Guide to Introductory Human Geography Courses

advertisement

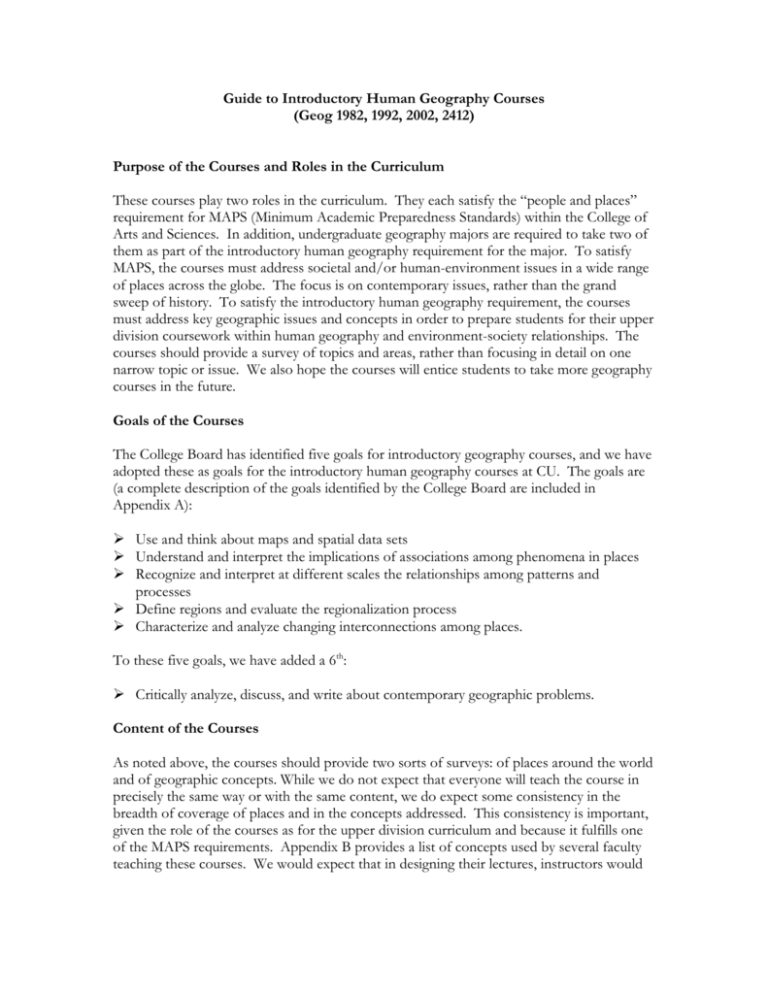

Guide to Introductory Human Geography Courses (Geog 1982, 1992, 2002, 2412) Purpose of the Courses and Roles in the Curriculum These courses play two roles in the curriculum. They each satisfy the “people and places” requirement for MAPS (Minimum Academic Preparedness Standards) within the College of Arts and Sciences. In addition, undergraduate geography majors are required to take two of them as part of the introductory human geography requirement for the major. To satisfy MAPS, the courses must address societal and/or human-environment issues in a wide range of places across the globe. The focus is on contemporary issues, rather than the grand sweep of history. To satisfy the introductory human geography requirement, the courses must address key geographic issues and concepts in order to prepare students for their upper division coursework within human geography and environment-society relationships. The courses should provide a survey of topics and areas, rather than focusing in detail on one narrow topic or issue. We also hope the courses will entice students to take more geography courses in the future. Goals of the Courses The College Board has identified five goals for introductory geography courses, and we have adopted these as goals for the introductory human geography courses at CU. The goals are (a complete description of the goals identified by the College Board are included in Appendix A): Use and think about maps and spatial data sets Understand and interpret the implications of associations among phenomena in places Recognize and interpret at different scales the relationships among patterns and processes Define regions and evaluate the regionalization process Characterize and analyze changing interconnections among places. To these five goals, we have added a 6th: Critically analyze, discuss, and write about contemporary geographic problems. Content of the Courses As noted above, the courses should provide two sorts of surveys: of places around the world and of geographic concepts. While we do not expect that everyone will teach the course in precisely the same way or with the same content, we do expect some consistency in the breadth of coverage of places and in the concepts addressed. This consistency is important, given the role of the courses as for the upper division curriculum and because it fulfills one of the MAPS requirements. Appendix B provides a list of concepts used by several faculty teaching these courses. We would expect that in designing their lectures, instructors would attempt to cover many – but by no means all – of the concepts. One way to think about whether coverage is adequate is to refer to introductory human geography textbooks. Recitations Recitations are an important part of the introductory courses. They provide students the opportunity to critically engage the issues discussed in readings and lectures and are settings in which questions can be resolved. In addition, the critical writing and spatial data components of the course will likely be addressed in recitation. In order to integrate the recitations into the course and to ensure some consistency across recitation sections, it is useful to have a lesson plan for each recitation that includes the content and analytical objectives of each recitation, a description of the ways that the recitation is supposed to relate to the lecture portion of the course, the readings, and questions or issues that will guide the recitation activities (e.g., discussion, debate, role-play, homework assignment, etc.). Some instructors have also found it useful to require that students hand in answers to questions about each week’s readings. Most instructors hold weekly TA meetings to discuss upcoming recitations. In general, there will be one recitation for each week of lecture. There are, of course, exceptions that instructors may want to make, including the first of the semester, weeks when exams are scheduled, and so forth. Instructors may want to consider compiling some form of recitation manual that provides students with the weekly recitation goals, reading assignments, background materials, and discussion questions. These manuals may be put on-line or printed and sold through the University Bookstore. Either of these means of distributing the recitation material means that every student will have advance access to the materials and can be held accountable for being prepared in class. If the recitation manuals are sold in the bookstore, a royalty can be added that will be rebated to the department. These royalty funds may be used to hire students or other assistance to compile recitation materials in the future. We discourage using the department copier for reproducing recitation packets for each recitation. With approximately 1,200 students enrolled in the introductory human geography courses each semester, the cost of copying all the necessary materials for students is prohibitive. If material is not made available on