Growth and its Gendered Implications in India

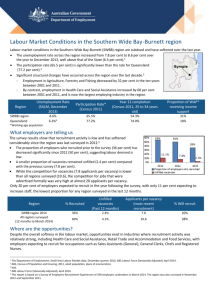

advertisement