Classical Tradition, Adolf Loos and late 20th century art

1

Classical Tradition, Adolf Loos and late 20th century art

Jan Bažant

1.

The first scientifically-precise reconstruction of a Classical building from Greek antiquity

- the Villa Kérylos - was built at a time when it looked as if classical morphology had breathed its last and the very era of speaking architecture was over

1

. By the beginning of the 20th century the first purely functional buildings were being created, their silent facades and totally undecorated interiors in stark contrast to the candidness with which the Villa Kérylos spoke of its builder. It demonstrated his social, political and academic ambitions and his attitude to the wave of anti-Semitism which was then dividing French society

2 , as the villa’s architecture recalled the

Delos of the second century BC, a cosmopolitan island peopled not only by Greeks and Romans but also by traders from Palestine and Egypt; it was also the site of the oldest synagogue outside

Palestine. The builder and his architect each had his own personal and professional reasons for creating such a striking celebration of Classical Greece on the Côte d’Azur 3

,which explains the outspokenness and authenticity of their return to Classical traditions, although there was nothing eccentrically escapist per se in that return. Even in the ostentatious anti-classicism of the 20th century architects will often stick closely to the Classical tradition, but rather like their predecessors in the second half of the nineteenth century they fail to realise that the connection

1 Beaulieu-sur-Mer, 1902-1908. Cf. J.-C. Delorme, Architects’

Dream Houses, New York 1994, 85-95; R. Vian des Rives, “La villa grecque Kerylos. Un hymne a la sagesse”, L’objet d’art 316,

1997, 62.

2 The idea came from Theodore Reinach, professor of classical studies at the College de France (1860-1928), who was also a historian of the Hellenistic period whence came the model for his villa (concerning Reinach cf. A. Rouveret in: A. Reinach, La peinture ancienne, Paris 1985, vi-xi).

3 The construction of the villa was entrusted to Emmanuel

Pontremoli (1865-1965). In 1890 he had won the prestigious Grand

Prix de Rome and had devoted himself to Hellenistic Greek architecture as a member of the French archaeological expeditions at Pergamon and Didymos (cf. Pontremoli, E.-

Haussoullier, B., Didymes, fouilles de 1895 et 1896, Paris,

1904); he subsequently became the leading representative of the conservative tendency at the Parisian Ecole des Beaux Arts (cf.

A. Bruccleri ”L’Ecole des Beaux Arts de Paris saisie par la modernité” in: J.-L. Cohen, ed., Années 30. Architecture et les arts de l’espace entre industrie et nostalgie, Paris 1997).

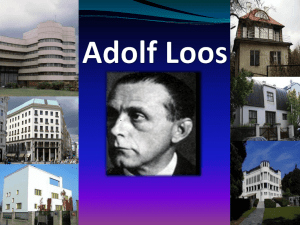

2 with ancient Greece and Rome is the guarantee of future development. The first to draw attention to that paradox was Adolf Loos (1870-1933). His taste was formed in the 80s and early 90s of the last century when Ibel’s Budapest Opera House, Semper’s Vienna Burgtheater, Zítek’s

Prague National Theatre and Rudolfinum and Wallot’s Berlin Reichstag were coming into being amid incessant lamentation about the absence of a contemporary style. Those buildings draw inspiration from ancient Roman architecture in a manner unprecedented in previous eras. While making direct reference to original monuments of ancient Rome and renaissance Italy they are inspired just as powerfully by buildings from the 18th and early 19th centuries while at the same time solving the problems of modern representative buildings

4

.

