History of Grant`s Terms of Surrender

advertisement

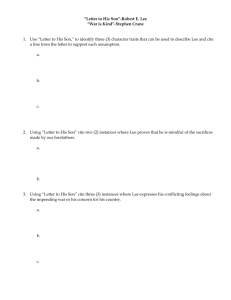

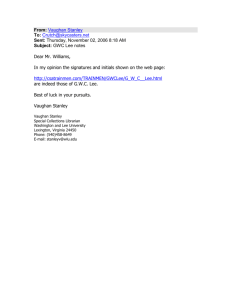

History of Grant’s Terms of Surrender Lt. Gen. U. S. Grant’s terms of surrender given to Gen. Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, were a defining point in the Civil War. Negotiations leading up to the surrender began April 7, with Grant’s communication to Gen. Lee requesting the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia in order to avoid further bloodshed, to which Lee replied by asking what terms would be offered. Grant responded the following day that his one condition would be that the men and officers of the Army of Northern Virginia would not “take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged.”[1] He further requested to meet with Lee, or his representatives, to arrange definite terms of surrender. Lee agreed to meet—not necessarily to surrender his army—but to discuss the terms which might lead toward “restoration of peace.” While Lee requested a meeting on the morning of April 9, Grant replied that he had “no authority to treat for peace” and graciously declined. Another dispatch from Lee requested a meeting to discuss the terms for surrender of his army. A short truce was declared by Gen. Meade after reading Lee’s note to Grant. A meeting was finally arranged. Lee, accompanied by Col. Charles Marshall, his military secretary, and Col. Babcock of Grant’s army, was conducted by a resident of Appomattox Court House, Wilmer McLean, to McLean’s own residence, where he awaited Gen. Grant. Grant entered while some of his staff—Generals Sheridan and Ord—remained outside until Grant had a brief conversation with Lee. The two generals discussed the terms by which Grant would receive the surrender of Lee’s army: “officers and men surrendered to be paroled and disqualified from taking up arms again until properly exchanged, and all, arms, ammunition, and supplies to be delivered up as captured property.” Lee agreed and asked Grant to write the terms so that they could be acted upon. Grant called for his order book and began to write down his terms. “The leaves had been so prepared that three impressions of the writing were made. He wrote very rapidly, and did not pause until he had finished the sentence ending with ‘officers appointed by me to receive them.’ Then he looked toward Lee, and his eyes seemed to be resting on the handsome sword that hung at that officer’s side. He said afterward that this set him to thinking that it would be an unnecessary humiliation to required the officers to surrender their swords, and a great hardship to deprive them of their personal baggage and horses, and after a short pause he wrote the sentence: ‘This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage.’ When he had finished the latter he called Colonel (afterward General) Ely S. Parker, one of the military secretaries on the staff, to his side and looked it over with him and directed him as they went along to interline six or seven words and to strike out the word ‘their,’ which had been repeated. When this had been done, he handed the book to General Lee and asked him to read over the letter.”[2] When Lee read the two-page draft, he noted that the word “exchanged” had been omitted on the second page, and with Grant’s permission, marked in pencil where it should be inserted. Grant then directed Colonel T. S. Bowers of his staff to make a copy of the draft in ink. Bowers turned the responsibility over to Colonel Parker, whose handwriting was considered the best on the staff. Finding no source of ink in McLean’s house, Colonel Charles Marshall furnished his own inkstand for Parker’s use, prompting Colonel Horace Porter to comment that , “we had to fall back upon the resources of the enemy. . ..”[3] Meanwhile, Lee instructed Colonel Marshall to draft a letter of acceptance of the terms of surrender, and after perusing it, Lee asked him to make a final copy in ink. The paper for the document was provided by Grant’s staff. While Marshall and Parker copied the letters, General Grant introduced his staff and general officers to Lee. Colonel Horace Porter’s account of the surrender indicated that Lee showed little expression until he showed surprise when introduced to Colonel Parker. “Parker was a full-blooded Indian, and the reigning Chief of the Six Nations [of Iroquois]. . . .the natural surmise was that he [Lee] at first mistook Parker for a Negro. . .”