a course web-page or recitation manual, instructors should make the material available through the Library’s electronic reserve or through the reserve desks at either Norlin Library or Earth Sciences Library. Instructors should be aware, however, that extensive reliance on reserve material dramatically reduces the likelihood that students will have read the course material before class. We have plans (or perhaps more accurately, ideas) for a recitation bank in which faculty and other instructors would share the ideas, lesson plans, and teaching materials for recitations. This does not yet exist, but instructors should feel free to talk with others who have taught the introductory courses for ideas about what worked in recitation and what didn’t. In addition, most of the introductory geography texts include curriculum materials for recitations, a CD with recitation source material, and so forth. There isn’t much reason to start from scratch unless you really want to. Grading and Workload Instructors should expect to set the mean grade for the course at 2.5, or C+/B-. The overall grade would include grades on a variety of activities: exams, critical writing assignments, homework, discussion, and so forth. The College of Arts and Sciences requires that recitation grades account for no more than 50% of the course grade. Standardizing the grading across recitations is one of the most vexing problems in the courses. Curving the grades for exams and the recitations is one way to handle the issue, and to ensure that there are not dramatic differences in the grades across recitations. This means that a TA with 100 students (or four recitation sections) should strive for a distribution of about 10-15 A’s, 35-40 B’s, 35-40 C’s, and 10-15 D’s and F’s. Since these classes typically have over 100 students in them (and sometimes up to 500), students can be expected to curve themselves if the TA’s (and instructors) are at all critical in their evaluation. That said, TAs will need clear instructions as to the expected grade distribution for their recitations. In general, students should expect to spend 3-4 hours per week outside of class for each credit hour. Since the introductory courses are three credits, one should expect them to work 9-12 hours per week on reading, assignments, studying for exams, and so forth. As might be expected, however, students often have different ideas about how much effort they should have to expend. In addition, instructors need to be aware of the way that their assignments affect the workload of their TA’s. A 50% appointment is for up to 20 hours per week; this may be modified as some weeks (e.g., when grading papers) may require more work and other weeks will require less (e.g., the week of fall break). Assignments or “graded events” will likely be of several forms, including exams, participation in recitation, homework assignments, a special project, and writing. While there is considerable flexibility, it is expected that each course will include at least 2 exams and at least two critical writing projects of about 3-5 pages, or some equivalent kind of project. Administrative Matters Administering a course of 250 or more undergraduates is daunting. Instructors will be faced with managing upwards of 7 teaching assistants, dealing with room scheduling problems, student needs and complaints, and so on. A few suggestions and pointers may help with these matters. 1. Wait lists. Very often the courses have extensive wait lists, particularly fall semester. Students can only enroll in the course through recitations and recitations are capped – absolutely – at 25. The wait lists vary, however, across sections and across the classes, so students may want to put their name on a different section. It is also possible to rearrange the wait lists for sections, and Darla Shatto generally handles these matters. If you want to rearrange the wait lists, remember that what you do will affect other students on the list. And remember, while many students require the course to graduate, it is generally not a problem if they cannot get into the course in a given semester. If students are on the wait list and are not able to enroll in a given semester, they are given the highest priority for the course in the next semester. 2. Administrative drops. If a student misses two classes in the first two weeks, you may ask Darla to make an administrative drop; this opens a space for students who have been attending class but who are on the wait list. It is not feasible to call roll in the lecture, so recitations are generally where attendance is taken. Since the time frame is rather tight, it is often useful to hold recitations the first week of the semester so that there is an opportunity to identify students who are not in attendance. 