RENAISSANCE POETRY Modern lyric poetry begins in Tudor

advertisement

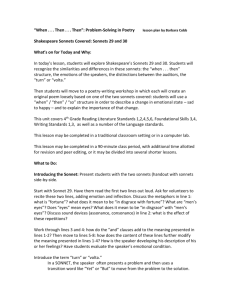

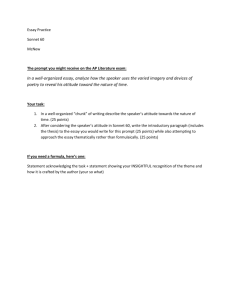

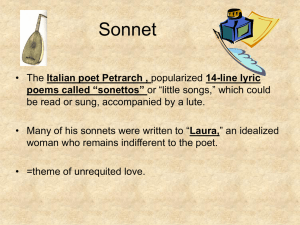

RENAISSANCE POETRY Modern lyric poetry begins in Tudor England with Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542) and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517-1547), who are both influenced by Francesco Petrarca: the former introduces the sonnet into English, the latter uses unrhymed pentameters (or blank verse). The sonnet is a 14-1ine-poem written in iambic pentameters with two different rhyme schemes, the Italian and the English one. The ltalian form is divided into two parts - the octave and the sestet - the former stating the problem, the latter suggesting the solution. The English sonnet, instead, is divided into 4 parts: introduction - expansion - further expansion - conclusion in the final couplet. Renaissance poets liked this form, since its regularity in the rhyme scheme and metrical pattern challenged the poet's skill and was a mirror of balance and order in the world. The Petrarchan conceit was the favourite device on which sonnets were built. It is a witty idea or image developed to strike the reader in the form of a metaphor, a paradox, an antithesis. John Donne and the Metaphysical poets developed a new, more colloquial style which differed from the Petrarchan one. With them, lyrical poetry became more and more experimental. The standard theme of the English Renaissance sonnets was that of 'courtly' love: poets expressed their passion for an unattainable Lady, and explored various aspects of their own emotions. This form of love was also used as a metaphor of their homage to a patroness or the Queen herself. Other recurrent minor themes were their Lady's beauty and virtues, the transience of life, and the immortalising power of poetry. The fixed form of the sonnet prompted poets to compress meaning into striking figures of speech (metaphors, paradoxes, similes, etc.). The final couplet could become an epigram, that is, a concise and cleverly formulated sentence on its own. The language was that of poetic diction, with refined, ornate, polysyllabic Latinate words, considered suitable for poetic effects. Many of these features are present in Shakespeare's sonnets, which are notable for their wide variety of style and content. But their most striking trait is their original innovation of convention. For example, the poet refuses to write conventionally of love, and always surprises the reader's expectations. Unlike traditional sonneteers, he addresses a young man - probably his patron and social superior, although attempts have been made to suggest a homosexual relationship - and a woman - a so-called 'dark lady' whose identity was never convincingly proved. The young man is beautiful while the lady isn't; the poet speaks of her physical appearance in a most uncourtly and unromantic manner. Petrarca, Pace non trovo e non ho da far guerra, Canzoniere CXXXIV Pace non trovo e non ho da far guerra e temo, e spero; e ardo e sono un ghiaccio; e volo sopra 'l cielo, e giaccio in terra; e nulla stringo, e tutto il mondo abbraccio. Tal m'ha in pregion, che non m'apre nè sera, nè per suo mi riten nè scioglie il laccio; e non m'ancide Amore, e non mi sferra, nè mi vuol vivo, nè mi trae d'impaccio. Thomas Wyatt, I find no peace I find no peace, and all my war is done. I fear and hope. I burn and freeze like ice. I fly above the wind, yet can I not arise; And nought I have, and all the world I season. That loseth nor locketh holdeth me in prison And holdeth me not--yet can I scape no wise-Nor letteth me live nor die at my device, And yet of death it giveth me occasion. Veggio senz'occhi, e non ho lingua, e grido; e bramo di perire, e chieggio aita; e ho in odio me stesso, e amo altrui. Without eyen I see, and without tongue I plain. I desire to perish, and yet I ask health. I love another, and thus I hate myself. I feed me in sorrow and laugh in all my pain; Pascomi di dolor, piangendo rido; egualmente mi spiace morte e vita: Likewise displeaseth me both life and death, And my delight is causer of this strife. in questo stato son, donna, per voi. Season: That loseth nor locketh: no wise: at my device: Plain: lament 'I Find No Peace' by Thomas Wyatt Summary The narrator expresses his despair with diametrically opposed concepts. He is unable to rest, and yet he has no fight left in him. He is optimistic yet afraid, he is ablaze yet frozen. He is soaring, yet cannot take off; he has nothing, yet he holds the whole world. Though there are no locks strong enough to imprison him, he cannot escape. The narrator feels he has no control over whether he lives or dies. He can see without his eyes, and complains