si545-w13 - University of Michigan

Video Translation Project: Subtitles for Learning

Final Report

Caitlin Barta

Vibha Mehta

SI 545

May 1, 2013

License: Unless otherwise noted, this material is made available under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution 3.0 License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

1

Table of Contents

Toolkit Challenge: Time-consuming to manually add translators to each video ..................18

Toolkit Challenge: Lack of a system to track progress of all videos in one place ................18

Toolkit Challenge: Lack of mechanisms to handle multiple translators for the same video .20

2

Introduction

One of the UN Millennium Development Goals is to “make available the benefits of new technologies – especially information and communication technologies.” It has become easier to spread the benefits of ICT, particularly to development issues, because of low cost of computing, increased availability of wireless communications, and the emergence of a more supportive business environment (Brewer et al, 2005). With the world becoming increasingly interconnected, the need for communication across languages is magnified.

The Internet has become a global resource, and yet approximately 55% of content is written in English (W3Techs, 2013). However, English speakers were estimated to make up only 27% of Internet users in 2011 (Smartling, 2013). This percentage has actually decreased in recent years, partially due to the fact that the number of non-English speaking users has greatly increased. Notably, 24% of Internet users are from China as of 2011, but in contrast, Chinese content only made up 4.5% of the web. Similarly, India is the second most populous country in the world; however, it is estimated that less than 1% of website content is in an Indian language such as Hindi or Tamil (W3Techs, 2013). As it stands, non-

English speaking populations cannot take advantage of much of the content on the web.

From Take I to Take II

Our first approach to a translation project was to create a crowd-sourcing initiative to facilitate translations of any video into any language desired. We reached up to the paper prototyping stage with this concept. Some of the features we intended for this website to include were the ability to browse videos being translated and request new videos to be translated. At this stage, we started to consider working with Amara, an existing translation tool, in some way.

However, as we moved forward with the idea, we faced difficulties regarding the scope of the project and the legalities associated with Internet copyright law. Following a meeting

3

with the Language Resource Center and Open.Michigan, we found that a more feasible project was to collaborate with Open.Michigan on its initiative to make the University’s educational resources more accessible. Our motivation for the translation project was driven by the potential of open access, and their initiative was therefore aligned with our goals.

Take II - Open.Michigan Video Translation Initiative

Open.Michigan is a University of Michigan initiative that enables faculty, students and others to share their educational resources and research with the global learning community. Considering the extent of globalization, it is imperative to make educational content available in multiple languages to increase its accessibility. Open.Michigan attempts to address this need via a crowdsourcing translation project headed by Kathleen

Ludewig Omollo.

The pilot run of the project aimed to have 12 clinical microbiology videos and 19 disaster management videos translated into 4 priority languages (French, Portuguese, Spanish, and

Swahili), as well as 31 other languages. The microbiology videos were co-authored by professors at University of Michigan and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and

Technology in Ghana in 2009; the 19 disaster management videos were jointly authored in

2009-2012 by the East Africa Health Alliance, Johns Hopkins University, and Tulane

University, with some formatting and publishing support from the University of Michigan.

As of late March 2013, 70 caption tracks were completed, including 28 in Spanish, 16 in

Portuguese, 14 in French, 7 in Russian, 2 in Danish, 2 in Swahili, and 1 in Luganda.

Our project finally evolved into an effort to help Open.Michigan crowd source translations for its videos and captions more efficiently, particularly focusing on the management side.

4

Needs Analysis

To thoroughly understand the needs for our project, we conducted detailed interviews with

Open.Michigan and the Language Resource Center. Our findings are discussed below.

Project Setup

Kathleen first had to set up the Google Translate Toolkit for the volunteer translators. Each language for every video has its own page in the toolkit. For example, a video with 35 requested languages will require 35 separate links to be created, each pointing to a Toolkit page for that video in that specific language. This process was done for all 31 videos and was a very time-consuming process. The next step was to get volunteers to participate and translate the videos.

Current Signup Process

The steps of the current signup process are outlined below:

1.

Open.Michigan creates a Google signup form

2.

This link is distributed to interested volunteers

3.

