Teaching Literature and Reading Performances: a possible

advertisement

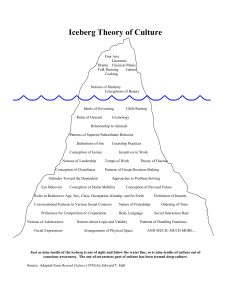

Teaching Literature and Reading Performances: a possible relation Associate Professor Gitte Holten Ingerslev Danish School of Education Aarhus University Denmark ghi@dpu.dk This article deals with the relations between different approaches to literature teaching and the resulting reading performance among Danish students in upper secondary school (16-19 year olds in the Danish Gymnasium). It looks into how the reading of literature can be both supported and hindered in literature lessons. In Denmark, the number of young people opting for upper secondary school has tripled over the last 20 years, resulting in a much wider range of student backgrounds in every class. In spite of this fact, teaching has not changed radically. It remains directed towards the small percentage of students who are already relatively experienced readers and rather sophisticated language users. The possible consequence is that non-reading readers experience defeat and subsequent lack of interest in language and literature. As a result, many students might be in danger of never establishing personal reading strategies or developing a joy of reading. The two studies which are the basis of the article aim at investigating the relation between the teacher’s conception1 of learning and knowledge on the one hand, and the student’s conceptions of learning, reading and interpreting literary texts, on the other (Marton, Dall'Alba et al. 1993; Boulton-Lewis, Smith et al. 2001). Teachers and students tend to be embedded in their individual cultural background, and they have attitudes and ways of acting which differ from person to person. These differences are not often made explicit, and it is one of the aims of this article to shed light into that area as a greater understanding of that field will lead to a more precise understanding of the difficulties which the student with little reading experience face in upper secondary school. Another aim of the article is to reveal possible connections between students’ learning conceptions and learning approaches, and their reading and interpretation skills. Finally the 1 Conceptions and ways of understanding are not seen as individual qualities. Conceptions of reality are considered rather as categories of description to be used in facilitating the grasp of concrete cases of human functioning. Since the same categories of description appear in 'different situations, the set of categories is thus stable and generalizable between the situations even if individuals move from one category to another on different occasions. The totality of such categories of description denotes a kind of collective intellect, an evolutionary tool in continual development. (Marton 1981) 1 article describes possible ways of teaching reading and writing and at the same time supporting the students in developing metacognitive skills. Teachers and students in literature classrooms Often the teachers´ theoretical backgrounds for choosing literary texts and their criteria for selection of reading approaches are not explicit. Neither are the teachers’ conceptions of good reading competences, of a good text and of a student’s appropriate basic knowledge. By conception of knowledge is meant whether knowledge is an objectively given truth which the teacher wants to convey to the students, or whether knowledge is being constructed in each individual brain through working with the material. That leads to the fundamental ontological question of whether the text exists before the reading, or whether it comes to life through being read. An answer to that question is decisive to the way a text will be taught. And it leads to an epistemological question: How does a person learn, and how does a person read? The answers to these questions may vary, and the different approaches may lead to clashes in the classroom. Such a situation is illustrated in Diagram 1: The teacher’s conception of knowledge The teacher’s view of the subject The student’s conception of learning and study behaviour The teacher’s teaching practise The teacher’s idea of the ideal educational setting The student’s way of reading and learning The student’s idea of the content and aim of the subject The student’s idea of the ideal educational setting Diagram 1. Hidden clashes in the classroom The teacher’s conception of knowledge, view of the subject, and idea of the ideal educational setting is decisive for the teacher’s teaching practice and is often not expressed openly in the classroom. This means that (some of) the students are not able to decode what is required. 