Pediatric Sedation Newsletter – New Year 2003

advertisement

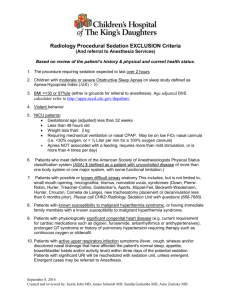

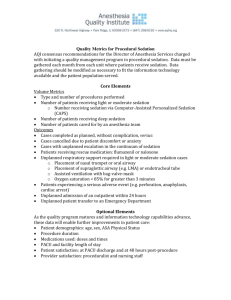

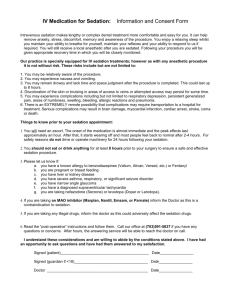

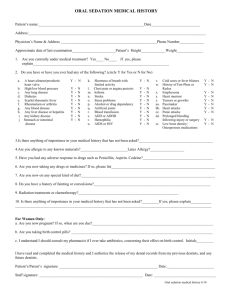

Pediatric Sedation Newsletter – New Year 2003 Departments of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH Editors: Joseph Cravero MD (joseph.cravero@hitchcock.org), George Blike MD george.blike@hitchcock.org Website = http://an.hitchcock.org/PediSedation/ Circulation 3053 Happy New Year. To start things off this year we thought we would reprint a statement addendum from the AAP initially printed in Pediatrics in Oct 2002. For those of you who did not see it at the time, this is an addendum to the 1992 statement on sedation guidelines. It is intended to clarify issues that have been misinterpreted since the original printing of the guidelines. We recognize that most of those who read this newsletter are well aware of the recommendations contained in this statement. However, we believe that this document is well thought out and clearly presented (and represents the policy of a major multispecialty national organization advocating for children’s health) - therefore deserves reprinting in this email format for anyone who may not have seen it or would like to refer to it. This statement and all other policy statements are available at the website AAP.org. Guidelines for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures: Addendum American Academy of Pediatrics - Committee on Drugs Pediatrics, Volume 110,Num4, October 2002, pp 836-838 INTRODUCTION In 1992, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs (COD) published a revision of the policy statement, "Guidelines for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures." 1 Subsequently, the statement had been reaffirmed in 1995 and 1998. Sedation-related accidents continue to occur.2-4 This addendum to the 1992 statement is meant to clarify some of the terms used in that document and to more thoroughly delineate the responsibilities of the practitioner when sedating children. Regardless of the intended level of sedation or route of administration of sedative, sedation of a patient represents a continuum and may result in loss of the patient's protective reflexes; a pediatric patient may move easily from a level of light sedation to obtundation.1 The COD continues to emphasize that sedation of children is different from sedation of adults. Sedatives are generally administered to gain the cooperation of the child. The ability of the child to cooperate depends on chronologic and developmental age. Often, children younger than 6 years and those with developmental delays require deep levels of sedation to gain their cooperation. Children in this age group are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of sedatives on respiratory drive, patency of the airway, and protective reflexes.2,3 Because deep sedation may occur after administration of sedatives in any child, the practitioner must have the skills and equipment necessary to safely manage patients who are sedated. This addendum reaffirms the following principles for the sedation of children: 1. 2. 3. 4. The patient must undergo a documented presedation medical evaluation, including a focused airway examination. There should be an appropriate interval of fasting before sedation. Children should not receive sedative or anxiolytic medications without supervision by skilled medical personnel (ie, medication should not be administered at home or by a technician without medical supervision*). Sedative and anxiolytic medications should only be administered by or in the presence of individuals skilled in airway management and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. 5. 6. 7. 8. Age- and size-appropriate equipment and appropriate medications to sustain life should be checked before sedation and be immediately available. All patients sedated for a procedure must be continuously monitored with pulse oximetry. An individual must be specifically assigned to monitor the patient's cardiorespiratory status during and after the procedure; for deeply sedated patients, that individual should have no other responsibilities and should record vital signs at least every 5 minutes. Specific discharge criteria must be used. The term "conscious sedation" is confusing and, as used in the 1992 statement, 1 has been misinterpreted as a state in which the patient retains only reflex withdrawal to pain. 5 In the 1992 statement, conscious sedation was defined as a state of sedation that "permits appropriate response by the patient to physical stimulation or verbal command, eg, 'open your eyes.'" The minimal responses of reflex withdrawal (a spinal reflex) or moaning in response to a needle insertion are not consistent with this definition of conscious sedation. The intention of the COD was to define "conscious sedation" as a very minimal state of sedation in which the patient would make an appropriate response to a painful stimulus, such as crying, saying "ouch," or pushing away the offending stimulus. In older children, an appropriate response implies that the patient retains the capability to interact with the patient care team. Purely reflexive activity, such as the gag reflex, simple