without a tongue. He says he wishes to expire, and yet demands strength. By line 11 he reveals a less paradoxical contrast: that he loves another therefore must not love himself. He revels in the joy of the sadness and discomfort of this love, and although the situation is almost like a living death, the cause of his pain is his greatest pleasure. Analysis The confusion, ambiguity and vacillation of feelings and emotions connected with love is the subject of this sonnet, which is a translation of Petrarch’s sonnet 104. The poem is built from opposite sentiments and ideas to reflect the full range of feeling that love can provoke. While it seems that this relationship is an impossible affair that leads him to the brink of despair, the poet also seems intoxicated by it. The opening image of war and peace also reminds us of Wyatt’s diplomatic and ambassadorial duties, the vast changes in allegiance that he saw within his term of office and the challenges of the international political arena at this time. The metaphors used highlight the physical extremes such as burning and freezing to connote the psychological consequences of the dramatic emotions involved. Love in the tudor court was often fraught with social implications, particularly as the king himself was involved in numerous precarious romantic relationships. But, the idea of being incarcerated despite the fact that no bonds could hold him reminds us that the resultant torture is one which the narrator is willingly subjecting himself to. Alas, he derives pleasure from the situation that directly causes his pain. Line 11 is interesting as these two ideas are not usually mutually exclusive: it is possible to love another and oneself. However, Wyatt is perhaps indicating that the relationship is one dictated by the heart rather than the head; though the love feels right, the narrator cannot quiet his mind to the unsettling knowledge that his love is not a practical or logical choice. If he is prepared to put himself in danger for his love, he must not care enough about himself to prevent his own destruction. In the final rhyming couplet, the narrator makes it clear that he understand that that which gives him the most pleasure is that which causes him the most peril. http://www.gradesaver.com/collected-poems-of-sir-thomas-wyatt/study-guide/section15/ Sonnet LXXV: One Day I Wrote Her Name by E. Spenser One day I wrote her name upon the strand, But came the waves and washèd it away: Again I wrote it with a second hand, But came the tide, and made my pains his prey. Vain man, said she, that dost in vain assay A mortal thing so to immortalise! For I myself shall like to this decay, And eek my name be wipèd out likewise. Not so (quoth I), let baser things devise To die in dust, but you shall live by fame: My verse your virtues rare shall eternise, And in the heavens write your glorious name; Where, whenas death shall all the world subdue, Our love shall live, and later life renew strand: shore dost……assay: do…..try eek: also quoth I: I said; devise: plan whenas: when Questions 1. Divide the poem into three quartrains and a couplet and match them to the following summaries: a. the poet says that their love will survive even the apocalypse and will restore life again b. the poet tries twice to write his lover’s name on the sand but uselessly c. the poet replies that earthly things will die but his poetry will make his beloved eternal d. the poet’s lover says that unfortunately everything is destined to die, even her name. 2. How are direct and indirect speech used? 3. Compare the image of the name written on the shore with the name written in the heavens, What do they imply? 4. Underline the alliterations in the poem. What words do they underline? 5. Write down the rhyme scheme. Is it Petrarchan or Shakespearean? 6. What is the theme of the poem? ANALYSIS One of Edmund Spenser’s most noted sonnets is “One Day I Wrote Her Name Upon the Strand”, addressed indirectly to his fiancée, Elizabeth Boyle and part of the sonnet sequence titled Amoretti. The Spenserian sonnet displays the rhyme scheme ABAB BCBC CDCD EE, different from the Shakespearean rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. In this sonnet Spenser faces the problem of the destructive power of time, a problem which troubled Renaissance thinkers and intellectuals. In the first quatrain, the speaker declares that he wrote the name of his beloved in the sand, but the waves came along and wiped it away it. Then he wrote it again, and the same thing happened. Seeing her name thus being repeatedly wiped out, the beloved reminds him that he is trying to immortalize a mortal thing. She insists that just as the sea water washes away her name from the sands, so the sands of times will wipe away her very