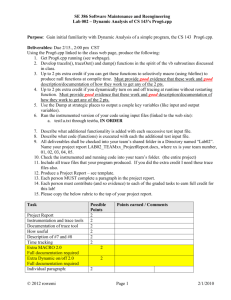

(This is still a draft version

advertisement

A Revolution Has Ended By David Ryan Quimpo The small city of Utrecht in the Netherlands is a very pleasant place to live. It is not as busy as Paris, London and the other big cities of Europe. It is not as commercialized as Amsterdam, nor as business-like as the port city of Rotterdam. And unlike small towns in Holland, Utrecht has the infrastructure of a city because it is home to the University of Utrecht, the largest university of Holland. Utrecht is first and foremost, a university city. For almost six months, I lived with a very hospitable Dutch family, in the attic of their house. The same residential place at Van Lidth de Jeudestraat served as the original headquarters of the Filippijnengroep, the Dutch solidarity group when it was founded in the late ’70s. The attic was large enough to have two bedrooms and a third room transformed into an office. I occupied one bedroom while the other bedroom was rented out to a Dutch student. The reorganization in mid-1986 included a new assignment for me which was to be head of the revolutionary movement’s network in Western Europe. It meant that I had to leave my family in Paris, base myself indefinitely in Holland and shuttle from Utrecht to Paris and back to Utrecht every month. The February EDSA revolution installed the government of Corazon “Cory” Aquino. As the wife of martyred hero Benigno Aquino. Cory had been the rallying point of the opposition against the Marcos dictatorship. Cory’s government incorporated into a shaky coalition all those who had fought Marcos – from rightists like Enrile and Ramos to progressive politicians. The Enrile-Ramos group dominated the coalition and would eventually succeed to prepare Ramos as the next president. Rebel soldiers identified with Enrile, together with Marcos loyalists, made several attempts at coup d’etat. None of these attempts succeeded, but President Cory Aquino was pushed more and more to give concessions to the right and to eventually remove left-leaning leaders from her government. Within the CPP-NDF, there was strong criticism of the boycott position taken by the Party during the 1986 snap presidential election that led to its marginalization in the EDSA Revolution. However, the feeling was that not everything was lost. The people’s gains in the revolution obliged the new Cory government to allow “democratic space” for revolutionary forces to grow. More importantly, the CPP, the NDF and the NPA still had their forces intact. 1 Among the gains of the EDSA revolution was the release of political detainees. Among those released was CPP founding chairman Jose Maria “Joma” Sison. After his release, Joma went on a speaking tour outside the Philippines. It was around 11 a.m. of that sunny morning of January 23, 1987 when Joma and his wife, Julie, arrived at the attic office at Van Lidth de Jeudestraat. It was my responsibility to receive Joma in Europe in behalf of the kasama in Europe. Over the years, through his writings, Joma had had a strong influence on me; yet, it was actually my first time to meet him. The purpose of Joma’s visit to Europe, to our knowledge, was that it was a continuation of his lecture tour as a “professor.” The tour would cover not only academic circles but also the solidarity network. His arrival in Europe was however preceded by his recent writings and published lectures. Comrades and supporters in Europe, after reading these papers, and hearing feedback from the countries he had already passed, expressed worry. “Joma’s terminology, his language of the ’60s, may turn off people in Europe,” one kasama commented. Somehow, the pressure was on me to find a solution. I hadn’t posed any questions yet when Julie, in a show of authority said “Do you know who we are?” Awkwardly I explained that we in the Western Europe committee hadn’t received any information or instruction regarding their trip, particularly pertaining to CPP-NDF matters, and that we were at a loss as to how we could help them. Joma, who was silent in the beginning intervened, saying that, in the course of their European speaking tour, they could perhaps help explain to kasamas the methods of conducting international relations. Somehow, the air became much lighter. In the days that followed, as I accompanied the couple to various occasions to meet comrades and solidarity supporters, a degree of close camaraderie developed between Joma and me. For almost two years that followed, Joma and I were together practically every week, and often, every day. On a typical day, especially after heavy