withdrawal from pain, or making inarticulate noises, does not constitute an appropriate response for the purpose of this definition. A sedated child who displays only reflex activity of this sort is in a state of deep sedation, not a state of conscious sedation. The COD recommends that it is more appropriate to recognize the most current terminology of the American Society of Anesthesiologists 6 and replacement of the term "conscious sedation" with "moderate sedation." The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has adopted revisions to its anesthesia care standards 7 consistent with the American Society of Anesthesiologists standards, and the COD recommends that the Academy adopt the same language. "Mild sedation" is equivalent to anxiolysis; "moderate sedation" is equivalent to the previously used term "conscious sedation" or "sedation/analgesia." 8,9 In the 1992 statement, the COD defined deep sedation as "a medically controlled state of depressed consciousness or unconsciousness from which the patient is not easily aroused. Deep sedation may be accompanied by a partial or complete loss of protective reflexes, including the inability to maintain a patent airway independently and to respond purposefully to physical stimulation or verbal command." The COD stated, "Deep sedation and general anesthesia are virtually inseparable for purposes of monitoring." The guidelines stipulated that these levels of sedation require support personnel whose only responsibility is to monitor the patient (ie, this person should not be assisting with the procedure). In addition, a time-based record of vital signs to allow tracking of trends every 5 minutes was recommended. Another area of confusion relates to the location in which the guidelines should be applied. Regardless of the medications selected or the route of administration (oral, rectal, nasal, intramuscular, intravenous, inhalation), the potential for serious adverse effects exists.3 Therefore, the skills of the practitioner and the availability of age- and size-appropriate equipment, medications, and monitoring are most important in rescuing the child should an adverse sedation event occur. The COD has concluded that the guidelines apply in all locations and to all practitioners who care for children. At the time the original statement was published, most children sedated for a procedure received sedatives in a hospital. At present, many children receive sedatives in nonhospital facilities, where the guidelines are not always followed. This is unfortunate, because it is in the nonhospital environment that skilled rescue teams may be least accessible in an emergency. Recent information confirms that adverse sedation events that occur in a practitioner's office are more likely to be fatal than events that occur in a hospital or hospital-like setting.2 Deaths have also occurred when the sedative or anxiolytic medication (even when administered at recommended doses) was administered at home before a procedure.3 Proper recovery procedures (including strict discharge criteria) in particular are important, because some patients may become more deeply sedated after the stimulus of the procedure is discontinued, whereas others will have prolonged sedation effects because of the pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic profile of the medications chosen for sedation or anxiolysis (eg, chloral hydrate, pentobarbital, chlorpromazine). The systematic approach to sedation was intended to provide a uniform guideline for appropriately observing and caring for children requiring sedation for a procedure regardless of where the procedure was performed (office, free-standing medical facility, or hospital). The COD wishes to emphasize the following recommendations: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. The "Guidelines for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures" apply regardless of the settings in which sedatives are administered or the specific training or profession of the practitioners involved. Sedative or anxiolytic medications should not be administered at home as part of a preprocedural sedation plan. Sedative or anxiolytic medications should not be administered by anyone who is not medically skilled or supervised by skilled medical personnel. When children are deeply sedated, at least 1 individual must be present who is trained in, and capable of, providing pediatric basic life support, and who is skilled in airway management and cardiopulmonary resuscitation; training in pediatric advanced life support is strongly encouraged. It is crucial that age- and size-appropriate resuscitation equipment and medications be immediately available. Children who receive sedative medication with a long half-life may require extended observation. On occasion, on the basis of careful, documented review of the medical history, physical examination, and proposed procedure, a practitioner may determine that a hospital is the only appropriate venue for administering sedatives. Third-party payers should respect medical decisions that conform to these guidelines and provide the level of care most appropriate for the patient. COMMITTEE ON DRUGS, 2001-2002: Richard Gorman, MD, Chairperson, Brian A. Bates, MD,William E. Benitz, MD, David J. Burchfield, MD, John C. Ring, MD, Richard P. Walls, MD, PhD, Philip D. Walson, MD LIAISONS : John Alexander, MD Food and Drug Administration ,Donald R. Bennett, MD, PhD American Medical Association ,Owen R. Hagino, MD American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Doreen Matsui, MD Canadian Paediatric Society, Laura E. Riley, MD American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, George P. Giacoia, MD National Institutes of Health ,*Charles J. Coté, MD Liaison from AAP Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Management *Lead author REFERENCES 1. