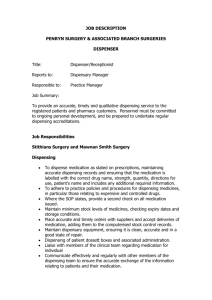

National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Program

advertisement

National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Evaluation of the Washington State National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing Exercise1,2. Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Randal D. Beaton, PhD, EMT, Research Professor Dept. of Psychosocial & Community Health University of Washington Captain Andy Stevermer, MN, ARNP Department of Health & Human Services Office of Emergency Response Julie Wicklund, MHP, Bioterrorism Surveillance & Response Program Manager Washington State Department of Health David Owens, Contingency Planner Office of Risk Management Washington State Department of Health Janice Boase, RN, MS, CIC, Assistant Chief Communicable Disease Control Epidemiology and Immunization Section Public Health – Seattle and King County & Mark W. Oberle, MD, MPH, Professor & Associate Dean School of Public Health & Community Medicine University of Washington This evaluation research was supported by the University of Washington School of Nursing, Dean’s Excellence in Nursing award to the first author. 2 We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of L. Clark Johnson, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor of Psychosocial Community Health for his significant contributions as data analyst. 1 Page 1 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Abstract On January 24, 2002 the Washington State Department of Health (DOH), in collaboration with local and federal agencies, conducted an exercise of the CDC’s National Pharmaceutical Stockpile (NPS) dispensing portion of the Washington State plan. This exercise included predrill planning, training and the orchestration of services of 40+ dispensary site workers. These workers provided education and post exposure prophylaxis for over 230 patient volunteers in the aftermath of a simulated exposure to B. anthracis. This article discusses findings of a post-drill questionnaire completed by 90% of these dispensary site workers who provided triage, education, dispensary, security and other services during this exercise. In general, this dispensing drill promoted confidence in the worker participants and provided an opportunity for these participants to coordinate their activities. This mock bioterrorist preparedness exercise allowed worker participants and observers to review and evaluate the Washington State plan for dispensing the NPS. This paper is apparently the first published account of dispensary site worker’s subjective impressions and quantitative analysis of their post-drill opinions following a simulated bioterrorist post exposure chemoprophylaxis dispensing exercise. Key words: Medication dispensing Center, bioterrorist event, National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Page 2 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Introduction / Overview In the aftermath of the anthrax attacks on the Eastern Seaboard of the US in the fall of 2001, public health authorities advised more than 30,000 individuals who may have been exposed to anthrax spores to take oral antibiotics [1]. Medication dispensing centers were set up in the affected metropolitan areas to triage and provide prophylaxis for individuals potentially exposed to this bioterrorist agent [2]. Although the Department of Health and Human Services now requires all states receiving federal bioterrorism funding to have plans “to receive and distribute critical stockpile items and manage a mass distribution of . . . antibiotics . . .” in the aftermath of a widespread bioterrorist attack, there has been very little research to date on how these dispensing centers should be designed, staffed or operated [3]. The goal of this research article is to describe and discuss selected outcomes from a large scale dispensing exercise from the perspective of the participating site workers who screened, triaged and operated the dispensing center in the aftermath of a simulated bioterrorist event. On January 24th, 2002, the Washington State Department of Health (DOH) in collaboration with the Public Health of Seattle, King County, the Seattle Fire Department, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Emergency Preparedness, the University of Washington, Harborview Medical Center, U.S. Department of Defense, the Spokane Regional Health District, the Tacoma – Pierce County Health department and many other local health jurisdictions conducted a demonstration of bioterrorism preparedness, specifically designed to test the dispensing portion of the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile of the Washington State plan. Page 3 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Program The Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) has developed and is charged with overseeing the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Program. The mission of the CDC’s National Pharmaceutical Stockpile program (NPS) is to ensure the availability of life saving pharmaceuticals, antibiotics, chemical interventions, as well as medical supplies, and equipment and their