life. She calls her lover a “vain man” for thinking he can accomplish the impossible. Unusually for a Renaissance lady, the beloved has been given a voice here, and she seems to understand the symbolic significance of the waves leveling the sand. Not only that, she does reproach the lover for this. This provides the poet with the opportunity to make his point. The speaker believes that baser elements, that is the earthly things subject to decay and death, naturally perish in the dust, but he thinks that his beloved is too beautiful to die and then offers his verse as the means for her gaining immortality. He is hopeful that his verses will be able to eternize the memory of the beauty of the beloved and transfigure her into a heavenly being. But what he seeks to immortalize is not only the physical beauty of the beloved, but those spiritual qualities which provide the beloved with spiritual/physical beauty. So physical beauty is symbolic of the manifestation of divine beauty. The speaker then proclaims immortality for both lovers. In his sonnets, “[their] love shall live,” and not only live but by virtue of his art will their lives be renewed. He hopes further that this will help them to transcend their mundane existence and find a permanent place in the divine scheme of things. In this theme, the speaker’s confidence resembles that of the Shakespearean speaker, who continually makes his subjects immortal by capturing and framing them in his sonnets. The conclusion Spenser provides in the theme of immortality assured through poetry is not original since other poets before him, notably Horace and Ovid, had come to the same conclusion. SHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS The poem below focuses on a Petrachan conceit, an elaborate comparison, to state that the beloved is better than a summer day. Shakespeare reverses the traditional pattern according to which nature is immortal, men, instead, are mortal. SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer's lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm'd; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature's changing course untrimm'd; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest; Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this and this gives life to thee. thee: you (object) Thou art…temperate: You are ………… constant the darling buds: the beloved buds ‘summer's lease’: summer time is far too short ‘the eye of heaven’ : the sun is too hot and his gold complexion often becomes less bright and everything beautiful sometime will lose its beauty by misfortune or by nature's planned out course ‘untrimm'd’: deprived of its beauty ‘thy eternal summer’ : your youth that fair thou owest: the beauty that you possess Nor will death boast you ‘wander'st in his shade’ : belong to him ‘to time thou growest’ : you will live forever so long as there are people on this earth so long will this poem live on, ‘gives life to thee’: makes you immortal. PARAPHRASE Shall I compare you to a summer's day? You are more lovely and more constant: Rough winds shake the beloved buds of May And summer is far too short: At times the sun is too hot, Or often goes behind the clouds; And everything beautiful sometime will lose its beauty, By misfortune or by nature's planned out course. But your youth shall not fade, Nor will you lose the beauty that you possess; Nor will death claim you for his own, Because in my eternal verse you will live forever. So long as there are people on this earth, So long will this poem live on, making you immortal. QUESTIONS A. 1. Shakespeare starts the sonnet with a question. What does he ask? 2. In the second line he answers his own question with a remark. What does he say exaclty? 3. From l.3 to l.8 the poet justifies the answer. Rearrange the following in the order they appear in the sonnet: nothing beautiful last too long summer lasts too short a time even in summer the sun is sometimes covered by clouds the wind shakes the buds from the trees sometimes summer is excessively hot 4. In ll. 9-12 the poet makes a promise. What does he promise exactly? 5. Now look at the last two lines. What does the poet assert at the end? 6. The structure of the poem is based on a rigid pattern, formed by the items below. Put them in the right order and say to which lines each one corresponds: epigrammatic conclusion supporting arguments answer question turning point idealization of the beloved B. 1. The poet compares the beloved to summer, which is not the ideal season, but rather an imperfect one, inferior to the ideal “summer” of the beloved. What is the main feature of the beloved? 2. The ideal perfection of the beloved prevails. What makes him/her immortal? 