Word document

advertisement

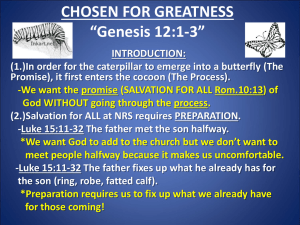

NOTES ON THE FIRST READINGS FOR THE TWELFTH WEEK OF ORDINARY TIME (Cycle 1) (if a festal day falls on any of these days, the readings of the feast are used instead) We now return to the book of Genesis and read the stories of the Patriarchs. The ‘pre-history’ of the Creation, Fall and Flood was read in Weeks 5 and 6 of this cycle. As we saw there, the book of Genesis is an amalgam of various traditions by various hands and editors, with two principal authors, one of the 9 th. century BC and one of the 8th., each using much older material. We also encounter the work of another hand, the so-called Priestly Writer (‘P’), who gave final shape to the text in the 6th. century BC, after the exile in Babylon; we will find one of his contributions in the course of this week. The early chapters of Genesis had set God’s good creation alongside the disobedience of his human creatures. We now see the continuance of his divine plan through those known as the Patriarchs, and, from the history of the nations in general (up to the Tower of Babel) we now concentrate on the history of Israel. God’s promises revolve around (a) a son, (b) many descendants and (c) the giving of the land, the ‘Promised Land’. For the other nations, the establishment of a dynasty and the possession of land are seen as being already in existence. For Israel, the Chosen People, things will be different: God’s wonderful goodness will be seen at work in an unpromising situation – Abraham and his wife Sarah are both childless and landless. One of the obvious questions is: is all this story historically true? It seems probable that the various authors have taken the development of a people over several centuries and compressed it all into three generations: Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Some believe that the Abraham, Isaac and Jacob stories are in fact the different traditions of different tribes, which have been fused together as a continuous story by means of genealogical links. The authors concentrate, in fact, on the theological truth: God is present with his people throughout time. The history of the Chosen People is one of continuity. Those living in the time of the Kings, for example, share a link with the earlier generations; indeed, many of the features of the age of the Kings, when the primary compilation of the book of Genesis took place, can be seen reflected back into the story of the Patriarchs itself. It is this sense of God’s abiding presence with his people which is the primary historical truth for the Genesis authors. Monday: Genesis 12: 1-9. Abram – the name change to Abraham comes in chapter 17 – moves with his father Terah from Ur (in Mesopotamia [Iraq]) towards the land of Canaan (which is to become the Promised Land), but settles in Haran. From Haran, Abram is now urged forward by God (not like the other nations, who after the Tower of Babel were scattered willy-nilly over the face of the earth). God’s blessing of Abram is so rich that people will in future use Abram as a yardstick by which to measure the blessings they themselves receive. Abram passes south through Shechem and Bethel (north of Jerusalem) and on into the Negeb on the way to Egypt. Altars are erected at the stopping-places as acknowledgment of God as the God of the land. Abram passes on into Egypt to stay there during a famine (thus mirroring the end of the Genesis story, where Jacob and his family will similarly arrive in Egypt). Tuesday: Genesis 13: 2, 5-18. The division of the land between Abram and his nephew Lot. Lot should have deferred to his uncle, but Abram generously gives him first choice. Lot chooses the fertile Jordan plain (this choice will rebound on him, as we will see). As a result, God reaffirms his own promise to Abram, even while the land is occupied by the Canaanites. Abram (unlike Lot) only looks upon the land when God tells him to. Abram arrives at Hebron, the future heartland of David’s ancestry. Wednesday: Genesis 15: 1-12, 17-18. Abram has no son, but God still reassures him that his descendants will be like the stars (this reflects the divine promise to David [Psalm 88: 2-5] that the Lord’s covenant is as firmly established as the heavens). God assures Abram of his possession of the land by means of a covenant oath. The practice of making such an oath by cutting animals in two and having both parties walk between is attested in Jeremiah 34: 18. Here it is God himself who passes between the two halves. The extent of the land promised to Abram is in fact the fullest extent of the land in the time of King David (from the Brook of Egypt to the River Euphrates in the East). Thursday: Genesis 16: 1-12, 15-16. When he left Haran, Abram was 75; now he is 86 and still there is no son. His wife Sarah therefore allows him (as custom permitted) to have a child by their slave-woman, Hagar. When Hagar becomes pregnant, Sarah naturally suffers from a loss of self-esteem. She ill-treats Hagar who tries to flee back to her native Egypt. God, however, offers Hagar his protection; her son, Ishmael (=May God heed), though a wild and troublesome man, will himself be a leader of many. Friday: Genesis 17: 1, 9-10, 15-22. We move forward 13 years. God again addresses Abram. This section comes from the later ‘Priestly Writer’, one of whose hallmarks is to refer to God by the title used here: El Shaddai = God of the Mountain. Abram’s name is changed to Abraham (not in our extract): Abram = Exalted Father, Abraham = Father of Many. The wife’s name change (Sarai to Sarah) is one of dialect. The mark of circumcision: in Israel this was a later practice, but the Priestly author moves it back to Abraham’s time, so as to give the Israelites of his own generation the sense of sharing inn the experience of their founder. Abraham laughs when God says he will still have a son; Abraham proposes the strapping young Ishmael as the recipient of God’s blessings. God says that Ishmael will have his own descendants (listed in Genesis 25: 12-18), but that Abraham will have his own son, Isaac (=he laughs/she laughs/ or [possibly] God laughs in delight]. Saturday: Genesis 18: 1-15. The divine visit to Abraham at the Oak of Mamre. The divine presence is represented now by one, now by three men; the divine fullness cannot be grasped by humans. The next three stages of the story are all linked: God’s visit to Abraham, Abraham’s questioning of God about his impending destruction of Sodom, God’s moving on to destroy Sodom. Abraham is dozing in the heat, but has to scamper about in order to prepare for the hospitality meal. The divine visitor says almost nothing. Then, when the meal is over, the divine visitor takes the initiative. Sarah laughs at the promise of a son, just has her husband had done. The divine visitor rebukes her for trying to deny that she had laughed.