Theodore Muir

advertisement

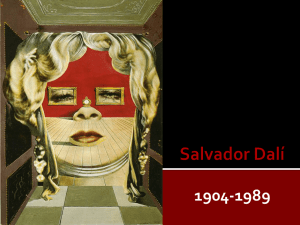

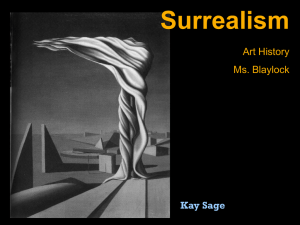

Muir 1 Theodore Muir Professor Kingsley English 101 June 16, 2008 Salvador Dali and the Paranoiac-Critical “Surrealists invite us to step beyond a utilitarian world…so that we can set foot in another world, altogether marvelous and mysterious” (“Lamplighter”). Surrealism had already possessed a foundation for its movement, but with the help of Dali the rest could be built. Salvador Dali’s contributions to the group linked the two worlds together as one through his process of activating the unconscious mind. Salvador Dali’s contributions to the movement helped redefine and strengthen Surrealism. Salvador Felipe Jacinto Domenech Dali was born twice. The first Salvador Dali had died three years before the boy who was to become the face Surrealism. Dali reasons that, “My brother was probably a first version of myself, but conceived too much in the absolute” (Dali and Haakon 2). Salvador Dali, as we know him, was born May 11th, 1904 in Figueras, Spain. As a boy Dali had many ambitions, however his earliest painting dates back to 1910 when he would have been six years old. Through the course of his career his style was influenced by many sources and Dali experimented with these until he was to find his own. Dali had found his muse, Gala, along with his style when he joined the Surrealist Movement in 1929. Muir 2 The aim of the Surrealist Movement was to achieve pure, uncensored, expression. The means by which Surrealists attempted to achieve this was largely influenced by the psychologist Sigmund Freud and his work with the psychoanalysis of dreams and the unconscious. Andre Breton, founder and leader of the movement, defines Surrealism as: “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express -- verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner -- the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern” (Surrealist Manifesto). Freud’s technique of free association was adapted by Breton as a tool for literature which he called “automatic writing” and later became a basis for all aspects of Surrealist arts in the form of automatism. While laying the groundwork for the movement, automatism fell short of satisfying its goals. The method was far too passive to invoke change on a larger scale. The Surrealist Movement desperately required a systematic approach of relaying the unconscious as automatism could not be applied to the broad scope that Surrealism wished to encompass such as the political and philosophical aspects of the movement. In order to satisfy its goals, Surrealism needed a fresh idea. Shortly after joining the movement, Salvador Dali would provide this idea when he refined his paranoiac-critical method. While automatism attempted to translate man’s unconscious to a medium, Dali had created a process by which to make “the world of delirium pass to the level of Muir 3 reality” (Finkelstein). This process was called the paranoiac-critical method and was described by Dali to be a “spontaneous method of irrational knowledge based on the critical and systematic objectivity of the associations and interpretations of delirious phenomena.”(Etherington-Smith 147) Dali would induce a state of madness onto himself but claimed “The only difference between myself and a madman, is that I am not mad!” (Finkelstein 64). Dali slipped into this state, but anchored himself to the real world in the back of his mind. This allowed Dali to visualize objects through his subconscious and interpret them. The result of this method often produced “double images” which Dali defines as “a representation of an object that is also, without the slightest physical or anatomical change, the representation of an entirely different object” (Finkelstein 62). Double images can be seen in many of Dali’s paintings from the 1930s such as The Invisible Man and Swans Reflecting Elephants. Breton praised Dali’s method for its application to all aspects of Surrealism (Spector 111). The paranoiac-critical method built upon the pre-existing Surrealist automatism, changing it from a passive to an active stance. Where previous automatism would transcribe the unconscious mind to media, paranoiac-critical reflected the unconscious mind onto reality and was then interpreted through media. For Surrealism it became “preferable to see in automatism ‘the functional form of thought,’ a logic of the image animated by desire rather than the ‘real functioning of thought’” (Jenny and Tretize 110). This new active automatism had its “aims at derealization” (Jenny and Treatize 110), that is, breaking down our rational thoughts of objects and reevaluating them with our subconscious. Dali claimed that “anyone engaging in the paranoiac-critical method would Muir 4 be able to demonstrate that ‘reality’ was not a fixed entity” (Greeley 469) Most people, at some point in their lives, will engage in the paranoiac-critical method themselves. If you have ever stared at the clouds and found images in the fluff, then you have practiced Dali’s method. Dali’s contributions to the movement through paintings, writings, films, his paranoiac-critical method, and role as de facto poster boy would outlast his membership. Just ten years after joining the movement, Dali was expelled from the group for supporting Francisco Franco following the Spanish Civil War. The expulsion would not discredit Dali in any regards to his influence of the movement. Dali had often claimed, which could arguably be true, that he was “more Surrealist than the Surrealist” (Finkelstein). Were it not for Salvador Dali, the Surrealist Movement would have been missing an entire dimension. With the help of the Sigmund Freud’s method of free association which so greatly influenced the movement I pose the question, what is the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of Surrealism? A Surrealist Movement without Salvador Dali is not Surrealism. Works Cited Dali, Salvador. The Secret Life of Salvador Dali. Trans. Chevalier, Haakon. Courier Dover Publications, 1993 Etherington-Smith, Meredith. The Persistence of Memory: A Biography of Dali. First. Da Copa Press, 1995. Finkelstein, Haim. "Dali's Paranoiac-Criticism or The Exercise of Freedom." Twentieth Century Literature 21(1975): 59-71. Greeley, Robin. "Dali's Fascism; Lacan's Paranoia." Art History 24(2001): 465-492. Jenny, Laurent. "From Breton to Dali: The Adventures of Automatism." Trans. Trezise, Thomas. October 51(1989): 105-114 Mottaz, Liz. "The Paranoiad Critical Transformation Method." 15 June 2003. Humboldt State University. 16 Jun 2008 <http://library.humboldt.edu/art/Artists/Dali_Salvador/Dali_Paranoid_Critical_Transformation.ht m>. Saladyga, Stephen. "Lamplighter." June 2006. Niagara University. 16 Jun 2008 <http://purple.niagara.edu/jlittle/lamplighter/saladyga.htm>. Spector, Jack. "Surrealism Redefined." Art Journal 53(1994): 108-111. .