Loos’ first villa, the Villa Karma 5

, was built in the same period as the Villa Kerylos. The novelty of its design outraged the local inhabitants to such an extent that the architect received a summons from the police and the customer eventually cancelled the contract. What caused the greatest offence was the provocatively bare facade. The vision of a totally smooth wall was already in the air at the time and a whole number of architects were tending in that direction, but where Loos differed from them was in his determination not to make a revolutionary change. His experience of functional buildings that eschew all decoration, which he had acquired during a visit to the United States, emboldened him to return in his work to the traditions of

4 A.Loos, “Architektur” (1910) in: Sämtliche Schriften, Wien

1962, 302-318 (p. 310: “Die zweite hälfte des neunzehnten jahrhunderts war erfüllt von dem ruf der kulturlosen: wir haben keinen baustil! Wie falsch, wie unrichtig! Gerade diese zeit hatte einen stärker von jeder früheren periode unterscheidbaren stil als je eine zufor, es war ein wechsel der in der kulturgeschichte ohne beispiel dasteht,” p. 318: “Seitdem die menschheit die größe des klassischen altertum emfindet, verbindet die großen baumeister ein gemeinsame gedanke. Sie denken: so wie ich baue, hatten die alten römer auch gebaut. Wir wissen, daß sie unrecht haben. Zeit, ort, zwecke und klima, das milieu machen ihnen strich durch diese rechnung. Aber jedesmal wenn sich die baukunst immer wieder durch die kleinen, durch die ornamentiker, von ihrem großen vorbilde entfernt, ist der große baukünstler, der sie wieder zur antike zurückführt. Fischer von

Erlach im süden, Schlüter im norden waren mit recht die großen meister des achtzehnten jahrhunderts. Und an der schwelle des neunzehnten stand Schinkel. Wir haben ihm vergessen. Möge das licht dieser überragenden gestalt auf unsere kommende baukünstlerische generation fallen.”). Cf. M. Schwarzer, German

Architectural Theory and the Search for Modern Identity, New

York, Cambridge 1995.

5 At Montreux on the shore of Lake Geneva (1903-1904), cf. V.

Behalova, Adolf Loos: Villa Karma, Wien 1974.

3

Mediterranean architecture. It was in the Greek villages, where the Europe of his days sought out the relics of ancient Greece, that he found almost all the themes for his subsequent buildings - terracing that used local conditions, stairs that ended in landings, smooth white facades broken only by such doors and windows as were absolutely necessary, interiors with rooms extending over two floors and galleries in between

6

. As in Greek folk architecture, all one sees of the Villa

Karma from outside is a windowless wall. The facade is consistently symmetrical, with corner pavilions as in ancient Roman villas. An explicitly Classical quotation is the entrance with its representation of Doric columns and a simple architrave. In the entrance hall there is an abrupt change of tone, but we still remain in the Classical tradition - the central ground-plan, the checkered marble floor and the gilded mosaic on the ceiling of the entrance hall all evoke imperial Roman architecture. Also in sharp contrast with the incommunicativeness of the main facade are other internal areas of the house and all the garden facades which are linked as far as possible with the surrounding nature, while on the north-west side there is the suggestion of a

Classical peristyle with Doric columns. The supreme Classical quotation is to be found in the bathroom, where the client, a Viennese psychiatrist, wanted to evoke the mystery of the human body. Running up from a dark bath lined with black marble is a staircase bordered with Doric columns, reminiscent of the Propylon at the Acropolis in Athens. The aim, however, is not the daylight and a temple of virginal Athene, but a hermetically-closed bedroom ruled by Eros

7

.

Loos’ classicism is no passing phase as in the case of Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe at the beginning of their careers, but a permanent feature of his work

8

. The coffered ceiling of his

American Bar in Vienna of 1907 recalls the Classicist architecture of the traditional English club and by using mirrors to perform illusionist tricks he made the interior recall fantastic architecture in the style of 4th-century Pompeian paintings

9

. In 1910 Loos designed a department store for

Alexandria with gigantic Ionian pilasters topped by a pyramid-shaped peristyle. He returned to the Classical architectural language even after his modernistic villas of 1910-1913. The salon of

6 Loos visited Greece in 1902 and made a further trip in 1906 when he made a more thorough study of Greek traditional architecture. Cf. B. Rukschcio, R. Schabel, Adolf Loos, Leben und Werk, Wien und Salzburg 1982; F. Kurrent, “33 Wohnhäuser” in: B. Rukschcio, ed., Adolf Loos. Ausstellung veranstaltet von der Graphischen Sammlung Albertina, Wien 1989, 107-134, pp. 107-

113.

