Institutional impacts of voluntary mergers of municipalities

advertisement

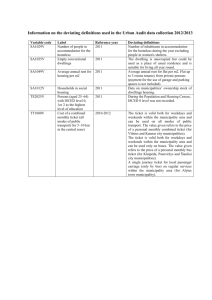

Voluntary amalgamations of municipalities: process and outcomes. Georg Sootla, Sulev Lääne, Kersten Kattai Tallinn University 1. Amalgamations and agenda for local government reforms The extension of welfare state as well as its crisis in 1980s (Brans 1992, Kjellberg,Dente 1989, Wolmann 2003 in Kersting&Vetter) fuelled the needs in substantial reforms of local governance. One of the directions of reforms was local government amalgamations. Amalgamation reforms have had a very different aims, mechanisms of implementation and outcomes. These reforms are to some extent analyzed in country studies (Schaap 2007; Vojnovich 2000) Christoffersen 2005), but to lesser extent in comparative perspective (Aalbu 2008, Dollery et.al. 2008, De Ceunic (2007),). Reforms are very often analysed at the level of reform rhetoric and intentions, which are poor guidelines for causal analysis of actual processes. Of course the reform strategy or statement would be important source and variable of reform outcomes, but amalgamation reforms frequently have different hidden agenda, among them agenda for improving the political power basis of leading reformers i.e. electoral success. Thus reform process and organisation would be the important dimension in analysing and predicting the outcomes and outputs of reforms. The elaboration of this new dimensions of analysis of amalgamation reforms would have special importance for several reasons. Firstly, amalgamation reforms have been mostly analyzed as merely (narrowly) administrative-territorial reorganisations and discussions abut these reforms focussed narrowly on the issues of size and efficiency, size and democracy (Dah.&Tufte Larsen 2002, Rose 2002). These debates have provided invaluable analytical framework for the understanding the size issue, but they can contribute only indirectly to the understanding the internal potential of amalgamations reforms. Moreover this narrow and instrumental stance does not enable to understand the possible links of amalgamation reforms with other local government reform initiatives (Caufield&Larsen 2002). The focus was somewhat extended by Krestin&Vetter 2003, but the amalgamations have rarely considered (Council of Europe 1995) as generic reform instrument for systemic solution of issues of local government roles as well as issues of intergovernmental relations. The second, the narrow approach can consider the tools – like cooperation or contracting as – not as alternatives to the amalgamations (Dollery et.al. 2005) but as premises or follow-up tools that may make amalgamations’ impacts more profound. The third, the outcomes of LG amalgamations have considered first of all from the perspectives of changes in effectiveness and democracy or functions/ competences acquired or lost. The institutional context and reform process has not been considered as a variable that might influence outcomes. Although impact of amalgamations on local politics has been studied (Kjaer 2009,), the analysis of amalgamations on internal structures of governance is almost absent. The fourth, debates over size has been based mostly on the positivist (public choice) methodology than counts only the agents’ perspective and micro-level of analysis. (Boyne 1991). This perspective is thus methodologically biased (Keating 1995), for it do not accept wider and institutional impacts. Maybe this was justified in case of traditional mergers in 1960-1970-s that were mostly instrumental responses to welfare state expansion. But it could not be accepted in the age, when variables such as global governance and increase in uncertainty and ambiguity in institutional environments have posed challenges to institutional patterns. The fifth, the amalgamation debate has remained, - because of neglect in institutional dimension -, in the framework of traditional understanding of intergovernmental relations as a set of carefully fixed and legally defined tiers on the one hand, and traditional perception of local autonomy either from libertarian or communitarian perspective. In CEE countries the intergtovernmental relations are perceived even from perspective of defensive democracy (autonomy) (Sootla et.al. 2001). Thus, current analysis of intergovernmental relations and practices of amalgamations reform must be based on the extended concept of subsidiarity and multilevel governance. This was understood by F. Kjellberg already at the beginning of 1993 (Kjellberg 1993) as the integrative approach to IGR and summarized in comparative perspective by his followers (Montin&Amna 2000). The most radical view in this issue was promoted by H. Baldersheim (2001: 209) who states: “Local government reform in European countries has been a pursuit of two himeras: the ideal size of municipalities and the ideal division of functions between levels of government. ..The precise municipal size and functional distribution are not at all important for effective governance. What is important , however, is the pattern of coordination across levels of government, or the mode of multi-level governance.” Thus from the perspective of multilevel governance the amalgamation as redesign of boundaries and concentration per se would not be useful and effective tool of redesign of institutional patterns of governing vertical. We expect that amalgamations are feasible as soon as they are producing certain institutional effects in order to introduce (or move towards) the patterns of multilevel governance. The impact of reform process and organisation of reform (type of reform) on outcomes would be especially important dimension of analysis in studying the role of amalgamation reforms. 2. Key issues of the process of amalgamation Amalgamation reforms are rather clearly located geographically: the boarder-line between those countries / regions which have chosen amalgamation as the tool of capacity building and those that are not is following almost exactly -- with some exceptions -- the along the protestant-catholic cultures (what is more important) in countries/ regions where autonomous/ dual pattern (Leemans 1970) of central-local relations were established. This is some sense paradoxical. Countries with more centralized / fused system of local government where the latter have been arm length of central (state) authorities and where possibilities to impose top down reforms are much higher have used amalgamation in exceptional cases, and put emphasize on the mechanisms of inter-municipality cooperation that dates back in France as far as 1890 (Council 1995: 143). Why? In Continental/ Napoleonic world the preservation of huge number of small communities can be explained by strong tradition and more conservative stance of local community members, i.e. the prevailing of traditional values of autonomy. (There are for instance three municipalities without any inhabitants in France in the areas of battle during I World War). In Anglo-American word the intensive amalgamations could be explained by majoritarian policymaking style and libertarian values that promote exit option among citizens and a very instrumental/ calculative values of local government (Wolmann 1995). In Nordic countries the local communities are strong and also very oriented on values of autonomy and self governances. But in these countries municipalities – although they were before amalgamations larger (in number of population) – rather easily agreed with the amalgamations initiated by the government and passed two waves of mergers after II WW. As a result in Nordic area the role of public servants of municipalities in the total number of public servants in the country was in Denmark 73%, Finland 74% (both before new wave of mergers) and in Sweden 58%, as compared with 20% in France, 14% in Italy, and 22% in Spain, but in Germany, where considerable mergers were in Northern lands in 1970, this proportion is 