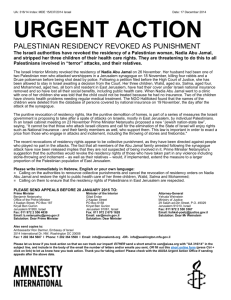

The Quiet Deportation: Revocation of Residency of East

advertisement