Conservation Action Plan - Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden

advertisement

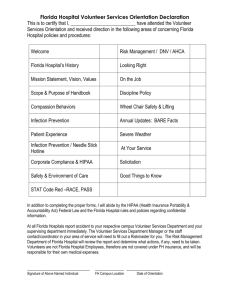

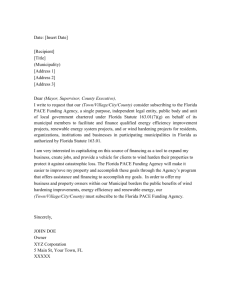

Conservation Action Plan Opuntia corallicola Species Name: Opuntia corallicola (Small) Werderm. Common Name(s): Florida semaphore cactus, Key’s semaphore cactus Synonym(s): Opuntia spinosissima Miller (1768), Cactus spinosissimus (Miller) Martyn (1771), Consolea spinosissima (Miller) Lemaire (1862), Consolea corallicola Small (1930) (Austin 1980). Extensive discussion of taxonomy in Bradley and Gann (1999). Family: Cactaceae Species/taxon description: Shrub or small tree 1-3.5 m (3.3-11.5 ft) tall, trunk cylindrical; branches usually grow in one or multiple planes from the trunk; copiously spiny, gray or white, in all areoles or some joints nearly spineless, spines not barbed; flowers orange turning to red as they age (Bradley and Gann 1999), unfertilized flowers revert to vegetative branch or drop as dispersal unit; fruits yellow (Coile 2000, Austin 1998). Legal Status: Florida endangered, critically imperiled (FNAI), Federal candidate. Biogeographic Value: Endemic. Prepared by: Jennifer Possley, Meghan Fellows and Cynthia Lane, Samuel J. Wright, Conservation of South Florida Endangered and Threatened Flora, Research Department, Fairchild Tropical Garden Last Updated: June 2004 (Wright and Maschinski) M. Fellows Background and Current Status Range-wide distribution – past and present Florida: (confidential) Population and reproductive biology/life history Annual/Perennial: Perennial Habit: Shrub/Small Tree Short/Long-Lived: Long Pollinators: Bees, hawkmoths, hummingbirds, bats? (Bradley and Gann 1999). Birds? (Austin et al., 1993). The pollinator for O. corallicola is unknown. Flowering Period: Flower throughout the year, peaking December to April (NegronOrtiz, 1998). Peak in February and March (Bradley and Koop 2003) Fruiting: Rare; Laura Flynn (The Nature Conservancy) tried to pollinate flowers and got viable fruit, but when planted, they failed to thrive. Annual variability in Flowering: unknown Growth Period: a study by Bradley and Koop (2003) showed that juveniles (plants without pads) had significant growth between August and November, while adults (plants with pads) showed significant growth between April and June. Dispersal: Primarily through dropped pads that have spines. Seed Maturation Period: unknown Seed Production: low and infrequent Seed Viability: Fruit collected prior to May 1995 (no seed germinated), and twice in 1997 (June/July collection -seeds did germinate, July 7, 1997 fruits/seeds were not successfully germinated) (Vlcek, 1997). Regularity of Establishment: Never observed from seed, easy from dropped pad in fresh water. Germination Requirements: unknown Establishment Requirements: It is unknown whether the cactus roots better in one season than another. Population Size: (confidential) Annual Variation: Slow decline in number of adults, random in number of rooted pads. Number and Distribution of Populations: (confidential) Habitat description and ecology Type: MARITIME HAMMOCK, COASTAL STRAND. Low buttonwood transition areas between rockland hammocks and mangrove swamps and possibly other habitats such as openings in rockland hammocks (Gann et al. 2002); Rocky hammocks, coastal barrens (Coile 2000); Research suggests that different habitats are better for newly establishing plants vs. established plants. Physical Features: Soil: Cracks in limestone or shallow soil, sand (Austin, 1980); “Like its associates, the tree cacti this semaphore grows on almost bare rock. Soil is scarcely necessary; a little humus about the roots seems to be sufficient to furnish it with food” (Small, 1930). Elevation: < 1.5 meter above sea level Aspect: unknown Slope: unknown Moisture: unknown Light: Studies have tested growth and survival in full sun vs. shade. Results showed many interactions. Plants in shade survived, but did not grow well; plants in sun grew, then died. At Site 94, the adults are in a mixture of sun to shade, although adults in shade appear healthier than adults in sun. At Site 166, all plants are on the edge of a hammock, in partial shade. Biotic Features: Community: “It is to be expected on any of the Florida Keys where there are primeval hammocks” (Small, 1930); at Site 94, occurs in a low buttonwood transition area between rockland hammock and coastal swamp. (O. spinosissima). Bare rocks with slight covering of humus in jungle hammocks near sea level (Benson, 1984). At Site 166, plants occur in the ecotone between mangroves and hammock species. Interactions: Competition: unknown Mutualism: unknown Parasitism: unknown Host: Other: unknown Animal use: One experimental outplanting appeared to be