UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

advertisement

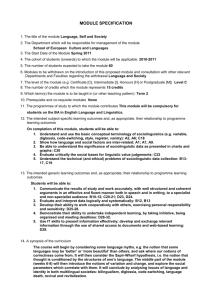

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures Course Number: Title: Units: Semester: Time: Professor: Office: Office hours: e-mail: homepage: EALC 374 Language and Society in East Asia 4 Fall 2007 Tue and Thu, 12.30 – 1.50; VKC155 Andrew Simpson. GFS 301 Thursday 2.00-3.00, or by appointment andrew.simpson@usc.edu www.usc.edu/schools/college/ling/people/faculty COURSE DESCRIPTION This course presents current sociolinguistic theories and ideas relating to a broad range of topics linking language and society, and considers how such thinking can be both applied to and informed by a consideration of patterns found in East Asia. The course sets out to document and analyse the ways that language interacts with other forces shaping society principally in China (and Taiwan), Japan, and North and South Korea, and how variation within the area of East Asia is best characterized and compared with sociolinguistic developmental patterns described in the West and other parts of the world. Given the importance that language has, in many ways, for almost all aspects of culture and societal interaction and organization, the content of the course should be relevant for students with a wide range of other primary academic interests, e.g. undergraduates focusing on East Asian anthropology, politics, religion, philosophy, as well as language-learning, and also linguistics majors interested in a focused application of sociolinguistics to the area of East Asia. COURSE ASSIGNMENTS, EXAMS, AND GRADES There will be a two-hour mid-term exam (October 4th) and a three-hour final exam (December 18th), accounting for 25% and 45% of the final grade. One assignment on Language Planning (due October 2nd) and a written project (due December 4th) will make up a further 10% and 20% respectively. The subject matter of the project will be designed to fit with each student’s individual interests and linguistic skills following discussion with the teacher of the course (Example: Design and use of a questionnaire to interview multiple informants and create a profile of language use in different domains of life in a selected region/conurbation of East Asia). READING MATERIALS There are no textbooks that students must buy for this course. Readings will be made available from a wide range of sources. The reading list provides an extensive weekby-week indication of a set of relevant works which will be referred to during lectures. Students will be asked to read a guided selection of these readings. 1 Grading Scales For the assignment graded 10 points 9-10 = A 8 = A7 = B+ 6=B 5 = B4 = C+ For the project graded 20 points 19-20 = A 17-18 = A15-16 = B+ 13-14 = B 11-12 = B9-10 = C+ For the mid-term graded 25 points 22-25 = A 19-21 = A17-18 = B+ 15-16 = B 13-14 = B10-12 = C+ For the final graded 45 points 42-45 = A 38-41 = A34-37 = B+ 30-33 = B 25-29 = B21-24 = C+ STATEMENT ON ACADEMIC INTEGRITY USC seeks to maintain an optimal learning environment. General principles of academic honesty include the concept of respect for the intellectual property of others, the expectation that individual work will be submitted unless otherwise allowed by an instructor, and the obligations both to protect one’s own academic work from misuse by others as well as to avoid using another’s work as one’s own. All students are expected to understand and abide by these principles. Scampus, the Student Guidebook, contains the Student Code of Conduct in Section 11.00, while the sanctions are located in Appendix A: http://www.usc.edu/dept/publications/SCAMPUS/gov/ Students will be referred to the Office of Student Judicial Affairs and Community Standards for further review, should there be any suspicion of academic dishonesty. The Review process can be found at: http://www.usc.edu/student-affairs/SJACS/ STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES Any student requesting academic accommodations based on a disability is required to register with Disability Services and programs (DSP). A letter of verification for approved accommodations can be obtained from DSP. Please be sure the letter is delivered to me as early in the semester as possible. DSP is located in STU 301 and is open 8.30 a.m. to 5.30 p.m., Monday to Friday. The phone number for DSP is (213) 740-0776. 