[4] That Porter was incorrect in this statement is proved by Colonel Ely Parker’s own account, in which Lee said to him, “I am glad to see one real American here” to which Parker replied after shaking Lee’s hand, “We are all Americans.”[5] After Parker completed his copy of the terms, he “brought it to General Grant, who signed it, sealed it and then handed it to General Lee.”[6] After further discussion, Lee and Marshall left McLean’s house and returned to their headquarters with the documents. Thirty-two years later, in a letter to Major George W. Davis dated 18 May 1897, Charles Marshall wrote that he had “seen among my papers, the original or a copy of the letter from General Grant. . .I am sure, if I ever had the paper, as I think I had, I did not give it to Col. Burton N. Harrison.. . . [General Grant] directed Col. Parker to make a copy in ink of his letter to Gen. Lee.. . . There was no ink in the room, but I had a small box wood ink-stand in my pocket and I think also a steel pen in a small satchel which I generally carried. I gave Col. Parker the inkstand (and I think the pen) with which he proceeded to copy Gen. Grant’s letter in ink from the tissue paper copy. . . . Col. Parker then took the ink copy of Gen. Grant’s letter to Gen. Grant, who had remained sitting in the same place as when he wrote the pencil copy. . . the latter signed the ink copy of his letter to Gen. Lee. . . Col. Parker then handed to me the letter of Gen. Grant which the latter had signed. . . I will make a careful search for the original of Gen. Grant’s letter, and if I find it, will with the consent of Gen. Custis Lee, furnish it to you for the use of your office.”[7] The Rest of the Story…. On October 12, 1955, the 85th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s death, Charles A. Marshall, son of Col. Charles Marshall, presented two documents to Stratford at a ceremony on the Great House lawn: Grant’s Terms of Surrender and Lee’s Farewell to his Troops [General Order No. 9]. Marshall, a Baltimore lawyer and the youngest son of Col. Marshall, had been custodian of his father’s war papers. According to an account of a conversation after the ceremony, Marshall said that his father had asked Lee, “ ‘To whom shall I turn over these documents?’ To which Lee had replied, ‘There is no Confederate government anymore, so just keep them.’ The papers had been in the possession of the Marshall family since the surrender.”[8] Sir Frederick Barton Maurice used the document as a resource in his book on Marshall’s years with Lee, An Aide-de-Camp of Lee. . ., published in 1927. Maurice was instrumental in convincing Marshall’s son and namesake to place his important documents “in some appropriate place, other than his home, where they might be preserved for posterity. Mr. Marshall stated that he felt ‘Stratford’ was the proper place.”[9] Charles Marshall was already familiar with Stratford since his sister-in-law Isabel Couper Marshall, wife of H. Snowden Marshall (Charles Marshall’s older brother) of Georgia, had been an active member of Stratford’s Board of Directors from 1931 until her death in 1936. Grant’s “terms of surrender” document has at various times been on temporary display since its arrival at Stratford. It was loaned to the Virginia Historical Society for its Lee and Grant exhibition that opened in October 2007 in conjunction with the bicentennial of Lee’s birth. From there the exhibit traveled to the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis, then New York Historical Society, and closed at the Museum of Southern History in Houston in September 2009. While on exhibit, the document was alternated with an excellent facsimile to reduce the amount of its exposure to light. This important document—one that positively impacted America’s ability to heal her war wounds— currently awaits much-needed conservation treatment to help preserve it for posterity. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------[1] U. S. Grant to R. E. Lee, 8 April 1865 [2] “The Surrender at Appomattox Court House” by Horace Porter, Brevet Brigadier General, U.S.A. http://www.civilwarhome.com/surrender.htm [3] Horace Porter, p.10 [4] Horace Porter, p. 10 [5] Lt. Col. Ely S. Parker, http://www.nps.gov/apco/parker,htm [6] Lt. Col. Ely S. Parker [7] Col. Charles A. Marshall to Maj. George W. Davis dated Baltimore, MD 18 May 1897 [transcript of letter in duPont Library files] [8] The Westmoreland News, October 21, 1955, “Lee Surrender Papers Now At Historic Stratford” [9] Westmoreland News, Oct. 21, 1955