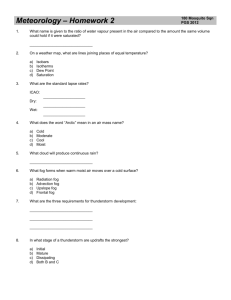

Lost_In_The_Fog - Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

advertisement

SUMMARY OF THE DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF LOST IN THE FOG DURING HIS STAY AT THE UC DAVIS SCHOOL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE, AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE TREATMENT Prepared by Dr. W. David Wilson Director of Large Animal Clinical Services Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, University of California-Davis Background: Lost in the Fog, a 4-year-old Thoroughbred racehorse, presented to the Equine Emergency and Critical Care Service at the UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH) at approximately 6:30 PM on the evening of Sunday, August 13th. The horse was reported to have been in full training until 4 days previously and had raced as recently as mid-July. He was reported to have started to show intermittent low-grade fever and lethargy, starting on 8/09/06. Two days later he became more lethargic, had a reduced appetite, and showed signs consistent with mild abdominal discomfort (stretching, looking at his flanks, laying down more often than normal). Blood samples collected for further diagnostic testing by Dr. Donald Smith, Lost In The Fog’s regular veterinarian, revealed a mild anemia; otherwise, results of other tests performed on these samples were unremarkable. The horse initially responded positively to symptomatic treatment administered by Dr. Smith, and the excellent care provided by Lost In The Fog’s trainer, Mr. Greg Gilchrist, and his experienced staff. Signs of abdominal discomfort (colic) recurred during the afternoon of 8/13/06. When Dr. Smith examined Lost In The Fog at that time, he found that his gastrointestinal sounds were absent and that his spleen was larger than normal. Recognizing the need for the more advanced diagnostic capabilities provided by specialists at the VMTH, Dr. Smith arranged for emergency referral by contacting Dr. Gary Magdesian, a board-certified specialist in Equine Internal Medicine and Critical Care, and Chief of the VMTH’s Equine Medical Emergency and Critical Care Service. Dr. Smith administered an analgesic prior to loading Lost In The Fog on the trailer in order to assure his comfort during the 90-minute journey from Golden Gate Fields to the VMTH. Examination and diagnostic work-up at the VMTH Lost In The Fog arrived at the VMTH in excellent condition and appeared comfortable, although he had an elevated heart rate and was mildly dehydrated. He was examined immediately by Dr. Jonathan Anderson, a senior resident veterinarian in the Equine Surgical Emergency and Critical Care Service, by Dr. Magdesian, and by Dr. Julie Dechant, a board-certified equine surgeon who specializes in abdominal surgery and the management of colic. At that time, Lost In The Fog was evaluated and triaged in a manner similar to that used for all horses that present to the VMTH with a history of, or active signs of, “colic” in order to quickly determine the cause of the discomfort and determine the optimal approach to treatment. Blood samples were collected immediately for analysis in the ICU Lab, a complete physical examination and examination of the abdomen per rectum were performed, a nasogastric tube was introduced into the horse’s stomach to relieve potential pressure created by build up of gas or fluid, and a catheter was placed in one jugular vein for intravenous administration of fluids and electrolytes to correct dehydration and support circulatory function. In addition, a detailed abdominal ultrasound examination was performed and a sample of peritoneal fluid, collected from Lost In The Fog’s abdominal cavity by introducing a catheter through his body wall at the lowest part of the abdomen, was analyzed. Abdominal X-rays were also taken to help rule out accumulated sand, foreign bodies, or enteroliths (hard intestinal stones formed by deposition of minerals around a central core) as the cause of the horse’s discomfort. Examination of the abdomen per rectum and abdominal ultrasound examination generated the most significant findings. Examination per rectum detected a markedly enlarged spleen and the edge of an abnormal mass deep within the abdomen. The presence of a greatly enlarged spleen was confirmed during the ultrasound examination, and, in addition, a large (25 by 35 centimeter), welldemarcated mass was identified in the lower portion of the spleen. A Doppler ultrasound study of this mass was then performed to determine whether it contained large blood vessels that could complicate collection of a biopsy. Large vessels with active blood flow were not found. The second suspected mass that had been detected during rectal examination could not be visualized during the transabdominal ultrasound examination because it was presumably hidden behind loops of intestine containing gas (gas reflects the ultrasound beam and does not allow it to penetrate to visualize deeper structures). An additional finding on the ultrasound examination was a mildly increased amount of peritoneal fluid within the abdomen. Within two hours of Lost In The Fog’s arrival at the VMTH on that Sunday evening, Drs. Magdesian, Anderson, and Dechant had completed a detailed physical examination and extensive diagnostic work-up and already had the results of many diagnostic tests at their disposal. Based on their findings, the doctors were able to rule out those conditions