trampled by deer – perhaps they were eating the cacti or browsing nearby. Natural Disturbance: Fire: highly unlikely Hurricane: Hurricane Georges caused some damage to the plants; however hurricanes could be viable dispersal mechanism and increase the number of rooted plants Slope Movement: unknown Small Scale (i.e. Animal Digging): unknown Temperature: unknown Protection and management Summary: Ninety-six clones were planted in 1996, but these populations continue to decline due to a pathogen, deer trampling, etc (Stiling, Rossi and Gordon, 2000). University of South Florida: Dr. Peter Stiling of USF is attempting a reintroduction on Site 167 (Bradley and Gann 1999). The Cactoblastis moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) is being monitored at one site by The Nature Conservancy and Stiling. Availability of source for outplanting: (confidential) Availability of habitat for outplanting: (confidential) Threats/limiting factors Natural: Herbivory: The moth Cactoblastis cactorum is a major problem (Johnson and Stiling, 1996). Larvae much prefer O. corallicola to the other Opuntia species. The Nature Conservancy had placed protective cages over the cacti (Stiling, Rossi and Gordon, 2000), but they are now removed. No moth activity was observed in 228 plants of Opuntia corallicola at Site 166 (Pemberton, pers. comm.). Disease: Unknown pathogen or fungus attacking juveniles (Bergh, pers. comm.) Predators: Key deer trampling (Stiling, Rossi and Gordon, 2000) Succession: unknown Weed invasion: Exotic plants Schinus, and Colubrina (Bradley and Gann, 1999); although little has been seen recently at the two wild populations. Fire: very rare in habitat Genetic: The cacti at Site 94 ar not reproducing sexually; the original 12-13 are probably sterile polyploids derived from a single parent plant (Negron-Ortiz, 1998). Genetic studies have suggested that there are more than one genetic individual at the Site 94 (The Nature Conservancy, unpubl. data, 2001). It is unknown how many genetic individuals are in Site 166 population or if they are capable of reproducing sexually. Ongoing studies at Fairchild are addressing the genetic diversity and relatedness of the wild populations. Anthropogenic On site: Collectors (Bradley and Gann, 1999; Alcorn, 1990) Off site: Development, pollution. Collaborators The Nature Conservancy, Institute for Regional Conservation, Biscayne National Park, The Florida Fish and Wildlife and Conservation Commission Conservation measures and actions required Research history: The genus Opuntia originated in northern South America and later spread to the Caribbean, where it further diversified (Alcorn, 1990). Opuntia spinosissima was first discovered in South Florida in 1919. Historically, populations existed on Big Pine Key (now that land is residential) and Key Largo (Small, 1930). A population of 30 adults also existed on Big Torch Key. The population on Big Torch was extirpated by construction US 1, although plant enthusiasts reportedly moved some of the plants to protected public or private areas (Kernan, undated). The species was considered extinct in the wild. Then, a population of 16 adult Opuntia spinosissima was discovered on Site 94. This population may have been introduced from nursery stock cultivated from wild populations (George Avery’s field notes, as cited in Alcorn, 1990). In 1989, Carol Lippincott discovered Cactoblastis cactorum on Opuntia stricta plants in the Keys. In 1990, Cactoblastis cactorum larvae killed one of 13 remaining O. corallicola plants. Sometime in the late 80’s or early 90’s The Nature Conservancy purchased the land where O. corallicola was growing and designated it a preserve. By 1993, Florida Atlantic University, Fairchild Tropical Garden, The Nature Conservancy, University of South Florida, and USFWS had formed an O. corallicola recovery team. Austin and Binninger (1994) found that the Florida semaphore cacti are actually not O. spinosissima and should properly be called O. corallicola. This means the species is extremely endangered. Fairchild Tropical Garden received a grant from the National Biological Service from July 1, 1995 to July 1, 1996 to study “Conservation of Opuntia spinosissima in the Florida Keys.” Project goals were to “re-establish O. spinosissima in appropriate protected habitats through a carefully monitored reintroduction program and to increase our knowledge of the species’ reproductive biology.” Collaborators included the Nature Conservancy, University of South Florida, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, state and county natural resource agencies, and the National Key Deer Refuge. Reintroduction sites were Site 94, and Site 168. The source of plants for translocation was the 12 plants on Site 94. Peter