2 SYLLABUS AUGUST Session 1: Tue 28th and Thu 30th Languages, Dialects and Varieties: an introduction SEPTEMBER Session 2: Tue 4th National language and language planning: an introduction. Session 3: Thu 6th and Tue 11th National language and language planning in Japan. Session 4: Thu 13th and Tue 18th National language and language planning in the People’s Republic of China/PRC Session 5: Thu 20th and Tue 25th National language and language planning in North and South Korea Session 6: Thu 27th National language and language planning in Taiwan OCTOBER Session 7: Tue 2nd and Thu 4th Minority languages and language shift. (a) minorities in the PRC, (b) Ainu, Okinawan, and Koreans in Japan, (c) minority groups in Taiwan. Session 8: Tue 9th and Thu 11th Language planning and identity in Hong Kong and Singapore Session 9: Tue 16th The spread and status of English in Asia. Assignment on Language Planning due. Thu 18th Mid-term Exam Session 10: Tue 23th and Thu 25th Diglossia, code-mixing, and code-switching. Session 11a: Tue 30th Bilingualism and bilingual education I. NOVEMBER Session 11b: Thu 1st Bilingualism and bilingual education II. 3 Session 12: Tue 6th Language Change Session 13: Thu 8th and Tue 13th Language and Gender Session 14: Thu 15th, Tue 20th, Thu 22nd Language and Politeness: theory and contrastive patterns in Japan, Korea, and China Session 15: Tue 27th The ‘rest’ of East Asia: Southeast Asia I National and minority language issues in (a) Vietnam and Cambodia Thursday 29th Thanksgiving recess DECEMBER Session 16: Tue 4th and Thu 6th Southeast Asia II National and minority language issues in (a) Thailand and Laos, (b) Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines Mon 10th Written project due. Tue 18th Final Exam 4 LANGUAGE AND SOCIETY IN EAST ASIA READING LIST Session 1: Introduction: languages, dialects and varieties (1) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006) An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, chapter 2 ‘Languages, dialects and varieties’, (Oxford: Blackwell), 25-58. (2) Haugen, Einar. (2003), ‘Dialect, language, nation’, in C. Paulston and R.Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 411-23. Session 2: National languages and language planning (1) Nahir, Moshe. (2003), Language planning goals: a classification. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential reading (Oxford: Blackwell), 423-449. (2) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006) An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. (Oxford: Blackwell), chapter 15: Language Planning 356-382 (3) Holmes, Janet. (1992) An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. (London: Longman), chapter 4:79-89. (4) Kennedy, J. 1968. Asian nationalism in the 20th century. New York: Macmillan. (5) Tonnesson, Stein and Antlov, Hans. 1996. “Asian in theories of nationalism and national identity”. in Asian forms of the nation. Curzon: London 1-41. Session 3: National language in Japan (1) Gottlieb, Nanette. (2007), ‘Japan’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press).1 (2) Gottlieb, Nanette. (2005), Language and society in Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Chapters: 1 The Japanese language, 1-17; 3 Language and national identity: evolving views, 39-54; 4 Language and identity: the policy approach 55-77. (3) Loveday, Leo. (1986), Explorations in Japanese Sociolinguistics Amsterdam: John Benjamins), chapter 1: Japanese sociolinguistics with special reference to western research. 1-33. [overview of standard and regional varieties; gender, age, group identity markers; language planning; contact with other languages; Japanesebased pidgins; Japanese overseas communities;] (4) Kunhiro, Tetsuya, Inoue, Fumio, & Long, Daniel. (1999), Takesi Sibata. Sociolinguistics in Japanese Contexts (Berlin: Mouton), chapter 10: The rise and fall of dialects. [discussion of Standard Language and the creation of the ‘National Language’ in the Meiji era 183-190; the Dialect Eradication Movement 191-196; the advent of the age of the Common Language and the fate of dialects 196-206;] (5) Gottlieb, Nanette. (2001), ‘Language planning and policy in Japan’, in P. Chen and N. Gottlieb (eds.) Language Planning and Language Policy: East Asian perspectives (London: Curzon), 21-48. (6) Shibatani, Masayoshi. (1990), The Languages of Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), chapter 9: Dialects, 185-213. (7) Gottlieb, Nanette. (2005), Language and society in Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Chapter 5: Writing and reading in Japan, 78-99. (8) Carroll, Tessa. 2001. Language Planning and Language Change in Japan. 1 Note that this volume is currently in press and will appear in June 2007. Once the volume has been published, page numbers will be added to the many chapters from this volume which will be used for this course. 