Model answers to publisher`s essay tests for Ch. 6

advertisement

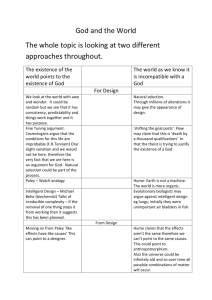

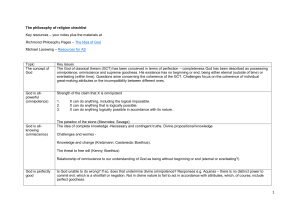

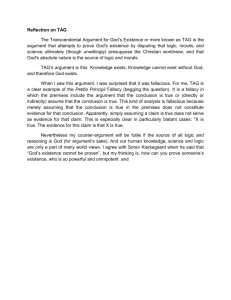

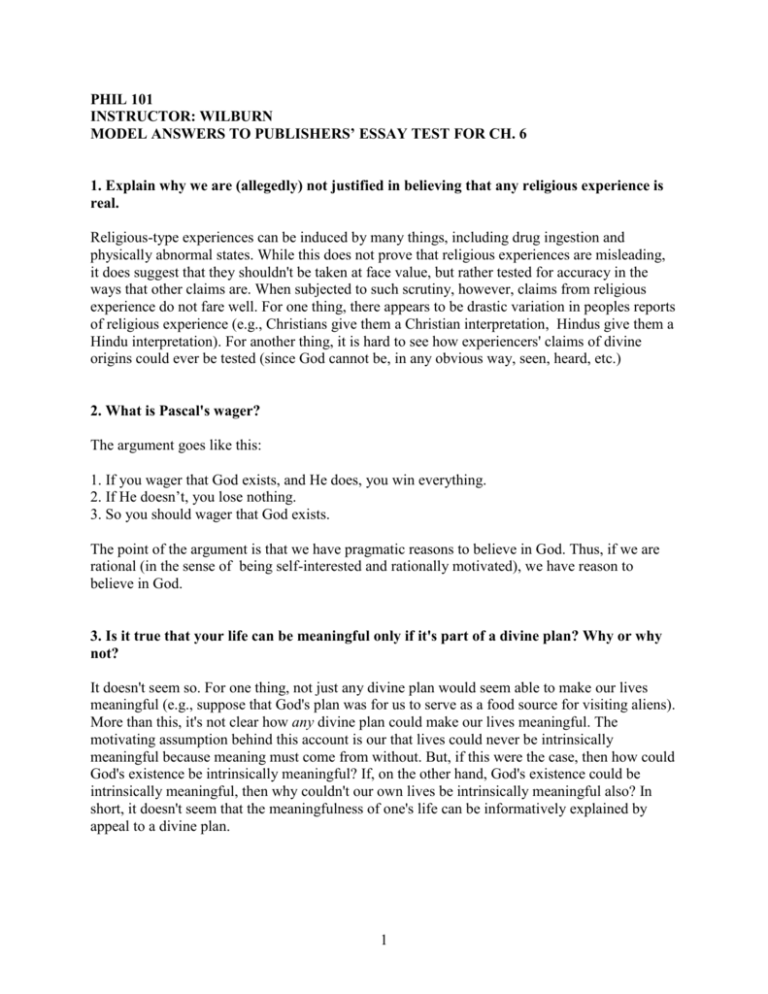

PHIL 101 INSTRUCTOR: WILBURN MODEL ANSWERS TO PUBLISHERS’ ESSAY TEST FOR CH. 6 1. Explain why we are (allegedly) not justified in believing that any religious experience is real. Religious-type experiences can be induced by many things, including drug ingestion and physically abnormal states. While this does not prove that religious experiences are misleading, it does suggest that they shouldn't be taken at face value, but rather tested for accuracy in the ways that other claims are. When subjected to such scrutiny, however, claims from religious experience do not fare well. For one thing, there appears to be drastic variation in peoples reports of religious experience (e.g., Christians give them a Christian interpretation, Hindus give them a Hindu interpretation). For another thing, it is hard to see how experiencers' claims of divine origins could ever be tested (since God cannot be, in any obvious way, seen, heard, etc.) 2. What is Pascal's wager? The argument goes like this: 1. If you wager that God exists, and He does, you win everything. 2. If He doesn’t, you lose nothing. 3. So you should wager that God exists. The point of the argument is that we have pragmatic reasons to believe in God. Thus, if we are rational (in the sense of being self-interested and rationally motivated), we have reason to believe in God. 3. Is it true that your life can be meaningful only if it's part of a divine plan? Why or why not? It doesn't seem so. For one thing, not just any divine plan would seem able to make our lives meaningful (e.g., suppose that God's plan was for us to serve as a food source for visiting aliens). More than this, it's not clear how any divine plan could make our lives meaningful. The motivating assumption behind this account is our that lives could never be intrinsically meaningful because meaning must come from without. But, if this were the case, then how could God's existence be intrinsically meaningful? If, on the other hand, God's existence could be intrinsically meaningful, then why couldn't our own lives be intrinsically meaningful also? In short, it doesn't seem that the meaningfulness of one's life can be informatively explained by appeal to a divine plan. 1 4. What is the best explanation design argument? The best explanation design argument is the kind of argument which proceeds as follows: 1. The universe exhibits apparent design 2. The best explanation of this apparent design is that it was designed by a supernatural being. 3. Therefore it’s probable that the universe was designed by a supernatural being, namely, God. 5. How does Descartes’ ontological argument differ from Anselm's? Anselm’s argument goes as follows: 1. God, by definition, is the greatest being possible. 2. If God exists only in our minds, then it is possible for there to be a being greater than God, namely a being like God that exists in reality. 3. But it is not possible for there to be a being greater than God. Descartes’ argument goes as follows: 1. God, by definition, possesses all possible perfections. 2. Existence is perfection. 