3. TA coordination. You may have as many as 25 recitations for your course, depending on the overall enrollment. Even with a course of “only” 250 students, you may have up to 5 teaching assistants. Given that the teaching assistants will have differing skill levels, differing familiarity with the topic (some will never have taken a human geography course), and given the importance of recitations to the course, a TA meeting every week is almost a necessity. Coordination between teaching assistants and instructors will be very important in making the course run smoothly. This will also be your opportunity to ensure that teaching assistants are teaching what you want taught. Each TA is an aspiring teacher and will want to impart his or her own ideas onto the recitations. As an instructor, you will have to balance that desire with your concern for the overall integrity of the course. 4. Lead TA. If your class is large (500 or more) and you have several teaching assistants, you may be able to have a Lead TA assigned to the course. This is not assured, however, as it depends on the availability of students and funds to fill this role; it is most likely provided in the larger sections or to instructors teaching multiple sections of a course. Typically this is a student who has taught the course (either as a TA or instructor) and who has good administrative skills. If you are assigned a Lead TA, he or she will either have a reduced teaching load (3 recitations rather than 4) or receive additional pay. The Lead TA can be used to help manage recitation lists, manage grading, manage a course web-site, prepare materials for the TA meetings, help put materials on reserve, and so forth. 5. Textbooks. Finding a good textbook is difficult and students love to complain about them. Nevertheless, we strongly encourage the adoption of a textbook because students use them as a resource and they provide a structure for a survey course (which these courses are). New instructors should talk with people who have taught the class previously about the merits of various texts and should gain approval from other instructors if they decide they do not want to use a text. 6. Testing and scanning services. Most of the introductory classes rely on multiple choice examinations that are graded by the Testing and Assessment Center. Scanning can generally be done within a day or two, and grades can be printed in several formats and written onto disk. The department pays for scanning. The Testing and Assessment Center offers workshops on how to prepare test keys, the ways information can be formatted, and so forth. The Testing and Assessment Center will tell new instructors that they must attend a workshop, but in truth, it is not required. 7. Cheating, academic dishonesty, behavior problems. It is awful, but you are likely to confront some problems along these lines at some point. The department has a code of conduct and a statement of the procedures that will be followed, and the campus has adopted a new code of conduct. Include these in your syllabus, as well as a statement of your own expectations. If these are announced in advance, you will have the protection you need to take action. While these guidelines and statements are helpful, you should also feel free to talk with other instructors and the department chair about how to handle problems. The most important thing is not to let a class get derailed by a disruptive student or by cheating problems. 8. Plagiarism. In the specific case of plagiarism, the university has arranged a site license for an on-line service that can be used to check student papers for plagiarism and for purchased papers. The web-site is http://www.colorado.edu/academics/honorcode/. Ask your students to turn in a disk copy of their papers and they can be compared with essays in the service’s “library.” 9. Resources for students. Students seem to be under enormous stress these days, and some are likely to have difficulties while in your class. Many (but by no means all) of the students facing these difficulties are non-traditional students, first year students, first generation college students, and/or students of color. If you suspect that a student is having problem or a counseling center contacts you please try to be supportive of the student. Remember, however, that you cannot serve as their therapist or friend. The counseling centers on campus are quite helpful, and can give you guidance with regard to how best to deal with the student. In addition, there are several centers on campus that will contact you for mid-term reports on a student. The advisors assigned to these students can also provide guidance in terms of how best to work with a student. While they are concerned about the student, they rarely advocate for them. Finally, there are tutoring centers on campus that can assist students with study skills and with the particulars of your course. 10. Student illnesses and absences. The random absence from class is generally not a problem, but you are likely to confront some outbreaks of mysterious contagious diseases around exam time (one intro class had an outbreak of appendicitis, with 6 students claiming to be stricken on the morning before the final exam) and two days before and after holidays. Announce your policy about absences, illnesses, and make up work in the syllabus and then stick to it. Announce the exam dates in the syllabus, as well. Many students will want to leave before the final exam. Do not encourage this! Announce the time and place of the exams on the syllabus and at the beginning of the semester; tell the students not to make travel plans that conflict with the exam schedule. 