37% / . (Managing Across levels 1997:37). Why they agreed to replace the traditional community based municipality with larger and service based area-municipality? My hypothesis is that local authorities see and were able to negotiate in these countries not only changes of boundaries but also profound institutional changes, first of all the development of new power balance that would restrain general centralizing and globalizing trends in the modern world. So we can differentiate two dimensions for the analysis of amalgamation reforms. In the first dimension we evidence on the one hand instrumental aims and outcomes that could improve performance of local service delivery via the changes of boundaries. Very often these reforms reduce the immediate scope of municipal authorities through the contracting out services to private sector and even formation of “virtual government” in Australia (Dollery et.al. 2005) On the other hand we evidence comprehensive institutional reform along all governing vertical from intergovernmental relations to internal structures of municipality and to the citizens as beneficiaries. This kind of reforms we see in Denmark (2007), Latvia (2009). In Germany the logic of multilevel governance was introduced through the territorybased administration and vertical cooperation (Wolmann 2003). The variety of reforms in this dimension is not expressed in the different radicalism or intensity but in different types of outputs and outcomes. Often very fast and overhauling reforms can produce minor outcomes whereas gradual reforms of critical point (so called butterfly effect) can produce very deep institutional changes. In the second dimension we evidence on the one hand completely top down reforms and on the other hand completely bottom up reforms, whereas the majority of them hybrids that are closer to one or another end of continuum. The supplementary dimension that must be taken into account is politicisation of reform or vice versa, considering the aims of reform as purely technical-analytical task. Hence we can develop the typology that enables more structured analysis of various practices of reform process. Figure 1. Types of amalgamation reforms (hypothetical location) Top down Strategy for institutional changes Denmark 2007 Mix Finland (PARAS reform) Bottom up Strategy for instrumental changes Australia (Victoria) 1995, Canada (Ontario) Australia (Queensland), Canada (New Brunswick) Estonia This variety of amalgamation reforms is extensive and for detailed comparison in is necessary to have much profound empirical data collection and analytical work. In current study we focus on the one of type of amalgamation reforms – on completely voluntary amalgamations in the context when other possible elements of LG development (i.e. the cooperation of municipalities) will not play important role and the government or other actors do not play any mediating or coordinating role (except technical-legal consultations) in the actual reform process. This has been the case in Estonia from 1996 onwards. We have to define also results and outcomes that initiators of amalgamations have intended and that are possible to achieve. I would break these outputs into three general groups. The first class of outputs are instrumental improvements in performance and quality: economy (of scale, scope) and efficiency; synergy from increased critical mass due to increased scope of budget which can be analysed well quantitatively. The qualitiative improvements at the government are the increase of professionalism and specialisation etc. There could be also quantitative changes in democracy: increase or decrease in political participation; changes in the support etc. The second class of outputs and outcomes are changes in internal structure of municipality that would cause qualitiative changes in internal integration and supplementary balances between actors, changes in civil society organisations, changes of roles of councillors, council and government and their interrelations etc. These are structural changes that define the general capacity of municipality ( and its actors) in intergovernmental relations and channels of multi-level governance. Amalgamations may simply transfer previous practices of government and organisation of municipality to the new enlarged unit or foster some techniques of management, for instance extension of practices of contracting out. These changes can increase the effectiveness or quality of services but can simultaneously worsen outcomes in the other dimensions of public life because of changes in social environment and space: in transparency, accessibility and accountability, in social integration. Thus simple changes in structures and techniques are not obligatorily producing meso-level institutional changes, but may on the contrary foster some controversies that did not appear so clearly in the old (smaller) community, and new actors cannot respond adequately to the new challenges and controversies that are inherent to the new enlarged community. The main source of misunderstanding in size-effectiveness ( democracy) debate was the presumption that the new size must produce only favourable outputs and outcomes. Even the most beneficial change will produce also new contradictions and source of weakness. Those challenges may be transitional (conflicts of identities), but may be and are symptomatic for larger communities (many of them defined in size debates, first of all in democracy and government) and will need specific institutional responses. Moreover, lack of shifts at institutional dimension may restrain the realisation of strength of new community, for instance the increase of its strategic capacity via increase of strategic roles of councillors or enabling more variety of services. The third class of outputs and outcomes are changes in marco-level institutions. We cannot provide full picture of possible macro-level changes because this presumes special analysis, including the use of scenario analysis. Here we can identify some impacts on intergovernmental relations. The first, amalgamation may result in principal re-arrangement of the logic of tiers and their interrelations. Obviously the large units may take the considerable amount roles of former second tier like in Denmark and Latvia where the county level was abolished and the new level (and type) of authorities (similar to French regions) were established that enables better to fit with EU regional policy. (The latter is the special output of the reform.) . It is necessary to note that the second tier is usually performing rather marginal role in service delivery but it has a very important balancing role in traditional central-local relations. What would happen after the abolition of intermediate level in intergovernmental relations? To answer on that questions the practice of those countries where the second tier is basic level must be studied first of all. The second, the increase of the capacity and reduction of number of municipalities, and emergence of more equal from the viewpoint of capacity units enables obviously to develop the new power-balance between levels (including the balance in the formation of local-national elites). This increase the bargaining powers of local authorities and presumably also the agenda of negotiations. The third, the capacity of local authorities and strength of their associations may shift also agenda for development issues towards the issues that enable but also presume large regional/horizontal cooperation (Papadopoulus 2007). For instance, it may promote the participation of local authorities and actors in EU Baltic Sea Strategy which is focussing on issues that are primarily relevant to local authorities operation. This might make even more inter-governmental relations more confused: the powerful entrance of horizontal (global) cooperation networks may substantially change the logic of power vertical. 