A translator signs up by indicating what videos and language(s) they are interested

4.

Open.Michigan gets a notification the form was submitted

5.

Adds the translator to the selected video(s) and corresponding language track(s)

6.

Also adds name on aforementioned Google Doc next to each link in order to track contributors

7.

Sends email to volunteer with link(s) to translation interface for each caption and to the Google Doc

If a volunteer wants to translate a video into multiple languages, they must be added individually to each language track, e.g. volunteering for 3 videos in 3 languages requires that person to be added 9 times. The largely manual management process is unwieldy and unsustainable if project is to be scaled up, i.e., more videos are added for translation.

5

Challenges

From our interviews, we found the following challenges of the signup process, from the management perspective:

Time-consuming to manually add translators to each video:

This was expressed by Open.Michigan. As seen earlier, once a translator signs up to translate, he or she has to be manually added by Open.Michigan to each video and caption track for them to begin. This is tedious, especially if one translator signs up for multiple videos or multiple languages, as they must be added individually to each.

Lack of a system to track progress of all videos in one place:

This was also expressed by Open.Michigan. Each video’s language track has its own dedicated Google Translator Toolkit link, but the management interface names all the links identically. It is impossible to distinguish one language from another for the same video, and one has to click on each individual link to see the progress that has been made on the translation. Naturally, a single page displaying translation progress on all videos would be convenient for tracking purposes.

Lack of mechanisms to handle multiple translators for the same video:

When the translators were selecting videos on the signup page, there was no automated system that flagged a video with multiple translators. Open.Michigan needed to check the progress of the translation manually; if it was completed already, they had to ask the new translator via email if they were interested in another video. Both the Language Resource

Center and Open.Michigan expressed the desire for a mechanism that makes the signup process less manual and prevents translators from signing up for a completed video.

6

Lack of a vetting/proof reading mechanism to ensure quality of translations:

This was expressed primarily by the Language Resource Center during our needs analysis.

Since there is no mechanism to collect information about the translators’ language skills and proficiency, there is no way to identify if a particular translation is good or poor. So, collecting this information from translators, perhaps when they sign up, would be useful to gauge the quality of the translation and need for further editing.

Current Translation Process

Once a translator has signed up, the following are the steps of the actual translation process:

1.

Locate desired video on the Google Doc or via email from Open.Michigan

2.

Link takes the translator to Google Toolkit or Amara, depending on the language

3.

Volunteer finishes translating and submit to publish

4.

Open.Michigan receives notification about the completion of the translation

5.

Open.Michigan reviews the translation,

6.

Then credits translator in video description and publishes the new translation

7.

Open.Michigan manually updates the status to ‘done’ on the Google Doc and their tracking spreadsheet

To thoroughly understand the translator’s side of the process, we conducted an interview with a translator. His experience with the translation process was good, with largely positive feedback regarding the difficulty of the process. A key takeaway from this conversation was the need to include external, topical resources, as most videos were technical in nature, and we found that he and other translators often relied on other resources for the technical language.

7

Follow-up Survey

We also conducted a survey follow-up with those who had completed at least one video caption. Questions covered topics such as:

● Languages translated into

● Use of a non-English keyboard

● Helpfulness of the machine translation

● Difficulty level of translating the Open.Michigan videos

● Any difficulties encountered during sign up or translation

● Other comments

We received 17 responses out of the 25 survey recipients, a 68% response rate. We found no major common difficulties in signups or translating. Below, we highlight some of our major findings.

Use of non-Latin keyboards

Yes – 9 (53%)

No – 8 (47%)

We learned that participants used a variety of methods to type their translations, including shortcuts, virtual keyboards, and in at least one case, copy-pasting special characters. Were we to revise the question, we would prefer to ask what method(s) translators used to type their translations and make it a multiple choice question in order to segment and clarify responses. However, we were still able to find that responses varied, and that perhaps recommending a tool such as Google Input Tools to translators would be useful, especially

8

for those copy-pasting characters or who are otherwise uncertain how to insert special characters.