2 On the other hand the students in a classroom have conceptions of learning and ideas of the ideal educational setting which are decisive for their study behaviour, and they have an idea of the subject content and of the aim of the subject which form the basis of their ways of reading and learning. For these reasons, among others, students assume different roles in classrooms. In the PEEL project (Baird and Mitchell 1987), they are categorized as follows: Passive Receptivity. In this case responsibility and control of the lesson is wholly the teacher’s. Student work is limited to undemanding roles such as giving superficial responses, transcribing work etc. Students do not fully understand the nature, purpose or progress of the lesson. They are uninformed and are not involved in managing the lesson and lesson content. Relatively uninformed responding is another way of describing students’ roles in class. Students participate actively, but mainly when directed, by answering teacher questions or performing set tasks. The teacher still has the control. Students do not fully understand the nature, purpose or progress of the lesson and there may be insufficient time, encouragement, or student inclination to ask and gain answers to many evaluative questions. Some students’ questions or answers are valued more than others by the teacher. Students might be active, but not fully informed and not involved in managing the lesson and lesson content. Informed participation. In this case students participate actively according to teacher directions. Teacher assumes responsibility and control for lesson nature and development. Students ask evaluative questions and are aware of, or actively engaged in finding out, answers. All contributions are valued by the teacher and, as far as possible, considered critically by the class. Students are active. They are informed, but not involved in managing the lesson and lesson content. Informed Collaboration. Students collaborate actively with the teacher and share responsibility and control of the nature, purpose, and progress of the lesson. Students ask evaluative questions, and reflect on and determine answers. All contributions are valued by the teacher and, as far as possible, considered critically by the class. Students are active, informed and involved in managing the lesson and lesson content. The article is based on two studies which investigate and map student reactions to different kinds of teacher instructions. The above mentioned categories are used in the final analysis. 3 Another related area which is subsequently being investigated is the conception of progression in connection with teacher instruction. The conception of progression is based on an idea of development towards a goal including increasingly more complex aspects. It is a movement from the simple to the complex through more and more advanced ways of learning so that learners develop the ability to look at themselves in relation to the text and in relation to their own historic time and the time in which the text is produced, and to look at a text on several levels. Progression can be seen as a combination of a whole series of elements, such as metacognitive awareness, deep learning2 (Biggs 1987), higher order thinking, reading skills and linguistic competence – written as well as oral. The two studies investigates the necessary basis of progression. The two studies Both studies are empirical studies. Study 1 was carried out with eight teachers and eight classes in year 9-12, altogether 172 15-18 year old students, and investigates the relation between the teachers´ conception of learning and knowledge within literature teaching in each specific class and the students’ conceptions of learning and of reading literary texts. Study 2 is a collaborative action research project in one of the 10th grade classes. In Study 1, the teachers were asked the questions mentioned below. The questionnaire was given after classroom observation and a short interview: - Within the reading of literature, which competences do you want the students to develop? - How do you define progression? - Which teaching approach will enhance students´ competences and progression? The Deep Processing Student is the student who goes into depth in her work, who ponders and who is not satisfied till she has comprehended the material. She will not give up before she has understood what a problem is all about. The knowledge structure of a student like that will typically be integrated. That means that new knowledge is connected to existing knowledge. In this group of students there will be a majority with a complex approach to learning. 2 4 This study is based on qualitative as well as quantitative research: Classroom observations were carried out in five classrooms in three lower secondary schools – year 9/10 (folkeskoler) and in five classrooms in two upper secondary schools – year 10/11-12 (gymnasier). Open interviews were carried out with three lower secondary school teachers, five upper secondary school teachers, and nine students who were followed for three years – and interviewed once a year. The students filled in a questionnaire with open questions on learning and reading in year 9/10 and finally in their second year of upper secondary school. They also filled in two forms: Reflections on Learning Inventory (RoLI) (Meyer 2000; Meyer and Boulton-Lewis 1997) and a Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Pintrich et al. 1991). The teachers also filled in a RoLI questionnaire and an Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI) (Prosser and Trigwell 1999). The qualitative research approach used in this study is derived from phenomenography3. All teachers and selected students participated in open-ended interviews, designed to promote reflection about teaching and learning. Phenomenographic data analysis produced categories of description within conceptions of teaching and learning and of the reading of literature. Two researchers went through the data and defined these categories independently. They also discussed the categories together in order to establish categorical clarity. The variation, or qualitatively different ways of experiencing the process, is presented in the words of the participants as they talk about the teaching of the subject, and as they talked about the learning in the subject, and the reading of literature 1) Study 2 takes up the challenges posed by Study 1 and deals with one teacher and one class in 10th grade, the first year of upper secondary school in Denmark. It is a collaborative action research project. The primary purpose of Study 2 was to find out to which extent students developed personal conceptions of learning and personal study behaviour, sophisticated knowledge of language, and advanced reading skills Furthermore the following specific aspects were pointed out as being important in the study. 