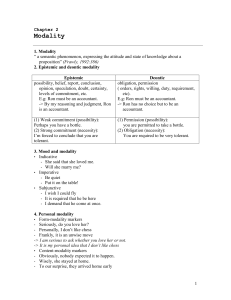

possibility notion

advertisement

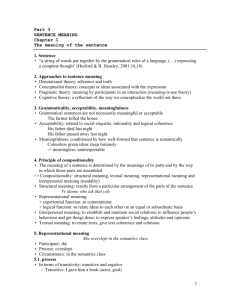

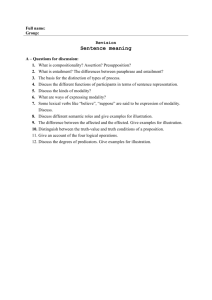

MOOD AND MODALITY Asist. univ. Ioana Cotîrlea Univ. "1 Decembrie 1918", Alba Iulia. 1.1. Towards a definition of modality This notion of modality is vague and leaves open a number of possible definitions, though something along the lines of Lyons (1977:452) - option or attitude of the speaker - seems promising. In order to better understand the notion of modality we should make first a distinction between propositions and modality. Jespersen (1924:313) talked about the contents of the sentence and Lyons (1977:452) about the proposition that the sentence expresses, both wishing to distinguish them from the speaker`s attitude or opinion. This assumes that a distinction can be made in a sentence between modality and proposition. This distinction is very close to that of locutionary act and illocutionary act as proposed by Austin (1962:98). In locutionary act we are saying something, while in the illocutionary act we are doing something - answering a question, announcing a verdict, giving a warning or making a promise. The proposition is assertable; the contents of the assertion can be questioned, denied or supposed, and can be entertained in other moods as well (Lewis, 1946:49). In Fillmore (1968:1-88) we find a proposal which is similar to Lyons (1968). Sentences have a basic structure composed of a proposition - a tenseless relationship involving verbs and nouns, and of a modality constituent, separated from the first and including negation, tens, mood, aspect and some sentence adverbials. 1.2. Types of modality Modality is the category by which speakers express attitudes towards the event contained in the proposition. The attitude may be that of assessing the probability that the proposition is true in terms of modal certainty, probability or possibility. This is epistemic (or extrinsic) modality (Downing and Locke, 1992:382). By means of modality speakers can intervene in the speech event by lying obligations or giving permission. This is intrinsic or deontic modality. Closely related to these meanings are those of ability and intrinsic possibility. Therefore modality may range from possibility to absolute certainty, in the case of epistemic modality, and from permission to obligation, in the case of deontic modality. By means of these two main kinds of modality, speakers can carry out two important communicative functions: (a) to comment on or evaluate an interpretation of reality (epistemic modality) (b) to intervene in, and bring about changes in events (deontic modality) 1.3. Means of expressing modality The modal auxiliaries in English express both types of modal meanings (epistemic and deontic). But there are, in addition, other forms available for the expression of particular modal 173 meanings. 1.3.1. Verbs expressing modal meanings 1.3.1.1. Modal auxiliaries: can/could may/might shall/should will/would must ought to have to semi-modals: need and dare 1.3.1.2. Modal lexical verbs: allow beg command forbid wander wish guarantee guess promise warn 1.3.1.3. Multi-word verbs: have got to be bound to be to 1.3.2. Other means of expressing modality 1.3.2.1. Modal disjuncts: probably possibly surely hopefully thankfully obviously etc. 1.3.2.2. Modal adjectives: possible probable likely used in constructions such as: It`s possible he may come, or as part of a nominal group, as in a likely winner of this afternoon`s race or the most probable outcome of this trial. 1.3.2.3. Modal nouns: possibility probability chance hope likelihood There`s just a chance that he may come. 1.3.2.4. Certain uses of if-clauses as in: If you know what I mean. If you don`t mind my saying so. 173 What if he`s had an accident? 1.3.2.5. The use of the remote past as in: I thought I`d go along with you, if you don`t mind. 1.3.2.6 The use of non-assertive items such as any in: He`ll eat any kind of vegetable. 1.3.2.7. Certain types of intonation, such as the fall-rise 1.3.2.8. The use of hesitation phenomena in speech 1.4. Mood and Modality We are using mood as a category of grammar and modality as a category of meaning; the distinction is then similar to that between tense and time, gender and sex, number and enumeration. The term mood is traditionally restricted to a category expressed in verbal morphology; it is applied only to the grammatical system of verb and verb phrase. It is formally a morphosyntactic category of the verb, like tense and aspect, even though its semantic function relates to the contents of the whole sentence. Yet modality is not expressed only within the verbal morphology. It may be expressed by modal verbs as well as by lexical items. Lyons (1968:307) suggests that we can define mood in relation to an "unmarked" class of sentences which express simple statements of fact; as for modality he says that a particular language may have 'a set of one or more grammatical devices for "marking" sentences according to the speaker`s commitment with respect to the factual status of what he is saying. Thus mood is essentially grammatical, such that Latin has subjunctive mood, while modality relates to the speaker`s commitment. Recently he has distinguished mood and modality in that mood involves "the grammaticalization of modality". 173 173