PETROLOGY LAB 4: Sedimentary Rocks – Textures and Structures

advertisement

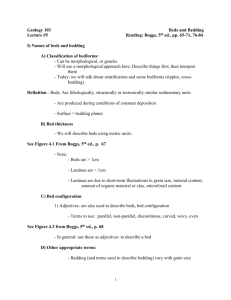

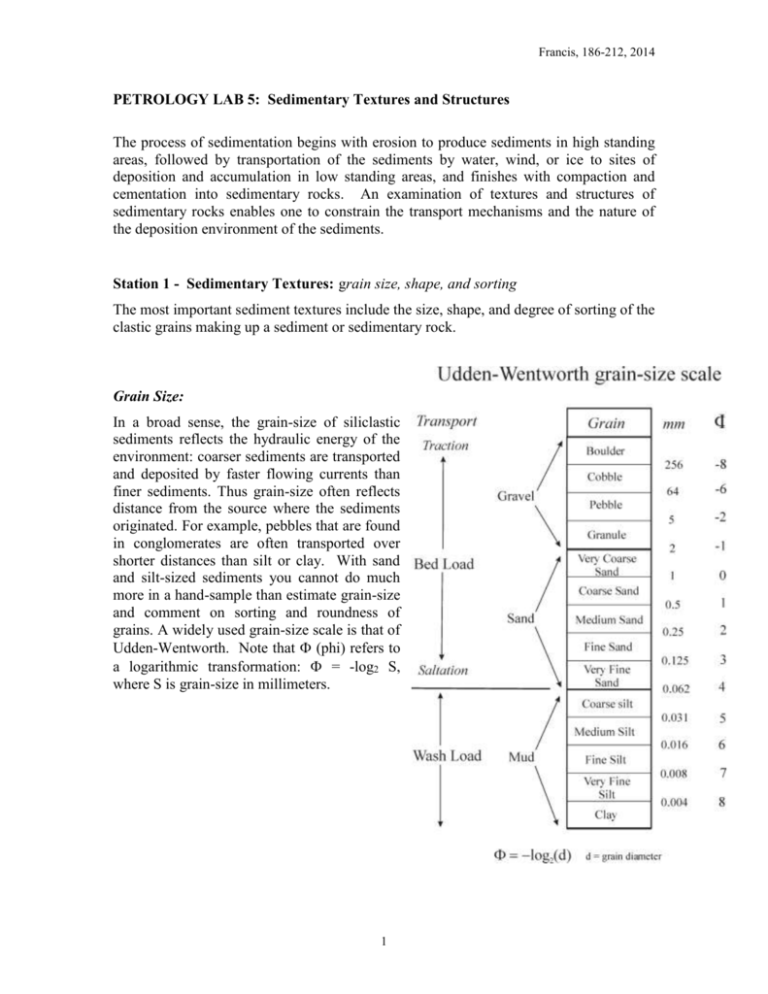

Francis, 186-212, 2014 PETROLOGY LAB 5: Sedimentary Textures and Structures The process of sedimentation begins with erosion to produce sediments in high standing areas, followed by transportation of the sediments by water, wind, or ice to sites of deposition and accumulation in low standing areas, and finishes with compaction and cementation into sedimentary rocks. An examination of textures and structures of sedimentary rocks enables one to constrain the transport mechanisms and the nature of the deposition environment of the sediments. Station 1 - Sedimentary Textures: grain size, shape, and sorting The most important sediment textures include the size, shape, and degree of sorting of the clastic grains making up a sediment or sedimentary rock. Grain Size: In a broad sense, the grain-size of siliclastic sediments reflects the hydraulic energy of the environment: coarser sediments are transported and deposited by faster flowing currents than finer sediments. Thus grain-size often reflects distance from the source where the sediments originated. For example, pebbles that are found in conglomerates are often transported over shorter distances than silt or clay. With sand and silt-sized sediments you cannot do much more in a hand-sample than estimate grain-size and comment on sorting and roundness of grains. A widely used grain-size scale is that of Udden-Wentworth. Note that (phi) refers to a logarithmic transformation: = -log2 S, where S is grain-size in millimeters. 1 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Sorting and Roundness: The degree of sorting of a sandstone reflects the transportation mechanism and the nature of the depositional environment, and increases with increasing agitation and reworking experienced. For example, aeolian and beach sandstones typically are well sorted, contain well rounded grains and no matrix (they are said to be ‘texturally mature’), whereas fluviatile sandstones are moderately to poorly sorted and may contain angular grains and matrix (they are said to be ‘texturally immature’). Conglomerates and breccias can be distinguished by the roundness versus angularity of the clasts in the rock: if the clasts are rounded the rock is referred to as a conglomerate, if they are angular it is a breccia. A conglomerate or breccia can be either: monomictic - the clasts are all the same type of rock. polymictic – there are different types of rock clasts. It is also important to note the ‘maximum clast size’, since it is often a reflection of the hydraulic energy of the transporting current. In addition you should examine the clast-matrix relationships in these samples: clast-support fabric is typical of fluvial and beach gravel. matrix-support fabric is typical of debris flows and glacial tills. 2 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Colour: Color can give useful information on lithology, depositional environment, and diagenesis. Two factors determine the color of many sedimentary rocks: the oxidation state of iron and the content of organic matter. Iron exists in two oxidation states: ferric (Fe3+) and ferrous (Fe2+). Where ferric iron is present it frequently occurs as the mineral hematite and even in concentrations of less than 1% this imparts a red color to the rock. Where the hydrated forms of ferric oxide (goethite and limonite) are present the sediment has a yellow-brown color. The formation of hematite requires oxidizing conditions and these are frequently present within sediments of semi-arid and continental sub-aerial environments. Sandstones