meetings, I would arrange for comrades to meet in the evening at a pub at Nobelstraat, about a block away from the NDF office. After a while, there would be three of us who came regularly, about three times a week, to the pub. A comrade, nicknamed “Mushi-mushi,” joined us. Eventually, someone described our trio as “The Good, The Bad and the Ugly.” “The Good” and “the Bad” mainly preferred to down a glass or two of beer at Nobelstraat. However, “the Ugly” wanted more than beer. He wanted to dance. Dance at discos along the beautiful canal street called Oudegracht. He said he wanted to dance for the exercise. Word would spread among comrades and solidarity supporters in Europe that Joma had become the “disco kid.” In 1987, the CPP-NDF in Europe faced a big problem of expanding its organization and influence, despite that fact that there was great potential. Many European organizations wanted to support the struggle in the Philippines and emerging Filipino migrant communities in different European cities were eager for organizations pushing for migrant welfare. The problem was that the CPP-NDF was inward-looking and tended to be organized in a 2 conspiratorial way. It tended to try to recruit everybody into its secret organization rather than allow and respect the full initiative of solidarity groups and Filipino migrant organizations. The problem traced back to a decade earlier when “Mario” and his wife “Lani” were deployed to Europe. As the first CPP cadres in Europe, they were tasked to look for arms for the NPA. The couple interpreted this assignment somewhat narrowly. Consequently, they found the support activities of solidarity groups as hindrances to their main assignment. For a while, in 1980, they even transferred their base of operations from Utrecht to Rome to escape the activities of the Dutch support group, Filippijnengroep. But the solidarity network had its own dynamics and continued to expand during the Marcos years. To resolve the conflict of trying to encourage support from solidarity groups on one hand and to devote time to looking for arms, the couple sought to recruit all the European supporters that they could to the CPP-NDF secret network. By the middle of the ’80s, a big majority of the CPP-NDF secret organizations consisted largely of Europeans instead of Filipinos. Most of these Europeans had the point of view and agenda of the solidarity support groups rather than the point of view and agenda of the CPP-NDF. Joma impressed on me the “correct” methods of work, “We conduct our international relations on three levels: first, people-to-people relations, in which European support groups are mobilized to extend support to people’s organizations in the Philippines; then, state-tostate relations in which the NDF, representing the future Philippine revolutionary government, relates to European political parties who are in power or are junior partners of parties in power, as well as with national liberation movements elsewhere in the world that have representatives in Europe; and finally, [Communist] Party-to-Party relations.” Somehow, guided by this classic communist framework, we in Western Europe were able to conceptualize the direction and orientation of our international relations work. Eventually, I put these ideas down in writing. This paved the way for distinct open networks for the solidarity and migrant Filipino networks, separated from, but complementing, the clandestine CPP-NDF organization. While Joma had some useful ideas, such as his framework for conducting international relations, he had other ideas that belonged to another epoch or to a world that existed only in his imagination. “I will not close the doors to the Soviet Union,” Joma said. He insisted that the CPP could overcome its isolation in the communist world dominated by the Soviet Union and even approach the Soviet Union. For him it was only a question of “method.” And his method was a simplistic idea of dropping the CPP label of the Soviet Union as “social imperialist” and by approaching the Soviet Communist Party with the formula of “We-wish-to-establish-friendlyrelations-with-your-party-but-reserve-fraternal-relations-only-with-genuine-[Maoist]parties.”1 Once, when we travelled to Paris together, Joma wrote a letter to Mikhael Gorbachev, then 1 In Maoist terms, “fraternal relations” meant unity in ideological outlook, while “friendly relations” meant political but not ideological unity. 