3. Framework of amalgamations in Estonia In Estonia since 1996 there have been 52 municipalities from the original total of 256 that have decided to form joint local administration. As a result there are 227 local government units in Estonia by 2010. After the Local Government Act in 1993, the Riigikogu adopted in 1995 the Act on Administrative Division of Estonian Territory (www 1 ), which provided rules and mechanisms for amalgamations. In 2004 the law on “Support of amalgamation of local government units” was adopted on 2004, (www 2) but amended in 2009. Amalgamations in Estonia are completely voluntary and depend on agreement of local councils (first of all of local leaders) to merge. The government provide only a very general framework of requirements – concerning some actions and formal documents – that should be presented to the Ministry of Interior. One among the municipalities, who intend to merge must made the announcement-invitation to the other councils to start the negotiation on amalgamation (that is defined as “changes in administrative territorial organizations”). Councils who accept this invitation will establish joint committee that must prepare amalgamation agreement. If some of municipalities decide before the conclusion of formal agreement about amalgamation not to merge the process will start from the beginning. The amalgamation agreement must contain several documents to ensure minimum consistency in the local life during and after mergers. Amalgamations have completed after the new council is elected at the regular elections and the new mayor is appointed. There is some transition period concerning the transfer of the validity of legal documents (as soon as new ones will be completed) but there is not designed any special transition period for the installation of new institutional structures. This is the process like the “building the ship at the sea”. 4. Methodology and data This study rely in the three empirical analysis, firstly, of the local government capacity and cooperation (CBC 2006). It was the study of different aspect of capacity of municipalities in Lääne ja Hiiu county with the aim to establish the cooperation potential and opportunities in this region. The second (ETF 2007) was the study of political profile and structure of actors in Estonian rural municipalities. The third was the analysis of four complex amalgamation of municipalities (MoI 2008) that were carried out in 2005 in Estonia. The first and third projects the embedded comparative case study method was used where at the analysis the replication techniques were applied (Yin 1994.). The survey polls were used in limited cases at these projects to establish only general trends in capacity/ cooperation and opinions of actors on limited aspects of amalgamations. The second was the survey poll, which enable us to develop understanding of political profile and structure of Estonian rural municipalities. This article is focussed on the generalisations of data collected during those projects and aimed in the development of general concept of voluntary amalgamations as well as general hypothesis about the impact of the process of amalgamations to the outcomes. Thus we must refrain from presenting details of results of these studies in this article, which will be provided in (Sootla et.al. 2010). As you may see in the table 1, where the data of size of our cases is presented, the main problem of Estonian rural municipalities is the very low density of populations, which makes larger amalgamations impossible because it may make distance between centre and sub-regions and villages too extensive. (In Hungary, Slovak and Czech Republic the average density of population is from 90 persons/ km2 in Hungary and 116 in Czech republic and the size on municipality from 30 km2 in Hungary to 13 km2 in Czech republic) MoI 2008 Table 1. Size of municipalities after amalgamations New municipality Türi Saarde Suure-Jaani Tapa Number of units merged Size km2 Number of habitants 4 3 4 3 600 707 746 263 11 256 5 016 6 200 9 115 Density of population (per/km2) 18,8 7,1 8,3 34,7 The extensive territory makes very urgent the need of internal decentralisation and development of complex management structure of the new municipality. 5. The process and organisation of voluntary amalgamations At all amalgamations those who will be merged have some autonomy to decide. The completely top down amalgamations have been exception like in Victorian (Australia) where even local councils were temporarily abolished and transition to the new unit was managed by appointed from the state commissioner. (Dollery et.al. 2008) The reverse is true also in case of bottom up amalgamation. For instance in Canada (Vojnovic 2000) the higher (state) authorities are intervening when completely voluntary negotiation have jammed because of irresponsible veto-play of some actors; or state authorities are mediating negotiations and give authoritative neutral consultations for participants (like in Finland) at difficult negotiations. In Estonia we see, however, a specific case when actors other that negotiating authorities do not have any role. This makes the process of amalgamation a very controversial enterprise as the process and from the output perspective. 5.1. The scope of changes Voluntary amalgamations are reforms at micro level and can only in some cases concern or influence governing process even in the region (in case of changes of boundaries of the region or boundary dispute with neighbors). So, voluntary amalgamations can not at the outset to aspire the changes in intergovernmental distribution of tasks/ resources or power potential to balance the central government. Moreover, new large municipalities are treated in similar vein with small ones in the distribution of resources or in assistance in financing service provision. For instance for the provision of regional public transport the government provide extensive grants to private providers. The new municipalities may be comparable with mini-regions (with territory ca. 900 km2) butt hey are not eligible for that grants because their transport is considered as intra-municipal. This inequality can be observed also in investment programs and also in case of provision of other central government grants. 5.2. Sustainability of changes The voluntary mergers are starting figuratively from nothing. There is no institutional trigger of mergers except the will and mood of local leaders. Actually, the problem is even more profound. In most cases of voluntary amalgamations we studies they were not the first attempts but there were several previous attempts of amalgamations that have failed (See also: Vojnovich 2000 ). In Canada sometimes the higher (county or state authority) is intervening forcefully if some municipality is continuing to veto the amalgamation process. But this is not in case of Estonia where government has no authority to intervene. Moreover, the previous experience very little influence the next trigger and attempt to merge; the experience of failure may even be an obstacle to next attempts of amalgamations. I.e the process is not cumulative and partners are at every new leap starting from the very beginning. Moreover, the voluntary amalgamations that have been started can be reversed at any point before the amalgamation agreement and other documents are approved by the government. This specific of the process is the main reason why voluntary amalgamations tend to be (a) conservative in initiating profound institutional changes during amalgamations and (b) politicised, that enables for every participant at negotiations irrespective of their actual bargaining potential to veto the process in order to request considerable advantages for their municipal area. 5. 