Video transcript

advertisement

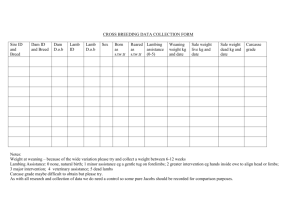

52 Menzies Wed 1130 1245 JOHN RAMSAY So Annie and I run Ramsay Agriculture. It's based in Tasmania. We have two properties. The main property is Ratho, Bothwell, and then we have another property about three hours away, in the north east of Tassie, and it runs 4,500 composite ewes, an and is a breeding operation only. Through the challenge we focused on Ratho, its main property. It's about 1,000 hectares of productive ground, and over 50% percent of this is irrigated. In irrigation, our pinnacle crop is poppies. And we do everything we can to make them the best. So poppies, you can only grow one year in three. So in the two years outside that, at the moment, we're running ewes. We've tried a bit of clover seed, but we're joining about 5,000 ewes. We plan to finish about 8,000 lambs this year, and we did that last year. And we tried cattle opportunistically. So this is a photo of our property. It's pretty flat. It's arable, it's suitable to irrigation, and that's one of our linear irrigators. So our vision is to be a highly profitable business that improves the environment, giving its stakeholders a balanced, happy, contented life and options into the future. Our goals are listed-and my goal is to have a profitable farm. I'm quite a financially focused person. However, also because of our debt levels, we need to really focus on profit and make it a number one goal. Greater than 5%, then it gives us options to look at other things. We want to decrease our exposure to debt through the land acquisition and succession. We've got quite a high debt burden. We want to maintain a balanced lifestyle. I'm not a typical farmer that works seven days a week, dawn to dusk. I want to have time with the family and make the farm a vehicle to make my goals rather than working for the farm all the time. We want to farm with best practise, we want to improve our viability, and we want to improve our environmental sustainability. So why did we do the MLA challenge? Well, the stories starts probably when I came back from RNJ College in 2001. We had the opportunity to purchase our farm that we're leasing, and the whole Clyde Valley was turning from merino sheep. We're merino sheep growers. We run about 3,000 ewes. The whole Clyde Valley was changing into poppies. We had arable land, we had water resources, so it a bit of a no-brainer. So we followed suit. We bought the farm, we started to develop it, and it worked really well. We got excellent poppy results. In between the years of poppies, we grew cereal crops, and that worked well, too. We're meeting our goals, we're making good return, and everything was going swimmingly. It coincided, though, with fresh ground, so we hadn't minded our environmental capital, and also probably a run of dry years. In 2010, the system came crashing down, and so did our profits. When the rains returned, it got back to probably what was normal years. We're farming on really fragile, probably about 10 inches of topsoil, and it's highly fragile soil. So our poppy yields suffered, and so did profit. So we looked at what we could do. We got a Caring for our Country grant for our valley, because a lot of farmers were experiencing the same problem. We got some experts in, and they said, you got to grow your poppies, but in between, grow ryegrass. Ryegrass is good for organic carbon, but also it's really good for ameliorating your soils. It actually aggregates soil particles, which will help with your drainage and help with your poppies. So we did. So we put in ryegrass, and we did a terrible job of it. We tried to run merino sheep on the ryegrass, and we made a heap of hay, and we made no money again. So we saw the MLA challenge. We thought, well, this could really help us improve the grazing side of our business. The challenge gave us various tools and resources. Some of the key tools or resources was they gave us a mentor. My mentor was John Keillor, a composite stud breeder from Victoria. Excellent guy. He knew a lot about composite sheep and set us on the right track. It also gave us a farm advisor, Sam Newsome, who gave a really good overarching picture on the farm, and particularly, the people side of the business, which we didn't expect to get out of the challenge. MLA gave a heap of tools and resources, a lot of research, a lot of online stuff that was really important to our business progression. So just some key lessons learned from the mentoring research, we probably all know it, but a key profit driver in a meat enterprise is kilogrammes of meat per hectare. All I had a paradigm that we had irrigated country, we had no shelter on the farm, we couldn't breed on our country, so we had to be finishing operations. The mentor, John Keillor really pointed out that he's seen plenty of farms like ours, and the best way to utilise your spring flush is a breeding system. So we went into a breeding system. In a breeding system, key profit drivers-- lambing percent, and key to that is the time of lambing. You feed on offer. But probably what we were missing a bit was the size of the lamb born. For a little lamb to survive exposure in our country, you need a bigger lamb. To get a bigger lamb, you can't get a big lamb out of a fine wool merino ewe, is what we had. And also, you've got to select your genetics, get your ASBVs for a bigger lamb. So this is a photo of our irrigator, a nice shutter only, some little lambs. It's not a great photo, but the only shutter really is the grass and the irrigator. So what prompted the change from merinos crossbred? I need to point out, it was a pretty tough decision to make. We had a long history of breeding. My father was a passionate wool grower, so there was a real papal issue there. Annie and I are much more pragmatic. We have a rule belief in keeping things simple. In the end, it just came down to horses for courses. We changed our farm to irrigation, and the crossbreds are much better suited. But the other key was having the mentor, having the farm advisor holding our hand to say, yeah, John and Annie, you're doing the right thing. That really helped to give us confidence. So again, a photo. This is not last spring, but probably previous two springs. We just grew all this grass, and merinos didn't do very well on it. Crossbreds did. And this year, we didn't have anything like that because the crossbreeds were able to eat the feed in front of them. I was asked at one of these talks, so what gross margins were you getting on your merinos compared to your crossbreds? And I didn't know. We actually didn't research that or budget that. It was almost a no-brainer to just make that change with the crossbreds. But I thought, well, I better go and have a look. Now a lot of benchmarking would say that a merino ewe joined a prime lamb size are most profitable, and I won't disagree with that. But if you break it down, it comes down to lambing percentage. You need about 30% more lambs in the grounding to make enterprise to cover the costs of the loss of fleece income. Our merinos were doing 