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Drugs. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pediatrics. 1992;89:1110-1115 2. Coté CJ, Notterman DA, Karl HW, Weinberg JA, McClosky C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: a critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:805-814 3. Coté CJ, Karl HW, Notterman DA, Weinberg JA, McCloskey C. Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: analysis of medications used for sedation. Pediatrics. 2000;106:633-644 4. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000 5. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy statement on the use of deep sedation and general anesthesia in the pediatric dental office. In: Reference Manual 1999-2000. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 1999:31. Available at: http://www.aapd.org. Accessed May 25, 2000 6. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Continuum of depth of sedation: definition of general anesthesia and levels of sedation/analgesia. Available at: http://www.asahq.org/standards/20.htm. Accessed February 13, 2001 7. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Standards and intents for sedation and anesthesia care. In: Revisions to Anesthesia Care Standards, Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 2001. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/standard/aneshap.html. Accessed February 13, 2001 8. American Society of Anesthesiologists, Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by NonAnesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:459-471 9. American Society of Anesthesiologists, Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by NonAnesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017 * The term "medical supervision" refers to supervision by a practitioner who, by virtue of training, education, certification, or applicable licensure, law, or regulation, is qualified to supervise the delivery of medical care. The individual may be a physician, nurse, dentist, or other appropriately trained health professional. Commentary: Most of the content in these guidelines is well-accepted at this point. A few issues will engender discussion: 1. We are aware that emergency medicine physicians have questioned the application of “appropriate” NPO guidelines in their setting. How does one judge “appropriate” time intervals (what is safe) when a child is in pain and the evidence on aspiration injury in this setting is sparse at best. We can not pretend to offer answers to this quandary, but recognize that this is an area of ongoing controversy for which more discussion is needed (along with some prospective data). 2. The repeated warning against the administration of “anxiolytics” at home or in the absence of a trained sedation provider conflicts with the growing trend by some neurologists to prescribe rectal valium for home use in children with certain types of seizure problems (e.g.Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 41(5):340-43, 1999). In this particular situation the administration of valium has to be weighed against the risk of a prolonged seizure. The addendum is also at odds with reports published in Pediatrics in the last year concerning the use of chloral hydrate for EEG sedation in an unmonitored setting (Olson DM, Sheehan MG, Thompson W, Hall PT, Hahn J. Sedation of children for electroencephalograms. Pediatrics 2001;108(1):163-5). Comments from the neurologists who read this newsletter are welcome. 3. Pulse oximetry monitoring is emphasized as a key monitor in this addendum. At this point we feel that ventilatory monitoring is almost as useful and recommend it for all patients who receive moderate or deep sedation/anesthesia. Portable, inexpensive, end tidal CO2 monitors and other technologies (? precordial stethescopes) are increasingly being recognized as a standard for deep sedation monitoring for children. We expect that this will be emphasized when the guidelines from the AAP and other professional organizations are fully revised in the near future. Finally, the last point of emphasis in this document concerning third party participation in sedation care will be critical for the future of pediatric sedation practice. As sedation providers we will need to organize and advocate for consistent and appropriate reimbursement for sedation provision if the professionalism and safety of this field of practice is to continue to improve. As always bring on the comments and questions!!! Literature Reviews: Is propofol safe for procedural sedation in children? A prospective evaluation of propofol versus ketamine in pediatric critical care. Vardi A, Salem Y, Padeh S, Paret G, Barzilay Z. Critical Care Medicine. 