11. Religious/spiritual observance. Don’t schedule exams or required activities on religious holidays. Check the calendar before you set the syllabus. 12. Students with learning disabilities. You can expect that at least one student will have a documented learning disability or some condition that requires modification of the course; this may be in the form of allowing an interpreter, allowing extra time for exams, or a cognitive problem that makes reading or writing difficult. You will need to adjust to meet the needs of these students, but only if they have documentation from the appropriate oncampus office. You should include a statement to effect in your syllabus and ask students to provide the documentation within a month or before the first assignment. First year students rarely have all the documentation they need, so you may want to take that into consideration. 13. Final exam scheduling problems. Students who have more than three final exams scheduled for any given day can request that the last exam be rescheduled. The printed schedule of courses details the procedures students must follow to reschedule their exam, and instructors should also include this information in their syllabus. Generally, students must provide documentation of the four exams to the instructor by the 6th week of the semester. If the student does not do this or if the exam is not the last exam of the day, instructors are not obligated to make other arrangements for the student. These are the rules, but in practice, students often find that the last instructor will not reschedule the final or may want to reschedule a different exam in order to get a break in the day. 14. Incomplete grades. The University and the College have very clear guidelines with regard to incomplete grades. Students are not to ask you for them; you are to offer it. They should only be offered in extraordinary circumstances, and not certainly not because a student did not complete his or her work. If you decide to grant an incomplete grade, you and the student must fill out a form (available in the department office) that amounts to a contract for completion of the course. It sets the length of time the student will have (and you have discretion as to whether it is a week or a year) and how the completed work will be evaluated. Remember that you will be responsible for evaluating the late work and assigning the grade, not the person who is teaching the course next year or next semester. Do not require students to take the course again. If the student is so far behind as to make that seem a reasonable strategy, the student is better off dropping the course. You cannot compel a future instructor to accommodate your students. In general, an IF (Incomplete – Fail) should be given, rather than an IW (Incomplete – Withdraw). In the former, students receive a grade of F if they do not finish their work according to the contract signed by both of you, whereas the latter withdraws them from the class. Remember that the student’s enrollment likely meant that some other student was unable to enroll in the class. Expectations of Teaching Assistants As implied above, managing the teaching assistants can sometimes be difficult. This is rarely because a TA is recalcitrant or trying to shirk responsibilities; most often, it is because neither the instructor nor the TA has a clear set of expectations about the job or its relation to the course. In general, here is what you can expect of a TA: 1. A 50% TA should expect to work an average of 20 hours per week and to lead 4 recitations per week. A 37% TA will have 3 recitations and work an average of 15 hours/week. A 25% assistant will have 2 recitations and work an average of 10 hours/week. 2. You can require that assistants attend lecture, even if they have assisted you previously. Students will want to talk with them and courses are never the same. 3. Each TA should have at least 2 hours of office hours per week; office hours should be included in the syllabus or class web-page and should be announced in class. Office hours should be at a fixed time and place each week. Extra hours or appointments can be added, but the TAs are expected to hold their regular hours. 4. Each TA should attend the weekly TA meeting. Lecture, meetings, office hours, and class time should be counted in the weekly workload. 5. Being a TA implies responsibilities beyond the classroom. Within the time limits identified above, they should expect to assist you with preparation, collation, and administration of exams and assignment of grades. Exams in particular may require additional work. They should also expect to assist you with copying course materials if needed, carrying stuff to lecture, putting materials on reserve, and so forth. This may mean that the workload is a bit uneven, but there are some weeks when they won’t have recitation. The workload should average out. 6. Each TA is expected to be available for work 1 week before class, and up to one week after grades are assigned. That means that a TA should not expect to show up the first day of lecture and leave the last day of lecture. 