(YOUR TITLE)

African American Vernacular English

BY

Aya Kawahara

A FIVE PAGE PAPER

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF

THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE COURSE OF

SEMINAR 1 (World Englishes)

Kumamoto Gakuen University Foreign Language Department

English Course

SUPERVISOR: Judy Yoneoka

Kumamoto Gakuen University

Oe 2-5-1 Kumamoto

Japan

January 17 th , 2005

This paper consists of approximately 1000 words

1

Outline

1.

Introduction

2.

Background of Black American English.

2.1 Black American English, who speaks it?

2.2 Historical background

3.

Phonetic differences

3.1 Vowels

3.2 Consonants

4.

Grammar differences

5.

Conclusion

2

Abstract

現在、世界中で代表的な言語として使用されている英語において、特定の民族が

話す英語に着眼し、この論文ではアフリカ系アメリカ人すなわち主に黒人が使用する

といわれている英語について研究した。

1.

Introduction

In the modern world there are many different kinds of Englishes. They are different because there are different age, gender, race, social classes, religions, and etc. Black English is one of the most well known dialects in the world because of rap and hip-hop music. Also it is spoken by a specific race, it has a long history in its background. This paper will concentrate on

Black American English.

In the modern world, there are many different races. As you all know,

English is spoken all over the world. The speakers of English are not one race; many different ethnicities speaks English. Sometimes members of a particular minority ethnic group have their own way of speaking English depending on their culture of background. This is called a minority dialect.

Examples are African American Vernacular English in the USA, London

Jamaican in Britain, and Aboriginal English in Australia. In this paper, we will mainly talk about African American Vernacular English.

African

American Vernacular English is known as Black English and is sometimes also called Ebonics outside of Study field.

According to H. Clegg (1997), many African Americans do not speak

Standard English. They speak their own way of English, which is AAVE.

AAVE evolved in America as a result of adaptation of English to an African language system. The number of AAVE speakers has not been clearly counted, because a variety of speakers exist. Some uses phonetical AAVE, some use grammatical AAVE.

2.

Background of African American Vernacular English.

In the following sections, we will talk about the background of African

American Vernacular English. We will talk about who uses this language, and historical background of this language.

3

2.1

Black American English, who speaks it

First of all, AAVE is known as Black American Vernacular for linguists and also known as Ebonics outside of academic fields. It is easy to understand that Black people use this language, but nowadays, not only Black people but also other ethnic groups use this language. Especially hip hop musician and music have a great effect on the English of the young generation.

Also, it is usual that if one lives in a place where people speak different language than their language, they will adapt their way of speaking language.

However, Black Americans do not adopt Standard English. Why? It has deep relation to its historical background.

2.2

Historical background

The history of AAVE goes back to a time when slaves existed.

Some scholars contend that AAVE developed out of the contact between speakers of West African languages and speakers of vernacular English varieties. West Africans learned English on plantations in south coast states; where there were many slaves traded, from a small number of native speakers. South coast states are Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and so on.

At that time, West Africans had limited access to English because only a small number of native speakers existed around them. Therefore they had to learn English by themselves. This is why AAVE has such characteristics.

3.

Phonetic differences

Like other English dialects, AAVE also has its own way of pronunciation.

As most of you know, when you hear black people speak English, it is very different from Standard English. This section will focus on Vowels and consonants differences. There are lots of pronunciation differences, but this paper will only introduce a few facts.

4

3.1

Vowels

When a nasal follows a vowel, AAVE speakers usually delete the nasal consonant and nasalize the vowel. This nasalization is written with a tilde

( ~ ) above the vowel. So 'man' becomes mã.

In AAVE the vowel in 'night' or in 'my' is often not a diphthong. So when pronouncing the words with this diphthong, AAVE speakers (and speakers of

Southern varieties as well) do not move the tongue to the front top position.

So 'my' is pronounced ma as in he's over at ma sister's house.

AAVE has a unique way of stress in its language pronunciation. So, where words like police, hotel and July are pronounced with stress on the last syllable in Standard English, in AAVE they may have stress placed on the first syllable so that you get po-lice, ho-tel and Ju-ly.

3.2

Consonants

In AAVE English, they are likely to reduce the consonants in the word.

