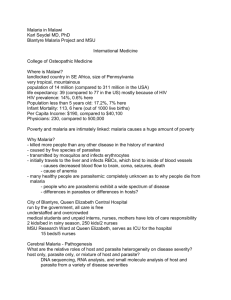

Malaria

advertisement

Guidelines for the management of Malaria Epidemiology Malaria continues to be one of the most important and devastating infectious diseases in the developing areas of the world. It is a threat for UK travellers travelling to malarial areas and immigrants arriving from malarial areas. Every year, around 2000 cases of malaria are brought into the UK from travellers returning from countries where there is a risk of contracting malaria. Last year over 5 million trips from the UK were made to countries that put travellers at risk of contracting malaria. Diagnosis Because malaria cases are relatively rarely seen in the UK, misdiagnosis by clinicians and laboratories has been a commonly documented problem. However, malaria is a common illness in areas where it is transmitted and therefore the diagnosis of malaria should routinely be considered for anyone who has travelled to an area with known malaria transmission in the past several months preceding symptom onset. Symptoms of malaria are generally nonspecific and most commonly consist of fever, malaise, weakness, gastrointestinal complaints (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea), neurological complaints (dizziness, confusion, disorientation and coma), headache, back pain, myalgia, chills and or cough. The diagnosis of malaria should also be considered in any person with fever of unknown origin regardless of travel history. Patients suspected of having malaria infection should be urgently evaluated. Treatment for malaria should not be initiated until the diagnosis has been confirmed by laboratory investigations. Presumptive treatment without the benefit of laboratory confirmation should be reserved for extreme circumstances (strong clinical suspicion, severe disease, impossibility of obtaining prompt laboratory confirmation. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria can be made through microscopic examination of thick and thin blood smears. A negative blood smear makes the diagnosis of malaria unlikely. However, because non-immune individuals may be symptomatic at very low parasite densities, that initially may be undetectable by blood smear, blood smears should be repeated every 12-24 hours for a total of 48 to 72 hours. After the presence of malaria parasites on a blood smear are detected, the parasite density should then be estimated, this is done by our laboratory. Treatment Once the diagnosis of malaria has been confirmed, appropriate anti-malarial treatment must be initiated immediately. Treatment should be guided by 3 main factors; the infecting plasmodium species, the clinical status of the patient, and the drug susceptibility of the infecting parasites as determined by the geographic area where the infection was required. Determination of the infecting plasmodium species for treatment purposes is important for 3 main reasons; plasmodium falciparum infections can cause rapidly progressive severe illness or death while the non-falciparum (P. vivax, P. Ovale, or P. malariae) species rarely cause severe manifestations. For plasmodium falciparum infections the urgent initiation of appropriate therapy is especially critical. The second factor effecting treatment is the clinical status of the patient. Patients diagnosed with malaria are generally categorised as having either uncomplicated or severe malaria. Patients diagnosed with uncomplicated malaria can be effectively treated with oral anti-malarials. However, patients who have one or more of the following clinical criteria; impaired consciousness – coma, severe normocytic anaemia renal failure pulmonary oedema acute respiratory distress syndrome circulatory shock disseminated intravascular coagulation spontaneous bleeding acidosis haemoglobinuria jaundice repeated generalised convulsions parasitemia of > 5% are considered to be manifestations of more severe disease and should be treated aggressively with parenteral antimalarial therapy. If the diagnosis of malaria is suspected and cannot be confirmed or if the diagnosis of malaria is confirmed but the species determination is not possible, antimalarial treatment effective against plasmodium falciparum must be initiated immediately. After initiation of treatment the patients clinical and parasitological status should be monitored. In infections with P. falciparum, blood smears should be made to confirm adequate parasitological response to treatment i.e. decrease in parasite density followed by clearance. Treatment in most parts of the world, falciparum malaria is resistant to Chloroquine, which is now not given as a treatment. Oral Treatment Quinine 10mg/kg (of Quinine salt) 3 times a day for 7 days. then if Quinine resistance known or suspected either Fansidar single dose – up to 4 years half a tablet, 5-6 years 1 tablet, 7-9 years 1.5 tablets and 10-14 year olds 2 tablets or Clindamycin (unlicensed indication) 20-40mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses for 5 years and upwards. Alternatively Malarone or Riamet may be given instead of Quinine. necessary to give Fansidar after Malarone or Riamet. It is not Dosage of Malarone; less than 11kg no suitable dose, 11-20kg 1 standard tablet daily for 3 days, 21-30kg 2 standard tablets daily for 3 days, 31-40 3 standard tablets daily for 3 days and over 50kg 4 standard tablets daily for 3 days. Dosage of Riamet; over 12 years and over 35kg 4 tablets initially followed by 5 further doses of 4 tablets each given at 8,24,36, 48 and 60 hours. Not suitable if under 12 years or under 35kg. IV treatment. IV Quinine; loading dose 20mg/kg (maximum 1.4g) over 4 hours. Then after 8 hours maintenance dose of 10mg/kg (700mg maximum) of Quinine salt infused over 4 hours every 8 hours until the patient is well enough to take tablets to complete a 7 day course. This should be followed by Fansidar. Benign malaria Plasmodium vivax less common than ovale or malariae. Treatment is with Chloroquine. Chloroquine 10mg/kg of base (maximum 600mg) then a single dose of 5mg/kg (maximum 300mg) after 6-8 hours, then 5mg/kg (maximum 300mg) daily for two days. Then for a radical cure for vivax/ ovale; Primaquine 250mcg/kg daily for 14 days (maximum 30mg). If in doubt about treatment ring the London School of Tropical Medicine, their switchboard number is 0207 387 9300. If there is severe malaria but the blood smear is reported as plasmodium vivax, ovale or malariae, the patient should be treated for plasmodium falciparium in case of a mixed infection or misdiagnosis. Treatment should continue with a parasite count every day until the parasite density is less than 1%. Parenteral quinine is cardiotoxic and should be administered in an HDU setting with continuous cardiac and frequent blood pressure monitoring. It may cause ventricular arrhythmias, decrease in blood pressure, hypoglycaemia and prolongation of QTc interval. Infusions should be slowed or stopped if there is an increase in the QRS complex by more than 50% or if the QTc is greater than 0.6 seconds, or if there is hypotension, which is unresponsive to a fluid challenge. There should be close monitoring of BMs. Exchange transfusion can be considered for particularly severe malaria, and the American CDC recommends that exchanged transfusion be strongly considered for persons with a parasite density of more than 10% or if complications such as cerebral malaria, nonvolume overload pulmonary oedema, or renal complications exist. Always discuss this with your consultant, and it may be best to discuss it with the London School of Tropical Medicine. Ref : CDC treatment guidelines for malaria, 2004 ALS 07/2005 reviewed 2008, next review 2011