prompt delivery to the site of a disaster, anywhere in the United States. The NPS is available to supplement the initial response to an incident of biological or chemical terrorism. That response will come from local and state emergency, medical and public health personnel. A primary purpose of the NPS is to provide critical drugs and medical material that would otherwise be unavailable to local communities. CDC’s NPS is a unique resource available for immediate deployment to any US location in the aftermath of a biological or chemical terrorist attack directed against a civilian population [4]. Bioterrorism Preparedness: Mass Antibiotic Dispensing Exercise The goal of this bioterrorism preparedness exercise was to demonstrate and test the State of Washington State’s plan for dispensing the NPS. To accomplish this goal necessitated the planning, cooperation and coordination of the activities of personnel from various state, local and federal agencies as well as the orientation and training of the dispensary site workers. The dispensary site worker groups included screeners, triage, educators, security, dispensing staff (including pharmacists and pharmacy technicians) as well as other dispensary site workers who provided ancillary and supportive services. The various duties, tasks and responsibilities of these dispensing site workers conformed to the Washington State’s DOH dispensing site template and Page 4 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings were expressly formulated to provide time sensitive education and post-exposure prophylaxis to large numbers of actual victims of a bioterrorist event or, in the case of this exercise, to volunteer patients in a simulated B. anthracis exposure. Each dispensary site worker group had a specific set of job duties and responsibilities and all dispensary site workers received pre-drill training and/or orientation. More complex than a tabletop exercise [5], this NPS dispensing drill required an extraordinary degree of interagency planning, a facility and the recruitment of human subjects/volunteers. This dispensing drill also entailed the orientation and/or training as well as the coordinated participation of over 40 dispensing site workers, a patient flow scheme and post exposure prophylaxis of hundreds of simulated “anthrax exposed victims”. Part I of this two part series of NPS exercise evaluation reports detailed the volunteer patient outcomes and illustrated the distribution center’s patient flow floor plan [6]. The simulated mass distribution of antibiotics consisted, in most cases, in the dispensing of individual packets of candy representing the emergency rations of antibiotics that would, in all likelihood, be dispensed in the aftermath of a mass exposure to B. anthracis aerosol [1]. The 18 confirmed bioterrorism-related cases of anthrax in New York, New Jersey, Washington DC, Florida and Connecticut in October/November of 2001, illustrated that the “threat” of bioterrorism was real [7, 8]. Guidelines for post exposure prophylaxis to prevent inhalational anthrax following the release of B. anthracis aerosol have been promulgated by the CDC and call for the administration of either ciprofloxacin or doxycycline as first line agents [9]. However, the epidemiological circumstances surrounding a particular B. anthracis aerosol release and ongoing case monitoring are needed to identify high-risk groups and to direct needed Page 5 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings follow-up care [10]. For example, on October 15th, 2001 a staff member opened a letter sent to Senator Daschle in the Hart Senate Office Building. A white powder, which later tested positive for anthrax, was aerosolized upon opening. Staff members in affected offices in the Hart Senate Office Building were evacuated and later offered post exposure antibiotics [11]. The January 24th, 2002 NPS Dispensing Drill: Exposure Scenario An anthrax exposure scenario similar to the October 15th, Hart Senate Office Building exposure was created for the purposes of the NPS dispensing drill. In essence, the NPS drill scenario described a plausible exposure to B. anthracis aerosol and is described in more detail in Beaton et al [6]. Over 230 students, observers and University Staff members volunteered to roleplay a “potentially anthrax exposed” community member seeking antibiotics. Various patient scenarios expressly created for purposes of the exercise are also described in Beaton et al [6]. Dispensary Site Worker Survey Instrument The dispensing site worker survey was designed to assess the dispensing site workers’ appraisals and drill impressions immediately following the exercise. DOH and program personnel felt it was important to survey dispensing site staff immediately post exercise to discern what they felt “went right” and what “needed to be improved” in future drills (or in the event of an actual large scale dispensing or inoculation effort.) The authors also felt it was important to assess the psychosocial impact(s) of the drill process, if any, on the workers participating in the drill. In addition to basic demographic questions (gender and age), worker survey participants