7 B. Gravagnuolo, Adolf Loos. Theory and Works, London 1995, 112.

8 F. Kurrent,“33 Wohnhäuser” in: B. Rukschcio, ed., Adolf Loos.

Ausstellung veranstaltet von der Graphischen Sammlung Albertina,

Wien 1989, 107-134.

9 Cf. http://archpropplan.auckland.ac.nz/virtualtour/karntner_bar/.

4 the Villa Strasser (1918-1919) is dominated by a marble Classical pillar that separates the music salon from the auditorium while also defining its symbolic function. In 1919, he and his student

Paul Engelmann designed the Villa Konstandt for the city of Olomouc. The plans indicate a loggia with columns in front of the entrance on the garden side and alongside the front door a direct quotation from Classical Greek architecture in the form of a variation on the Erechtheum at the Parthenon in Athens. Further designs along those lines are the villas Bronner (1921),

Stross (1922) a Simon (1924). Other projects that do not follow the modernist intellectual and architectural trend are the memorial for the Emperor Franz Josef of 1917, and to a certain extent the plans for the Modena-Gründe social centre in Vienna (1922) and the administrative building for the Boulevard des Italiens in Paris (1925)

10

.

2.

Loos’ plan for reintegrating the heritage of ancient Greece and Rome into modern life was the logical outcome of the revolutionary changes in the concept of architecture that occurred in Central Europe in the 1880s and 1890s

11 . Crucial to Loos’ development was the rehabilitation

10 Evidence of Loos’ conservative political outlook is provided, among others, by his display of patriotic enthusiasm over

Austria-Hungary’s entry into the World War. Cf., for instance,

K. Kraus, Briefe an Sidonie Nádherný von Borutín, München 1974,

Bd. I, 90: (18th November 1914) “Loos verrät in gesprächen einer furor teutonicus. Das ist dann eine Verständigung noch schwieriger als sonst. Es gibt Dinge, über die man nicht reden kann.” Cf. B. Ruckschcio, R.L. Schachel, Adolf Loos. Leben und

Werk, Salzburg 1982, 199, 208.

11 Cf. W. Herrmann, ed., In What Style Should we Build? The

German Debate on Architectural Syle, Santa Monica 1991; M.

Olin, Forms of Representation in Alois Riegl's Theory of Art,

University Park, Pa. 1992; M. Iverson, Alois Riegl: Art History and Theory, Cambridge, Mass. 1993; H. F. Mallgrave, ed., Otto

Wagner: Reflections on the Raiment of Modernity, Santa Monica

1993; H. -W. Kruft, The History of Architectural Theory from

Vitruvius to the Present, New York 1993; K. Frampton, Studies in

Tectonic Culture. The Poetics of Construction in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Cambridge, Mass. 1995; M. Schwarzer,

German Architectural Theory and the Search for Modern Identity,

Cambridge 1995; H. F. Mallgrave , E. Ikonomou, eds., Empathy,

Form and Space. Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873-1893, Santa

Monica 1993; H. F. Mallgrave, Gottfried Semper. Architect of the Nineteenth Century, New Haven, Conn. 1996; H. P. Berlage,

Thoughts on Architecture. Ed. I. B. Whyte, Santa Monica 1996;

J. Duncan Berry, The Transformation of Nostalgia. European

5 of baroque architecture and the return of fantasy to classical-style design. Otto Rieth, “the

Nietzsche of architectonic graphics”, had published his celebrated “Skizzen” inspired by Piranesi in the mid-1890s

12

. No less significant was the opposite trend: the “Architectural Realism” of

Albert Hofmann, Otto Wagner, Cornelius Gurlitt, August Thiersch, Heinrich von Ferstel, Josef