3. The idea of decline is suggested by many words. Underline them in the text. Then, with a different colour, underline the adjectives and verbs in the last quartrain contrasting with the idea of approaching death. 4. What possessive adjectives and verbs does the poet attribute to death? What is the poetic device called? 5. The chiasmus in the last line of the sonnet underlines the function of this poem. What does that imply about the power of poetry and art in general? 6. Identify the turning point of the sonnet. What new argument does it introduce? 7. Write down the rhyme scheme. How is the poem organized? 8. Find example of alliteration and repetition. Are there any enjambements? 9. The sonnet can be divided into two parts: 1. lines 1-8 concerning nature and its laws; 2. lines 9-14 concerning art and its symbolic order. What image connects them? What metaphorical meaning does this image acquire in the second part? 10. The poet expresses two notions of summer, conveyed in the phrase ‘a summer’s day’ and ‘thy eternal summer’. Compare and contrast these two ideas. In what way do you think the poet considers the young man’s summer eternal? 11. Identify the theme of the sonnet. ANALYSIS Sonnet 18 uses a typical convention of Renaissance poems about the transience of youth and beauty: the comparison with aspects of nature. In this sonnet the poet begins by considering what metaphorical comparison would best reflect and at the same time preserve the image of the young man. His first idea is to compare him ‘to a summer’s day’, because the man’s youth is similar to nature in full bloom. But summer, especially in England, is often short, and the weather is changeable: one minute it’s too hot, the next the sun has disappeared and it has turned cold again. This unpredictable alternation between good and bad weather, typical of English summers, does not convey the sense of balance and harmony the poet sees in the young man’s beauty: ‘thou art more lovely and more temperate’. However it is also true that, like a real summer, the young man’s youth will not last long. In fact, it is not in nature, but only in art that the poet will be able to preserve the idea of youth, the imagined perfect day of the young man’s ‘eternal summer’ – the momentary feeling we may have sometimes that our youth will last for ever. This marks the turning point of the sonnet. In the world of the poem, the young man’s beauty will never fade or die, but will go on growing in the minds of readers for centuries to come. SONNET 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state out of favour with fortune and men weep over my position as a social outcast (emarginato) And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries And look upon myself and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featured like him, like him with friends possess'd, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate; For thy sweet love remember'd such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. PARAPHRASE When I’ve fallen out of favor with fortune and men, bootless=useless look upon=look at wishing I were like one who had more hope wishing I looked….sorrounded by friends art=skill; scope=opportunities I used to enjoy with these thoughts haply…=by chance I think of you and then my mood like the lark sullen=dark thinking of your sweet love brings such wealth …I would not change my position… All alone I weep over my position as a social outcast, And pray to heaven, but my cries go unheard, And I look at myself, cursing my fate, Wishing I were like one who had more hope, Wishing I looked like him; wishing I were surrounded by friends, Wishing I had this man's skill and that man's freedom. I am least contented with what I used to enjoy most. But, with these thoughts – almost despising myself, I, by chance, think of you and then my melancholy Like the lark at the break of day, rises From the dark earth and (I) sing hymns to heaven; For thinking of your love brings such happiness That then I would not change my position in life with kings. QUESTIONS 1. Paraphrase the sonnet in your own words 2. Is the sonnet focused on the speaker or the beloved? 3. ll.2-8 describe the characteristics of his melancholy. Say what the speaker thinks and does in this state of mind. 4. What autobiographical events may have caused his pessimism? 5. ll.5-7 reveal the person the speaker would like to be like. Describe him. 6. The sonnet can be devided into two sections. What? And where is the turning point? 7. The word ‘state’ is used three times: where and to mean what? 8. Why, do you think, the speaker uses the verb ‘trouble’ and the adjectives ‘deaf’ and ‘bootless’? What kind of religious sentiment do you think they reveal? 