3. Persistence of traditional value of defensive autonomy The very concept of voluntary amalgamation is deriving from traditional values of local autonomy which is understood primarily as the tool of protection of community from unwished interventions or even impacts from outside. This is and understanding of uniqueness of community and its self-sufficiency: the necessity of manage its own tasks. This is a rather strong sentiment that restrains also the possibilities of cooperation and further delegation of responsibilities inside the municipality. The defensive stance is characteristic not only for the perception of central-local relations but also of the relations between neighbor municipalities. Neighbors may organize joint events and their leaders may have good personal contacts. Authorities of town and surrounding municipality may even locate in the same building (as it was in two of our four cases) and to have joint private lunches. But, they are rather unfamiliar about what happens in neighbors’ politico-administrative “kitchen”, because this the realm of community’s “private” life. Because, as political-administrative units they are competitors for scarce resources in the framework of centralizing power vertical in Estonia. For this reason neighboring municipalities know very few about each other’s concrete practices of government and management, about true intentions of its leaders and background of their strategic calculations. They had rarely take joint actions to solve and manage similar problems. I.e. whereas in Nordic countries amalgamations have been at least to some extent the logical consequence of previous (sometimes compulsory) cooperation, the level of cooperation between neighbor municipalities in Estonia which uses voluntary amalgamations has been negligible. Moreover, previous practices of the use of services of larger towns by citizens of surrounding municipalities (schools, sports facilities etc.) have in 1990s caused conflicts over the conditions and rules of reimbursement. For this reason the absence of previous experience had not developed enough level of trust between local authorities and communities and perception of predictability of their behavior. The prevailing (conservative) expectation is that mergers are useful primarily for larger centers of the area – future centre of new municipality – and they as stronger actor would continue the self-interested behavior during and after the mergers. So the negotiations for the smaller partners must as much as possible to neutralized this possibility. The negotiations are starting for this reason even not from zero base. This conservative presumption is not weakening also because there is no institutional support in direct (from government) and indirect (common value space) sense. This causes the politicization of single and insufficient issues at the negotiations and the process of voluntary mergers can even reduce the level of trust and may fail despite decision agreement to start negotiations. So partners at negotiations could face the tremendously difficult task: to come to the agreements beneficial for all in situation of zero-sum game. I.e. voluntary amalgamations contain high risk not to achieve optimal outputs even they can come to agreement. 5.4. Specific vision of problems to be solved and perspectives to be achieved. The top down reforms are trying to carry out some qualitative changes and innovations in future, let them be a bit vague and normative. The main task of leadership is the mobilisation of actors to support these aims. The decisions about whether to merge and under what general preconditions to merge have been already made. Negotiations must find out ways how to do that in a way that is beneficial to all. The type of amalgamation reforms are targeted to the aim to repair of certain technical discords in government and community. /Alabu et.al. (2008)/. I.e. participants are not aimed to develop a kind of new system but to improve existing one. Voluntary bottom up amalgamations have largely the similar stance but with important specific. Differently from bottom-up technical reforms voluntary amalgamations do not rely on carefully prepared account about technical aspects of governance. Voluntary merges may rely – even if leaders would have some rational plans and reflective expectations -- primarily on some kind of “theories in use” about possible (positive as well as negative) consequences and gains from amalgamations, that have emerged at the level of practical conciousness. These theories in use defend the status quo and, what is even more confusing, they cannot be overrules by reflective arguments. Concerning past experience these theories-in use are very often fears about outcomes of future changes and idealisation of certain dimension of traditional community life. For instance, there is widespread conviction that increasing distance from authorities reduces the effectiveness of political representation; or that politicisation of government in large municipality may harm the harmony of personal relations that was appropriate to small community. In some cases, when the theories in use are based on trends that may re-emerge in larger community, its arguments may serve as point of departure for new strategies. One of such theory in use was the emergence of peripheries which play constructive role in the design of strategy of institution building in new municipality. Hence is originating also the conservative stance of amalgamation negotiations and agreements. The aim of agreements is to preserve as much as possible elements of former community life and to change as less as possible in order not to risk to loss even currently valued aspect of small community. Majority of amalgamation agreements contain special provision not to initiate changes in the structure and management of municipality until next elections (i.e. after five years) unless extreme need may emerge (i.e. too few children attend the school). In two from four of our cases the new elections were held in electoral districts which were formed on the basis of ole municipalities. Each district got certain proportion of seats in the new council. Thus the new council was formed not on the proportional basis but on territorial basis. The result of elections were biased in favour of small municipalities where there were only one local party which got 70-90% of votes whereas the partisan votes dispersed between different districts. The expectations (theories in use) about future are usually on the contrary too optimistic a la emergence of critical mass for investments or emergence of economy of scale. Those expectations are actually projections of current issues/ deficiencies into future without clear understanding how those advantages would be realized in concrete actions. 5.5. Politicisation of amalgamations agenda Politics is unavoidable dimension of any amalgamation. The issue is not even how much but what kind of politics is accompanying amalgamations. When reforms are initiated and agreed at the top the politics is about core concepts and core interests of parties. Thus the consensus over certain strategy is difficult to find but if it is founded then the coordinated action and targeted changes are rather possible. At the voluntary bottom-up amalgamations every partner is coming at the negotiation table with set of demands on quarantees of single issues to retain the status quo or to have equal benefits for the area they are representing. Area specific interests are prevailing frequently over the interests of the community as a whole. Local citizens are carefully watching to what extent their leaders are defending their local interests and local leaders know that this is the main criteria of support to him/he at the next elections into the new council. I.e. politics here is also based on single issues and particular interests. At the same time all leaders as initiators of negotiations feel themselves responsible for the continuing of negotiations and are very sensitive about its possible failure. For this reason it is rather difficult not to accept demands of partners, first of all, to continue investments into already planned sites and to distribute