30(6):1231-6, 2002 Jun. Abstract Summuary: The authors compared propofol with ketamine sedation delivered by pediatric intensivists during painful procedures in the pediatric critical care department (PCCD). The study took place over a 15-month period in an18-bed multidisciplinary, university-affiliated PCCD. All children were randomized to the propofol or ketamine protocol according to prescheduled procedure dates. Propofol was delivered by continuous infusion after a loading bolus dose and a minidose of lidocaine (PL). Ketamine was given as a bolus injection together with midazolam and fentanyl (KMF). Repeated bolus doses of both drugs were given to achieve the desired level of anesthesia. The studied variables included procedures performed, anesthetic drug doses, procedure and recovery durations, and side effect occurrence. The patient's parents, PCCD nurse and resident physician, pediatric intensivist, and the physician performing the procedure graded the adequacy of anesthesia. Of the 105 procedures in 98 children, PL sedation was used in 58 procedures, and KMF was used in 47. Recovery time was 23 minutes for PL and 50 minutes for KMF, and total PCCD monitoring was 43 minutes for PL and 70 minutes for KMF. Five children (10.6%) in the KMF group and none in the PL group experienced discomfort during emergence from sedation. Transient decreases in blood pressure, partial airway obstruction, and apnea were more frequent in the PL than in the KMF sedation. All procedures were successfully completed, and no child recalled undergoing the procedure. The overall sedation adequacy score was 97% for PL and 92% for KMF (p <.05). Conclusions: Both PL and KMF anesthesia are effective in optimizing comfort in children undergoing painful procedures. PL scored better by all evaluators, recovery from PL anesthesia after procedural sedation was more rapid, total PCCD stay was shorter with PL, and emergence from PL was smoother than with KMF. Because transient respiratory depression and hypotension are associated with PL, it is considered safe only in a monitored environment (e.g., a PCCD). Commentary: We could not resist reviewing this article since propofol is becoming increasingly popular in intensive care units and emergency departments across the country. There are so many interesting points to make – we will focus on just a few. The title of the article hinted at a safety evaluation of propofol (in general) for procedural sedation, but what we find is a small cohort comparison of propofol to a ketamine combination for procedures in an ICU. We would like to begin by considering the terminology used in this paper, which we find somewhat confusing. The authors introduce this study by quoting the definition of “procedural sedation” from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) “A technique of administering sedatives of dissociative agents with or without analgesics to induce a state that allows the patient to tolerate unpleasant procedures while maintaining cardiorespiratory function”. The end of this quote includes the statement “Procedural sedation and analgesia are intended to result in a depressed level of consciousness but one that allows the patient to maintain airway control independently and continuously. Specifically drugs, doses, and techniques used are not likely to produce a loss of protective airway reflexes”. They then go on to describe their comparison of two techniques which utilize combinations of medications where airway loss and apnea may well be expected. (proven by their results!) The authors conclude their introduction by stating that the combination of ketamine with midazolam and fentanyl has a “well documented record of safety in children”, but cite no supporting literature. One might ask how well this safety is documented – in what setting, by which providers, for which procedures? The specifics of this study are important. The propofol protocol for this study involves a mini dose of lidocaine followed by 2.5-3.0 mg/kg bolus and then a 200 a mcg/kg/min infusion. This dosing regimen results in a state best described as deep sedation or anesthesia. Similarly the combination of intravenous 0.1 mg/kg midazolam with 2mcg/kg fentanyl and 2mg/kg ketamine in rapid sequence as described in this paper is (for all intents and purposes) anesthesia. We find the use of the phrase “procedural sedation” confusing and inconsistent with the accepted terminology used by the AAP, ASA, AAPD, and the JCAHO. Perhaps even more importantly the combinations used in this paper do not conform to the definition of procedural sedation as defined by ACEP. These distinctions are important, as most experts would agree that there is some gradation of the intensity of monitoring and expertise involved in sedation when we move from states that involve minimal impairment of consciousness to ones that may completely obliterate response to stimulation. Classifying all depths of sedation given for procedures in one category ignores the fact there is a difference between these states. A more accurate title (and a more interesting study) might be “Is deep sedation/anesthesia with propofol or ketamine/midazolam/fentanyl (in the PICU) safe for procedures in children?” There are several methodological difficulties with this study: 1. Several scoring systems were used to judge the adequacy of the sedation for painful procedures. Some of these scoring systems were validated scoring systems – several were not. 2. Individuals subjectively judging the adequacy of sedation were not blinded to technique. 