Polar Ice Feels the Heat

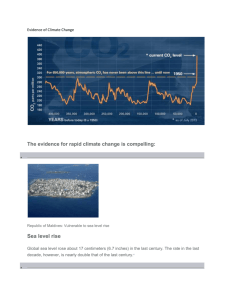

advertisement

Polar Ice Feels the Heat Agnieszka Biskup April 23, 2008 Glaciers have retreated dramatically all over world. Here are some photos of Alaska’s Muir Glacier, photographed by glaciologist William O. Field on 13 August 1941 (left) and by geologist Bruce F. Molnia on 31 August 2004 (right). National Snow and Ice Data Center, W. O. Field, B. F. Molnia. Can you feel the world getting warmer? Maybe you can’t, but ice across the planet’s surface has certainly been feeling the heat, according to new reports. Indeed, the dramatic shrinkage of Arctic ice—and at some spots, its seasonal near disappearance—is one sure sign that our planet has developed a fever. So are glaciers—and not only at the poles. Around the world these massive moving fields of ice have been posting record losses. The World Glacier Monitoring Service, based at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, looked at nearly 30 reference glaciers in nine different mountain ranges across the globe. In March, its scientists reported disturbing news. The average melting and thinning rate of those glaciers has more than doubled between the 2004 and 2006. “The latest figures are part of what appears to be an accelerating trend with no apparent end in sight,” said Wilfried Haeberli, who directs the glacier-monitoring group. In Antarctica, a large chunk of the Wilkins Ice Shelf recently collapsed into the sea. Satellite images show the Wilkins Shelf began falling apart in late February, when a large iceberg 41 kilometers by 2.5 kilometers (25.5 miles by 1.5 miles) broke away from the shelf. This triggered a runaway disintegration of an additional 405 square kilometers (160 square miles) of the shelf. The total loss was 8.5 times the area covered by New York’s Manhattan Island. As of March 23, only a 6 km (3.7 mile) wide strip of intact ice was protecting the shelf from further collapse. Scientists from the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center and the British Antarctic Survey put the blame for the Wilkins’ massive melt-triggered event on a warmer world. “We believe the Wilkins [Shelf] has been in place for at least a few hundred years,” said Ted Scambos, a lead scientist with the snow and ice data center. “But warm air and exposure to ocean waves are causing a break-up.” With strong evidence that ice is melting globally atop mountains and at Earth’s poles, scientists say that it’s pretty clear our planet is warming. And that could spell big changes even in regions where the only ice you’d normally encounter is in a beverage. A series of satellite images showing the Wilkins Ice Shelf as it begins to fall apart. National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, CO Arctic ice on the rocks Changes in the Arctic’s sea ice offer more cause for concern. That’s the March 18 conclusion of a team of federal scientists who performed a recent checkup on this cold region. The Arctic is a normally ice-covered ocean surrounded by land. Sea ice grows and shrinks seasonally—building throughout the cold, sunless winter and then melting somewhat during the sunny, warmer summer. Satellite data has shown that a colder-than-average winter this year has actually increased the amount of the Arctic’s new—or seasonal—ice. However, some ice in this region can last for up to 10 years. This older—or perennial— sea ice has continued to decline. “Perennial ice can be very thick and very tough, but there’s much less of it left,” says Walt Meier of the National Snow and Ice Data Center. “There’s much more seasonal ice, which is weaker and thinner.” It’s also especially vulnerable to the summer sun. The Arctic remains dark for all or part of each day throughout much of the winter. When the sun returns in the spring and a warming begins, the seasonal ice “is going to melt away,” Meier warns. So any winter gains in ice cover “are going to be quickly lost.” Arctic sea ice hit an all-time low in September 2007. The magenta line indicates the average September ice cover from 1979 to 2000. National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, CO Perennial ice used to cover 50 to 60 percent of the Arctic, according to data collected by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This year it covers less than 30 percent. “Since the mid 1980s, we’ve lost about a million square miles of perennial ice,” says Meier. “That’s about one and half times [the size of] the state of Alaska.” The very old, tough ice that’s been around for six years or more also has declined. Once making up more than 20 percent of the Arctic area in the mid- to late 1980s, it now covers just six percent of the region. Meier says that this is a record low for perennial ice in winter and a very sharp drop even from last winter. “There’s this fear,” he says, “that we’re going over a cliff, in a sense, with this perennial ice.” He says the planet could be heading towards a situation where there won’t be any perennial ice left in the near future. Only seasonal ice would exist, which means that the Arctic Ocean would be ice-free during the summer. The decline of Arctic sea ice “is an iconic signal of global warming,” Meier says. It’s something that really sticks out “as being clear