Helpfulness of machine translation

Very helpful - 5 (29%)

Helpful - 8 (47%)

Neither – 1 (17%)

Unhelpful – 2 (12%)

Very unhelpful

– 0 (0%)

N/A – 1 (6%)

The majority of respondents found the machine translations helpful, although there were a few complaints in the expanded response area. The consensus was that it made translation faster, but that correction was needed for contextual sensitive words and phrases.

Ease of translation

Quite difficult - 0 (0%)

Somewhat difficult - 2 (12%)

Average – 9 (53%)

Somewhat easy – 5 (29%)

Very easy – 1 (6%)

Most said translating was of average difficulty or somewhat easy. However, reading the comments reveals that some expected some level of difficulty, especially with regards to the technical language. In the future, we might reword this question to: “Compared to how long you expected translation to take, how much time did you spend translating?” It is natural for respondents to admit that something is difficult, and difficulty is also a

9

subjective concept. “Difficult” also has a negative connotation; using “challenge” in its place might have put the question in a more positive light.

Design Process

Initial Open.Michigan Prototype

Based on the needs analysis, we thought it was best that our project simplify the management process, add the ability to browse videos on one page, and collect information on language skills. Therefore, we first created a dedicated page on Open.Michigan for videos. This page allows users to browse for videos on one place, watch the video before signing up to translate, and incorporates a more extensive search feature. We also added features such as topical resources and dictionaries to aid the translation process.

We included a link to a Google Form at the top of the page to collect user information similar to the form currently used by Open.Michigan. Our addition to the form was to collect language skills and proficiencies of the translator – useful information for quality control purposes. Once the user has browsed, watched and selected a video to translate, he or she is taken directly to the Amara website to do the actual translation.

10

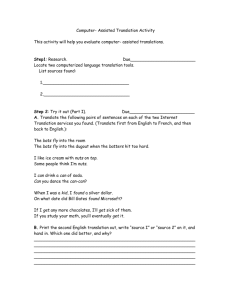

Screenshot of Prototype V1

Our solution to simplify the management process was to use Amara for all translations.

Most of Amara’s features were well-aligned with Open.Michigan’s needs; it allows viewing the translations in-progress on one page with information on time of last edits, users who made the edits, and the languages in-progress.

Usability Test

The next step of our project was to test the prototype including Amara with five users. The results are discussed below.

11

Open.Michigan Prototype

Search box: All users’ first instinct to find a video to translate was to look for the search box.

We had not placed it as prominently as users needed, so we took that into consideration for the subsequent version of the prototype.

Google Form: Two of the users missed seeing the Google form entirely, thus creating the need to modify the form and reduce the text around the link.

General: The overall feedback was that the page was too ‘busy’ and the browsing was confusing. We took both into consideration when modifying the website for the next version.

Amara

The general feedback for Amara was that it is easy to use, relatively simple interface, but that the timed subtitles popup was intimidating.

Modifications to Prototype

Based on our feedback from the usability testing, we made several changes to our Axure prototype.

12

Screenshot of Prototype V2

Aesthetics and Simplicity

The original page was described as “busy” by participants more than once, so aesthetics and simplicity were qualities we wanted to focus on. One minor change, which deviated from the Open.Michigan websites style guide slightly, was de-bolding the filters on the lefthand side of the page. Second, buttons originally placed below the videos led to the translation interface; these were replaced with text links featuring the title of the video.

The third change regarded the introductory text at the top of the page, which had taken up a significant portion of the page in our initial prototype. We removed much of this text in the second iteration. We also moved the search box from its original position to sit directly above the videos; due to the gestalt principle of similarity, this more clearly defines the search box and the videos as belonging to the same group (Soegaard, 2010).

13

Resources

We removed the right-hand column titled “Resources” and instead incorporated links to additional resources below a very short introductory statement. Links to “Frequently asked

Questions,” “Translation Best Practices”, and “Helpful Resources” give supplemental information to translators and visitors to the page. Ideas of sample questions for the first two pages can be found below; “Helpful Resources” is currently a catch-all for links to helpful resources like dictionaries or other trusted sources of material that may be helpful for translators.