future investments equally between sub-areas of new municipality. The second most urgent issue is the level of remuneration of public sector employees. Usually the highest salaries are established in the new unit. The solution of both issues in manner that can suppress the potential conflict at negotiation may considerably increasing fiscal pressures to the new budget. At the same time we did not identify in our cases any attempts to count the exact increase of expenditures in the future budget. At those mergers in which the town centre dominates these pressures were least because the town authorities as the most interested actor did not escalated their demands and frequently made concessions to smaller remote areas (former municipalities). In those mergers where smaller areas (municipalities) coalesced and were dominant side at negotiations these pressures were rather severe mostly because the dominant theory in use was that in the new municipality the interests of the centre will prevail at the expense of surrounding areas. Thus negotiations was seen by them as the last chance to attract investments to their area. This strategy would also be result of pressures of public opinion in rural areas to their leaders, who would like to demonstrate – before elections – how much they are caring about interests of their area’s inhabitants. Especially forceful have been pressures from the local elites of municipalities surrounding the town, who have usually less interested in mergers. Citizens of those municipalities are mostly consumers of services that are provided (and managed) by the town authorities and reimbursed by authorities of surrounding municipality. The must not worry about organisational and other problems concerned with the provision of services, but can contest the conditions of reimbursement. For instance, from 400 children of surrounding municipality, who attended a school only 100 attended school of their own municipality. This trend of mobility is characteristic to the consuming majority of services. Citizens of surrounding municipality who needed administrative services can do that in town because its authorities are located in town. So, for inhabitants the amalgamation would not change much. But mergers would matter a lot for local elites, especially for officials. Leaders of surrounding municipalities had two clearly opposite strategies. One of them – usually backed by local business -- were pessimistic about future of their municipality and thus actively supported mergers. The other tried to organize joint position of rural areas vs. town authorities based on widespread conviction that rural areas are losers from mergers at least in long term perspective. One of most difficult transformation is the formation of new administration. Problem is not so much in need to reduce the number staff, but in relevance of professional knowledge and skills of former generalists-employees in the new context when they must hold positions that presume specialisation and professional knowledge. This problem can be solved by effective retraining of officials. Unfortunately the voluntary amalgamations cannot provide necessary time and resources for capacity building and re-recruitment of officials after substantial re-training. Municipalities have chosen for this reason the most conservative scenario to staff transfer: majority of appointments are prepared before mergers and new vacancies are filled by internal competition. So, actually the staff with outdated qualification or retiring-age persons or those who have found more challenging work will leave the office and other are transferred peacefully to the new administration where they acquire the new skills in office. It may take for staff a year or even more to adapt in the new roles. 5.6. Preparatory activities: needs and possibilities Every reform must have some transition period when old structures and practices must be abolished and replaced by new structures and practices. Substantial innovations inevitably cause disturbances in the system, but the everyday functioning of the organisation must be ensured and necessary services and outputs must provided. Amalgamations are more radical reforms because this is merger of very different organisations: with different cultures, management practices, with different suppliers and contractors. For this reason the merger cannot be rapid and forceful unification of this variety under the single and hierarchical management but as gradual integration of this variety into one. (MacKay 2004) There are at least three dimensions that must be harmonized as soon as possible. The first are contracts with suppliers and service providers of old municipalities that must be analysed and revised into one strategy of supply and contracting. Obviously contracts of old municipalities in similar areas may be made under very different conditions (prices, obligations, sanctions) and contracts that are not beneficial for authorities can be revealed and cancelled. The second, policies and regulations of municipalities in different areas might be not only different but contradictory, simply because rules of conduct and standards in towns may differ from rules and standards in countryside. One big issue is the management of real estate and assessment of its value. The other, more romantic example are the rules of holding pets that in town is obviously different than in countryside. If the latter can cause emotional problems in developing similar rules for different contexts, the joint management of real estate must be organized at the outset. Thus all policies must be at least in some dimension revised and re-designed before general strategy of innovations is adopted. The third, cultures, practices, and traditions of management, communication and finances even in rather similar and standardized organisations, like libraries, kindergartens, schools, are actually very different although they may act in the framework of similar rules. It is urgent not only to make sense of differences but – what is more difficulty – to find ways how to integrate this variety under the single management. I.e. old and new elites must have very clear picture about ways of transformation towards new structural configurations. This is relevant also for understanding new roles and professional requirements of new government institutions and employees. There are two important variables that could heavily restrain the preparation and implementation of these changes. The shortage of time. Amalgamations are organized as extraordinary local change in the framework of regular general elections and all the timing and logic of the amalgamations must conform to electoral process. According to the Law the amalgamation agreements must be concluded at least six month before new council is elected. Elections in Estonia is held in October, so majority of amalgamation agreements are concluded in April. From that point the actual preparations can be launched at least in dimensions that we defined above. But this is most busy time in rural areas and electoral campaign have already launched. Former partners must now ensure their re-elections. As soon as reorganisation commissions are chaired by local leaders they can prepare minimum formal requirements that enables to form the new municipality, i.e. the draft of the new statute. Although the law on amalgamations provides that (a) all obligations and contracts must be analysed and (b) draft new regulations must be prepared, this minimum has been done only in selected cases. So, the actual preparation can start only after amalgamations. Fear of new conflicts. The analysis of actual variations of management practices or the analysis of existing contracts (obligations) may be only superficial or even is absent because negotiating sides are not willing to have supplementary conflicts before mergers and elections. After the elections the new authorities are so heavily involved into everyday management issues and they have to accommodate or even learn their new roles. Therefore the analysis and harmonisation in these three dimensions is as a rule postponed to the future. Amalgamations that are initiated from the top take much longer time and usually they have clearly demarcated transition period. New elected authorities have year-two for the redesign of internal organisation and practices whereas old administration and councils can arrange everyday administration. Simultaneously two papallel councils may act. So these two dimensions are clearly separated to let to the new authorities the time and space for reorganisations. Unfortunately voluntary amalgamations cannot provide such a transition period for contextual as well as political reasons. This reduces substantially the immediate effects of amalgamations as well as forces to postpone the actual reorganisations to future. 