Bayer, Hans Auer, Richard Streiter and others which introduced new materials and techniques into traditional architecture and vigorously strove for its moral renewal. Loos became a fervent supporter of that approach during his stay in the United States in the period 1893-1896 when he was thrilled by the perfect functionality of American “things” 13 . “The Greek vases are beautiful in the same way as a machine is beautiful, as a bicycle is beautiful”, he wrote in 1894 14

. What made Classical architecture such an intense challenge for Loos was his contact with a civilisation which not only asserted resolutely its Classical heritage but was also capable of producing

“things” and buildings that were beautiful because of their perfect utility. As a result of his experience, however, Loos was one of the first Europeans to realise the negative implications of technical progress. Unlike his peers who tried to face up to the 20th century with social utopias,

Loos accepted the all-embracing uncertainty, alienation and anonymity of city life as an unfortunate but inevitable phenomenon

15

. According to Loos the human dwelling should react to rapid changes by consistently eliminating them - its task is not to create a new man but to preserve what we have inherited from our forebears. Loos’ villas were intended to isolate their inhabitants from the 20th century, as their severe and unwelcoming exteriors indicated. Their interiors were intended to serve the same function, but the manner in which they confronted the outside world was quite different - they created a parallel, self-enclosed world in which monumentality and luxury alternate with cosiness. In Loos’ view the architect’s role is to demarcate appropriate space for human moods and feelings, which is why in his interiors some space is intended to excite and to stimulate the imagination while other space is supposed to

Architectural Theory of the 1880s (in print cf. http://www.capecod.net/textiles/Prospectus.html).

12 R. Dollinger, "Otto Rieth, Architekt, Maler und Bildhauer,"

Architektonische Rundschau XXVIII (1912): pp. 13-16 + pls. 47-

62.

13 R.L.Schachel, “Adolf Loos, Amerika und die Antike”, Alte und moderne Kunst, 113, 1970 = “Adolf Loos, l’Amerique et l’antiquité” in: F. Fanuele, P. Verhoeven, eds., Adolf Loos

1870-1933, Bruxelles 1983, 33-38.

14 A. Loos, „Glas und ton“ (1898) in: Sämtliche Schriften, Wien

1962, 55-61.

15 Cf. Cacciari, M., Großstadt, Baukunst, Nihilismus, Klagenfurt

1995; B. Colomina, Privacy and Publicity. Modern Architecture as

Mass Media, Cambridge, Mass. 1996.

6 encourage relaxation and ease the troubled senses

16

. The analogy with Classical rhetoric was not fortuitous. According to Loos, the architect must speak to people in an intelligible language and tell them things to which they are accustomed, but at the same times he must never use the same words over again - people must never have the impression of having heard exactly the same thing before

17

.

Loos always attacked on two fronts, he criticised not only slavish imitation, as already mentioned, but also the attempts to create a completely new architectural language, the elitist

Esperanto that the avant-garde artists had been trying to foist on the public since the beginning of the 20th century

18

. In the same way that is impossible to invent a language or change an entire vocabulary and syntax all in one go, it is also impossible to change all the rules of architecture overnight. For the language of architecture to remain intelligible it must go on developing and in each generation it must reflect anew on its own history. At the centre of Loos’ innovatory approach was the spatial plan, the “Raumplan”. “The great revolution in architecture is the

16 A.Loos, „Architektur“ (1910) in: Sämtliche Schriften, Wien

1962, 302-318 (p.317: “Die Aufgabe des architekten ist es daher, diese stimmungen zu präzisieren. Das zimmer muß gemütlich, das haus wohnlich aussehen”).