3 secretary-general of the CPSU and President of the Soviet Union. He imagined that with a few statements of the CPP seeking “friendly relations” and treating past disagreements as “water under the bridge,” he could get Gorbachev to invite him to the 70th anniversary celebration of the Bolshevik revolution. He asked the rest of us in the delegation, “Shall I sign the letter with a star in my signature or not?” We debated for a while if the letter should be coursed through the Communist Party of France (PCF) or through the Soviet embassy in Paris. We arranged for the latter. There was no reply whatsoever to the letter. Gorbachev simply snubbed Joma. Suddenly the CPSU became “revisionist” and the Soviet Union became “social-imperialist” all over again. Joma would later blame others like Rafael Baylosis of pressuring him in 1987 to abandon his Maoist critique of the Soviet Union. However, if there was any real pressure, it came from Mario who at that time felt frustrated, after years of knocking on different doors in Africa and Middle East and Latin America, in the quest for arms. In the spring of 1988, I was reassigned back to France. The work was mainly organizing Filipino migrants. However I continued to attend meetings in Holland from time to time. And during such occasions, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly” would go out to pubs. In one of these occasions, he asked me how much I knew about a certain comrade named “Resty.” “Were you the one who recruited him? Did you not clear him first with the Southern Tagalog party organs before reintegrating him? Are you certain he is not an enemy agent – a deep penetration agent?” I answered his questions, saying that I could vouch for “Resty” to be a good comrade, that I was certain of his background and that he was not an enemy spy. Joma was apparently not satisfied because later, he again posed the same questions to me. Later I learned that his investigative questions were part of a campaign called “Olympia.” It was one of a number of campaigns2 undertaken by the CPP to rid itself of “DPAs” – deep penetration agents. The major ones were “Cadena de Amor,” “Ahos,” “Operation Missing Link.” and “Olympia.” What started out as an effort to investigate a limited number of people became a full-blown nightmare for everyone in the movement. Torture was used in the investigation of suspects, who innocent or otherwise, pointed to other comrades to relieve the extreme pain. A chain reaction followed and with it, panic enveloped entire organizations. The “collective paranoia”3 resulted in other abuses and eventually massive killings. I considered myself very lucky to have been out of the country in the middle and late 90s. Middle-level cadres of the CPP had found themselves in an unavoidable situation: Either you were the suspect or you were the “judge.” Or sometimes even both! 2 Dozens of kasama were killed in “Cadena de Amor,” the first major anti-DPA campaign, which was carried out in the Quezon-Bicol zone in 1982. “Ahos,” the bloodiest, took place in Mindanao from July 1985 up to March 1986. Hundreds of comrades and supporters were killed. “Operation Missing Link (OPML)” took place in Southern Luzon from February to December 1988. Sixty-six were killed and 46 tortured. “Olympia” was nationwide. It began after March 1988 and ended in November 1990. The number of victims is unknown. 3 Term used by Walden Bello, comparing the resulting phenomenon to the French revolution's Reign of Terror, “The Crisis of the Philippine Progressive Movement: A Preliminary Investigation,” Debate, No. 4, September 1992, pp. 50-51 4 Resty would later recount to me that upon learning that there were suspicions about him, he immediately confronted the Party leadership and was cleared, but only to be questioned again a few years after. What saved him from arrest was the intervention of some Party leaders who knew better the circumstances that triggered those suspicions. From 1988 to 1992, long standing debates in the CPP intensified to a breaking point. The debate focused on the CPP’s strategy of people’s war and the Party’s international position. In 1974, Joma, alias Amado Guerrero, tried to adapt Mao’s theory of “protracted people’s war”4 to Philippine conditions. In an article entitled “Specific Characteristics of People’s War” (SCPW), he declared that the country’s archipelagic character, instead of being an inherent hindrance to people’s war, could be turned into a source of strength. By building guerrilla bases and zones in major islands, the CPP’s New People’s Army (NPA) would accumulate military strength and move from strategic defensive to strategic stalemate and finally strategic offensive. Forces in Mindanao and major Visayan islands would have the long-term task “to draw enemy forces from Luzon