5.7. After amalgamations After elections there is short transition period when the legality of old acts are transferred into new. Until the preparation of new contracts, new regulations, new laws and development plan (that is obligatory in Estonia) the old acts of former municipal council are in force. So does the municipality administration that continue to act until the new government and administration has not been appointed into office. But the latter period is very short (ca. 2 month). The first managerial problem after merges is the leadership quality. The scope, complexity and multiplicity of tasks have grown even in those new municipalities where the centre town dominates, first of all the urban and rural specific must be mixed. In the most difficult situation appeared to be those municipalities where the new leadership has formed on the basis of elites from small former municipalities. They have faced with completely new tasks and knowledge requirements in case of almost all issues. Besides, they may transform the old management style and old theories in use into the new situation try to institutionalize them. For this reason the main aim for following two years has been in our cases first of all to establish and manage current processes, and there was almost no time to focus on issues of strategic reorganizations (even if these were provided by the amalgamations agreements). So, three years after mergers there were very few new acts concerning general policies in the new municipality. The new authorities were able to establish control over the fiscal affairs and supply contracts, but this control has not been reached still the level of concrete organizations (for instance the inventory of assets according to new rules). 6. Analysis of outputs and outcomes The development of new administrative unit after voluntary amalgamation has far from being the process of rational design and implementation. The very process of voluntary amalgamations contain too many restraints that does not enable to make it rational and well planned strategy. But, we can even in this situation speak about some very important outputs. 6.1. Efficiency – effectiveness outputs Amalgamations in 2005 were carried out in the period when upsurge in economy and salaries started in Estonia. In the period 2004 – 2007 (four years) the expenditures in three municipalities we studied increased from 52 to 71 per cent whereas the average increase in all municipalities in Estonia was 56,8 per cent. (MoI 2007) So the context for reforms was in general very supportive and even exceptionally favorable. But even in this favorable context one municipality in our case was able to increase its spending only 10% because of large investments (and loans) that was made before mergers. In this municipality the political pressures to the fiscal basis - primarily caused by amalgamation negotiations -- were most intensive. Thus, in this municipality the possible restraints of voluntary amalgamations have been most severe, whereas in other ones the efficiency outputs were positive. The total costs of local administration increased in all new municipalities, but much less than total increase of expenditures. The proportion of costs of administration decreased in three cases (in one of them almost 40 per cent) but increased in abovementioned fourth municipality 13,7 per cent. In all municipalities the number of public servants in administration decreased up to 40%. The second important change was the shift in the proportions of other expenditures. In sectors which provided more standardized services that cannot be underfinanced (first of all education, libraries) even in small municipalities the costs per capita increased much less than in sectors/ areas which were underfinanced especially in former smaller communities (selected examples: road maintenance, culture and sport). The proportion of current education expenditures per capita in the budget dropped in all municipalities 8-10% and discharged recourses were re-distributed to sectors that were underfinanced. This is an indicator that the most obvious and important outcome of amalgamations is – in new democracies -- not the economy of overall resources but, firstly, the achievement of level of financing that ensures minimum quantity and quality, i.e. issue of equity; and, secondly, the reduction of costs in sectors were demand is too small for achieving optimal costs per unit. Fir instance, the costs per pupil at schools was in small rural schools up to three times higher that in towns, although the quality of teaching may have on the contrary – much lower (due to quality of teachers and use of composite classes. These costs cannot be avoided immediately. But it presumes profound redesign of school management system in new municipality. The next effect was increase of critical capacity of the development among larger new units, which investment capacity become three times higher (in absolute terms) than it was before mergers. So, our finding was (that confirmed also in the analysis of the evolution of staff) that there is the critical threshold of population size that enables to achieve qualitative shifts in capacity and positive outcomes. 6.2. Effects on local administration The main effect of mergers was the increase of professionalisation of staff through the specialization, considerable increase of proportion of staff with university education and decrease of staff with old-fashioned professional secondary education. In small communities majority of staff was multifunctional, i.e. the combine in actual work different task-assignments. Only two positions – mayor and accounting officer – were full time monofunctional employees. (Even CEO had in two municipalities supplementary tasks.) After mergers the proportion of monofunctional official reach 67-69% from the staff in larger units and 47% - in smaller units. Besides, the number of new tasks-assignments increased as much as twice in larger municipalities. Nevertheless these changes in specialization were not enough for the development of stable public service staff, for even large municipalities were not able to employ certain professionals due to the lack of them in the area (architects, lawyers, education managers etc.) So, the threshold of critical mass in building the administration is even higher than these amalgamations achieved. Our survey indicated several important directions of changes in the work of council and administration. These are: substantial increase of workload of councilor in council and in commission (that is indicated also by MacKay 2004), increased role of administration in assisting the preparing policy proposals and specialization of councilors on certain policy issues. To some extent there is more politics (i.e. conflicts) in the council and relations of councilors have become more formal. At the same time, majority do not agree that contacts with citizens have weakened Table 2. Changes in the work of council (councilors opinion) (N=39) Issue Certainly To some extent Not at all There is more politics