Prototype V2 – Frequently asked Questions

14

Prototype V2: Translation Best Practices page

Skills Survey Integration

We originally had a separate link featured in the introductory text to a brief form meant to gather information from new translators regarding their skills. In the second iteration, we integrated better into the flow of the website. When the user selects a video to translate, the back-end of the website would check if the user was logged in had completed the skills survey. If not, it would direct the translator to login if necessary and then fill out the form, before being redirected to the translation interface for the video they selected. Without requiring user accounts, another way to track whether a user had already completed the survey might be through a cookie; however, cookies are not a permanent solution. If cleared from the browser or another browser were used, the translator would be again shown the skills form. This would result in a very poor experience, which is why our current design requires a user account.

15

Amara On-Campus

On April 2, 2013, two representatives from Amara gave a talk on-campus at the University of Michigan. We were able to ask them questions about the product both during and after the presentation. We also were able to get their contact information and have since been in touch with questions as they have arisen.

A major point of contention for Open.Michigan was that YouTube provided machine translations, where it appeared Amara did not. However, upon further investigation, Amara supports “auto-translation” via Bing for any video that has a transcript uploaded. In the

Amara translation interface, an auto-translate button fills in any empty fields with a machine translation from the origin language into the target language. The difference between the two sites’ approaches is that YouTube automatically fills in all fields with machine translations, whereas Amara allows the user to decide when to use the autotranslate feature. Also, YouTube utilizes Google Translate, while Amara currently uses Bing

Translate. It is unclear at this time how different the quality of the machine translations are between the two services, an issue that can be evaluated as time goes forward.

Another question we had regarded entering characters that are non-Latin or contain diacritics. In the Google Translate Toolkit, Google’s Input Tools are incorporated, which makes it relatively easy to enter such characters via transliteration or a virtual keyboard without installing additional software or utilizing extra hardware. We had concerns that since Amara did not incorporate alternate keyboards into its interface, this would be a serious drawback. However, we found that Google has created a Google Input Tools extension for Chrome. This means that the Google Translate Toolkit and Amara are on similar footing with regards to support for non-Latin and diacritics. For users who do not have the appropriate keyboards installed, Open.Michigan can recommend users install

Chrome with the Input Tools extension. While this is an extra step, we believe it is not an obstacle which puts Amara at a serious disadvantage in comparison to its competitor.

16

Amara with Google Input Tools Spanish keyboard visible

Lastly, we had several questions around the idea of distributing tasks and the review process. Currently, Open.Michigan must approve translations before they are displayed on

YouTube. It was unclear whether Amara supported that feature, but from the presentation and follow-up questions with Amara, we found that this is still possible with Amara

Enterprise. Furthermore, tasks can be distributed among members of a translation team, a feature currently unavailable in the Google Translate Toolkit. Teams can be created, either open or closed membership, and translating, editing, and reviewing tasks can be assigned if desired. Amara is also working on a second version of their software, which promises to bring even more collaborative features, although details of this functionality were not yet disclosed.

17

Recommendations for the Video Translation Initiative

If Open.Michigan plans to expand its video translation, we recommend that Open.Michigan move from using the Google Translate Toolkit in YouTube to Amara. We also recommend that Open.Michigan create a dedicated presence on its website for the project as demonstrated by our prototype. Our reasoning for these recommendations follows.

Challenges and Solutions

Toolkit Challenge: Time-consuming to manually add translators to each video

Amara does not require volunteers to be added to each video and individual caption track.

Volunteers can navigate to a video page, then select what language they wish to translate to and immediately start translating. Open.Michigan does not currently review applicants before adding them to videos.

Toolkit Challenge: Lack of a system to track progress of all videos in one place

Amara aggregates all videos together in one place and displays how many translations by language are in progress. Once a video is selected, users can view a page which shows progress by language, as well as an “Activity” tab that displays the edit history of the video’s translations.

18

User profile page aggregates all videos with # languages active for each

Amara video page showing subtitle progress in bottom-left

19

Toolkit Challenge: Lack of mechanisms to handle multiple translators for the same video

We found that Amara’s platform clearly shows the progress of the video’s translation when the user signs up. From our attendance at the Amara talk on campus, we also learned that if the Enterprise version is configured a certain way, it can also highlight what stage the videos are at (e.g. in need of translation, editing, etc.) and what still needs to be completed.