5 1. Language planning: definitions and frameworks. 2. Historical background and parallels. 3. [12] State of the language, state of the nation (language decay). 4. Language, state and citizens. 5. Speech and writing in the modern age (computers, internet). 6. National and regional identities in flux. (9) Shibatani, Masayoshi. “Dialects” chapter 9 of Language in Japan. (10) Nish, Ian. “Nationalism in Japan.” (11) Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “The frontiers of Japanese identity.” (12) Yasuda, Maki. 2005. “Writing and standard language – the development of modern Japanese”. Paper, University of London. Session 4: National language in China (1) Chen, Ping. (2001), ‘Development and Standardization of Lexicon in Modern Standard Chinese’, in P. Chen and N. Gottlieb (eds.) Language Planning and Language Policy: East Asian perspectives (London: Curzon), 49-73. (2) Chen, Ping. (2007), ‘China’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (3) Rohsenow, John. (2001), The present status of digraphia in China. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 150: 125-40. (4) Dreyer, June. (2003), ‘The evolution of language policies in China’ in Michael Brown and Sumit Ganguly. (2003), Fighting Words (Boston: MIT Press), 353-384. (5) Loden, Torbjorn. “Nationalism transcending the state: changing conceptions of Chinese identity. (6) Chen, Ping. Modern Chinese: history and sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. (7) Norman, Jerry. Chinese. Cambridge University Press. [Dialects] (8) Lester, Richard. 2005. “The establishment and promotion of a common spoken language for China in the 20th century.” Session 5: National language in North and South Korea (1) Yeon, Jaehoon (2000), ‘Standard language’ and ‘cultured language’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 31-43. (2) Song, Jae Jung. (2002), The Korean Language (London: Routledge), chapter 7: North and South Korea, 163-175. (3) Lee, Iksop & Ramsey, Robert. (2000), The Korean Language (Albany: State University of New York Press), chapter 1: The modern dialects, 307-14. (4) King, Ross. (2007), ‘North and South Korea’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (5) Ramsey, Robert. (2000), ‘The invention and use of the Korean alphabet’, in Homin Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 22-40. (6) King, Ross. (2000), ‘Dialectal variation in Korean’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.), Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 264-280. (7) King, Ross. (2007), ‘North and South Korea’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press), [sections on historical use of Chinese for writing vs. use of Korean for speech]. (8) Lee, Hyun-Bok. 1990. “Differences in language use between North and South Korea. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 82: 71-86. (9) Kumatani, Akiyasu. 1990. “Language policies in North Korea. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 82: 87-108. 6 (10) King, Ross. “Nationalism and Language Reform in Korea: the Questione della Lingua in precolonial Korea. (11) King, Ross. “Language, politics, and ideology in the postwar Koreas.” (12) Hong, Yunsook. A sociolinguistic study of Seoul Korean. Section on Language divergence between North and South Korea. (13) Sohn, Ho-min. The Korean language. Cambridge University Press. Chapters on origins, historic development, writing, dialects. (14) Shinn, Hae Kyong. 1990. “A survey of sociolinguistic studies in Korea”. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 82: 7-23. Session 6: Taiwan (1) Simpson, Andrew. (2007), ‘Taiwan’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (2) Dreyer, June. (2003), ‘The evolution of language policies and national identity in Taiwan’, in Michael Brown and Sumit Ganguly. (2003), Fighting Words (Boston: MIT Press), 385-411. (3) Chen, Ping. (2000), Modern Chinese (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [section on the writing of non-Mandarin Chinese dialects: Cantonese, Taiwanese] (4) van den Berg. “Taiwan’s sociolinguistic setting.” (5) Huang, Shuanfan. 2000. “Language, identity and conflict: a Taiwanese study.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 143: 139-149. (6) Tse, John Kwock-ping. 2000. “Language and a rising new identity in Taiwan”. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 143: 151-64. (7) Hughes, Christopher. “Post-nationalist Taiwan”. Session 7: Minorities (1) MacSwann, Jeff, and Rolstad, Kellie. (2003), Linguistic diversity, schooling, and social class: rethinking our conception of language proficiency in language minority education. