 3. Generalization is inappropriate because we are looking at intra-speaker variational patterns, not patterns in existence across social groups. Eckert (2000: 69): “The challenge in the study of the social meaning of variation is to find the relation between the local and the global – to find the link between speakers’ linguistic ways of negotiating identity and relations in their day-to-day lives, and their place in the social stratification of linguistic variation that transcends local boundaries.” – As quoted by Schilling-Estes (2002: 393) C. Audience Design Approach I. Style shifting occurs in response to audience members, not from self-consciousness toward speech. The basis of this approach is Speech Accommodation Theory. II. Convergence and Divergence III. 1. Speech rate 3. Pausing 2. Content 4. “Accent” Other Audience Members 1. Auditors – ratified participants not directly addressed 2. Overhearers – non-participants known to be within hearing range 3. Eavesdroppers – unratified people not known to be present IV. Dimensions of Audience Design 1. Responsive – speech is shaped in response to addressee(s) 2. Initiative – particular motivation to use particular speech in particular situation with addressee V. Limitations to Audience Design Approach 1. Heavy reliance on the responsive dimension. 2. Unclear on identifying marked (unexpected) vs. unmarked (expected) style, as they can both create meaning 3. Personal characteristics – Responding to ethnicity? Familiarity? Age? Gender? Individual Personality? 4. Too unidimensional – Topic effects derive from audience effects? The Future Stylistic variation is essential in creating and projecting (performing) one’s personal identity. Listener perception must also be taken into account; when do people notice style shifting and how do they interpret such shifting? Are patterns apparent and interpretable? These questions and concerns about identification through language use are all part of what linguistics view as the very start of finding the meaning of “style.”