and mudrocks of these environments (e.g., desert, lakes and rivers) are frequently reddened through hematite pigmentation and such rocks are referred to as ‘red beds’. Many red marine sediments are, however, also known. Where reducing conditions prevailed within a sediment the iron is present in the ferrous state and is contained in clay minerals, imparting a green color to the rock. Organic matter within a sediment gives rise to grey colors and with increasing organic content the rock becomes black. Such organic-rich sediments generally form in anoxic conditions. Thus color may provide you with additional information about the depositional environments and should be included in your considerations when examining a sedimentary rock. For the samples in Station 1, estimate grain-size, sorting and roundness, look at the color and think about what conclusions you can draw about depositional environment and distance from the source rocks. 3 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Station 2 - Sedimentary Structures: Bedding Bedding and lamination: The characteristic feature of sedimentary rocks is the presence of stratification or bedding, typically produced by changes in the pattern of sedimentation, such as changes in sediment composition and/or grain size. Bedding is generally defined as layering thicker than 1 cm, whereas finer scale layering is termed lamination. Lamination is commonly an internal structure of a bed and arises from changes in grain size between laminae, size-grading, or changes in composition between laminae. Each laminae may be the result of a single depositional event. Which of the specimens from this station show bedding and which lamination? What do these features indicate for the depositional environment in which the specimens were formed? Graded Bedding: Grading is a gradual change in grain-size upwards through a bed and typically develops in response to change in flow velocity during a sedimentation event. Beds with coarser grain-size at the bottom and fining towards the top are termed normally graded, while beds that show coarser grain-size at the top and finer grain-size at the bottom are termed reverse graded. Normal graded bedding is by far the most common, and can be an excellent tops indicator. Reverse graded bedding is relatively rare, and tends to occur in poorly sorted sediments that have been deposited rapidly from sediment-charged flows. Examine the specimens at this station from the point of view of whether they exhibit normal grading or inverse grading? How did the flow conditions change during sedimentation? 4 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Station 3 – Sedimentary Structures: Bedforms, and Cross Stratification: Cross stratification due to current ripples and dunes The nature of the bottom surface in terms of the sedimentary structures or bedforms, like ripples and dunes, is dependent on the current flow conditions. Bedforms are characterized by their wavelength and/or height as ripples (=0.05-0.2 m), dunes (=0.510 m), and sand waves (=5-100 m). In aqueous flows, for a given grain size and water depth ripples form at the lowest current velocity, followed by dunes, plane beds, and antidunes with increasing current velocity. Ripples and dunes are asymmetrical bedforms, which gradually move downstream as sediment is transported through erosion of the upstream-facing side and deposition over the bedform crest in foreset beds on the downstream-facing side. They are common in rivers, tidal flats, delta channels, on shallow-marine shelves, and on the deep-sea floor. The foreset beds of ripples and dunes are commonly preserved as cross stratification. These range from planar cross strata formed