9. In l. 11 the lark arises from a ‘sullen earth’. Why is it said to be sullen? What is day break compared to? 10. The speaker’s ‘bootless cries’ to a ‘deaf heaven’ in line 3 have changed into ‘hymns at heaven’s gate’. What has produced this change? 11. Why does the speaker say he would not change his position with kings? 12. What are the rhyme and stress patterns? Are they regular? ANALYSIS Sonnet 29 follows the same basic structure as Shakespeare's other sonnets. The sonnet contains fourteen lines and is written in iambic pentameter, meaning that each of the fourteen lines contains ten syllables that alternate between unstressed and stressed. It is comprised of three rhyming quatrains with a rhyming couplet at the end and follows the traditional English rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Traditionally, the first eight lines of a sonnet produce a problem (a “when” statement”) that is then resolved in the last six lines (a “then” statement). Sonnet 29 includes two distinct sections with the Speaker explaining his current depressed state of mind in the first octave and then presenting a happier image in the last sestet. Synopsis The speaker describes moments of great sadness, in which he cries over his "outcast state" by himself. This "outcast state" may refer to either an unfavorable standing in society or a lack of financial success in the playwriting field. One possible explanation for this lack of success is the closing of London theatres in 1592 due to a plague epidemic. Another suggested reason for Shakespeare's "outcast state" is an instance of harsh public criticism of Shakespeare by fellow playwright Robert Greene. The speaker then says that in these times he "trouble[s] deaf heaven with his bootless cries", meaning he feels his prayers and exhortations are useless. The speaker then reveals that he is least satisfied in the things he enjoys most. The "turn" at the beginning of the third quatrain occurs when the poet by chance ("haply") happens to think upon the young man to whom the poem is addressed, which makes him assume a more optimistic view of his own life. The speaker likens such a change in mood "to the lark at break of day arising, From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate". The couplet is an emotional declaration that remembrance of his friend's love is enough for him to value his position in life more than a king's. This poem is speaker-focused and about the emotions and experiences of the speaker, not that of the beloved's. The references to heaven made throughout the poem do not reveal an institutional religious sentiment since the Speaker speaks only of heaven and not of God. First, he states that heaven is deaf to his sorrow. Then, the thought of the beloved procures a rebirth to a life where the speaker can now sing “hymns at heaven's gate”. The poem is a hymn, celebrating a truth declared superior to religion. The line three points out stressed syllables, "troub-," "deaf," and "heav'n". The heaping of stress, the harsh reversal, the rush to a vivid stress - all enforce the angry anti-religious sentiment. The repeated use of "state" is notable throughout the poem with each being a reference to something different. The first “state” referring the Speaker’s condition (line 2), the second to his mindset (line 10), and the third, the state of a monarch, can be read to mean a country or kingdom (line 14). SONNET 73 That time of year thou mayst in me behold mayst=you may When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang Upon those boughs which shake against the cold, Bare ruin'd choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. In me thou seest the twilight of such day As after sunset fadeth in the west, Which by and by black night doth take away, Death's second self, that seals up all in rest. In me thou see'st the glowing of such fire That on the ashes of his youth doth lie, As the death-bed whereon it must expire, Consum'd with that which it was nourish'd by. This thou perceivest, which makes thy love more strong, To love that well which thou must leave ere long. That time of year:late autumn or early winter; thou late=lately thou seest=you see fadeth=fades doth=does whereon=on which that: i.e., the poet's desires. thou perceivest=you perceive that: the poet's youth and passion (or the speaker); ere long=in a short time PARAPHRASE In me you can see that time of year When a few yellow leaves or none at all hang On the branches, shaking against the cold, Bare ruins of church choirs where lately the sweet birds sang. In me you can see only the dim light that remains After the sun sets in the west, Which is soon extinguished by black night, The image of death that envelops all in rest. I am like a glowing ember Lying on the dying flame of my youth, As on the death bed where it must finally expire, Consumed by that which once fed it. This you sense, and it makes