Clinical Handbook - USC Dana and David Dornsife College of

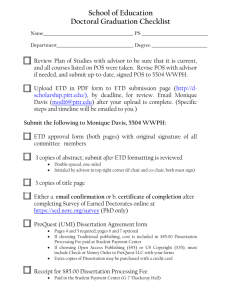

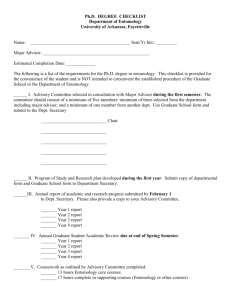

advertisement