that are most commonly encountered in horses referred to the VMTH for evaluation of colic. These include impaction of the intestine with dry feed material, accumulation of sand or gas in the intestine, enteroliths, colitis (inflammation of the colon), internal abscess, and displacement or torsion (twist) of the colon or other portions of the intestinal tract. More significantly, the team of veterinary specialists was able to render the seemingly unlikely tentative diagnosis of neoplasia (cancer), probably lymphoma, involving the spleen and potentially other areas of the abdomen, although a biopsy would be necessary to confirm this diagnosis and rule out other potential causes of the masses. They quickly devised a plan for continued emergency care and monitoring and admitted Lost In The Fog to the Equine Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where his condition could be monitored 24-hours-a-day by the experienced ICU nursing staff working under their direction. In addition, Dr. Magdesian formulated a plan for further diagnostic evaluation to confirm the diagnosis of the splenic mass as quickly as possible, determine whether other structures in the abdomen and elsewhere were involved, define treatment options, and project the short-term and long-term prognosis associated with each treatment option. Many members of UCD’s team of experts would be involved in this well coordinated effort. Lost in The Fog’s condition stabilized quickly and he spent a comfortable Sunday night in the Equine ICU. On Monday morning, Dr. Magdesian planned to repeat the abdominal ultrasound examination, in part to further investigate the potential presence of other masses in the abdomen, and in part to perform an ultrasoundguided biopsy of the mass in the spleen. At the VMTH, it is routine practice to make sure a horse’s blood clotting profile is normal before performing biopsies on organs such as the spleen, liver, or kidney that have an abundant blood supply. In Lost In The Fog’s case, one of the clotting times (PTT) was abnormally prolonged; therefore, a transfusion with 3 units of plasma was administered in order to minimize the risk of serious hemorrhage during the biopsy procedure. In addition, a blood cross-match was performed and a matched donor horse was made available in case Lost In The Fog needed fresh blood. A radiographic (Xray) examination of Lost In The Fog’s thorax was completed at this time to look for evidence of spread of the tumor to his chest. No evidence of spread to the chest was found. As soon as the plasma transfusion had been completed and Lost In The Fog’s clotting times had been rechecked to make sure the PTT had returned to the normal range, Dr. Mary Beth Whitcomb, a specialist in equine ultrasound and chief of the VMTH Equine Ultrasound Service repeated the ultrasound examination and performed the delicate ultrasound-guided biopsy with an 8-inch long biopsy needle introduced through a tiny incision in Lost In The Fog’s body wall on his left side. Dr. Whitcomb’s examination confirmed Dr. Magdesian’s findings of a cauliflower-like mass in the spleen, approximately 25cm cranial to caudal (front to back) by 35cm dorsal to ventral (top to bottom) by 20cm deep (outside to inside). Lost In The Fog tolerated the splenic biopsy procedure well and did not suffer any hemorrhage or other complications. He was returned to his stall in the ICU unit where he was maintained on intravenous fluids and had his condition monitored intensively. While awaiting the results of the splenic biopsy, Dr. Magdesian assembled a team of specialists in equine abdominal surgery, equine anesthesia, and equine oncology to develop a plan to further explore Lost In The Fog’s abdomen in order to determine whether the mass had spread beyond the spleen. In addition, this same group developed a tentative plan for surgical removal of the spleen, and potentially other tumors, if that was judged to be feasible. When preliminary histopathology results confirming that the splenic mass was indeed a lymphosarcoma were reported on 8/16/06, plans were made to hold Lost In The Fog off feed overnight on 8/17/06 to facilitate a standing exploratory laparoscopic examination of his abdomen on Friday, August 18th. Two equine anesthesia specialists, Dr. Robert Brosnan and Dr. Eugene Steffey, chief of the VMTH Anesthesia Service, planned and implemented a protocol for sedation and analgesia, while Dr. Larry Galuppo, chief of the Equine Surgery Service, his equine abdominal surgery specialist colleague, and Dr. Dechant, performed the laparoscopic examination, assisted by Dr. Anderson. Dr. Galuppo was one of the early pioneers of this procedure in the horse, describing normal and abnormal findings in articles published in widely read veterinary journals during the early 1990’s and in presentations at conferences for equine surgery specialists. Lost In The Fog was sedated, placed in the standing stocks in the Equine Surgery suite, his flanks were clipped and prepared for aseptic surgery, and local anesthetic was infiltrated into the areas on each of his flanks where the small surgical incisions would later be made. Additional amounts of sedative and analgesic drugs were administered intravenously via an IV catheter to assure Lost In The Fog’s comfort during the procedure. After creating the portal for introduction of the laparoscopic instruments, Lost In The Fog’s abdomen was distended with carbon dioxide, a sterilized telescopic video camera (laparoscope) was introduced, and the interior of the abdomen was systematically examined while viewing the image on a large video monitor. The laparoscopic examination revealed two masses that had not been visible during the earlier ultrasound examination. One mass was 25 to 30 cm in front of the left kidney, while the second was located at the base of the cecum high on the right side and measured 25 x 30 centimeters. Multiple biopsy samples were collected from the latter mass under direct laparoscopic visualization and submitted for histopathologic examination, as for the biopsy sample previously collected from the spleen. Lost In The Fog handled the laparoscopic procedure well, recovered uneventfully, and was released from the hospital into the care of Mr. Gilchrist and Dr. Smith, the referring veterinarian, on Sunday, August 20 th, while awaiting the final results of the specialized tests being performed on the biopsy samples. Dr. Alain Theon, chief of the Medical and Radiation Oncology Services at the VMTH and one of the few equine oncology specialists in the world, remained in close consultation with Dr. Magdesian during Lost In The Fog’s hospitalization at the VMTH. Dr. Theon was hopeful that if the tumor had not spread beyond the spleen, Lost In The Fog could have been cured by surgical removal of his spleen (splenectomy), perhaps together with a short course of chemotherapy, the exact nature of which would be determined by the pending results of tests on the biopsies. Considering the size and location of the additional masses found during the laparoscopic examination, Drs. Theon, Magdesian, Galuppo, and Dechant deemed that a surgical cure was not to be feasible at this time, although they did not rule out the possibility of adjunctive surgical treatment if the size of the masses could be reduced. Nor did they rule out the possibility of chemotherapy. To this end, they recommended that Lost In The Fog be started on a course of treatment with Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid immunosuppressive antiinflammatory medication, with the goal of reducing the size of the masses. Lymphoma in the horse generates a considerable inflammatory response characterized by influx into the tumor of cells, many of which are reactive lymphocytes. These inflammatory cells may contribute substantially to the size of the tumor masses. By suppressing this inflammatory reaction, corticosteroids often shrink lymphomas considerably, making them more amenable to surgical removal or chemotherapy, as well as reducing their impact on the function of the horse’s organs, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Pressure on the GI tract by the lymphoma masses in the abdomen was likely the cause of the colic signs experienced by Lost In The Fog initially. The splenic biopsy samples, which were pale yellow in color and of firm consistency, were submitted to the VMTH’s Pathology Service for evaluation. In addition to standard cytologic, histopathologic (microscopic) examination, the samples were evaluated using two state-of-the-art procedures, immunohistopathologic examination on fresh frozen samples and clonality testing, that were developed at UC Davis by pathologist, Dr. Peter Moore, and his research group. Standard histopathologic examination involves fixing biopsy samples in formalin, embedding them in paraffin blocks, slicing them into ultrathin slices, staining them with stains that are taken up by different cell types and cellular organs to different degrees, and then examining them under a high magnification microscope. This type of testing allows pathologists to determine whether the architecture of the organ in question is normal or abnormal and gives them an overall impression of the types of cells that may be invading the organ. In Lost In The Fog’s case, the architecture of the spleen was clearly abnormal and areas were invaded by islands of similar-looking abnormal cells resembling lymphocytes. These histopathology results, which were available within 48 hours, were highly suggestive of lymphoma but, because of the unique cellular response that horses show in tissues invaded by lymphoma cells, it was not possible to confirm the diagnosis of lymphoma with 100% certainty, or to determine the specific type of cell involved, without the use of more sophisticated laboratory methods. Tumors form when mutations (mistakes) happen during the normal process of division and multiplication of cells within the body. Normally, these mutated offspring do not cause a problem because they are quickly detected and destroyed by the body’s immune surveillance system. If the body does not recognize these mutated cells, however, they tend to multiply rapidly, unhindered by the body’s normal regulation mechanisms, and a tumor is formed. In benign types of cancer, the tumor grows slowly in the organ in which it forms, whereas in more malignant types, the tumor grows rapidly and spreads via the bloodstream or via lymphatics to invade organs elsewhere in the body. In the case of lymphoma, the progenitor (parent) cells are lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are important components of the body’s immune system and circulate in the bloodstream as members of the family of white blood cells. They also populate lymph nodes and lymphoid centers in the spleen and other organs. Because lymphocytes are normal constituents of blood, lymphoma in most species, including humans and dogs, typically causes lymphoid