Stiling, Kit Kernan, Doria Gordon, Anthony Rossi and Steve Karl applied for a National Science Foundation grant to study the relationship of Cactoblastis cactorum and Opuntia corallicola. (A publication appeared in Biological Conservation in 2000). Peter Stiling (1996) reported to Doria Gordon that the outplantings on Site 94 have gone well. Gordon and Kubisiak’s (1997) RAPD analysis supported Austin and Binninger’s belief that O. corallicola and O. spinosissima are two separate species. Vivian Negron-Ortiz (1997) completed her reproductive studies and published a paper saying that the plants may be sterile polyploids. Kit Kernan (1998) wrote a report about the results of Fairchild Tropical Garden’s reintroduction and monitoring efforts. The study showed that survival was lower when plants were in closed canopy hammocks. He suggested that adults do best in mature hammocks, but juveniles require canopy gaps, which explains why there are contradictions in the literature describing O. corallicola’s preferred habitat. A second or additional outplanting occurred at Site 50 under the direction of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection in 1996. This outplanting has had some success with approximately 1/3 of the plants surviving to 5 years. Janice Duquesnel continues to monitor for flowering, recruitment and survival, maintaining an accurate GIS map and tagging records. Plants were failing to thrive in ‘hammock’ sites and were removed. In November of 2001, Keith Bradley and Steve Woodmansee of the Institute for Regional Conservation discovered a population on a remote island (Site 166) of Biscayne National Park. In January of 2002, Bradley led a team of researchers from Fairchild Tropical Garden and Bob Pemberton from the United States Department of Agriculture back to the site to assess the distribution and size of the population. During the January visit Pemberton collected 228 dead cladodes. Lab inspection revealed no evidence of Cactoblastis cactorum on cladodes. The site was visited another eight times from August 2002 through June 2003. During the visit plants were tagged, mapped and monitored for survival, growth, and flowering. Material was collected by Fairchild from 70 individuals to study the level of genetic variation within and between the two populations. In addition Bradley has surveyed islands containing suitable habitat and has found no O. corallicola (Bradley and Koop 2003). In fall of 2002 Fairchild donated 43 O. corallicola plants to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Planted material was grown from collected cladodes of nine plants from Site 94. Carol Lippincott collected the cladodes in 1990. Those plants in addition to 15 more were outplanted at Site 50 in February and March 2003. Plants will be monitored for growth, survival and Cactoblastis cactorum occurrence. Genetic analysis of populations at Site 94 and Site 166 indicate that they are not distinct (Wright and Francisco-Ortega 2004). Vegetative reproduction is the main mode of reproduction in both populations. USDA researchers are examining effectiveness of biological controls of Cactoblastis cactorum on many Opuntia species, including O. corallicola. (Summary of Research in Progress/Completed) Phenology (Negron-Ortiz, Bradley and Koop) Genetics (Austin and Binninger, Gordon and Kubiasik, Pipoly, Francisco-Ortega, Lewis and Carriaga) Reproduction (Negron-Ortiz) Cactoblastis (Stiling, Pemberton) Horticulture (Garvue) Reintroduction (Garvue, TNC/Stiling, Lane et. al, Duquesnel) Growth & Survivorship (Kernan, unpublished, Bradley and Koop, Duquesnel) Mycorrhizae (Fisher) Establishment (Lane et. al) Genetic analysis (Francisco-Ortega and Lewis) Significance/Potential for anthropogenic use: The pads of some Opuntia spp. are eaten for food. Recovery objectives and criteria: There are no federal objectives or criteria for this species. Management options: Pest Removal The population at Site 94 appears to be in decline. Although doing nothing in most cases won’t increase the rate of the extinction, this species is subject to the invasion of the Cactoblastis moth. Current management efforts include weekly visits by volunteers, which remove moth larvae before they can destroy portions of the plants. Over the course of these frequent visits, a few larvae have hatched creating the need to remove the diseased pad. This species most likely requires some intervention if it is to survive the next 10 years, despite the discovery of the new population. Outplanting Outplanting success has been low, much more research is need to determine the necessary requirements for an outplanting. At this point, the most likely to be successful scheme would create canopy openings in hammocks farther from the coast than