While multiple translators can sign up for a video, it is clearer if additional translation needs to be done or if editing should be completed.

Toolkit Challenge: Lack of a vetting/proof reading mechanism to ensure quality of translations

In our prototype, we incorporated a form designed to gather the translator’s language skills, which would appear when the user selects a video to translate if the system does not have a skills record for that translator yet. Unfortunately, Amara does not incorporate the proficiency level of the translator when it asks what languages they are experienced with, but they recommended that we suggest users enter that information on their Amara profile as an alternative.

Implementation Challenges

Switching to Amara Enterprise

We found many advantages of switching from the Google Translate Toolkit to Amara on the management side of the process. There is no need to add translators individually; progress is much more easily tracked, and edit histories of each video’s translations are readily accessible. Owners can even revert to an earlier version of a translation if changes were made that negatively affect the quality of the translation. The team creation feature of

Amara Enterprise would allow Open.Michigan to build an Open.Michigan translation team, with all videos and their progress in one place. If desired, Open.Michigan could even distribute tasks among the team, such as translating, editing, or reviewing.

20

However, we do note two challenges to the switch from using the Google Translate Toolkit in YouTube to Amara. The first is that the Enterprise version would require a monetary investment, although we do not have a price quote at this this time. The free version of

Amara is also available; however, it does not allow the creation of teams or the distribution of tasks. Second, the current process for syncing existing translations that are in YouTube with Amara may cause some conflicts, though we believe them to be minimal. When syncing Amara and YouTube, all finished translations are pulled into Amara. Translations that are completed on Amara get pushed to YouTube once completed. However, if a translation is partially completed in the Toolkit, it is possible that it will be ignored by

Amara, and all further translating will need to be completed in Amara. However, if

Open.Michigan directs their translators to Amara going forward, this problem should not be critical.

Creating a project presence on Open.Michigan website

We believe that creating a project presence on the Open.Michigan website will be beneficial for several reasons. One, it creates a hub where all volunteers and visitors can view the videos or sign up to translate. Also, any information related to the project can be housed here, instead of being just on the Open.Michigan blog. This could be good for both marketing, publicity, and for drawing volunteers.

However, we recognize some challenges in implementation exist. First, it would be necessary to integrate the Amara API with existing metadata in Open.Michigan’s database.

We want to maintain a similar search and browsing system to the one already utilized by

Open.Michigan, although we do want to combine the two so as to allow people to view videos by topic, similar to browsing for courses. This integration with the API, along with the coding of the backend, frontend, and any required database changes, could pose challenges and require a non-trivial time investment.

21

We also recognize challenges with our attempt to gather skills information from translators.

If we gather information via the Open.Michigan website via form, it may be difficult to link that information with the participants on Amara, as the two have separate accounts. Ideally, users of both systems will enter their name and/or same email address, but the decoupling of these sites might pose a problem if not. Alternatively, we can ask that users enter their proficiencies under their Amara profile, but this is an entirely optional step and one we cannot enforce but only recommend.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we believe that if Open.Michigan wishes to scale up their efforts, they should consider switching from their currently primarily manual system to one that is more automated. We believe that switching to Amara will reduce the time spent and the number of steps required to get translators started and to review the translations themselves. The current signup process does not give the users much information about the videos besides a name; we believe creating a hub for the project with the videos embedded as our prototype demonstrates will create a more useful and enjoyable browsing process, which will encourage more volunteers to join the project. We believe the project’s successes so far are not the end of Open.Michigan’s video translation project, and hope that they continue to enjoy participation from people around the world as time goes forward and the project expands.

22

References

1.

Soegaard, M. (2010). Gestalt principles of form perception. Retrieved April 28, 2013 from http://facweb.cs.depaul.edu/sgrais/gestalt_principles.htm

2.

Smartling. (2013). Say Hello to the Global Web. Retrieved April 28, 2013 from http://www.smartling.com/globalweb

3.

W3Techs. (2013). Usage of content languages for websites. Retrieved April 28, 2013 from http://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/content_language/all

23