in the council 34,2 26,3 39,5 More time needed for the work as councillor 51,3 35,9 12,8 Amount of work in the counsil has increased 51,3 28,2 20,5 I can focus on issues that is more interesting for me 23,1 64,1 12,8 Public servants assist better in the preparation of proposals for the council 35,1 51,4 13,5 Less contacts with citizens 10,3 35,9 53,8 Relations between councillors are more formal 5,3 50,0 44,7 Survey of public servants indicated that the work in the new positions presumes much professionalism and there has been improvement of work environment that enables more effective work. At the same time for large majority the level of bureaucratization has increased: there is more paperwork and less contacts with citizens, relations between public servants are more official, workload is more evenly distributed and contacts with mayor have lessened for majority of public servants. We get also confirmation about changed roles/ relations between council and administration. On the one hand, assistance of councilors by public servants has increased, but this does not mean that a kind of village life pattern (Peters 1996) have emerged. On the contrary: majority of officials emphasized weaker collaboration with councilors. Table X. Changes in the work of administration (public servants assessments) (N=44) Issue Certainly To some extent Not at all The work presumes higher professionalism 56,8 27,3 15,9 There is more paperwork, less contacts with persons 34,1 38,6 37,3 New work environment enables more effective performance 44,2 32,6 23,3 Relations between public servants are more official 25,0 47,7 27,3 Workload is more even and better planned 22,7 40,9 36,4 More cooperation with councillors 4,6 38,6 56,8 Less contacts with mayor 16,3 39,5 44,2 At the same time two thirds of citizens expect that administration is dealing with citizens problems more efficiently, but the same proportion expect that authorities are after merges more remote from citizens. Hence, we revealed some spontaneous, unplanned trends in the development of main governing institutions. We evidence more dynamic balance between main institutions and more effective role taking, whether it has positive (professionalism) or negative (bureaucratisation, weaker links with citizens) consequences. These strength might be increased and impacts of weakness might be decreased if changes had been intended and planned. But in general the voluntary amalgamations may achieve certain instrumental outputs even in the presence of considerable obstacles of their intentional achievement. 6.3. Changes in institutional structure of new municipality. The next set of outputs are change in patterns of actors of new municipal area and its institutions. There are three dimensions of those patterns: institutional, organisational and spatial. Profound structural changes can happen only in case when those are initiated simultaneously in all these three dimensions. We evidenced in the previous sub-chapter that spontaneous changes in council and executive and patterns of their interactions did not produced in mid-term perspective enough clear changes in institutional setting. At the same time we found rather clear changes in the territorial structure of those new municipalities where it was supported by the explicit strategy of its design. The most elaborated strategy was designed in largest municipality which has strong town centre and least extensive territory (Tapa). But some elements of new structure were introduced in all four cases. According to the law municipalities must establish service centres outside of municipal centres. When in other new municipalities all those centres were established at the old centres of municipalities then in Tapa municipality the new territorial sub-areas of municipality did not coincided with the boundaries of old municipalities but mirrored the future balance of different areas and community centres. Besides, at centers of those sub-areas the multifunctional community centres were developed instead of service points with limited functions. In three municipalities the community centre was not established in former surrounding municipality centre because it was formerly located in the town centre. In Tapa it was established also in surrounding municipal centre to ensure decentralisation of some activities from the town also to surrounding countryside. The second shift was the development of mechanisms of representation. Traditionally most of new municipalities established a kind of forum of representatives of villages and NGOs to receive feedback from them and to assist them in developing plan of coordinated activities. This was however too top down device in triggering civil society initiatives outside of the new municipality centre. Two municipalities developed representation (i.e. input) channels of sub-areas at the council’s commissions and at the executive. Representatives of sub-areas formed the mayor’s cabinet. In those municipalities we observe also the rise of new active centres in sub- areas and emergence of integrative trends between municipality centre and sub-areas. Combination of territorial and institutional changes provides in some cases much profound and lasting effect. Amalgamations in Estonia give impetus to the considerable re-design of territorial structure. At the same time the necessity to initiate qualitative changes in organisational structures were not even discussed seriously in the agenda. The underestimation of necessity of changes in internal organisation of authority and service provision in the new municipality – except the development new territorial structure -- is caused not only the absence of time and willingness not to trigger unnecessary conflicts during amalgamation negotiation. It is caused large extent also by the presence of different theories in use. In the perspective of territorial structures there was a very strong understanding of the necessity of structural redesign and also practical ways how to avoid the emergence of internal peripheries. The traditional perception and understanding of local autonomy presumes often that the application of subsidiarity principle ends at the doors of local administration. I.e. local authorities must have substantial autonomy vs. central authorities but local actors and all public activities must be tightly integrated as much as possible under the single roof mayors office. (This is the focus of our other paper at NPSPA conference.) In the development plans adopted in 2006 we found various new initiatives of improvement of services of various organisations, but we found little intentions to redesign the organisational structure of the new municipality in general as well as in certain sectors. There have been only minor changes in reorganisation of management of area-services, all of them were aimed to centralize under one roof of organisations spread in different sub-areas of the new municipality, first of all libraries. So we evidenced rather controversial changes in the second class of outputs and outcomes which are cause first of all by the specific of voluntary amalgamations but also by the strong persistence of theories in use which are reinforced by this specific. Changes at the second level presumes much stronger reflective and mediating mechanisms of the reforms to overcome the restraints set by voluntary amalgamations and to provide stronger strategic component in the planning of future changes. 