3 awareness about genre (oral and written) Phenomenography is a phenomenological research approach used in educational research 5 written work such as writing to reflect, writing to communicate, fiction as well as non fiction ability to give response to other’s work, written as well as oral response, resulting in a growing awareness of the fact that working with other people’s texts make you alert and critical to your own texts higher order thinking and metacognitive awareness reading, in producing texts, in reflecting on and analyzing a selection of texts development of cultural competence understanding of oneself in a social and historic context Major results of Study 1 Table 1 illustrates the overall results for Study 1. It gives a general picture of the positions in which the participants placed themselves. It is built from the categorisation of student and teacher positions based on their conceptions of learning and teaching. STUDENT 1 Conception of good learning: Surface Approach (Reproduction) - get more knowledge - remember - use TEACHER 1 Conception of good teaching: - transfer knowledge train apprentices Transmissive approach Certainty orientated 2 Deep Approach (Reflection) - understand - change one’s knowledge - change as a person 2 - enhance understanding and conceptualization - enhance cognitive, metacognitive and knowledge based abilities Interpretive, dialogic approach Uncertainty orientated Table 1. A diagram of teacher/student interaction 6 The results in the upper left quarter reveal a student with a limited conception of learning, one who is certainty orientated, which means that he or she feels threatened by teaching which challenges their thinking. Analyses of student interviews show that these students predominantly come from non-reading backgrounds. They tend to feel insecure and ill at ease when starting in upper secondary school, especially in humanistic, interpretive subjects compared to the more exact subjects. A student from this group would typically say: ‘Just write on the blackboard what I’m supposed to say at my exam’. A teacher in the upper right quarter sees a professional teacher as a person who is good at knowledge transmission, who is well prepared for every lesson and who leads the class through the material. A student in bottom left quarter is probing and investigative. He or she wants to understand the content of the subject and would typically want to do project based, decentralised work which would challenge habitual thinking and enhance individual development. A teacher in the bottom right quarter, beyond the specific subject, aims at his or her student’s personal development. He or she sees a dialogical approach as part of good teaching procedure and regards social processes as not only a way to learning and understanding but also a student’s possible way to understanding aspects of him- or herself. The diagram gives a general picture of the positions which the investigation showed that students and teachers take in relation to each other in classrooms, and the diagram is based on the categorisation of student and teacher positions based on their conceptions of learning and teaching. I will return to these positions and the results of the clashes between incompatible approaches later in the article. The teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning In the investigation in study 1 the 8 teachers’ conceptions of good teaching fall into these four categories: Good teaching is: 1) transmission of knowledge from teacher to student 2) development of abilities and understanding of the subject along the lines of - or in accordance with – the teacher’s abilities and understanding 3) teacher-student co-operation aiming at enhancing the student’s understanding and conceptualising 7 4) planning of teaching sessions where the students have the access to developing cognitive, metacognitive and domain specific abilities. The aim is broader than strictly domain specific. The teachers’ conceptions of good teaching were strongly connected to the teachers’ conceptions of learning listed below. The teachers who primarily focussed on content answered within categories 1. and 2. in Good Teaching (‘transmission of knowledge from teacher to student’ and ‘development of abilities and understanding of the subject along the lines of - or in accordance with - the teacher’s abilities and understanding’) The teachers who primarily focussed on competence, meaning and growth answered within categories 3. and 4. (‘teacher-student co-operation aiming at enhancing the student’s understanding and conceptualising’ and ‘planning of teaching sessions where the students have the access to developing cognitive, metacognitive and domain specific abilities’) The teachers conceptions of learning fall into these categories: Learning means: 1) to add to knowledge and to remember 2) Development of ability to use domain specific