your love more determined Causing you to love that which you must give up before long. SUMMARY In the first quatrain, he tells the beloved that his age is like late autumn, when the leaves have almost completely fallen from the trees, and the weather has grown cold, and the birds have left their branches. In the second quatrain, he then says that his age is like late twilight, when the remaining light is slowly extinguished in the darkness, which the speaker likens to “Death’s second self.” In the third quatrain, the speaker compares himself to the glowing remnants of a fire, which lies “on the ashes of his youth”—that is, on the ashes of the logs that once enabled it to burn—and which will soon be consumed “by that which it was nourished by”—that is, it will be extinguished as it sinks into the ashes, which its own burning created. In the couplet, the speaker tells the young man that his love must be strengthened by the knowledge that he will soon be parted from the speaker. ANALYSIS Sonnet 73 develops the theme of old age through a sequence of metaphors expressing the narrator's own anxiety over growing old. Each quartrain compares the narrator's "time of year" (i.e., stage of life) with various examples of the passing of time in nature. The metaphors shorten in duration from months to hours to minutes, the acceleration itself a metaphor for the increasingly rapid speed of old age on the human body. In the first quatrain, the narrator compares himself to the late autumn season, that time of year when the trees have begun to lose their leaves and the cold is setting in. Quatrain two makes life still shorter, going from the seasons of the year to the hours of the day. The narrator is at the twilight of his life: his sun has set, and Death is soon upon him. But even so, the emptiness of death is not fully established until quatrain three, where it is finally understood by the narrator as something permanent. Whereas the changing of the seasons and the passing of day and night occur in infinite cycles, a fire is not reborn from its ashes, and its extinguishment means the end. Time is the enemy; Time is Death. The passing of time is the creator and the destroyer of life. With that said, the closing couplet of sonnet 73 is like an admonition: one's love should grow stronger as one's time left to love is running out. It is not entirely clear whether this line is addressed specifically to the fair lord or in fact to himself, or perhaps even to both. In any case, the narrator is clearly distressed by his inevitable fate: old age, death, and eternal separation from the fair lord. SONNET 130 (see textbook) l.3 dun: i.e., a dull brownish gray. l.5 roses damasked, red and white: This line is possibly an allusion to the rose known as the York and Lancaster variety, which the House of Tudor adopted as its symbol after the War of the Roses. The York and Lancaster rose is red and white streaked, symbolic of the union of the Red Rose of Lancaster and the White Rose of York. l.8 than the breath...reeks: i.e., than in the breath that comes out of (reeks from) my mistress. As the whole sonnet is a parody of the conventional love sonnets written by Shakespeare's contemporaries, one should think of the most common meaning of reeks, i.e., stinks. Shakespeare uses reeks often in his serious work, which illustrates the modern meaning of the word was common. l.13 rare: special. l.14 she: woman. l.14 belied: misrepresented. l.14 with false compare: i.e., by unbelievable comparisons. QUESTIONS 1. In this sonnet the beloved woman is described through several comparisons. Underline them and think what kind of effect they produce in the reader. 2. Look at the turning point of the poem. What are the two words that introduce it? 3. Now focus on the statement expressed in the final couplet. Is it in line with the rest of the poem or does it contradict it? What is the adjective used to describe his love? ANALYSIS In Sonnet 130, one of the most famous of the dark lady sequence, Shakespeare appears to be criticising the idealising tendency of most Elizabethan love poetry to compare the beloved to the glories of nature, inspired by Platonic notions of beauty. All the comparisons he makes are negative. Sonnet 130 is one of the few of Shakespeare's sonnets with a distinctly humorous tone. Its message is simple: the dark lady's beauty cannot be compared to the beauty of a goddess or to that found in nature, but to the speaker she is as rare as any other other beautiful woman idealized in poetry. The sonnet is generally considered a humorous parody of the typical love sonnet made popular by Petrarch and, in particular, made popular in England by Sidney's use of the Petrarchan form in his epic poem Astrophel and Stella. Petrarch, for example, addressed