and destroy them.” He predicted: “On the eve of the nationwide seizure of power, Manila-Rizal shall be caught in a pincer between regular mobile forces from [central base areas in] the north and from the two regions of Southern Luzon.”5 Through the years however, in the light of the rich experiences of struggle in the different parts of the country, new ideas developed that modified, if not disputed entirely Joma’s SCPW vision. On June 27, 1991, I attended a study forum in Holland discussing strategy. There were about twenty participants including Joma, my brother Nathan and other important Party leaders. I saw the forum as a vital opportunity that could perhaps establish dialogue between different groups and between Joma and Nathan. I recall one kasama in the forum saying “Come to think of it, revolutions in other countries, while inspired by other revolutions, did not really have models. Russia of 1917, China of 1949, Vietnam of 1975, Nicaragua of 1979. These revolutions have armed and secret components but did not copy strategy from others nor adopt a foreign theory of “people’s war.” Nathan expounded on his proposal for the adoption of a “political-military framework,” in which political struggle, such as the mass movement, would be regarded as just as fundamental and decisive as the armed or military struggle. He believed that since the 1986 EDSA Revolution, much had already changed. He argued that there was no longer a revolutionary situation and that neither a Maoist “protracted people’s war” nor an “insurrectionary strategy” was tenable. 4 Mao Zedong's 'theory of protracted people's war (PPW)' calls for the mobilization of the peasantry in agrarian revolution and building the red army among their ranks. Guerrilla bases and zones are established with the perspective of 'surrounding the cities from the countryside'. Sison made PPW a basic tenet of the CPP program and strategy when he reestablished the CPP in 1968. He based it on his analysis of Philippine society as "semi-colonial and semi-feudal.” 5 That I embraced such a strategy may now seem naive on my part. With the benefit of hindsight though, I think it was because I associated the Mao theory too much with two things: armed resistance and clandestine organization. These enabled the CPP be the only national force to survive and continue the struggle during the early years of the dictatorship. 5 As the theoretical discussion on strategy deepened, I posed a question to Joma in front of everyone. “Joe, it has been more than twenty years since you wrote [the book] PSR (Philippine Society and Revolution). Don’t you think it is time to write an updated one?” I don’t recall what Joma said exactly, but he lost his temper. He raised the tone of his voice saying that there are fundamental things that remain unchanged. I was shaken by the intensity of his reaction and I realized that he had hardened his position. By January 1992, I received a copy of the draft document entitled “Reaffirm our Basic Principles and Rectify the Errors” (more popularly known as “Reaffirm” document). Writing under the name of Armando Liwanag, Joma called for going back to basic principles of Maoism as spelled out in the writings of Amado Guerrero – the universality of Mao Zedong Thought, Mao’s positive view of Stalin, protracted people’s war. He called too for reaffirming Mao’s thesis on “the restoration of capitalism” in the Soviet Union and on the Soviet Party’s “modern revisionism.” He said further that the Party would need again to rectify errors, as it did in 1968 because it had deviated from the “correct line.” Branding the errors as “urban insurrectionism” and “military adventurism,” he further contended that such deviations were the cause of the bloody Ahos purge. He didn’t mention names in the document but in other CPP documents that followed, he concentrated his attack on Party leaders coming from Mindanao. I was unable to reach Joma at that time. Yet even if I had been able to, my opinion at that point no longer carried any weight in CPP-NDF structures in Europe. Nonetheless, I took up the draft document with Mushi-Mushi and I asked him to relay a message. “Tell Joma that if he pursues this ‘Reaffirm’ document, it’ll result in a mudslinging situation that’ll certainly split the party.” On June 8, after a lot of reflection, I tendered my resignation from the revolutionary movement. In my resignation letter, I wrote. “I think the time of ‘waving [Mao’s] little red book’ is over.” My resignation was the first protest inside the CPP in the form of “voting with the feet.” It happened largely unnoticed partly because