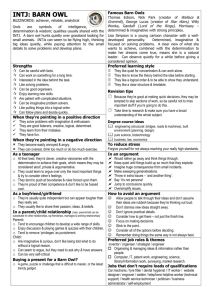

Tyto alba barn owl (lechuza de granero)

advertisement

Tyto alba barn owl (lechuza de granero) By Kathleen Bachynski Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Subphylum: Vertebrata Class: Aves Order: Strigiformes Family: Tytonidae Genus: Tyto Species: Tyto alba Geographic Range Barn owls are the most widespread of all owl species, and are found on every continent except Antarctica. In the Americas, barn owls occur in suitable habitat throughout South and Central America, and in North America as far north as the northern United States and southwestern British Columbia. In Europe, barn owls range from southern Spain to southern Sweden and east to Russia. They are also found throughout Africa, across central and southern Asia, and throughout Australia. Barn owls have been introduced to some oceanic islands to control rodent pests. Habitat Barn owls occupy a vast range of habitats from rural to urban. They are generally found at low elevations in open habitats, such as grasslands, deserts, marshes and agricultural fields. They require cavities for nesting, such as hollow trees, cavities in cliffs and riverbanks, nest boxes, caves, church steeples, barn lofts, and hay stacks. The availability of appropriate nesting cavities often limits use of suitable foraging habitat. (Marti, 1992) Physical Description Mass 430 to 620 g; avg. 525 g (15.14 to 21.82 oz; avg. 18.48 oz) Length 32 to 40 cm (12.6 to 15.75 in) Wingspan 107 to 110 cm (42.13 to 43.31 in) 1 Barn owls are medium-sized owls with long legs that are sparsely feathered down to their grey toes. The head is large and rounded without ear tufts. Barn owls have rounded wings and a short tail that is covered with white or light brown, downy feathers. The back and head of the bird are a light brown with variable black and white spots, while the underside is a grayish white. Barn owls are very striking in appearance. Females tend to be larger, weighing around 570 grams, while males weigh around 470 grams. Females also have a slightly longer body length (34 to 40 cm for females, 32 to 38 cm for males) and wingspan. Wingspan of males and females ranges from 107 to 110 cm. Up to 35 subspecies of Tyto alba are recognized based on differences in body size and coloration. ("The Owl Pages", 2003; Marti, 1992) Reproduction Breeding interval Barn owls breed once yearly; somtimes two or even three broods per year are produced. Breeding season Barn owls breed essentially any time of the year, depending upon food supply. Eggs per season 2 to 18; avg. 5.50 Time to hatching 29 to 34 days Time to fledging 50 to 70 days; avg. 64.30 days Time to independence 3 to 5 weeks Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 1 years (average) Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 1 years (average) Barn owls are most commonly monogamous, although several reports of polygyny exist. Pairs typically remain together as long as both individuals live. Courtship begins with display flights by males which are accompanied by advertising calls and chasing the female. During the chase, both the male and the female screech. The male will also hover with feet dangling in front of the perched female for several seconds; these are known as moth flights. Copulation occurs every few minutes during the nest site search. Both sexes crouch down in front of each other to solicit copulation. The male mounts the female, grasps her neck, and balances with spread wings. Copulation continues with decreasing frequency throughout incubation and chick rearing. 2 Barn owls breed once per year. They can breed almost any time of the year, depending upon food supply. Most individuals begin breeding at 1 year old. Due to the short life span of barn owls (2 years on average), most individuals breed only once or twice. Barn owls usually raise one brood per year, though some pairs have been observed raising up to three broods in one year Barn owl pairs often use an old nest that has been occupied for decades rather than building a new one. The female usually lines the nest with shredded pellets. She lays 2 to 18 eggs (usually 4 to 7) at a rate of one egg every 2 to 3 days. The female incubates the eggs for 29 to 34 days. The altricial chicks are brooded and fed by the female for about 25 days after hatching. They leave the nest on their first flight 50 to 70 days after hatching, but return to the nest to roost for 7 to 8 weeks. The chicks usually become independent from the parents 3 to 5 weeks after they begin flying. ("The Owl Pages", 2003; Marti, 1992) Female barn owls leave the nest during incubation only briefly and at long intervals. During this time, the male feeds the incubating female. All brooding is done by the female, beginning immediately after hatching and lasting until the oldest young is about 25 days old. Males bring food to the nest for the female and chicks, but only the female feeds the young, initially tearing the food into small pieces. The female also eats the feces of the chicks for the first few weeks after hatching in order to sanitize the nest. The parents continue to feed the chicks for up to 5 weeks after fledging. (Marti, 1992) Lifespan/Longevity Extreme lifespan (wild) 34 years (high) Average lifespan (wild) 20.90 months Average lifespan (captivity) 17.90 years [External Source: AnAge] Most barn owls have a relatively short life span. Many only survive one breeding season and the mortality rate may be as high as 75% in the first year of life. in one study, the mean age at death for 572 banded birds was 20.9 months. However, the longest recorded lifespan of a wild barn owl is 34 years. (Marti, 1992) Behavior Barn owls are solitary, or found in pairs. They are nocturnal, and roost during the day in tree cavities, cliff crevices, riverbanks, barns, nest boxes, churches steeples, and other man-made structures. Barn owls are very efficient hunters. It is suspected that they spend much of their time loafing. Most barn owls are sedentary, though some individuals in the northern part of the range are migratory. (Marti, 1992) 3 Home Range In a study of barn owls in New Jersey, the average home range was 7.17 square kilometers. (Marti, 1992) Communication and Perception Barn owls communicate with vocalizations and physical displays. Owlets still in the nest utter several distinct vocalizations, including