many of his most famous sonnets to an idealized woman named Laura, whose beauty he often likened to that of a goddess. In the sonnets, Petrarch praises her beauty, her worth, and her perfection using an extraordinary variety of metaphors based largely on natural beauties. Likewise, in Sidney's work the features of the poet's lover are as beautiful and, at times, more beautiful than the finest pearls, diamonds, rubies, and silk. In Shakespeare’s day, these metaphors had become the accepted technique for writing love poetry. In stark contrast, in Sonnet 130, Shakespeare makes no attempt at deification of the dark lady; in fact, the references to such objects of perfection are indeed present, but they are there to illustrate that his lover is not as beautiful. He explicitly states that his mistress is not a goddess. Yet, though she is not as beautiful as things found in nature, the narrator ends the sonnet by proclaiming his love for his mistress and in the closing couplet says that in fact she is just as extraordinary ("rare") as any woman described with such exaggerated or false comparisons. The rhetorical structure of Sonnet 130 is important to its effect. In the first quatrain, the speaker spends one line on each comparison between his mistress and something else (the sun, coral, snow, and wires). In the second and third quatrains, he expands the descriptions to occupy two lines each, so that roses/cheeks, perfume/breath, music/voice, and goddess/mistress each receive a pair of unrhymed lines. This creates the effect of an expanding and developing argument, and neatly prevents the poem from becoming stagnant. Beauty and Love The second, much smaller group of sonnets that Shakespeare wrote are address to a ‘dark lady’ whose real identity remains a mystery. These poems rejects many of the traditional conventions of Elizabethan love poetry, such as that of exhalting the’ideal perfection and beauty of the beloved. In some ways in fact, they represent a critique of such conventions. In describing his dark lady, Shakespeare is careful to emphasise how little she corresponds to the conventional ideas of beauty. But this is not the same thing as the natural beauty of flowers or of the sun, moon or stars to which other poets falsely compare their ladies. It is rather, the beauty of her own particular nature in all its uniqueness and difference. Unlike many other women, who use the artefices of make-up to hide their defects and try to reach some ideal perfection, the dark lady is content to stay ‘as nature intended her’. Her ‘naturalness’ also makes her extremely ‘rare’ in a world in which the desire of other women to correspond to an ideal notion of beauty makes them all banally similar – inferior copies of an unattainable ideal. What fascinates the poet in his lady are the things that make her unique in his eyes. Often, in fact, it is her apparent imperfections that distinguish her from the norm. These range from physical defects to moral one: her lack of virtu, her infidelity, her cruelty. Tha dark lady sonnets represent a much more honest, real account of a love affair than any other poems from the period. Here we have love in all its colours, from lust to tenderness, shame to disgust, adoration to hatred, irony to despair and jealousy to indifference. For the poet, the dark lady is at the same time an angel promising infinite happiness and a demon sent to drive him mad. ANALYSE THE FOLLOWING SONNET BY SHAKESPEARE: SONNET 71 No longer mourn for me when I am dead PARAPHRASE You can mourn for me when I am dead, but no longer Then you shall hear the surly sullen bell Give warning to the world that I am fled From this vile world, with vilest worms to dwell: Nay, if you read this line, remember not The hand that writ it; for I love you so That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot If thinking on me then should make you woe. O, if, I say, you look upon this verse When I perhaps compounded am with clay, Do not so much as my poor name rehearse. But let your love even with my life decay, Lest the wise world should look into your moan And mock you with me after I am gone. Than when you hear the solemn-sounding bell Announce to the world that I have gone From this vile world, to live with the worms (in the grave): If you read this line, do not remember The hand that wrote it; for I love you so much That I would rather you forget me completely If thinking about me when I am gone would make you upset. O, if you look upon this sonnet When my body has become mixed with the dust and dirt, Do not even mention my insignificant name. But let your love decay in the same way that my life rots away, So that the malicious people in world do not pry into your grief And use your relationship with me to mock you after I am dead.