Assessment of Current USAID/Liberia Program

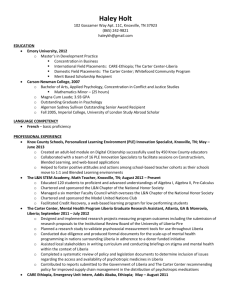

advertisement