were asked to respond to a total of 11 questions. Dispensing site worker survey participants were asked to: Page 6 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings 1. Identify their specific role in the drill, 2. Evaluate the drill site in terms of how well it met their specific needs, 3. Evaluate the adequacy of their pre-drill training, 4. Estimate (in minutes) how long it took for them to “feel comfortable” with their specific drill tasks and duties, 5. Rate the degree to which they felt that they had all of the equipment they needed “to do a good job”, 6. Rate their physical comfort in their dispensary site workspace, 7. Estimate how long (in hours) they could perform their specific drill tasks (uninterrupted) in an effective and safe manner, 8. Report if there were any distractors that interfered with their drill tasks (and if they existed, to identify them), 9. Rate their confidence in their communities’ ability to respond to this type of bioterrorist event in their community, 10. Rate the degree to which they felt this drill affected their perceived confidence in their community’s ability to respond to this type of bioterrorist event in their community, and 11. Rate the degree to which they felt more or less prepared/competent after this drill. Most of these dispensary site worker survey items employed a 0 – 100 visual analogue scale (VAS) and asked respondents to rate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with a specific statement and/or to express their opinion using the VAS and explicit anchors. The VAS is a self-report measure, which can yield a reliable, and a valid measure of a particular subjective experience or opinion [12]. Page 7 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings All dispensary site workers were also asked to provide general and specific written comments and feedback about the dispensing drill, but their qualitative remarks, with a few exceptions, are not presented here. At the completion of the exercise dispensing site workers were given the opportunity to respond to an anonymous “worker” survey. This dispensary site worker survey and their anonymous participation as subjects conformed to the UW Human Subjects Use Board Requirements. DISPENSARY SITE WORKER FINDINGS Sample/Sampling Procedures All dispensing site workers (n = 48) were given the opportunity to complete questionnaires on site immediately following the drill. All dispensary site workers had the training, credentials and/or licensure required to perform their worker specific duties at the exercise. The following findings are based on replies of dispensing site workers who completed questionnaires (n = 43; 90% rate of response) after they had finished their duties. (Survey item n’s ranged from 39 – 43 since some survey items for some respondents were left blank or were unscorable). An equal number of men and women with a mean age of nearly 44 y.o. completed dispensing site worker surveys. Table 1 documents the frequencies and respective percentages of the various dispensing site worker roles reported by the worker survey respondent sample (n = 43). Survey Results Table 2 shows the content and descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for dispensary site workers for survey items #2 - #11. As shown in Table 2, the majority of workers “agreed” to “strongly agreed” with the statements that this dispensing site location met my needs Page 8 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings (item #2), that my “workplace was physically comfortable” (item #6) and that “I had all of the equipment needed to do a good job” (item 5). Regarding the latter, the specific equipment “needed to do a good job” varied widely depending on the worker group, e.g. for the educators it may have included an overhead projector and for security it may have included a portable radio. There was a strong correlation (r = .62; p <.01) between these items #5 & #6 in the dispensary site worker survey participants (n = 41). Also, as shown in Table 2 and in Figure 1, the majority of dispensing workers felt their “training prior to the drill was adequate”; (>60% either “agreed” to “strongly agreed” with item #3). A significant positive correlation existed (r = .40, p <.01) between the worker participants’ perception of a physically comfortable workplace and their subjective ratings of their pre-drill training. Figure 2 depicts the frequency histogram of the time (in minutes) survey respondents felt “it took to feel competent with (their) assigned task” (item #4). The reported times it took dispensary site workers to feel competent ranged from 0 – 30 minutes. However, the mean reported time required for site worker survey participants “to feel competent” after the exercise began was just 11.0 minutes, with a mode of 0 minutes. The majority (75%) of dispensing site workers reportedly felt that it took five minutes or less for them “to feel competent with their assigned tasks”. Figure 3 depicts the frequency histogram of the amount of time (in hours) that the dispensary site worker survey respondents felt that they could continuously perform their (specific) tasks safely and effectively (item #7). Though