The Urban Water balance: a case study at the

advertisement

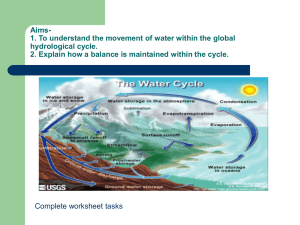

The Urban Water Balance: a case study of the Prinseneiland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands By Paul Rutten Introduction Currently more than half the world population lives in urbanised areas. This means that knowledge about the urban climate becomes increasingly important. The urbanised areas also represent a large economic value, which can be sensitive to damage by water under extreme conditions. In the future these extreme conditions with the consequent damages can become more common because of climate change. When it comes to water, the climate can be best described with the hydrological cycle. The hydrological cycle is used to describe all the significant processes and their interconnections that exist in an (urban) area. Qualitatively, the hydrological cycle of urban areas is well understood. Quantitatively, however, this is different, because most (not all!) previous research focussed on quantifying individual processes in the urban hydrological cycle. Despite the merits of this earlier research, looking only at parts of the hydrological cycle leaves one with an incomplete view. The interconnections and feed-back loops in the cycle of an area remain unknown, while they may actually have the most influence on the processes in the area. The interconnections and feed-back loops can be investigated by describing the entire cycle with a perceptual model. This perceptual model is usually translated into a water balance, which allows one to test hypotheses of the processes in the hydrological cycle by checking whether the balance is closed. The water balance has been frequently used to investigate the hydrological cycle of rural watersheds, which makes it a technique proven to be effective. In this research the water balance and techniques to investigate hydrological processes are used to quantify the hydrological cycle of the Prinseneiland in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Goals The goal of the research is to quantify the processes in the hydrological cycle and close the water balance of the Prinseneiland. To do this key parameters and variables that govern the hydrological cycle are measured or estimated and the entire cycle is modelled with a water balance to test hypotheses of the processes in the area. By doing this our understanding of the hydrological cycle of the city increases. We can also look more closely at which processes are most important. Furthermore, we could change the input of the hydrological cycle and see the effects of climate change without suffering from possible damages. With this information we can determine the sensitivity of our urban areas to water related damage. Site description The Prinseneiland (52° 23' 15" N 4° 53' 15" E) is a fairly small island (about 3.4 ha.), which was created in the seventeenth century by fixing large pieces of dislodged peat in the area to place. The constructed peat island was supplemented with sand and debris to increase the surface level and has been in use by the people of Amsterdam ever since. About 44 % of the island is built-up, 22% is paved and 34 % is unpaved. The buildings consist of two large blocks of former warehouses and other tall buildings in the middle of the island and smaller (groups of) buildings on the sides. The unpaved areas are located on the sides of the island and within the two blocks of buildings in the middle. See the figure below. The Prinseneiland is quite suitable for determining the water balance, because of its relative isolation from its surroundings. Because of it being an island, there is a more or less constant water level around it, acting as a known boundary condition. There is a sewerage pump on the island itself, which only serves the island. On top of that, there was no need to install a drainage system to keep the groundwater levels down, which further reduces complexity. Figure 1. Aerial photograph of the Prinseneiland taken in 2008. Source: Google Maps

![Job description [DOC 33.50 KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007278717_1-f5bcb99f9911acc3aaa12b5630c16859-300x300.png)