comrades, including Nathan and others in Europe, still entertained hopes that the CPP could reform itself. They were then thinking that a widespread clamor among Party organizations would force the Central Committee to allow general discussions, and eventually a second Party congress. We were in an Utrecht bus when Nathan told me “I think the problem really is Joma. The Party and the revolution will go nowhere until he is removed as an obstacle.” I was surprised that he didn’t see an impending and inevitable split. “No,” I said. “Joma will win this one.” And he asked why. “Over the past few years, key CPP leaders have been arrested,” I replied. “Rodolfo Salas, Rafael Baylosis, Rolly Kintanar, Benjamin de Vera. There have been no Party congresses and 6 elections other than the founding congress in 1968. Joma, in a sense, remains the only ‘legitimate’ Party leader!” A few weeks later, I wrote my sister Susan a long letter. “I tell friends that I now have the ‘Yves Montand mentality.’ Montand, the French actor was a communist sympathizer but was critical of some communist leaders. His motto, borrowed from F. Scott Fitzgerald was ‘One needs to understand that there is no hope and yet to be determined to change things’.” “I think he [Joma] saw in [Nathan] a kind of rivalry, specially with the publication of Debate.6 By early this year, the conflict [between Joma and Nathan] had sharply escalated. But it was not merely theoretical ...” I said. “Do not be surprised if later you hear the CPP [actually Joma in the name of the CPP] attacking [Nathan] as worse than the Lavas [the leadership of the old PKP].” By September 1992, Nathan was set up for a hearing for “disciplinary action” on various trumped-up charges. “They ganged up on him,” recounted Jasmin, a party member who saw Nathan before the hearing. “It was blatantly unfair. I saw Nathan shaking in anger so I pressed on him to walk out.” It was basically a kangaroo court. Nathan questioned the very authority of the ad hoc committee, which had been constituted by certain Party “elders” based abroad to “try” him. Having been appointed to the CPP’s International Department by the Executive Committee of the Central Committee( EC-CC), Nathan argued that according to Party rules, only the EC-CC could constitute the disciplinary committee. Moreover, he questioned the impartiality of the committee since his main accuser and the head “judge” were husband and wife. As I expected, Nathan was expelled from the CPP. Nathan’s reaction to the decision was still to push for its nullification within the Party structure. It proved to be moot. Weeks later, he learned that Joma’s position and his “Reaffirm” paper had been consolidated by a bogus plenum – the “tenth plenum”7 – of the CPP Central Committee. In December 1992, Joma sent faxes to the Philippine Daily Inquirer naming Central Committee members Ric Reyes, Rolly Kintanar and Benjamin de Vera as “renegades and counter-revolutionaries.” By publicly branding the three as enemies, Joma effectively shortcircuited organizational rules and procedures. It meant that there would no longer be debate and discussion inside the Party, no Party Congress and no due process for those accused. The effect on the CPP of the “tenth plenum” and Sison’s faxes was a full blown split. Large chunks of the party and the NPA openly declared their opposition to, and autonomy from, what they called as Armando Liwanag’s Central Committee (AL-CC). The first was the Manila-Rizal region in July 1985 with about 5000 members. This was followed by two more regions and the National Peasant Secretariat. Then the Central Mindanao Region followed. Finally, most of the island regional organizations in Visayas, except Samar-Leyte, bolted. 6 Debate, which billed itself as the “Philippine Left Review,” was a quarterly publication started by Nathan Quimpo, Joel Rocamora and Edicio de la Torre in 1992. 7 The legitimacy of the “tenth plenum” was highly questionable because there was no quorum. A number of CC members, particularly those recently released from prison and those who dissented against Joma were simply not informed about, or not invited to, the plenum. 7 By the end of 1993, two conflicting forces emerged: the “reaffirmists,” who stuck with Joma, otherwise known as “RAs,” and the “rejectionists” or “RJs.” For me, the “10th plenum” signified more than a power grab, more than a party split. It marked the end of an era, the era of passionate activism. It was the death of a dynamic movement that had unprecedentedly mobilized millions of Filipinos to change their destiny. It meant no less than the end of a revolution. 8