the mean for the respondents was approximately 6.9 hours, approximately 25% of the workers felt they could work continuously for only four hours or less. Figure 4 depicts results for item #7 by worker group with the corresponding 95% confidence bars. Both education (n = 6) and triage (n = 5) worker groups Page 9 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings reported that they would continuously work safely and effectively for a significantly fewer number of hours (mean 4 hours) compared to the security (n = 5) worker group (Scheffe post hoc test; p’s <.05). Most of the dispensing site workers were somewhat to completely confident (VAS 50 to 100) in the ability of their community to respond to a bioterrorist event like the one simulated in this drill (See Figure 5). However, as shown in Figure 6 the perceived “community confidence” ratings of the educator worker group was statistically lower (self-rated less confident) than that reported by the security site worker group (Post hoc Scheffe test, p <.05). Finally, and importantly, the vast majority of dispensing site worker survey participants reportedly felt their “community/preparedness” to respond to a similar bioterrorist event had been enhanced by their participation in the NPS drill (see Figure 7). There were no differences between the various dispensary site worker groups on this measure of the psychological impact of drill participation. DISCUSSION A 90% rate of participation is generally considered good to excellent for survey samples and strongly suggests that the worker sample was representative of the dispensing site worker population present at the drill [13]. However, comparisons between the various dispensing site “worker role” groups on individual survey items were problematic because of the small numbers of participants in these worker groups and a corresponding lack of statistical power [14]. Most of the dispensing site workers in this investigation agreed that the dispensing site location met their specific needs and that their training prior to the drill was adequate. Though a small minority of dispensing site workers did not feel their pre-drill training had been adequate, most dispensary site workers felt competent to perform their dispensing tasks within minutes Page 10 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings (mean = 11 minutes) after the drill had begun. Most dispensary site drill workers also felt their workspace was comfortable and that they had all of the equipment they needed to do a good job. There was, however, a wide range of estimates (from 2 – 14 hours) as to how long a given dispensing site worker felt they could perform their specific duties continuously, safely and effectively (See Figure 3). Educators and triage workers reported that they could work continuously (safely and effectively) for fewer hours, on average, than other dispensing site workers. This is important since staffing levels at a medication distribution center may be a critical and limiting factor in sustaining a protracted (“24/7”) response for the aftermath of a bioterrorist incident [15]. If this finding is replicated in future drill exercises it suggests some differential scheduling and/or workforce planning considerations for specific dispensing site worker groups. About one third of dispensing site worker reported the presence of “distractors” that interfered with their ability to perform their duties. From a review of their qualitative replies, these reported distractors, primarily were limited to invited site observers, cameras and “noise”. Again, the reported presence of distractors in even a minority of site workers in such a wellplanned and well-controlled exercise is of some concern since distractors could conceivably alter their performance in a medication-dispensing center in the aftermath of an actual bioterrorist attack. Most dispensing site workers were “somewhat” to “completely confident” in the ability of their community to respond to this type of bioterrorist event and most also felt that their participation affected their related confidence to respond to this type of bioterrorist event to “some degree” to “completely”. Importantly, the clear majority (70%+) of dispensing site Page 11 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings participants felt their participation as workers in the exercise enhanced their perception of how prepared/competent they felt their community was to respond to this type of bioterrorist incident. Only a single dispensing site worker participant (out of a total of 43 participants) felt much less confident/competent after the NPS dispensing drill. Clearly, the dispensary site worker survey participants felt that the drill was a process/event that had positively affected their perceptions of how competent/prepared their community was to respond to a similar bioterrorist incident. This important effect of enhanced confidence following a disaster training exercise has been previously identified [16, 17, 18] and may be one of the most important outcomes of such exercises. The Top Officials (TOPOFF) exercise measured federal and state bioterrorism preparedness to a simulated