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 329-41. (2) Paulston, Christina. (2003), Linguistic minorities and language policies. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 394-407. (3) Paulston, Christina. (2003), Language policies and language rights. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 472-83. (4) Holmes, Janet. (1992) An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. (London: Longman), chapter 3. (5) Gottlieb, Nanette. (2005), Language and society in Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) Chapters 2: Language diversity in Japan, 18-38; 6 Representation and identity: discriminatory language, 100-119. (6) Zhou, Minglang. (2000), Language attitudes of two contrasting ethnic minority nationalities in China, the ‘model’ Koreans and the ‘rebellious’ Tibetans. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 146:1-20. (7) Shibatani, Masayoshi. (1990), The Languages of Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), chapter 1: the Ainu Language, 3-10 (8) Dreyer, June. (2003), ‘The evolution of language policies in China’ in Michael Brown and Sumit Ganguly. (2003), Fighting Words (Boston: MIT Press), 353-384. 7 (9) Shibatani, Masayoshi. “The Ainu language.” The Languages of Japan. Cambridge University Press. (10) Brown, Michael. “Language policy and ethnic relations in Asia.” In Fighting Words (Boston: MIT Press). (11) Davies, Kathryn. 2002. “The status of the Korean language in Japan from 1945 until the present day.” Paper, University of London. Session 8: Hong Kong and Singapore (1) Simpson, Andrew. (2007), ‘Hong Kong’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (2) Simpson, Andrew. (2007), ‘Singapore’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Session 9: English in Asia (1) Crystal, David. (1997), English as a Global Language (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). (2) Saino, Hirokazu. “A sociolinguistic study of the English language in Japan.” Paper, University of London. (3) Maeo, Keiko. “The problems of English education in Japan.” Paper, University of London. Session 10: Diglossia, code-mixing and code-switching (1) Kozasa, Tomoko. (1998), Code-switching in Japanese/English: a study of Japanese-American WWII veterans. Japanese/Korean Linguistics 10 209-222. (2) Ferguson, Charles. (2003), Diglossia. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 345-59. (3) Loveday, Leo. (1996), Language contact in Japan: a socio-linguistic history. (Oxford: Clarendon Press). Chapter 5: Japanizing and westernizing patterns 114-156 (including code-switching and code-mixing 124-137). (4) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (Oxford: Blackwell), chapter 4: Diglossia, Code-switching, Bilingualism, Multilingualism, 88118. (5) Holmes, Janet. (1992) An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. (London: Longman), chapter 2. (6) Li Wei, Milroy, Leslie, and Ching, Pong Sin. (2000), A two-step sociolinguistic analysis of code-switching and language choice: the example of a bilingual Chinese community in Britain. In Li Wei (ed.) The Bilingual Reader (Oxford: Blackwell), 188-211. (7) Nishimura, Miwa. (1997) Japanese/English Code-switching (New York: Peter Lang). (8) Shih, Yu-hwei and Mei-hui Sung. “Code-mixing of Taiwanese in Mandarin newspaper headlines: a socio-pragmatic perspective.” (9) Shih, Yu-hwei and Jennifer M. Wei. “Code-switching in Taiwanese.” (10) Kubler, Cornelius. “Code-switching between Taiwanese and Mandarin in Taiwan”. (11) Shih, Yu-hwei. “To –er is to Err: a case of code-switching in standard Mandarin.” (12) Young, Russell, and Myluoung Tran. 1999. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 140: 77-82. 8 (13) Loveday, Leo. “Japanizing and westernizing patterns.” [word-creation] in Natsuko Tsujimura (ed.) Japanese Linguistics (London: Routledge). Session 11: Bilingualism and bilingual education (1) Lambert, Wallace. (2003), A social psychology of bilingualism. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 305-21. (2) Tucker, Richard. (2003), A global perspective on bilingualism and bilingual education. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 464-72. (3) Byun, Myung Sup. (1990), Bilingualism and bilingual education: the case of Korean immigrants in the United States. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 82: 109-28. (4) Noguchi, Mary & Fotos, Sandra (eds.) (2001), Studies in Japanese Bilingualism (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters). (5) Raschka, Christine, Wei, Li, and Lee, Sherman. (2002), ‘Bilingual development and social networks of British-born Chinese children’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language 153:9-25. (6) Lo Bianco, Joseph (ed.) Language Policy. Special Issue on the teaching of Chinese. (7) Goebel Noguchi, Mary and Sandra Fotos. 2001. Studies in Japanese bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Book review in International Journal of the Sociology of Language 152: 179-184. (8) Feng, Anwei. 2007. Bilingual education in China. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Session 12: Language change (1) Sohn, Ho-min. (2000), ‘Korean in contact with Chinese’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 44-56. (2) Ramsey, Robert. (2000), ‘Korean in contact with Japanese’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 57-63. (3) Loveday, Leo. (1996), Language contact in Japan: a socio-linguistic history. (Oxford: Clarendon Press). Chapters: 2. The Chinese heritage and contact with other Asian languages, 26-42, 43-46; 3. The social evolution of Japanese contact with European languages, 47-76; 4. The contexts of contemporary contact, 77-99: 6. The social reception of contact with English now 157-188; 7. The functions of language contact in Japan today, 189-211; (4) Hibiya, Junko. (2005), ‘The velar nasal in Tokyo Japanese: a case of diffusion from above’, in Natsuko Tsujimura (ed.) Japanese Linguistics (London: Routledge), 1-14. (5) Yoneda, Masato. (2001), ‘Survey of standardization in Tsuroka, Japan: comparison of results from three surveys conducted at 20 year intervals’, Nihongo gagaku [Japanese Linguistics]. (6) Long, Daniel. (1996), ‘Quasi-standard as a linguistic concept’, American Speech 71:2:118-135: University of Alabama Press. (7) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (Oxford: Blackwell), chapter 8: Language Change, 191-218. (8) Chen, Ping. (2000), Modern Chinese (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), chapters on change from classical, written Chinese (wen-yan) to colloquial, written Chinese (bai-hua). 9 (9) Aitchison, Jean. (2001), Language Change: progress or decay? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). (10) Litosseliti, Lia. 2006. Gender and language: theory and practice. London: Hodder Arnold. Session 13: Language and Gender (1) Reynolds, Katsue Akiba. (2000) Female speakers of Japanese in transition. In Sally Coates (ed.) Language and Gender (Oxford: Blackwell), 299-308, and S. Ide and N. McGloin (eds.) (1991) Aspects of Japanese Women’s Language (Tokyo: Kuruosio Publishers), 129-46. (2) Tannen, Deborah. (2003), The relativity of linguistic strategies: rethinking power and solidarity in gender dominance. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 208-229. (3) Cook, Haruko Minegishi. (1989), Functions of the filler ano in Japanese. Japanese/Korean Linguistics 11 19-38. (4) Cho, Young. (2000), ‘Gender differences in Korean speech’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 189-198. (5) Takano, Shoji. (2000), ‘The myth of a homogeneous speech community: a sociolinguistic study of the speech of Japanese women in diverse gender roles’, International Journal of the Sociology of Language 146: 43-85. (6) Shibamoto, J. (2005), ‘Women’s speech in Japan’, in Natsuko Tsujimura (ed.) Japanese Linguistics (London: Routledge), 181-221. Also in J. Shibamoto (1985), Japanese women’s Language (New York: Academic Press), 29-67. (7) McGloin, Naomi Hanaoka. (2005), ‘Sex difference and sentence-final particles’, in Natsuko Tsujimura (ed.) Japanese Linguistics (London: Routledge), 222-238. (8) Loveday, Leo. (1986), Explorations in Japanese Sociolinguistics (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), chapter 2: Pitch, politeness and sexual role: an experiment on the occurrence of pitch in Japanese and its results, 80-97. (9) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (Oxford: Blackwell), chapter 13: Gender, 315-335. (10) Holmes, Janet (1992) An introduction to sociolinguistics (London: Longman), chapters 7 & 12. (11) Trudgill, Peter. (1974), Sociolinguistics (London: Penguin), chapter 4. (12) Graddol, David & Swann, Joan. (1989), Gender voices (Oxford: Oxford University Press), chapters 4 & 5. (13) Holmes, Janet. (1998), ‘Women’s talk: the question of sociolinguistic universals’, in Jennifer Coates (ed.) Language and Gender (Oxford: Blackwell). (14) Cho, Young. (2000), ‘Gender differences in Korean politeness strategies’, in Homin Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 199-211. (15) Ide, Sachiko and Yoshida, Megumi. (2000), ‘Sociolinguistics: honorifics and gender differences’, in Naoki Fukui (ed.) Handbook of Japanese Linguistics (Oxford: Blackwell), 444-80. (16) Language, gender and ideology in Japan. Collected essays on language and gender in modern Japan. (17) Kii, Hiroe. 