17 A.Loos, „Architektur“ (1910) in: Sämtliche Schriften, Wien

1962, 302-318 (p. 317: „Die technik unseres denkens und fühlens haben wir von den römer übernommen.“). Concerning the relations between Loos and Wittgenstein see D. Barnow, „Loos, Kraus,

Wittgenstein, and the Problem of Authenticity“ in: Turn of the

Century. German Literature and Art, 1890-1915, H.H.Schulte,

A.A.Lee, eds., Bonn 1981, 249-273; C.St.J.Wilson, „The Play and the Use of Play: an Interpretation of Wittgenstein’s Comments on

Architecture“, Architectural Review 180, 1986, 15-18; K. Bering,

“Ästhetische Rätsel” : über Ludwig Wittgenstein“ in: Kunst und

Ästhetik, W. Scheel ed. (Arcus 1), 1997, 81-93.

18 A. Loos “Ornament und erziehung” (1924) in: Sämtliche

Schriften 1, Wien 1962, 391-398 (p. 396: “Unsere erziehung beruht auf dem klassischen bildung. Ein architekt ist ein mauerer, der latein gelernt hat. Die modernen architekten sheinen aber mehr esperantisten zu sein. Der zeichenunterricht hat vom klassischen ornament auszugehen. Der klassische unterricht hat trotz verschiedenheit der sprachen und grenzen die gemeinsamkeit der abendländischen kultur geschaffen. Ihn aufzugehen, hieße diese letzte gemeinsamkeit zerstören. Daher ist nicht nur das klassische ornament zu pflegen, sondern man beschäftige sich auch mit den säulenordnungen und profilierungen”).

7 solution of a plan in space” 19

. Whereas 18th and 19th century architecture used the ground-plan, material and decoration as it means of expression, Loos tried to achieve the same effect with space. Loos continued to concentrate on marble and mirrors as the way to express in his interiors what ornamentation had achieved in previous epochs. And as far as compositional types were concerned he returned again and again to the stepped pyramid, the cubic monolithic block and the corner cylinder.

Another major theme of Loos’ was the column, that dominates the facade of Loos’

Vienna house of 1909-1911

20

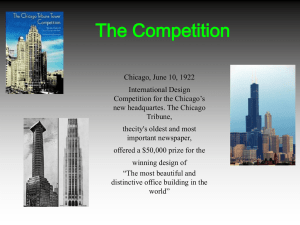

. That house on the Micheelerplatz was not simply a design, it was a manifesto and as such it caused outrage. The building plot allotted to Loos was directly opposite the most important historical monument in Vienna, the Hofburg, and Loos took up the challenge. He tried to draw inspiration from the architecture of Old Vienna while at the same time indicating that the city’s focal point had shifted for good from the royal court to the commercial/shopping centres. Loos’ house was intended as a bridge between the main Viennese palace and the most important shopping street in the Vienna of those days which still bore the name Kohlmarkt. In his design, tradition and the palace were represented by the building’s symmetrical classical composition and the monumental entrance conceived as a pronaos with four Tuscan columns. The 20th-century lifestyle and commerce were represented by the uniform facade inspired by American skyscrapers on which decoration was limited solely to the ground floor that was visible from street level. A further building-manifesto was to be Loos’ design for the Chicago Tribune skyscraper

21

. On 9th July 1922, the Chicago Tribune newspaper launched an architectural competition for the design of its new headquarters that was to be built on a prominent site in the centre of Chicago. The aim of the competition was worded most ambitiously: “to provide for the world’s greatest newspaper ... the world’s most beautiful office building”. The competition gained world-wide publicity thanks to the extremely generous prize offered for the successful entry. In the space of just a few months, hundreds of designs had already been received from 23 countries; the competition would seem to have been the most

19 A. Loos, “Josef Veillich” (1929) in: Trotzdem, A. Opel, ed.,

Wien 1982, 215: “Denn das ist die große revolution in der architektur: das lösen eines grundrisses im Raum”.

20 H. Czech, W. Mistelbauer, Das Looshaus, Wien 1977 (3rd ed.

1984); Das Looshaus : eine Chronik 1909 - 1989, Wien 1989; G.