plague attack on the population in and around Denver CO, and included a model antibiotic distribution center [19]. Also, while there have been a few prior reports of mass immunization efforts in the aftermath of actual disease outbreaks [20, 21, 22], and computer modeling of hypothetical antibiotic distribution center based on various bioterrorism response scenarios [15], this is apparently the only report of dispensary site worker’s subjective impressions and a quantitative analysis of their post-drill opinions following a simulated bioterrorist post exposure chemoprophylaxis dispensing exercise. In summary, this mock bioterrorist preparedness disaster exercise allowed participants and observers to evaluate Washington State’s DOH plan for dispensing the NPS. It is important to note that the dispensary site drill workers were the individuals who, in all likelihood, would have been those involved had this been an actual bio-disaster [23]. This dispensing drill promoted confidence in the participants and also offered an opportunity for worker groups and Page 12 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings participants to coordinate their activities [17]. It also allowed drill participants the opportunity to review and evaluate the Washington State plan for dispensing the NPS. Finally, although these dispensary worker findings support the conclusion the drill itself was relatively successful and effective, care should be taken not to embrace a misplaced sense of security [24]. Page 13 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Table 1. Frequency and percentage(s) of worker roles in respondent sample (n = 43) Reported Worker Frequency (n) Percent Cumulative Percent 1 6 6 11 3 5 3 1 7 43 2.3 14.0 14.0 25.6 7.0 11.6 7.0 2.3 16.3 100.00 2.3 16.3 30.2 55.8 62.8 74.4 81.4 83.7 100.0 - Role(s) Operations Educator Triage Dispenser1 Registration Security Router Greeter Other Total 1 Dispensers included both pharmacists and pharmacists’ aides. Page 14 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Table 2. Dispensing Site Worker Survey descriptive statistics for items #2 – #11. Item Item Content Standard Mean Number Deviation 2 The location chosen was well suited to your needs 85.81 13.1 3 The training I received prior to the drill was adequate 70.11 27.6 11.02 10.42 How long did it take to feel competent performing the specific 4 assigned tasks? (in minutes) 5 I had all equipment necessary to do a good job 80.31 22.2 6 I was physically comfortable in my workspace 79.61 20 6.93 3.33 How long (in hours) could you continuously perform your 7 specific drill tasks in a safe and effective manner? Reported distractor (or distractors) that impaired drill 30%4 8 performance (even minimally) How confident do you feel in your community’s ability to 9 64.75 21.3 64.06 26.1 72.37 17.9 respond to this type of bioterrorist incident? Did your participation today’s drill affect your perceived 10 confidence? After today’s drill did you feel your community is more or less 11 prepared/competent to respond to this type of bioterrorist incident? 1 0 = strongly disagree; 25 = disagree; 50 = neither agree nor disagree; 75 = agree; 100 = strongly agree in minutes 3 in hours 4 13/43 survey participants reported a distractor 5 0 = not at all confident; 50 = somewhat confident; 100 = completely confident 6 0 = not at all; 50 = to some degree; 100 = yes, completely 7 0 = much less prepared; 50 = about the same; 100 = much more prepared/competent 2 Page 15 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings References 1. T. Inglesby, T. O’Toole, D. Henderson, J. Bartlett, M. Ascher, E. Eitzen, A. Friedlander, J. Gerberding, J. Hauer, J. Hughes, J. McDade, M. Osterholm, G. Parker, T. Perl, P. Russell, K. & Tonat. Consensus Statement – Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002 Update Recommendations for Management. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287 (17) (2002): 2236-2252. 2. R. Brookmeyer & N. Blades. Prevention of inhalation anthrax in the US outbreak Science, 2002; 295 (5561): 1861. 3. Department of HHS Press release, January 31, 2002: HHS Announces $1.1 Billion in funding to states for bioterrorism preparedness: Below accessed December 19, 2002 from http://www.hhs.gov/news/ (Go to Press releases/2002 Press Releases/January 31, 2002 Press release) 4. CDC NPS Program Website Available at: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/nceh/nps Accessed December 19, 2002 5. T. O”Toole, M. Mair, & T. Inglesby. Shining light on “Dark Winter”. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 34, (2002): 972 – 983. 6. R. Beaton, M. Oberle, V. Wicklund, A. Stevermer & D. Owens (2003). Evaluation of the Washington State National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing Exercise. Part I – Patient Volunteer Findings. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, September Page 16 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings 7. L. Gwerder, R. Beaton, & W. Daniell. Bioterrorism: Implications for the Occupational and Environmental Health Nurse. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal, 49 (11), (2001): 512 – 518. 