3. Therefore, God exists. This difference in formulation allows each argument to be defeated in slightly different ways. Anselm is defeated by the observation that something can exist only in the understanding, whereas Descartes argument suffers from its supposition that existence is a property. The first assumption is defeated by the observation that something can exist in the understanding in the sense of being an uninstantiated idea (which is in no way contradictory). The second assumption is undermined by the observation that to speak of anything at all as having properties is to already suppose that it exists. This makes the real conclusion of Descartes argument the following: “If God exists, then He exists.” 6. Does the argument from evil succeed in showing that there is no God? Why or why not? The problem of evil is the following: 1. Evil seems to exist. If God were all-knowing, he would know that evil exists. 2. If he were all good, he would want to eliminate evil. 3. If he were all-powerful, he would be able to eliminate evil. 4. Thus, the existence of evil disproves the existence of God. Whether or not this argument is effective is very much up to debate. One response to it is to deny that God has all three of the properties typically ascribed to him (e.g., omnipotence, omniscience 2 and omnibenevolence). Alternatively, one might try to argue that evil is illusory, or that at least some forms of evil are an inevitable consequence of God's gift of human free will. 7. In Hick's theodicy, in what way is God paternalistic? God is paternalistic, on Hick's account, because he allows us to suffer for our own good. To this extent, God uses us (by allowing us to suffer in ways that limit our freedom) ito the end of promoting our own spiritual development or moral character. 8. Can believing something to be true make it true? Why or why not? Sometimes this may indeed occur, as when self-confidence improves performance a selfinculcated belief in the goodness of people elicits the decency of others. In none of the cases, however, are the beliefs in question completely unfounded, since we often have good evidence that self-confidence improves performance and that courtesy toward others makes us likable. Thus, they are not examples of a state of affairs being brought about by blind faith. 9. Explain why Bertrand Russell thinks that passionate belief in God is nothing to admire. Russell thinks that the more passionate a belief is, the less likely it is to be true, since true beliefs are likely to be supported by evidence, and beliefs supported by evidence are likely to be held with calm conviction rather than passion. Thus, he suspects that passionate belief about religion (or anything else for that matter) is likely to a symptomize intellectual irresponsibility. 10. Does being an atheist or nontheist prevent one from being a deeply religious person? Why or why not? One might think that people can have a religious attitude toward life (reflected in both the kind of lives they lead and the kinds of people they are) without subscribing to any particular set of theistic beliefs or doctrinal convictions. If so, then perhaps religion (of a sort) without God is possible. On this account, a belief in a personal (or impersonal) God is neither necessary nor sufficient for “religion.” 3