current locations either at the site of the current population or in nearby hammocks. Outplanting should be used to buffer the species from local extinction risk, given there are only two wild populations and two outplanted populations. Hand pollination Cross pollination of individuals at the two sites may be possible provided that individuals of both sexes are discovered. The species is somewhat slow growing, so hand crosses of pollination and whether or not they are successful could take years to determine. Next Steps: Continue monitoring of populations (wild or introduced) Coordinate more outplantings in suitable habitat References Alcorn, P.W. 1990. Element stewardship abstract for Opuntia spinosissima. Florida semaphore cactus. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA. Anderson, E.F. 2001. The cactus family. Timber Press, Portland Oregon. (as Consolea spinosissima). Austin, D.F. 1980. Status report on Opuntia spinosissima. In: Final report: endangered and threatened plant species survey in south Florida. USFWS, Office of Endangered Species. Austin, D.F. and D.M. Binninger. 1994? Final report on the endangered Florida semaphore cactus. Report to USFWS. Austin, D.F., D.M. Binninger, and D.J. Pinkava. 1998. Uniqueness of the endangered Florida semaphore cactus (Opuntia corallicola). Sida 18(2):527-534. Avery, G.N. and Loope, L.L. 1980. Endemic taxa in the flora of south Florida. Report T-558. U.S. National Park Service, South Florida Research Center, Everglades National Park. Pages 5-6. Barnhart, J.H. 1935. Chronicle of the Cacti of Eastern North America. Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 36(421):1-11. Benson, L. 1982. The cacti of the United States and Canada. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. Pp 537-538 (IN FTG LIBRARY). Bradley, K. and G. Gann. 1999. Status summaries of 12 rockland plant taxa in southern Florida. Report submitted to USFWS, Vero Beach, Florida, October 27, 1999. Bradley, K.A., and A.L. Koop. 2003. Population monitoring of Opuntia corallicola (Cactaceae) on Site 166, Biscayne National Park and Status survey in Biscayne National Park. Britton, N.L. and J.N. Rose. 1920. The Cactaceae: descriptions and illustrations of plants of the cactus family. Dover Publications, Inc., New York. Pages 204-205. Gann, G.D., K.A. Bradley, and S.W. Woodmansee. 2002. Rare Plants of South Florida: Their History, Conservation, and Restoration. The Institute for Regional Conservation, Miami, Florida. Garvue, D. 1994-1996. Various correspondences and memos regarding Opuntia spinosissima reintroductions in the keys. On file. Garvue, D. 1997. Conservation of Opuntia spinosissima in the Florida Keys. Final report to the National Biological Service, Washington D.C. Garvue, D. 1998. Endangered species profile: Florida semaphore cactus, Opuntia spinosissima. Garden News (Fairchild Tropical Garden) 53(5):12. Gordon, D.R. and T.L. Kubisiak. 1998. RAPD analysis of the last population of a likely Florida Keys endemic cactus. Florida Scientist 61(3/4):203-210. Howard, R.A. 1982. Opuntia species in the Lesser Antilles. Cactus and Succulent Journal 54(4):170-179. Johnson, D. and P.D. Stiling. 1996. Host specificity of Cactoblastis cactorum (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), an exotic Opuntia-feeding moth, in Florida. Environmental Entomology 25(4):743-748. Kernan, C(?). Late 90s?. Growth and survivorship of the endangered cactus Opuntia spinosissima reintroduced to the Florida Keys. Was in a file in Cynthia’s office. 13+pp. Negron-Ortiz, V. 1998. Reproductive biology of a rare cactus, Opuntia spinosissima (Cactaceae), in the Florida Keys: why is seed set very low? Sexual Plant Reproduction 11:208-212. Small, J.K. 1930. Consolea corallicola—Florida semaphore cactus. Addisonia 15:2526, pl. 483 Stiling, P. 1992. Report on the spread of Cactoblastis cactorum and its effects on native Florida cacti, and in particular, the rare semaphore cactus Opuntia spinosissima. Unpublished report sent to Doria Gordon. Stiling, P. No Date. Final report on Cactoblastis cactorum and its effects on native Florida cacti. Unpublished report sent to Doria Gordon. Stiling, P., A. Rossi, and D. Gordon. 2000. The difficulties of single factor thinking in restoration: replanting a rare cactus in the Florida Keys. Biological Conservation 94:327-333. Wright, S.J. and J. Francisco-Ortega. 2004. Determining Genetic Structure between populations of Opuntia corallicola. In Maschinski, J., K. S. Wendelberger, S. J. Wright, H. Thornton, A. Frances, J. Possley and J. Fisher. Conservation of South Florida Endangered and Threatened Flora: 2004 Program at Fairchild Tropical Garden. Final Report Contract #007997. Final Report to Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, FL.