66%. The crossbreds last year did 137%. So it's a much better gross margin. However, the crossbreds, just for interest, is about $500 a hectare. That's based on average land price. So current land price is probably about 20% of that. And interesting, Caroline, that you're tipping a good forecast for lamb, so our gross margin will probably be about 20% higher than that per hectares, whereas our cereal cropping is around $800 per hectare. So it shaped out quite as good as our cropping. But the key and the pinnacle to our business is the poppies. And we can range from $1,000 to $5,000. To get up to the $5,000, we need the sheep. Another tool that's we used a lot and developed our CSRI and MLA was a feed demand calculator. I won't go in to this too much. But for anyone looking at changing direction like we had, I wish we had to use this tool when we first made the change. It's great for planning, it's great for scenario analysis, and it's really simple to use. I'll just quickly go through. This is a chart here. Down at the bottom is your sheep, your stock numbers, and what they ate per month. And then your green line is your pasture grown per month, and the top line is your accumulated pasture grown per month. And it just shows where in the September, October, November, we're still not eating our feed. Come to a pinch in January, February, and winter. Typical scenario in southern Australia. So just a quick summary of the changes that we made through the challenge and the years ahead. We're cropping around about 600 hectares, continually cropping, and we've dropped that down about 200. We made about 3,000 bales of hay a year. Last year, we didn't make any. And I was really happy, because I don't think it's a great enterprise to be part of. Changed our ewe type from merinos to crossbreds. We increased our ewe numbers. When we were cropping, we only had about 1,000 ewes, and now we've got about 5,000. Lambing percentage has increased, as I've talked about. We've also increased our lamb turnoff quite considerably. When I talked to the mentor about going to a breeding system, we thought we would be breeding all these lambs, 5,000 ewes, 137%, that's 8,000 lambs. We're not going to be able to finish that many. We thought we'd be heading to a store lamb system. However, the challenge made us focus on everything we did, and we put a focus on a lamb weight gain. And my managing to focus and making sure to that we're doing the best job that we could on those lambs, we managed to turn all of them off as finished lambs but also, the second cross lamb finish is about 30% quicker than our first cross lamb, so that also helped as well. We didn't want to just focus on production. That would be costing our business as labour. We wanted to focus on our costs, so we had a labour efficiency KPI. And we managed to improve that from about 6,000 to 8,000 days per full time equivalent, and we did it really simply through changing systems. Previous to the challenge, we had three lambing dates, we had three sheep enterprises. It was a bit messy. We just simplified everything. One lambing date, one type of sheep, and that's how we made those changes. We've got more changes, more efficiencies to be had through equipment yards and line wires. But the end goal is to increase our return on assets. Last year, we did increase our return on assets. We didn't quite hit the 5%, but this year, I reckon we will be. So, are we on course to meet our vision? Poppies are fickle. We thought we had a good poppy year this year. However, for numerous reasons, they didn't come about, and that's another tough enterprise to be part of. Higher risk, higher reward. Sheep prices this year for us are great. We produced a lot of meat, and the prices are helping. So we reckon we'll be on course to make that goal of 5%. Environmental sustainability is much better with the grass system. I really like what we're doing. I think it's a much better fit and a much more robust system. I lost balance, but we'd be more balanced if we had better fences. Crossbreds are pretty tough on your fences. So what are our challenges ahead? We run a high input system. We put on urea, irrigation. It's expensive, so we've got to make sure that everything we're doing, we do it well. We got to have attention to detail, but also we've got to keep an eye on our cost, and cost-margin analysis to make sure that if we're putting the expense out there, we've got to be getting the reward at the end of the day. As with any change, this throws out some challenges. So these crossbreds are having trouble with casting. Major twin lamb disease issue last year, We've employed a livestock consultant to help us with these issues, and we're just working through those as we speak, and we think we've got some strategies to overcome those issues. And just in January this year, we had some suboptimum growth rates, and again, we're using a few strategies to improve that. Just quickly go through some pros and cons of the crossbreds versus the merino, as I see it. Pros of crossbreds, they convert long green grass well. Our merinos were getting footrot and worms, and they just weren't converting grass into meat. The crossbreds are much better and genetically suited to do that. I've mentioned that. They don't get feral. They don't get many worms. The lambs survive exposure better. They finish quicker. They carry the condition on their backside. We often found with the merinos, coming out of the spring, they were only condition score two, maybe two and a half. And come joining, you'd have to give them a heap of grain to get them back into the right conditioned score for joining. Whereas these crossbreeds, they're coming out of the spring on that sort of feed, their condition score four. No grain feeding, they carry it through, they join well, they scan well, and they carry it through the winter well, too. Also, another benefit I didn't realise that they're different grazing habits to merinos. They'll go into a paddock and clean it out and do a really good job with their rotational grazing and reducing the overburden, but also pushing it to some other country that the merinos never would. The cons. They do eat a lot. They've got a much higher density per head. They get cast on their back. Major infrastructure is needed when you make that change. They're hard on fences. They're hard on yards. They have higher production issues because they produce so many lambs. We've had the hypocalcaemia issues. Obviously, it's about horses for courses, and whatever's best for your farm. So these are my two boys. Henry and Alex and some rams we purchased last year. They're the future, and I just want to say our story's about some pretty major changes in one year through the MLA challenge. And prior to the challenge, Annie and I were not in a very happy place. We were pretty despondent. We weren't meeting our goals, are we were feeling pretty lost. But within one year, we've really turned it around. And with some good people, some good help, some good tools and resources, we feel so much more positive about our future ahead.