6.4. Outcomes at macro-level Voluntary amalgamations can cause a very small changes in the system of intergovernmental relations, which remains the same even after numerous amalgamations. They cannot receive new assignments from the state level and basic principles of budget formation remain untouched. In general the position of new municipalities in intergovernmental vertical may even worsen. Although they formed the municipality in large area (or local region), i.e. de facto the second level they are still considered as single small units and they are not eligible of many benefits that is available for local regional units. As soon as they become more capable the general (block) grants from central government for them reduces. So, voluntary amalgamations cannot achieve outputs and outcomes that make major rational of amalgamations as complex and time and resource consuming enterprise. I.e. costs and risks of amalgamations may rather often be higher that possible benefits in case of very successful merger profess. For this reason potential participants of amalgamations are very careful in initiating the mergers. This makes the amalgamations for central government to large extent like facade reforms which function is to justify their inactions in initiating profound local government reforms. In sum We evidence that voluntary amalgamations are a very complicated process with many variables that influence and restrain the outcomes of that enterprise. The most important restraining variables are, firstly, the lack of general framework for changes with clear conception and guarantees for new and qualitatively different municipal units. This reduces the effect of outcomes even in case those effects are actually prepared and they may in other conditions to give effects. The second, this amalgamations are to large extent the zero sum game that may develop even into negative sum game, with all possible suboptimal outcomes that are deriving form such games. It is therefore even surprising how important outputs and outcomes those amalgamations have achieved. I.e. amalgamations may produce rather important changes and in case on favourable factors -- like reflectivity, systemic character of changes, active mediation of negotiations – those outcomes may be impressive. Thus voluntary amalgamations that is based actually on the theory in use of traditional autonomy can not meet challenges that changes in institutional contexts have produced for local authorities, i.e. when only responses towards the multilevel governance are feasible. References 1. Aalbu, H., Böhme, K., Uhlin, Å. (2008) Administrative reform – Arguments and values. Nordic Research Programme 2005-2008, research report, Stockholm Nordregio; 2. Erik Amnå and Stig Montin (Ed) Towards a new concept of local selfgovernment? : recent local government legislation in comparative perspective. Bergen : Fagbokforlaget, 2000 3. Baldersheim, H., Ståhlberg, K. (2002) From Guided Democracy to MultiLevel Governance: Trends in Central-Local Relations in the Nordic Countries. Local Government Studies, Vol. 28, Issue 3,74-90 4. Baldersheim H. Subsidiarity at Work: Modes of Multi-Level Governance in European Countries. - In: Caufiled&Larsen 5. Bouckaert et.al. Trajectories for modernizing local governance. Public Management Review, vol. 4 issues 3, 2002 6. Boyne, G. (1992) Local government structure and performance. Lessons from America? Public Administration. Vol. 70, Autumn, 333 – 357 7. Brans, M. (1992) Theories of local government organization: an empirical evaluation. Public Administration, Vol 70, 429-451. 8. CBC 2006 Capacity of local authorities in Lääne and Hiiu county and the development of their cooperation strategy. CBC PHARE project 9. De Ceunick K. Municipal Amalgamations in Belgium and the Netherlands: the principal cimilarities and differences. - Paper presented at the EGPA Annual Conference, Madrid 19-22 September, 2007 10. Council of Europe (1995) The size of municipalities, efficiency and citizen participation. Local and regional authorities in Europe No 56. Council of Europe Press. 11. J. Caufiled & H. Larsen Local Government at the Millenium.Opladen 2002 12. Christoffersen H. Local Government Structural Reform and the Efficiency Potential in Larger Organisational Units. Paper Presented for the Interrreg IIINO ASAP project “Efficient administrative structures as a prerequisite for successful social and economic development in rural areas in demographic transition”. https://www.kreislwl.de/Der%20Landkreis/partnerschaftenUndProjekte/asap/Seiten/default. aspx 13. Dahl, R.A., Tufte, E.R. (1973) Size and Democracy. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA. 14. Dente H., Kjellberg F. (Ed.) Dynamic of Institutional Change. London: SAGE, 1988 15. Dollery B., Garcea J., LeSage E. Local Government Reform. Comparative Analysis of Advanced Algno-American Coutries. Edward Elgar 2008 16. Dollery, B., Johnson, A. (2005) Enhancing Efficiency in Australian Local Government- An Evaluation of Alternative Models of Municipal Governance. Urban Policy and Research, Vol. 23, No. 1, 73–85 17. ETF 2007 Local authorities and public participation. The study of Estonian experience. Research grant delivered by Estonian Science foundation, 2006- 2007 18. M. Herweijer, R. Fraanje Do Institutions matter? Effects of an imposed merger of municipalities in comparison to a locally initiated merger of municipalities.- Paper presented to the ECPR General conferences, September 10-12. 2009, Potsdam, Germany 19. Keating M. Size, Efficiency and Democracy: Consolidation, Fragmentation ans Public Chioce. – In: Judge d. et al. Ed. Theories of Urban Politics, SAGE 1994, 117-134) 20. Kersting N., Vetter A. Reforming Local Government in Europe. Leske 2003 21. Kjaer U., Hjelmar U,, Olsen A. (2009) Municipal Amalgamations and the Democratic Functioning of Local Councils: The Danish 2007 Structural Reform as Case. - Paper to be presented at the EGPA conference. Workshop IV on Local Governance and democracy, Saint Julian’s, Malta 2.-5. September 2009. 22. Kjellberg F. (1993) Between autonomy and intergation. Paper presented to the International Seminar Process of Institutionalisation at Local Level, Oslo June 1993 23. Larsen, C.A. (2002) Municipal Size and Democracy: a Critical Analysis of the Argument of Proximity Based on the Case of Denmark. Scandinavian Political Studies. Vol. 24, No. 4, 317-332 24. Leemans, A. (1970) Changing Patterns of Local Government. IUAL 25. Lowndes, V., Sullivan, H. (2008) How Low Can You Go? Rationales and Challenges for Neighborhood Governance. Public Administration, Vol 86, No 1, 53-74. 26. Managing Across levels of government. OECD 1997:37). 27. MoI 2008 Local government amalgamations in Estonia: process and outcomes. Grant delivered by Estonian Ministry of Interior 28. Ruth B. McKay (2004) Reforming municipal services after amalgamation. The challenge of efficiency. - The International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 17 No. 1, 2004, pp. 24-47 29. Papadopoulus J. (2007) Problems of Democratic Accountability in Network and Multilevel Governance. – Eyropean Law Journal vol. 13 N 4 30. Peters, B. G., Pierre, J. (2001) Developments in intergovernmental relations: towards multi-level governance. Policy & Politics, Vol 29, No 2, 131-135 31. Rose, L.E. (2002) Municipal size and local non-electoral participation: findings from Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, Vol 20, 829-851 32. Schaap, L. (2007) Problems in Local governance and governmental scale. Paper presented at the EGPA Annual Conference, Madrid 19-22 September, 2007 33. Sootla, G. Kattai K, Viks A. Kohalike Omavalitsuste Ühinemised: Teooria ja Analüüs. Tln. 2010 (forthcoming) 34. Vanberg V. Subsidiarity, Responsive government and Individual Liberty. In: B. Steuenberg& F. Van Vught Political Institutions and Public Policy.Kluwer, 1997 35. Vojnovic, I. (2000) Transitional impacts of municipal consolidations. Journal of Urban Affairs. Vol. 22, No. 4, 385–417 36. Wolmann H. (1998) Local government institutions and democratic governance. In: Judge et.al. (Ed.) Theories of Urban Politics, SAGE, pp. 135-159 37. Wollmann H. (2003) German Local Government under the Double Impact of Democratic and Administrative reform.- In: Kersting N., Vetter A 38. Robert K. Yin (1994) Case study research : design and methods Sage Publications www 1 https://www.riigiteataja.ee/ert/act.jsp?id=778809 www 2 (https://www.riigiteataja.ee/ert/act.jsp?id=1011706)