2001. “Gender and politeness in Japanese.” Paper, University of London. (18) Okamoto, Shigeko and Janet Shibamoto Smith. 2004. Japanese Language, Gender and Ideology. Oxford University Press. 10 Session 14: Politeness (1) Okamoto, Shigeko. (2000), The use and non-use of honorifics on sales talk in Kyoto and Osaka: are they rude or friendly? Japanese/Korean Linguistics 12 141-57. (2) Brown, Roger and Gilman, Albert. (2003), Pronouns of power and solidarity. In Christina Bratt Paulston and Richard Tucker (eds.) Sociolinguistics: the essential readings (Oxford: Blackwell), 156-76. (3) Hwang, Juck-Ryoon. (1990), ‘Deference’ versus ‘politeness’ in Korean speech. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 82:41-55. (4) Pan, Yuling. (2000), Politeness in Chinese face-to-face interaction (Stamford: Ablex). (i) How polite are the Chinese? 1-24 (ii ‘Do I know you?’ Inside and outside behavior relations in politeness behavior 25-52 (iii) ‘You are my friend’ building of connection in an official setting 53-76 (iv) ‘Who is the boss?’ Hierarchical structure in an official setting 77-104 (v) Conflicting factors in a family setting 105-142 (vi) ‘What really is Chinese politeness?’ a situation-based approach to politeness 143-155. (5) King, Ross. (2000), ‘Korean kinship terminology’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 101-17. (6) Choo, Miho. (2000), ‘The structure and use of Korean honorifics’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 132-145. (7) Koh, Haejin. (2000), ‘Usage of Korean address and reference terms’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 146-154. (8) Park, Yong-yae. (2000), ‘Politeness in conversation in Korean: the use of –nunde’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 16473. (9) Bynon, Andrew. (2000), ‘Korean cultural values in request behaviors’, in Ho-min Sohn (ed.) Korean Language in Culture and Society (Hawaii: Klear), 174-88. (10) Wardhaugh, Ronald. (2006), An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (Oxford: Blackwell), chapter 11: Solidarity and Politeness, 260-283. (11) Brown, Penelope & Levinson, Steven. (1987), Politeness: some universals in language usage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). (12) Loveday, Leo. (2005), ‘Speaking of giving: the pragmatics of Japanese donatory verbs’, in Natsuko Tsujimura (ed.) Japanese Linguistics (London: Routledge), 15-38. (13) Kunhiro, Tetsuya, Inoue, Fumio, & Long, Daniel. (1999), Takesi Sibata. Sociolinguistics in Japanese Contexts (Berlin: Mouton), chapter 6: The honorific prefix –o in contemporary Japanese, 99-125. (14) Park Mun, Mae-Ran. (1991), Social variation and change in honorific usage among Korean adults in an urban setting. PhD dissertation University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. (15) Matsumoto, Yoshiko. (1992), ‘Linguistic politeness and cultural style: observations from Japanese’, Japanese/Korean Linguistics 3: 55-67. (16) Usami, Mayumi. (1999), Discourse Politeness in Japanese Conversation: some implications for a universal theory of politeness (Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo). (17) Yu, Kyong-ae. “Are the notions of face and face-saving strategies universal?” Paper, Chung-Ang University. (18) Kobayashi, Hiromi. 2001. “Politeness in Japanese and the importance of distance and status in Japanese society.” Paper, University of London. 11 Session 15: Southeast Asia I: Vietnam, Cambodia (1) O’Harrow, Steve & Le, Minh-hang. (2007), ‘Vietnam’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (2) Heder, Steve. (2007), ‘Cambodia’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Session 16: Thailand, Laos, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines (1) Simpson, Andrew & Thammasien, Nualnoi. (2007), ‘Thailand and Laos’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (2) Asmah Haji Omar. (2007), ‘Malaysia’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (3) Simpson, Andrew. (2007), ‘Indonesia’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (4) Gonzales, Andrew. (2007), ‘The Philippines’, in Andrew Simpson (ed.) Language and National Identity in Asia (Oxford: Oxford University Press). (5) “Chinese search for identity in southeast Asian: the last half century”. 12