8. CDC Update: Investigation of bioterrorism – related anthrax and interim guidelines for clinical evaluation of persons with possible anthrax. MMWR, 50 (43), (2001): 941 – 948. 9. CDC Update investigation of anthrax associated with intentional exposure and interim public health guidelines. October 2001, MMWR; 50 (42), 889 – 897. 10. W. Perkins. Public health implications of airborne infection. Bacterial Review. (1961); 25: 347 – 355. 11. A. Anderson, & J. Eisold. Anthrax attack at the United States Capitol Front Line Thoughts. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal, 50 (4), (2002): 170 – 173. 12. A. Gift. Visual analogue scales: measurement of subjective phenomena. Nursing Research, (1989); 38: 286 – 288. 13. L. C. Johnson, R. Beaton, S. Murphy & K. Pike. Sampling bias and other methodological threats to the validity of health survey research. International Journal of Stress Management, 7, (2000), 247 - 268. 14. J. Cohen. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Page 17 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings 15. N. Hupert, A. Mushlin, M. Callahan. Modeling the public health response to bioterrorism: Using discrete event simulation to design antibiotic distribution centers. Medical Decision Making, 2002, Sept – Oct Supplement, s17 – s25. 16. R. Beaton & L. C. Johnson. Evaluation of domestic preparedness training for first responders. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 2002, 17 (2). 17. D. Lehnhof. Planning mass casualty drills. In L. Garcia (Editor): Disaster Nursing: Planning, Assessment and Intervention. Rockville, MD, 1985, Aspen 18. S. Hassmiller. Disaster Management. In M. Staphope and J. L. Lancaster (Editors) Foundations of Community Health Nursing. St. Louis, MO, 2002, Mosby 19. T. V. Inglesby, R. Grossman & T. O’Toole. A plague on your city: Observations from TOPOFF. Clinical Infectious Disease. 2001; 32 (3); 436 – 445. 20. M. T. Osterholm. How to vaccinate 30,000 people in three days: realities of outbreak management. Public Health Reports, 2001; 116 (Supplement 2): 74 - 78. 21. Mass Immunization Campaigns: A “How to” Guide based on experience during the February 2000 Capital Health Meningococcal Immunization Campaign. Alberta, Canada: Capitol Health; 2000. 22. R. Atwood, M. Patnode, & L. Topel. Yakima Health District Meets the Challenge of Meningococcal Epidemic. Washington Public Health, (1991), Winter, 2 – 6. 23. S. L. Berglin. Emergency nurses in Community disaster planning. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 1996, 22: 184 – 189. 24. J. Waeckerle. Disaster planning and response. New England Journal of Medicine, 1991, 324 (12), 815 – 821. Page 18 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Figure Legends Figure 1. Frequency histogram of dispensary site worker ratings of the degree to which they felt the pre-drill training was adequate Figure 2. Frequency histogram of dispensary site worker estimates of the time it took to feel comfortable/competent with their assigned tasks (in minutes). Figure 3. Frequency histogram of dispensary site worker estimates of the amount of time (in hours) they felt they work continuously and perform tasks safely and effectively Figure 4. Mean amount of time (in hours) and 95% confidence intervals dispensary site worker groups felt they could work continuously and perform their duties safely and effectively Figure 5. Frequency histogram of dispensary site workers ratings of their self-reported confidence that their community could respond to a similar bioterrorist incident Figure 6. Mean confidence levels and 95% confidence intervals (in VAS units) of the worker groups that their community could respond to a similar bioterrorist incident. (100 = completely competent; 50 = somewhat confident). Figure 7. Frequency histogram of the dispensary site workers ratings of changes (if any) in their self-reported confidence to respond to a similar bioterrorist incident following and as a result of the drill. Page 19 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig. 1. Count 30 20 10 0 Stongly Disagree Neither Strongly Agree Training Prior to Drill was Adequate Page 20 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 2 12 Count 9 6 3 0 <5 5-<10 10-<15 15-<20 20-<25 >25 Time it took to feel competent w/ assigned tasks (min) Page 21 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 3 Count 12 8 4 0 2-3 4-5 6-7 8-9 10-11 12-13 Continuous Safe / Effective Perform (hrs) Page 22 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 4 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 N= 6 5 11 5 15 Educator Triage Dispenser Security Other Workers Role Page 23 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 5 Count 30 20 10 0 Page 24 of 26 Completely Somewhat Not at All Confident community can respond to bioterrorist incident National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 6 120 100 80 60 40 20 N= 6 5 10 5 16 Educator Triage Dispenser Security Other Worker's Role Page 25 of 26 National Pharmaceutical Stockpile Dispensing: Part II – Dispensary Site Worker Findings Fig 7 Count 30 20 10 0 Much Less No more No Less Much More Following the Drill I am ... Confident Page 26 of 26