Submit Text Example 1: Cats

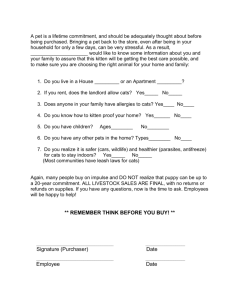

advertisement

Species Description and Current Range This is the familiar house cat. Size and color are highly variable. Weight ranges from about 3-15 kg. The PNW has populations of owned (pet) cats and feral (abandoned, stray or wild-born) cats, which have similar impacts on native wildlife, but different management issues. Pet cats live wherever humans live. Feral cats are concentrated near humans, but also occur in remote areas. Felis and catus are both Latin words meaning cat. Impacts to Communities and Native Species The approximately 77.7 million owned cats and 30-100 million feral cats in the US kill several hundred million birds and about one billion small mammals every year. Researchers at Cornell University estimated that cats kill about $17 billion worth of birds annually in the US, based on spending for birdwatching and hunting. Cats kill some pest mice and rats, but they also kill native mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects and other invertebrates. Endangered or at-risk species that cats have impacted include Least Terns, Piping Plovers, Loggerhead Shrikes, Key West Marsh Rabbits, Brown Pelicans, CA Clapper Rails, Burrowing Owls, Snowy Plovers and Salt-marsh Harvest Mice. Animals that escape after being captured by cats often die later. In WA 17% of animals brought to wildlife rehabilitators were attacked by cats (compared to 2% hit by cars and 1% poisoned). One cat in rural WI killed 1690 animals in 18 months, but 5-365 animals per cat per year is more typical. Both pet and feral cats that are fed continue to kill small animals. Rural cats kill more wildlife than urban cats, but cats kill many birds at feeders in urban/suburban yards. Cats have driven eight bird species extinct on islands worldwide, and have caused the extirpation of over 40 species on New Zealand alone. However, even in continental North America, cats can negatively impact populations of small animals. Much of our native habitat is fragmented into small ‘islands’ surrounded by humans and domestic cats. Humans maintain cats at high densities by protecting them from starvation, disease and predation, which limit numbers of other predators. Cats greatly outnumber all other similar-sized predators combined. Cats are not strictly territorial; they do not exclude other cats from their hunting range. Cats indirectly affect native predators by reducing prey populations. Domestic cats have alternate food sources (from humans) when prey becomes scarce, but native predators do not. Feral cats transmit disease to humans and native animals, including endangered species such as the FL Panther. Control Methods and Management Cats make wonderful pets, but should not be allowed to kill native wildlife. These recommendations save wildlife. 1) Pet cats: Keep your cat indoors. The only way to prevent pet cats from hunting is to keep them indoors. Bells and electronic sonic collars sometimes reduce hunting success, but cannot eliminate predation. Prey species may not associate the sounds with danger and very young animals cannot escape. Some animals such as amphibians cannot hear the sounds. Cats with bells may switch prey species, to animals that do not respond to the tones. Declawing does not always reduce hunting success. Spay or neuter your cats. Outdoor cats can learn to be happy indoors. 2) Feral cats: Never feed stray or feral cats. Do not maintain cat ‘colonies’. Do not leave pet food or garbage where it will attract stray cats. TNR (trap, neuter, release), also called TTVAR, or managed cat colonies, is not the answer for feral cats. People dump cats at colonies, even if dumping is illegal. The food attracts other cats and problem wildlife such as raccoons, skunks and rats, increasing their densities above natural levels. Colony cats that are too wary to be caught are not neutered or spayed. Colony cats do not exclude other cats; colonies may grow to hundreds of cats. Colony cats kill wildlife, even if well fed. Colonies spread disease to humans and wildlife. Cat colonies do not form without an artificial food source. Do not feed feral cats. 3) Protect native wildlife in your yard. Do not locate bird feeders close to cover, where cats can hide to ambush birds. Stop feeding birds if they are being killed by cats. Put animal guards on trees to prevent cats from reaching bird nests. 4) Protect native wildlife on farms. Do not keep more cats than are necessary to control rodents. Neutered well-fed females will stay closer to buildings where rodent control is needed. Traps or rodent-proof storage or construction may be more effective than cats in controlling rodents. Life History and Species Overview Domestic cats reproduce at 7-12 months old. Cats have 1 to 2 litters per year with a gestation period of 63-65 days. Feral cats seldom live longer than 4-5 years while 15-17 years is typical for pet cats. Adult cats eat 5-8% of their body weight per day, but females nursing kittens can eat 20% of their body weight daily. Cats can kill and eat animals as large as they are. Feral cats use a variety of habitats including rock outcrops, burrows, trees, shrubs, culverts, abandoned buildings and farm outbuildings. They are generally opportunistic in habitat and diet. Home ranges of cats in rural areas can be as large as 4 km. History of Invasiveness The domestic cat evolved from wild cats of Europe and Africa. Mediterranean peoples may have kept cats as early as 6000 years ago. Cats were sacred in ancient Egypt, where it was a capital offense to kill a cat, even by accident. It was also illegal to export cats. Special agents traveled around neighboring countries to buy and repatriate cats that had been illegally exported. In spite of this, domestic cats had spread around the Mediterranean by 500 BCE and throughout Europe and Asia by the 10th century CE. People transported cats on board ships, as the spread of some color mutations followed shipping routes. Early colonists brought cats to North America from Europe.