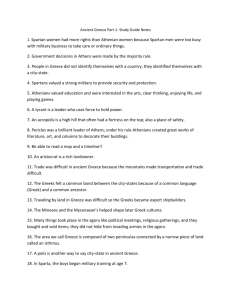

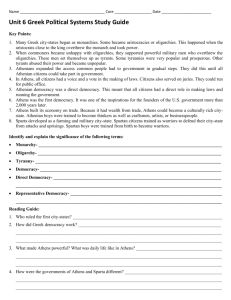

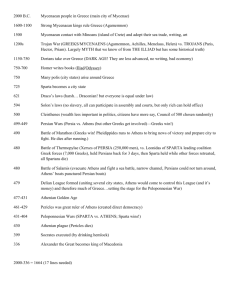

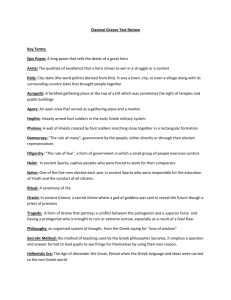

Overview of Archaic & Classical Greek History

advertisement