skills 3) Development of understanding 4) Change and individual personal growth Points of Focus Content Competence Meaning Growth From the data collected, teachers thus divide themselves into two categories, Transmissive Teachers and Interpretive Teachers. These categories are adopted from the Australian PEEL-project (Baird and Mitchell 1987; Baird and Northfield 1992). The transmissive teacher argues that good teaching is transmission of knowledge from teacher to student in order to develop abilities and understanding of the subject along the lines of - or in accordance with - the teacher’s abilities and understanding, whereas the interpretive teacher aims at enhancing the student’s understanding and conceptualising and plans teaching sessions where the students have the possibility of developing cognitive, metacognitive and domain specific abilities. In this case the aim of teaching is broader than strictly domain specific. 8 The students’ conceptions of reading The phenomenographic analysis of student interviews combined with questionnaires gave these results concerning the students’ conceptions of what can be achieved by reading fiction and poetry: Reading is the way to factual knowledge (knowledge about literary history, methods of literary analysis, knowledge of historical events, basis of essay writing). The students in this category simply said that they read literature in order to qualify for further education. Some of them read literature for school and only for school. Some of them also read for joy, but they did not see any connection between their reading for school and their reading for joy. They all had transmissive teachers. Reading is an escape from reality. The reading the students talk about here is their reading outside schools. These students all had transmissive teachers. Reading is a way to language construction. The students in this group talk about the way one refines one’s language by reading and meeting different authors’ ways of describing feelings and conflicts between human beings. Reading is a way to identification and enhanced understanding of other ways of conceptualising the world – and of acting. Reading is a way to enhanced personal insight and the ability to reflect upon oneself from an outsider’s view Reading implies change, not just of yourself as a person, but of your understanding and interaction with others Students within the last four categories (about 25%) are all from reading backgrounds, and they are all extensive readers. They have well established reading habits. This group had both transmissive and interpretive teachers. 9 In the classes visited in this study, the majority of the students (about 75%) resumed the roles of passive receptivity or relatively uninformed responding4. They came to class and listened and took notes, they did the group work which the teacher had decided and prepared beforehand, and in the interviews the majority did not understand the nature of the subject or know why they should do the things they were asked to do in class. Despite the fact that the teachers predominantly claimed that in class they were working with literature and interpretation of literary texts as the main task, the majority of students said in the interviews that they had Danish lessons in order to improve their punctuation and to learn how to write properly. The underlying aims in the lessons were not clear to these students. Many of the students were confused with respect to how to read and interpret a text. They read the text at home, and they brought to class suggestions for discussion, but they often realized that their suggestions were not appreciated. Little by little they gave up preparing the texts at home. They may have read the texts superficially, but they did not prepare the texts in the sense that they really put energy and reflection into the reading. They realized that it does not pay off to do so, as their reflections were not often considered in class. These students divided reading in two categories: for school and for joy. In classes where the students’ roles could be described as informed participation or informed collaboration, the majority of students saw a connection between reading for school and reading for joy, and some of them, who had not been reading literature before, started reading, and felt that they could manage. Study 2 showed that students changed their attitude to reading according to their teacher’s teaching practice. Major results of Study 2 The teacher observed in study 2 planned and carried out lessons and tasks in order to ensure that the individual student got a possibility of developing - his or hers personal conception of learning and rewarding study behaviour - a conscious and enhanced use of language - a competent and informed reader approach This was implemented through lessons and sessions where individual work, pairwork and group work took place in every lesson. Lessons where writing and thinking had their natural space, a lesson often started with the students writing down their own questions to the text. This work gave 4 See the categorisation in the beginning of the article 10 the teacher information about the individual student’s conception of learning and domain specific problems and challenges, in that way the teacher continuously had the possibility to plan work tasks which would challenge each student to read, write and reflect This meant lessons where everybody accepted and even liked the fact that working with texts is time consuming. Simultaneously the teacher and the class cooperated on establishing a class culture based on mutual respect with room for different personalities and cultures. The different interpretations were always discussed with respect for the individual student’s observations. After a year of this way of working the students’ evaluation was positive. 