leukemia, an increase in the number of lymphocytes in the circulation. Under these circumstances definitive diagnosis can often be achieved by examination of blood samples. This is rarely the case in the horse, however; therefore, it is necessary to examine biopsies collected from abnormal tissue masses. Complicating matters further is the fact that not all lymphocytes in the body are the same. This is important to recognize because it has an important impact on the choice of drugs and dosage protocols that could potentially be used in chemotherapy and on the likely outcome of such chemotherapy. Whereas all lymphocytes are descendents of a common lymphoid stem cell, they differentiate into two main families (B-cells and T-cells) during development. Descendents of these progenitor B-cells and T-cells then differentiate further to generate many families of lymphocyte subtypes that each play a specific role in the body’s coordinated immune response to infectious agents and other challenges. Each family and subfamily of lymphocytes expresses unique identifying markers on their surface. Many years of painstaking research performed by Drs. Peter Moore, Jeff Stott, and their colleagues in the School of Veterinary Medicine at UCD, has very recently resulted in the production of antibodies that allow pathologists at UCD to examine biopsy samples and to not only identify that a suspected tumor is of lymphocyte origin, but also to precisely define the subfamily of lymphocytes involved. In Lost In The Fog’s case, standard immunohistochemical staining methods using commercially available reagents on the formalin-fixed biopsy sample failed to provide the needed information. Fortunately, Dr. Moore was able to reach an accurate definitive diagnosis by applying the unique reagents he has developed in his laboratory to a tiny sample of Lost In The Fog’s splenic biopsy that had been stored fresh frozen. The certainty of diagnosis was further verified by results of clonality tests developed in Dr. Moore’s laboratory, the only laboratory in the world that can perform this testing. Results of the tests performed by Dr. Moore confirmed the splenic mass to be a lymphoma of B-cell origin. The following is a quote from the report prepared by Dr. Moore and his colleagues, Drs. Robert Higgins and Jenny Luff, specialists in pathology: “the sections examined were histologically consistent with a large cell lymphoma. The diagnosis of B cell lymphoma was based upon the positive immunoreactivity with CD11a (leukocyte marker), CD21 (B cell marker), and CD79a (B cell marker) on sections of frozen tissue and the results of clonality (clonal rearrangement of IGH - immunoglobulin heavy chain gene). The sample was negative for T cell markers on frozen sections (CD3, CD4, and CD8).” Dr Moore, working with fellow pathologists, Drs. Jim MacLachlan and Patricia Gaffney, applied the same testing procedures to the biopsy sample collected from mass at the base of the cecum during the laparoscopic procedure and confirmed that it was a B-cell lymphoma identical to that found in the splenic mass. Despite the need to apply many intricate and sophisticated tests, accurate characterization of Lost In The Fog’s primary cancer and metastatic masses was achieved within 10 days of his presentation to the VMTH, a timeframe that is rarely achieved in human medical centers. Drs. Magdesian and Galuppo will visit Lost In The Fog at Golden Gate Fields on August 31st and, working with Mr. Gilchrist and Dr. Smith, will perform another detailed physical examination, bloodwork, and abdominal ultrasound examination to evaluate shrinkage of the lymphoma mass in the spleen. In addition, they will examine the abdomen per rectum to determine whether the mass at the base of the cecum has changed in size. If it is determined that the masses have shrunk considerably, the possibility of surgical removal will be revisited and discussed with Mr. Gilchrist and Mr. Aleo. If the masses remain inoperable, complete cure is likely unattainable. In that case, the prospect of inducing remission of the cancer with chemotherapy will be revisited and discussed in detail. Dr. Alain Theon has in recent years performed a substantial amount of pioneering research on equine tumors and has made tremendous progress in establishing safe protocols for high dose systemic chemotherapy in horses. He has now developed a standard protocol of combination chemotherapy that includes doxorubicin and has used this protocol to treat a substantial number of horses with tumors. The aggressive drug doses included in this protocol could potentially induce remission of Lost In The Fog’s tumors, although it is unlikely that a complete cure could be accomplished. If chemotherapy is pursued, Lost In The Fog would be monitored very closely for potential side effects, many of which are the same as those seen in human chemotherapy patients. Allergic reactions, bone marrow suppression, gastrointestinal upsets, adverse impacts on fertility, and adverse effects on the heart, are all potential complications that might need to be addressed. On a positive note, Dr. Theon’s work to date indicates that horses tolerate high dose chemotherapy much better than do many species, including humans and dogs. Despite the many advances Dr. Theon and his colleagues have made in the treatment of tumors in horses in recent years, Lost in the Fog's condition highlights the tremendous need for further research and funding in this important area.