ITCOLE- projekti

advertisement

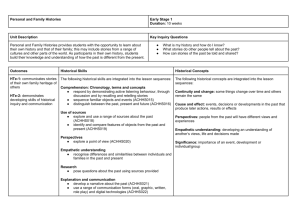

Inquiry Learning, building bridges to practice Workshop May, 29-31, 2006 University of Twente, The Netherlands How to design classroom practices for collaborative inquiry? Minna Lakkala, minna.lakkala@helsinki.fi Centre for Research on Networked Learning and Knowledge Building, Department of Psychology, University of Helsinki, http://www.helsinki.fi/science/networkedlearning Case description: 10 Secrets – Progressive inquiry in history The project was carried out in the Finnish test site during the EU-funded ITOCLE-project (see http://www.euro-cscl.org/site/itcole; Lakkala, Lallimo & Hakkarainen, 2005). The participants were on the 5th grade in a Finnish elementary school, altogether 56 students from two different classes, and two teachers. The project was carried out during nine weeks, in history and Finnish language lessons. The work consisted of 2 to 4 hours per week in a computer lab (with 17 computers), and 2 to 4 hours per week in regular classroom (with one computer) or in the school library (with 12 computers). In Finland students start learning history on the fifth grade; thus, for the participating students this project was the first time to study history. There were three types of learning goals in the project: 1) Goals related to the subject domain, such as becoming acquainted with historical time periods and their characteristics, as well as understanding the meaning of interpretation in history science; 2) Goals related to skill learning, such as becoming acquainted with procedures relevant in the history research or practices of progressive inquiry and information seeking; 3) Cognitive goals, such as the development of historical perspective and sense of time, as well as inquiry approach to learning. The pedagogical model of progressive inquiry The pedagogical approach that was incorporated into the project was based on the model of progressive inquiry (Hakkarainen, 2003; Muukkonen et al., 2005). The students had used the same working method in the previous school year. The model describes the elements of expertlike knowledge practices in a form of a cyclic inquiry process. It relies on cognitive research on education and is closely associated with the knowledge-building approach of Scardamalia and Bereiter (1994) and interrogative model of inquiry introduced by Hintikka (1999). In a progressive inquiry process, the teacher creates a context for inquiry by presenting a multidisciplinary approach to theoretical or real-life phenomena, after which the students start defining their own questions and intuitive working theories about the phenomena. Students’ questions and explanations are shared and evaluated together, which directs the utilization of authoritative information sources and iterative elaboration of subordinate study questions and more advanced theories, explanations and writings. The model is not meant to be followed rigidly, but it offers conceptual tools to understand and take into account the critical elements in accomplishing collaborative knowledge-advancing inquiry (see Figure 1). Figure 1. Elements of progressive inquiry The Web-based learning environment The Web-based learning environment used in the project was FLE3 (http://fle3.uiah.fi). FLE consist of modules, from which the following two were used in the investigated courses: A user’s WebTop (virtual desktop) and a Knowledge Building module (Leinonen et al., 2003). Each user has a personal WebTop where one can store knowledge items, such as documents, files and links, and arrange them in folders. Users in the same course can visit each other’s WebTop and see its content. Also the shared “course folder” for each course is visible in each participant’s WebTop. The Knowledge Building (KB) module provides a shared space, in the form of threaded discourse forums, for sharing and elaborating problem definitions, explanations and theories together by all the participants. The KB discourse is scaffolded and structured by asking a user to categorize each note by choosing a knowledge type (Problem, Working theory, Deepening knowledge, Comment, Metacomment or Summary) for the posting, corresponding to the progressive inquiry model. The idea is based on the similar functionality as in ComputerSupported Intentional Learning Environment (CSILE), developed by Scardamalia and colleagues (1989). The procedure in the 10 Secrets project The main idea of 10 Secrets project was to interpret historical pictures from different time periods to understand history. The context for the project was created by familiarizing the students with some stories and biographies of historical explorers. A video was shown in order to introduce students to the working practices of historians. Further, the principles and working procedures of progressive inquiry were described and discussed at the beginning of the project. The teachers had uploaded, in FLE3, 10 pictures (or “10 secrets”) from different time periods; e.g. a picture of a cave painting or the statues in Easter Island. The students chose one picture for a starting point for their project; their task was to figure out the mystery of the picture. The teachers gave some written guidelines and guiding questions for the students to start their inquiry (e.g., From what time period the picture could be? Who could the people in the picture be?). The students formed small research groups, based on the picture they selected to investigate. Both of the classes had their own course area in FLE3, but all the students were invited in both of the courses. In two groups, there were students from both classes. First, the students created their own explanation of the picture in FLE3’s Knowledge Building area. Then they commented on each other’s explanations, searched for deepening information from books and from the Web, and developed new and more detailed explanations together. Teachers guided the group’s process in the classroom and in the technology-mediated discourse. At the end of the project, the student wrote self-evaluation memos in the course folder in FLE3, according to the guiding questions given by the teacher. The students also wrote historical stories in groups and posted them to the course folder. The last part of the project was a face-toface classroom discussion where the students evaluated the historical stories they had written. References Hakkarainen, K. (2003). Progressive inquiry in a computer-supported biology class. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 40(10), 1072-1088. Hintikka, J. (1999). Inquiry as inquiry: A logic of scientific discovery. Selected papers of Jaakko Hintikka, Volume 5. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Lakkala, M., Lallimo, J. and Hakkarainen, K. (2005a). Teachers’ pedagogical designs for technology-supported collective inquiry: a national case study. Computers & Education 45: 337356. Leinonen, T., Kligyte, G., Toikkanen, T., Pietarila, J., & Dean, P. (2003). Learning with collaborative software – A guide to FLE3. Helsinki: University of Art and Design. Retrieved from http://fle3.uiah.fi/papers/fle3_guide.pdf (May, 12, 2006). Muukkonen, H., Lakkala, M., & Hakkarainen, K. (2005). Technology-mediation and tutoring: how do they shape progressive inquiry discourse? The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(4), 527– 565. Scardamalia, M. and Bereiter, C. (1994). Computer support for knowledge-building communities. Journal of the Learning Sciences 3: 265-283. Scardamalia, M., Bereiter, C., McLean, R.S., Swallow, J. and Woodruff, E. (1989). Computer supported intentional learning environments. Journal of Educational Computing Research 5(1): 51-68. Pedagogical infrastructures Analyse the pedagogical design of the case using the framework of pedagogical infrastructures: Features shaping the technical infrastructure • • • Providing of the technology and technical advice for the members of the learning community. Organizing the use of technology and situations in which the technology is used. The diversity and nature of tools provided. Features shaping the social infrastructure • • • The explicit arrangements to advance and organize students’ collaboration and social interaction. Openness and sharing of the process and outcomes. The integration of face-to-face and technology-mediated activity. Features shaping the epistemological infrastructure • • • • The conception of knowledge that the practices reflect. Explicitness of knowledge-creating inquiry in the process. The role of knowledge sources used in the course. Students’ and teachers’ role in creating and sharing knowledge. Features shaping the cognitive infrastructure • • • • Explicit modelling of the strategies of inquiry. Guidance provided for the students. Methods used to promote metacognitive thinking. Cognitive scaffolding for collaborative inquiry embedded in tools.