19 students were highly satisfied, and ten of these stated that they had started reading fiction on their own accord which they had not done before. Four students praised the variation and the opportunity of being creative. One person stated that he realised the importance of group work and the fact that you can learn from others while working in groups. One wrote that it had been a year full of challenges, and that she had finally understood what this subject was all about. One out of 26 students found the way of working “trivial” as he put it. When asked about their own contribution to the work of the year, 20 students answered that they had worked well. Five answered that their work had been ‘ok’, and one answered that he had not worked much. This student is also the student that found the lessons trivial. The reason was that he was an excellent reader even before he started 10th grade, and he had an academic background, and he wanted to be introduced to literature reading at a more advanced level. The students’ written exam papers were evaluated by an external examiner, who wrote that the most striking thing about the students´ essays was that they were all personally involved in what they wrote. They all had a personal approach to reading, interpretation of texts and writing about it. It was no surprise that the dissatisfied student had an excellent score. The major results of both investigations A teacher’s definition of the subject of Danish combined with his/her teaching practice is decisive for the non-reading student’s development in learning and reading. The students from reading backgrounds will go on reading, and their teachers’ conception of good teaching will not influence these students’ reading habits dramatically. 11 If the student is not an experienced reader, a transmissive teacher seems to breed reproductive, passive student behaviour. A dialogic, interpretive teacher who aims at enhancing the student’s metacognitive development and domain specific conceptualisation seems to produce active, probing student behaviour In figure 1 above these different positions are illustrated Finally and perhaps the most important factor of them all, the basis of progression is a joy of reading and a wish to work hard in the subject. When students know what the task is about, and feel that they are getting better day by day, their joy of working increases. A lot of educational research takes for granted that there is a close connection between a student’s conception of learning, approaches to learning and learning outcome. The relevance of studying these areas may be found in the fact that despite the change in student uptake in upper secondary education in Denmark, the number of students from families with little formal education who obtain a university degree, have not changed radically (Hansen 1995). The reasons for this are multiple. One reason is that these young people do not get access to what Jerome Bruner calls ‘cultural codes’ (Bruner 1998). Danish Language and Literature have a central position in building this access to cultural tools so that the students can see their lives and their own role in this in a wider and more reflective perspective. For that reason it is of utter importance that the central issues of language and literature form a never-ending dialogue in the student’s consciousness. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. The area is important for political, sociological and humanistic reasons, and continuous, detailed classroom research is necessary in order to cover this area. 12 Literature Baird, J. and I. Mitchell (1987). Improving the Quality of Teaching and Learning, An Australian Case Study - The PEEL Project. Melbourne, Melbourne University. Baird, J. and J. r. Northfield (1992). Learning from the PEEL Experience. Melbourne, Melbourne University. Boulton-Lewis, G. M., D. J. H. Smith, et al. (2001). "Secondary Teachers' conceptions of teaching and Learning." Learning and Instruction 36(1): 35-51. Bruner, J. (1998). Uddannelseskulturen. København, Munksgaard. Hansen, E. J. (1995). En generation blev voksen. København, Socialforskningsinstituttet Rapport 95:8. Huber, Günter L., and Maria Schmidt. "Uncertainty Vs. Certainty Oriented Students' Decision Making in Learning Processes." Paper presented at the 6th European Conference for Research on Learning and Cognition, Nijmegen, Netherlands 1995. Marton, F., G. Dall'Alba, et al. (1993). "Conceptions of Learning." International journal of Educational Research 19(3): 277-300. Meyer, E. (2000). An overview of the development and application of the Reflections on Learning Inventory (RoLI). The RoLI Symposium, Imperial College, London. Meyer, J. H. F. and G. M. Boulton-Lewis (1997). Variation in students conceptions of learning: An exploration of cultural and discipline effects. Pintrich, P., D. Smith, et al. (1991). A Manual for Use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire. Michigan, National Center for Research to Improve Post-Secondary Teaching and Learning. Prosser, M. and K. Trigwell (1999). Understanding Learning and Teaching. Buckingham, Open University Press, UK. 13