7. Each TA will be assigned a set of recitations to lead. They are responsible for being at each of those recitations. Obviously, things come up, and a TA may need to be absent from one or two recitations. In that event, the TA needs to make arrangements to have the class covered by another TA; these arrangements should be approved by you in advance. 8. If you are having difficulty with a TA, you should talk first with the TA, and then with the department chair to resolve the difficulty. Graduate students are evaluated each year, and your comments about students that have been your TA are taken seriously. The department needs good information about student performance as teaching assistants in order to enhance the program overall and to give students the help they need in becoming good instructors. Appendix A College Board Goals for Introductory Human Geography (Source: www.collegegoard.com/ap) Use and think about maps and spatial data sets. Geography is fundamentally concerned with the ways in which patterns on Earth’s surface reflect and influence physical and human processes. As such, maps and spatial data are fundamental to the discipline, and learning to use and think about them is critical to geographical literacy. The goal is achieved when students learn to use maps and spatial data to pose and solve problems, and when they learn to think critically about what is revealed and what is hidden in different maps and spatial arrays. Understand and interpret the implications of associations among phenomena in places. Geography looks at the world from a spatial perspective – seeking to understand the changing spatial organization and material character of Earth’s surface. One of the critical advantages of a spatial perspective is the attention it focuses on how phenomena are related to one another in particular places. Students should thus learn not just to recognize and interpret patterns, but to assess the nature and significance of the relationships among phenomena that occur in the same place and to understand how tastes and values, political regulations, and economic constraints work together to create particular types of cultural landscapes. Recognize and interpret at different scales the relationships among patterns and processes. Geographical analysis requires a sensitivity to scale – not just as a spatial category but as a framework for understanding how events and processes at different scales influence one another. Thus, students should understand that the phenomena they are studying at one scale (e.g., local) may well be influenced by developments at other scales (e.g., regional, national, or global). They should then look at processes operating at multiple scales when seeking explanations of geographic patterns and arrangements. Define regions and evaluate the regionalization process. Geography is concerned not simply with describing patterns, but with how they came about and what they mean. Students should see regions as objects of analysis and exploration and move beyond simply locating and describing regions to considering how and why they come into being – and what they reveal about the changing character of the world in which we live. Characterize and analyze changing interconnections among places. At the heart of a geographical perspective is a concern with the ways in which events and processes operating in one place can influence those operating at other places. Thus, students should view places and patterns not in isolation, but in terms of the spatial and functional relationship to other places and patterns. Moreover, they should strive to be aware that those relationships are constantly changing, and they should understand how and why change occurs. Appendix B Key Geographic Concepts – Sample List General geographic Space Place Region and regionalization Scale Diffusion Globalization Time-space convergence Spatial interactions and dependence Geographical imagination Economic Fordism and post-Fordism Space-economy Spatial and gender divisions of labor Structural adjustment Commodity chain Uneven development Sustainable development Population Migration Demographic transition Malthus Carrying-capacity Fertility Political Nation and state Multi-national states Colonization, de-colonization, neocolonization Heartland, rimland, shatter-belts Balkanization Sphere of influence Core-periphery relations Hegemony Social/cultural/landscape Culture Society Landscape Moral and symbolic landscapes Hybridity Contact zones Enclaves Segregation Urban Urbanization, urbanism Shock cities Systems of Cities Central place theory Environmental Nature Green Revolution Desertification Patterns of agriculture Resources Environmental Justice Agriculture