The Velvet Glove - Open Evidence Archive

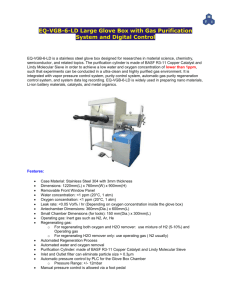

advertisement