through the migration of straight crested ripples to trough cross strata formed through the migration of lunate or sinuous ripples. In planar cross bedding, the foresets (sloping beds) dip at angles up to 30 or more, and may have an angular basal contact with the horizontal. Trough cross bedding consists of scoop-shaped beds with tangential bases and dips of 20-30. The asymmetry of trough cross-bedding, and their cross cutting relationships, give excellent top and current direction indicators. The scale of the cross stratification reflects the bed form that they preserve: cross-bedding typically represents the preserved foreset beds of sand waves and dunes. cross lamination typically represents the preserved foreset beds of ripples Climbing Ripples: Under conditions of rapid deposition, successive ripples may climb onto the backs of previous ripples with little or no erosion, producing a ‘false’ cross bedding. Can you identify upstream-facing side and downstream-facing side in the specimens at this station? What can you say about the wavelength of the ripples? Can you determine the flow direction? 5 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Station 4 – Sedimentary Structures: Sole Markings and other structures: Sole Markings: The bottoms of sandy beds often have markings that are indicative of current flow and/or differential compaction: Grove casts Elogated ridges that represent filled depressions in the underlying bed. Commonly elongated parallel to the current direction, although it is typically not possible to tell the upstream ends from the downstream ends. Flute clasts: Bulbous ridges that are steeper in the upstream direction and flare downstream. They represent filled scour depressions in the underlying bed formed by eddies in the flow that deposited the overlying sands. Bounce, Prod and skip marks: Casts of small gouge marks in the underlying bed produced by the collision of fragments being carried by the flow that deposited the overlying bed. They commonly give the opposite sense of flute casts, that is their steep sides are downstream and their shallow sides up stream. 6 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Load casts: Ball, pillow, and bulge shaped sand structures that have sunk down into an underlying clay bed because of liquifaction and de-watering of the clays following the loading of the overlying sand bed. Similar to flutes, but more irregular, and they do not have any current direction implications. Not strictly a cast because they do not fill a pre-existing hole. 7 Francis, 186-212, 2014 De-watering Structures: Sandy sediments that are deposited very rapidly commonly have a significant proportion of trapped water that is expelled as the sediment undergoes compaction. This leads to the formation of dish and pillar structures. Dish structures are defined by dark coloured clay-rich laminations that appear saucer or dish shaped. They are associated with vertical pillar structures that are also defined by darker clay-rich material. Flame Structures: Sandy beds deposited by strong currents over clayrich beds commonly develop flames of the clay-rich material that have been dragged into the overlying sand. The asymmetry of flame structures can be used to determine the paleo-current direction. 8 Francis, 186-212, 2014 Fossils, rain spots, mud cracks, and other peculiar features: The samples at this station have interesting textures and structures that are easily recognized: Rain spots are small depressions with rims, formed through the impact of rain on the soft exposed surface of fine-grained sediments. Mud cracks are polygonal patterns on the bedding surface that formed through shrinkage and cracking of the bed or lamina. 9