cut and definitely due to global warming.” Real warming, real warning : Left: February distribution of ice by its age during normal Arctic conditions (1985-2000 average). Right: February 2008 Arctic ice age distribution. The ice in the Arctic is much younger than normal, with vast regions now covered by firstyear ice and much less area covered by multiyear ice. National Snow and Ice Data Center, courtesy S. Drobot, Univ. of Colorado, Boulder Most scientists believe people are largely responsible for the warming of Earth’s atmosphere throughout the past century. Their burning of fossil fuels—such as coal, oil, and gas—releases greenhouse gases that trap the sun’s heat. Until fairly recently, scientists debated whether Earth’s fever was likely to last only a few years or whether it could persist for decades—maybe even longer. Now the debate appears to be over. There is a scientific consensus, which means an agreement among the vast majority of researchers in the field, that global warming is not a temporary blip. The pattern of worldwide warming appears to signal a true and potentially very long-term change in climate. Indeed, global warming is “unequivocal,” the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stated last year in a convincing set of reports. Susan Solomon is a senior scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder, Colo., who led one of the IPCC working groups. Using the word “unequivocal” was important, she says. The data that the IPCC reviewed were so strong, she explains, that the words “very likely” just wouldn’t get the point across. There’s a greater than 99 percent chance that our planet has warmed, she says. So there really “just isn’t any doubt about it.” The IPCC reports describe possible dramatic and lasting impacts of global warming that may occur. But, cautions Solomon, the warming and impacts that we’ll see in the next century depend a lot on how much carbon dioxide we emit. Carbon dioxide, a pollutant emitted as fossil fuels burn, is a major greenhouse gas. How severely the climate changes and precisely when and where those changes occur remain uncertain. If humanity drastically reduced its emissions of greenhouse gases, such as carbondioxide emissions, we could reduce how high Earth’s surface temperatures climb, Solomon says. But if we don’t, she warns, by the end of the century Earth’s average temperature could climb somewhere between 2 and 6 degrees Celsius (3.6 to 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit). “And under those circumstances, a lot of things would change,” Solomon says. “We’d see more drought, more heat waves. We’d also, ironically, see more heavy rainfall. We’d see sea levels rise—and though there’s a lot of uncertainty in how much they’d rise, numbers like half a meter [about 20 inches] wouldn’t surprise me in 100 years.” Such projections about droughts and sea-level rise aren’t certain. They are simply “best guesses,” Meier observes. “They could be wrong,“ he says. In fact, he notes, “Many skeptics focus on the fact that things might not be quite as bad as projected.” On the other hand, he points out that the effects of Earth’s fever could prove much worse than scientists have anticipated, “which is what we’re already seeing in terms of the rate of ice melt.” No summer sea ice—soon? The Arctic has shown the most rapid rates of warming in recent years. Surface air temperatures there have warmed at roughly twice the global rate, according to the IPCC reports. Science has predicted that the first signs of global warming would show up first and most dramatically in the Arctic. “And that’s indeed what we’re seeing with the decline of Arctic sea ice,” says Meier. The IPCC reports have concluded that the Arctic Ocean could lose its summer sea ice by the latter part of the century. Meier cautions, however, that such estimates are based on computer models. Those models are not up to date. In fact, he says, we’re finding that changes are occurring “much, much faster than the models have projected. The way things are going it’s likely that we’ll have an ice-free Arctic Ocean in the summer within a couple of decades. It could be even sooner.” Indeed, some scientists have speculated summer sea ice could disappear by 2013—only five years from now. “That’s on the extreme pessimistic edge of the estimates,” Meier says, “but it’s not implausible any longer.” He thinks the complete disappearance of summer sea ice in the Arctic is probably unavoidable. The warming trend is just too strong and seems to be accelerating. “You don’t need just one cold summer or one cold winter to turn things around,” he explains. “It would take many, many cold years in a row to reverse things and get things back to the way they were in the 1980s. And that’s not very likely.” That’s especially true, he says, because people are still using fossil fuels—and spewing greenhouse gases—at high and growing rates. Though it may be too late to save the Arctic Ocean from experiencing ice-free summers, “it’s not too late to prevent the worst of the impacts of global warming,” Meier argues. “The sea ice is an early warning and we can heed that warning. There is hope and there are solutions.” http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20080423/Feature1.asp