a twitter used to express discomfort, attention-seeking, and when quarreling with nestmates. Young also give a raspy snoring food call. Adults use a variety of vocalizations, including the advertising call, a drawnout gargling scream that is probably the best known call. The distress call is a series of drawn-out screams. Other vocalizations include a defensive hissing sound, a fast, often prolonged, twitter for feeding, and an explosive yell that is usually directed at a mammalian predator. Also, greeting and conversational twitters seem to convey recognition of mate and accompany various courtship activities. Barn owls are much less vocal when not breeding. The ability of barn owls to locate prey by sound is the most accurate of any animal tested. This very acute sense of hearing allows barn owls to capture prey hidden by vegetation or snow. Their amazing ability to locate prey using sound is aided by their asymmetrically placed ears. This asymmetry allows these owls to better localize sounds generated by prey. Their ears are extremely sensitive and can be closed by small feathered flaps if the noise level is too disturbing. Barn owls also have excellent lowlight vision. Food Habits Barn owls are nocturnal predators that prefer small mammals such as mice, voles, shrews, rats, muskrats, hares and rabbits. They may also prey on small birds. Barn owls begin hunting alone after sunset. As an aid for detecting movement in grassland, they have developed highly sensitive low-light vision. When hunting in complete darkness, however, the owl relies on its acute hearing to capture prey. Barn owls are the most accurate birds at locating prey by sound. Another trait that adds to their hunting success is their downy feathers, which help to muffle the sound of their movement. An owl can approach its prey virtually undetected. Barn owls attack their prey in low flights (1.5m4.5 meters above the ground), capture the prey with their feet, and nip through the back of the skull with the bill. They then swallow the prey whole. Barn owls do cache extra food, especially during the breeding season. (Marti, 1992) Predation Known predators stoats (Mustela) snakes (Serpentes) golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) red kites (Milvus milvus) northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis) common buzzards (Buteo buteo) peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) 4 lanners (Falco biarmicus) Eurasian eagle-owls (Bubo bubo) tawny owls (Strix aluco) great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) Barn owls have few predators. Nestlings are occasionally taken by stoats and snakes. There is also some evidence that great horned owls occasionally prey upon adult barn owls. Barn owl subspecies in the western Palearctic are much smaller than those in North America. These subspecies are sometimes preyed upon by golden eagles, red kites, goshawks, buzzards, peregrine falcons, lanners, eagle owls and tawny owls. When facing an intruder, barn owls spread their wings and tilt them so that their dorsal surface is towards the intruder. They then sway their head back and forth. This threat display is accompanied with hissing and billsnaps that are given with the eyes squinted. If the intruder persists, the owl falls on its back and strikes with its feet. (Marti, 1992) Ecosystem Roles Barn owls limit populations of the mammal and bird species that they prey upon. They also serve as food for those species that prey upon them. Barn owls are host to several parasites. Nestlings are commonly infested with the dipteran Carnus hemapterus. They also host several protozoan blood and intestinal parasites and two species of lice (Kirodaia subpachygaster and Strigiphilus aitkeir). (Marti, 1992) Economic Importance for Humans: Negative There are no negative impacts of barn owls on humans. Economic Importance for Humans: Positive Barn owls limit rodent pest populations, benefiting farmers and others. Ways that people benefit from these animals: controls pest population. Conservation Status IUCN Red List: Least Concern. US Migratory Bird Act: Protected. US Federal List: No special status. CITES: Appendix II. 5 Barn owls are protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act and under CITES Appendix II. They are not federally threatened or endangered in the United States, but they are protected in some individual U.S. states--including Michigan, where they are considered endangered. Threats to barn owl population include climatic changes, pesticides, and changing agricultural techniques. A change of the climate in northern regions is causing snow to last for longer periods, making winter survival difficult for the species. Unlike other birds, barn owls do not store extra fat in their body as a reserve for harsh winter weather. As a result, many owls die during freezing weather or are too weak to breed in the following spring. Pesticides have also contributed to declines in this species. For unknown reasons, barn owls suffer more severe effects from consuming pesticides than other species of owls. These pesticides are often responsible for eggshell thinning in females. Another major factor limiting population growth is modern agricultural methods. Traditional farms with many small structures favored barn owl populations. In modern farms, there is no longer an adequate amount of farm structures for nesting, and farm land can no longer support a sufficient population of rodents to feed a barn owl pair. The barn owl population, however, is declining only in some localities, not throughout the range. (Marti, 1992) Contributors Kathleen Bachynski (author), University of Michigan. Tanya Dewey (editor), Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Kari Kirschbaum (editor), Animal Diversity Web Staff. Marie S. Harris (author), University of Michigan. References Perrins, Christopher, M.. et. al., The Encyclopedia of Birds. Facts on File Publications, 1985. 2003. "The Owl Pages" (On-line). Accessed January 26, 2004 at http://www.owlpages.com/species/tyto/alba/Default.htm. Marti, C. 1992. Barn Owl. Pp. 1-15 in A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, F. Gill, eds. The Birds of North America, Vol. 1. Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington DC: The American Ornithologists' Union. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 6