Denti, Adolf Loos : la casa in Michaelerplatz, Firenze 1990.

21 Chicago Tribune Competition, Chicago 1922; P. A. Saliga, ed.,

The Sky’s the Limit. A Century of Chicago Skyscrapers, New York

1990, no. 32; J. Ryckwert, The Dancing Column. On Order in

Architecture, Cambridge, Mass. 1996, 19-24; http://www.architektur.uni-stuttgart.de:1200/projekte/loos.

8 important of its kind ever and in response to public interest, an exhibition of the competition entries went on tour the following year

22

. The winning entry, the gothic skyscraper of Howels and Hood that was built in 1925, immediately became the city’s symbol, but the entry that aroused the most discussion - and still does - was Adolf Loos’. His 21-storey skyscraper was conceived as a gigantic Doric column of polished black granite standing on a plinth and on either side of the entrance were pillars reminiscent of Loos’ house on Vienna’s Machaelplatz.

3.

When Loos was a young man, classically-inspired architecture was still a living tradition, never once broken until then. Ever since the fall of ancient Rome that tradition had been passed on from master craftsman to apprentice, from one generation to the next, simply being enlivened from time to time by study of preserved relics and Vitruvius’ guidelines. At the turn of the 20th century, however, the avant-garde, in the heat of its struggle with conservative taste, poured the baby out with the bath water, and after World War II there was a real danger that the classical architectural morphology, would become a dead language, like Latin or Greek. However, in the foreword to his design for the Chicago Tribune building Loos prophesied: “The great Greek

Doric column must be built. If not in Chicago, then in some other town. If not for the ‘Chicago

Tribune’ then for someone else. If not by me, then by some other architect” 23

. It is only in the last decades that his prophecy has been fulfilled, with architects turning back to Classical antiquity. 1980 saw the organisation of a touring exhibition entitled “Late entries to the Chicago

Tribune Tower Competition” and some of those designs overtly pay homage to Loos’ concept of a skyscraper in the form of a Classical column

24

. In the same year a demonstration in tribute to

Classicism took place at the Venice Biennale when twenty so far unknown architects exhibited a cardboard street of houses with Doric columns, arches and other Classical features. That “Strada

22 On the response in Czechoslovakia: J. Rössler, „Cyklus přednášek Klubu architektů v Praze“, Styl 5, 1924-1925, 176. Cf. also R. Švácha, „Adolf Loos a česká architektura“ Umění 31,

1983, 490-513.

23 The importance that Loos attached to the project is evident from a pamphlet devoted to the Chicago Tribune Tower entitled

“Should a Habitable Column be Allowed?”, that he published at his own expense in Nice in 1922.

24 S. Tigerman, Tribune Tower Competition and Late Entries, New

York 1980. During the 1980s skyscrapers inspired by the

Classical column were erected in New York (1983-87, Helmut Jahn at 425 Lexington Avenue; 1983-1987, Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo,

Morgan Bank) and Chicago (1987-1989, Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo,

Leo Burnett Building).

9

Novissima” was part of a project aptly entitled “Presence of the Past”. For that matter the return of the Classical column to architecture had already been foreseen in 1975 by Bernhard Schneider and Alessandro Carlini of the TU Berlin in their manifesto “The Return of the Column”. They also pointed out quite rightly that the exorcism of the column did not simply infringe a certain norm it actually undermined the idea of artistic norms. It represented nothing new: it was not the beginning of a new stage in artistic development, but a collapse, as cultural continuity without norms is impossible. Therefore the artistic works that accompany the manifesto make no attempt to return to the pre-collapse situation but instead they describe the transformation of architecture’s function whereby it ceases to be a model of the world and becomes mere amusement

25

.

In 1898 Loos wrote: “We are able to state that the great architect of the future will be a classicist - not a man who takes his lead from the work of his predecessors but one who goes back directly to classical antiquity” 26

. On the very threshold of modernism Loos understood what more and more architects are once more coming to realise, i.e. that classicism is not just the only modifiable, expandable and enduring compositional system it is also the only modifiable, expandable and enduring architectural form

27 . Loos’ prophecy can also apply to other genres, since in painting, sculpture and literature also, Classicism is proving to be the only art language with any future

28

.