3. Randomization was done simply by the month in which the procedure was performed. 4. This paper includes subjective ratings from parents and others concerning the performance of the sedation and this is always a concern. These types of rating scales are heavily influenced by previous experience. For instance if your child had a previous procedure with no sedation or distraction, any subsequent effort to provide sedation would be rated very highly. No data on previous experience is presented in this paper. Note: The authors describe a 10% incidence of “pain” on emergence from the ketamine combination and 0% in the propofol group. Their scoring system is identifying the common emergence reactions seen in this patient group – not related to pain but rather behavioral effects of the medications. There would be no reason for ketamine patients to have more pain than propofol patients. Safety-related data from this study included the fact that 12 of 58 patients in the propofol group required intervention to keep a patent airway and 10 required positive pressure ventilation due to apnea. Three such instances occurred in the 47 individuals in the ketamine group and one of these patients required intubation because of respiratory depression and difficult ventilation. The authors conclude that propofol administration by intensivists is safe. As always, we would like to point out that this may be true but this study is completely underpowered to make this statement given the expected incidence of critical events in this practice. The number of significant respiratory events leads us to agree with the authors that only those individuals who are well trained and completely confident in the management of pediatric airways should be using these medications in this manner. We must also consider that the frequency of these events represents a surrogate marker that this practice may not be completely safe – i.e. what would we find if we looked at 3,000 of these sedations? It should be noted that the choice of a relatively high dose, pure propofol technique for painful procedures is not ideal. Propofol has no intrinsic analgesic properties and patients may move when stimulated in spite of large doses that are associated with airway obstruction (see above study results). Finally, we recognize that propofol is being used by a variety of providers and its use will continue to grow. On the other hand, everyone who uses this drug understands that its advantages come at the price of a small therapeutic index with respect to airway compromise. In addition to the comparison studies reviewed here, reports of its use in large populations should be submitted. Data on how different providers with different training and backgrounds handle the respiratory effects of this drug are critical. Detailed accounts of experiences – positive and negative – are needed so that the community of providers who deliver sedation to children can formulate sensible policies concerning the use of propofol in the future. We look forward to your feedback and opinions on this matter. In the course of our work with children having procedures we are often asked to place IV’s or perform venipuncture on children who are awake. Two recent studies have compared medications for topical anesthesia. We will not fully review them, but rather present a brief synopsis. A clinical study to evaluate the efficacy of ELA-Max (4% liposomal lidocaine) as compared with eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream for pain reduction of venipuncture in children. Eichenfield LF, Funk A, Fallon-Friedlander S, Cunningham BB. Pediatrics 2002;109:1093-1099. This paper compared EMLA to ELA-Max in 120 patients and found equal effectiveness for venipuncture when ELA-Max is applied for 30 minutes vs. EMLA applied for 1 hour. ELA-Max does not require an occlusive dressing and does not contain prilocaine – eliminating the risk of methemoglobinemia. The more rapid onset of ELA-Max may present some advantages. Notably this study was not performed with drug company support. Lidocaine iontophoresis versus eutectic mixture of local anesthetics for IV placement in children. Galinkin JL, Rose JB, Harris K, Watcha MF. Anesth Analg 2002;94:14848 In this study 26 patients undergoing multiple IV placements were enrolled in a prospective crossover study comparing lidocaine iontopheresis vs EMLA. The medications were equally effective when evaluated using a standard pain score. Interestingly when the children were allowed to choose which technique they would preferred after experiencing both, the majority chose lidocaine iontopheresis (50%) vs. EMLA (23%). Twenty seven percent had no preference. In our own sedation practice we have found lidocaine iontopheresis very helpful because the onset (5-6 minutes) is so much faster than EMLA. A few patients in this study and in our experience do not tolerate the stimulation of iontophersis, but the majority do extremely well. Your experience and opinions on the use of these medications are welcome. Case reports will return in our next newsletter.