When two consonants appear at the end of a word, they are often reduced.

If the next word starts with a consonant, it is more likely to be reduced than if the next word starts with a vowel.

At the beginning of a word, the voiced sound is regularly pronounced as

/d/ so 'the', 'they' and 'that' are pronounced as /de/, /dey/ and /dat/.

This is a very common feature of AAVE in which 'think' is regularly pronounced as tink, and so on. When the th sound is followed by r, AAVE pronounce the th as f as in froat for 'throat'.

4.

Grammar differences

In AAVE language, they also have their own way of grammar. It is slitelly different from Standard English.

5

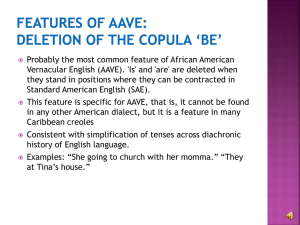

In AAVE, they tend to reduce the “be” verb. Here are some examples below (Language Varieties, April, 2004).

1

In sentences with gonna or gon:

I don't care what he say, you __ gon laugh. 2

Before verbs with the -ing or -in ending(progressive):

I tell him to be quiet because he don't know what he __ talking about.

I mean, he may say something's out of place but he __ cleaning up behind it and you can't get mad at him.

3

Before adjectives and expressions of location:

He __ all right.

And Alvin, he __ kind of big, you know?

She __ at home. The club __ on one corner, the Bock is on the other.

4

Before nouns (or phrases with nouns)

He __ the one who had to go try to pick up the peacock.

I say, you __ the one jumping up to leave, not me.

5

AAVE uses ain't to negate the verb in a simple sentence. In common with other nonstandard dialects of English, AAVE uses ain't in standard English sentences which use "haven't". Here are some examples below.

I ain't step on no line.

I said, "I ain't run the stop sign," and he said, "you ran it!"

I ain't believe you that day, man.

6

1 Sydnell, Jack. Language Varieties African American Vernacular English , Available on the Internet, http://www.une.edu.au/langnet/aave.htm

, June 8th, 2004.

2 Ibid

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

6

AAVE also has a special negative construction which linguists call

"negative inversion". An example from Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon follows:

Pilate they remembered as a pretty woods-wild girl "that couldn't nobody

put shoes on."

In this example, a negative couldn't is moved in front of nobody. Further examples are below.

Ain't no white cop gonna put his hands on me.

Can't nobody beat 'em

Can't nobody say nothin' to dem peoples!

Don' nobody say nothing after that. (Ledbetter, born 1861)

Wasn't nobody in there but me an' him. (Isom Moseley, born 1856)

There are lots more grammar differences in AAVE, but in this paper we discuss just a few.

5.

Conclusion

Today, many school teachers try to “fix” childrens who speak AAVE.

However, after researching about this language, it made it clear that AAVE has its own history and people who speak this language show respect to his/her ethnicity. In Japan we also have many different kind of dialect depend on geographical facts. People try to hide their dialect when they go to different place, but after writing this paper, it made me realize that it is not a shame to have our own dialect.

Bibliography

Gordon, Lynn (2003) General Differences between SAE and AAVE,

available on the internet, http://www.wsu.edu/~gordonl/S2003/326/SAE_AAVE.htm

June 30th,

2003.

Ito, K. (1982) Eigogaku to Eigo kenkyuu. (English Linguistics and English

Research) Tokyo: Nanunsya

Legrand H. Clegg II, Editor & Publisher. Volume I, Edition II, http://melanet.com/clegg_series/ebonics html January 1997.

7

McLucas, Bryan (2003) African American Vernacular English, Available on the Internet. http://www.arches.uga.edu/~bryan/AAVE/ June 27 th ,

2003.

Patrick, Peter L. (2001) African American English: A Webpage for

Linguists (and other folks) Available on the Internet, http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~patrickp/AAVE.html , June 5, 2003

Sydnell, Jack. Language Varieties African American Vernacular English,

Available on the Internet, http://www.une.edu.au/langnet/aave.htm

,

June 8th, 2004.

Takahasi, T. (1993) America Eigo (American English, in Japanese). Tokyo:

The Simul Press.

Tottie, Gunnel. (2002) An Introduction to American English.

Massachusetts: Blackwell.

8