25 Jahrbuch für Architektur 1981/1982, 174nn; H. Klotz, ed.,

Revision der Moderne. Postmoderne Architektur 1960-1980, München

1984, 250-251.

26 A. Loos: “Die alte und die neue Richtung in der Baukunst”

(1898) in: A. Loos: Die Potemkin’sche Stadt, Verschollene

Schriften 1897-1933, Adolf Opel, ed., Wien 1983, 66: “Wir können daher behaupten: Der zukünftige große Architekt wird ein

Classiker sein. Einer, der nicht an die Werke seiner Vorgänger, sondern direct an das classische Altertum anknüpft”.

27 R. A. Stern, Modern Classicism, London 1988 (= Moderner

Klassizismus. Entwicklung und Verbreitung der klassischen

Tradition von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart, Stuttgart

1990); M.-A. Laugier, Das Manifest des Klassizismus.

Studiopaperback. Zürich 1989; M. Greenhalgh, What is Classicism,

London 1990; New Classicism : Omnibus Volume, A. Papadakis, H.

Watson, eds., foreword by L. Krier, New York 1990; P. Mainardi,

The Persistence of Classicism (with contributions by Graham

Bader et al.), Williamstown, Mass. 1995.

28 Th. Beeby in: R. Miller „Thomas Beeby Talks to Ross Miller about Mies, Classicism, and his Recent Work“, Progressive

Architecture 71, 1990, 113-114; B. Groys, ”Body Trouble (exhibit on figurative representation at the 1995 Venice Biennale),”

10

Loos quite properly stressed that architecture is above all a craft: “The house must please everyone, unlike the work of art which does not need to please anyone. The work of art is brought into the world without there being any need for it. The house on the other hand satisfies the need ... The work of art is revolutionary, the house is conservative ... So the house should have nothing to do with art, and architecture should not be numbered among the arts? Exactly so.

Only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument. The rest, everything which serves an end, should be excluded from the realm of art”

29

. Thus in his critical detachment vis-a-vis the contemporary concept of art Loos took no more than the first step. It is not true that art must not please everyone or that it need not serve any purpose. Of course, every sculpture or picture must please everyone and serve a clearly defined function. By now it is clear that by declaring the autonomy of art, the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century played a key role in bringing about its decline and the consequent loss of its public. The assertion that a work of art is justified if it pleases just one person was the greatest mistake of the 20th century. It was a stupidity that led to intellectual shallowness and sloppy execution which purported to be authenticity. Buildings and events that we knew so well had to assume a comic and incomprehensible form in order to become a personal statement. Happily, however, the artists of the 1990s are abandoning the intrusive autobiographical tone and are starting to return to recognisable people, nature and real stories

30

. Likewise architects are again designing buildings for people, which, incidentally, explains the ever growing interest in Adolf Loos

31

.

Artforum 34, 1995, 40-42; H. De Billy, “Back from Abstraction

(Interview with Picasso Museum director Jean Clair)” World Press

Review 43, 1996, 40-1 (reprinted from L'Actualité, June 15,

1996).

29 A.Loos, “Architektur” (1910) in: Sämtliche Schriften, Wien

1962, 302-318.

30 F. Turner, “The Birth of Natural Classicism”, The Wilson

Quarterly, 1996, 20, 27-34.

31 It dates back roughly to 1960: H. Ammanhauser, “Quand le moulin s’endort, le meunier se réveille: la réception de Loos depuis des années cinquante” in: Critique de l’ornement: de

Vienne a la postmodernité, M.Collomb, G. Raulet, eds., Paris

1992, 133-142. Most recent literature includes: A. Opel, ed.,

Schriften von und über Adolf Loos, Wien 1988; L. Müntz, Adof

Loos: mit Verzeichnis der Werke und Schriften, Wien 1989; A.

