Aquatic Animal Health Subprogram:

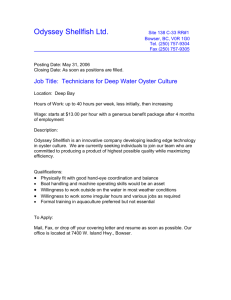

advertisement