Opel, ed., Alle Architekten sind Verbrecher: Adolf Loos und die

Folgen: eine Spurensicherung, Wien 1990; P. Tournikiotis, Adolf

Loos, Paris 1991 (= P. Tournikiotis, Adolf Loos, transl. from the French by M. McGoldrick, Princeton 1993); G. Denti, Adolf

Loos : architettura e citta, Firenze 1992; Adolf Loos : uno spirito sociale : gli studi sulle abitazioni operaie, G. Denti,

11

------------------------------------------

Published as: „Classical Tradition, Adolf Loos and Late 20th Century Art“, Studia Hercynia 3, 1999

(Akten der Tagung: Antike Tradition in der mitteleuropäischen Architektur der zweiten Hälfte des 19.

Jahrhunderts, Prague und Litomyšl, 10.-15. November 1999, Redaktion J. Bouzek, P. Líbal), 142-151.

S. Peirone, eds., Firenze 1993; K. Lustenberger, Adolf Loos.

Studiopaperback, Zürich 1994; E. B. Ottilinger, Adolf Loos.

Wohnkonzepte und Möbelentwürfe, Salzburg, Wien, Stuttgart 1994;

H. Loscher, “Genug der Originalgenies! Wiederholen wir uns unaufhörlich selbst,” Adolf Loos, das neuen und “das Andere”,

Daidalos 52, 1994, 76-85; Adolf Loos e il suo Angelo : "Das

Andere" e altri scritti, M. Cacciari ed., Milano 1994; K.

Lustenberger, Adolf Loos, Zürich 1994; L. VanDuzer, K. Kleinman, foreword by J. Hejduk, New York 1994; Adolf Loos, Über

Architektur : ausgewählte Schriften, ed. by A. Opel, Wien 1995;

F. Brunetti, Adolf Loos : frammenti di architettura viennese,

Firenze 1995; F. Roth, Adolf Loos und die Idee des Ökonomischen,

Wien 1995; W. Oechslin, Stilhülse und Kern. Otto Wagner, Adolf

Loos und der evolutionäre Weg zur modernen Architektur. Studien und Texte zur Geschichte der Architekturtheorie Bd.1., Zürich

1995; R. Schezen, J. Rosa, introduction by K. Frampton, Adolf

Loos : Architecture 1903-1932, New York 1995; R. Trevisiol,

Adolf Loos, Roma 1995; Adolf Loos : la cultura del progetto : atti del convegno tenuto presso il Centro congressi Cariplo di

Milano, 16-17 marzo 1995, a cura di G. Denti, e S. Peirone, Roma

1996; G. Spindler, Zur Affinität von Interieur und Mode : eine analysierende Gegenüberstellung theoretischer und praktischer

Konzepte von Adolf Loos und der Wiener Werkstätte, Salzburg,

Univ., Dipl.-Arb., 1996; Canto d'amore : klassizistische Moderne in Musik und bildender Kunst, 1914 - 1935, G. Boehm, U. Mosch eds., Bern 1996; Adolf Loos : opera completa, G. Denti, S.

Peirone, eds., Roma 1997; Adolf Loos, Ornament and Crime :

Selected Essays, ed. by A. Opel, translated by M. Mitchell,

Riverside, Calif. 1997; Adolf Loos, 33 Wohnhäuser, F. Kurrent, ed., Salzburg 1998; A. Moravánszky, Competing Visions :

Aesthetic Invention and Social Imagination in Central European

Architecture, 1867 - 1918, Cambridge, Mass. 1998; A. Lachmann,

Müssen vs. können, Ökonomie vs. Ornament : vergleichende Analyse der frühen Schriften von Adolf Loos und Arnold Schönberg, 1998; http://www.bk.tudelft.nl/d-arch/agram/loos; http://www.archinforum.de/arch/122.htm.