reformation struggle

advertisement

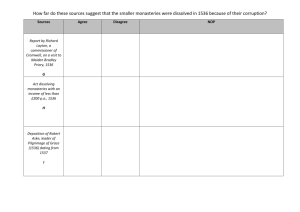

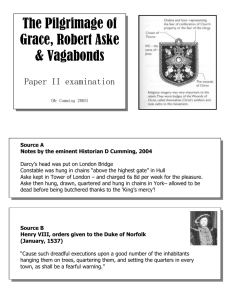

Lecture 8: Social Struggle During the Sixteenth Century I. Introductory Comments / logistics—Vera from the WRC here to talk to us about the facilities. Last time we discussed the dissolution of the monasteries and the socio-political ramifications of the crown taking over the lands. We looked at the readings and discussed the possibility that there may not have been a "reality" behind the stories about the monasteries, but there was enough popular recalcitrance to undermine them, that the Reformation politics could succeed fairly well. The RH story was a cultural embodiment of the way in which the monasteries were perceived—gluttonous, evil, conniving, etc. II. The Reformation as point of social contention—What we're going to do today is look at the English Reformation as site for social contention of all kinds and from all layers of society. This is an important aspect of the Reformation I think, because we need to see it emanating not solely from the confines of Kingly Proclamation, but resonated throughout the shires in manifestly different ways. All kinds of social issues were raised with the reformation, from the greed of the monks and the dissolution of the monasteries, to the enclosures of common lands, to the forced uniformity of action and prayer. England shows itself as decidedly heterogeneous in this regard, which shows Tudor England as fundamentally more diverse than previously imagined. III. Sir Thomas More to The Pilgrimage of Grace A. The Acts Written in Blood and the forced Acquiescence to Kingly Authority— The Act of Succession of 1534 and the consequent Act of Treason in December 1534 both enforced loyalty through bloodshed. That is, Henry would not take no for an answer (especially from More) nor would he tolerate seeming heretics. He was trying to have it both ways and in trying to enforce the legislation he executed ardent Roman Catholics and zealous Protestants. B. Thomas More's Position 1. Some biographical information (c.1477 – 1535) –trained in the law 2. His literary activities and his political stance—Thomas More was already acclaimed as a literary figure before his ascension to power as Lord Chancellor in 1529 (after the decline of Wolsey). Thomas More published Utopia in 1516, and the work is generally regarded as an important element in English literary humanism. Embedded in the work is the structure of rational government, of good government (refer to Lacey Sayegh lecture reformation struggle, page 2 Smith's discussion on pages 103-104). As a work of humanism, it focused on the business of men—that humanity was responsible for constructing not only viable, but humane governments. 3. His separation from the King—the role of Richard Rich, backstabber extraordinaire As I mentioned, More ascended to the position of Lord Chancellor—a secular position that heard pleadings in the courts, etc. that was formerly held by Cardinal Wolsey—in 1529. For a long time, he held the king's ear, but he resigned from that position in 1532, because he could not support Henry's justification for separating from the Church. He was ratted out by Sir Richard Riche who was a political and religious chameleon. He changed his shape to fit the religious proclivities C. The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the Pilgrimage of Grace 1. Social friction in the North—the pilgrimage of Grace was a spontaneous uprising against the dissolution of the monasteries in North England. Troubled by the extent and ferocity of Cromwell's push to take over the houses and redistribute the lands, many people throughout the country opted to take politics in their own hands. Shortly before the PG, there was an uprising in Lincolnshire which very quickly dissolved in about two weeks. A conservative region, but housing nearly 25% of the dissolved monasteries, Lincolnshire and York believed that Cromwell was doing the country a disservice and taking it on a road to destruction. The gentry who ran the affair were very quickly compelled to quash the uprising by the Duke of Suffolk. The King wrote a reply to the insurgents "rating them for their ignorant presumption and charging them to disperse" which they did (Williamson 145). 2. The role of Robert Aske—Robert Aske was a barrister in London from the area of York and led the revolt which broke out in late October 1536. He was also involved in the failed revolt in Lincolnshire. In all parts of the realm men's hearts much grudged with the suppression of abbeys, and the first fruits, by reason the same would be the destruction of the whole religion in England. And their especial great grudge is against the lord Cromwell Sayegh lecture reformation struggle, page 3 This statement very clearly elaborates his distaste for the direction of the Reformation. Aske and members of the gentry, such as Lord Darcy, took over York and amassed an army of over 30,000. They argued that they had the right to petition the king, and that they were not working to remove the king. While the pilgrimage ended in a military settlement between Aske and the Duke of Norfolk, Aske was sent to London to explain himself, and while he was away, another uprising occurred in Cumberland and Westmoreland heading towards Yorkshire. Many in Parliament distrusted Aske's motives, and the King declared martial law, and under that guise initiated a massacre of rebels. At the same time, Aske was tried in London and executed for his crimes against the state. IV. Edward and Mary Tudor--two reigns, two dichotomous views A. Edward, the boy-king and his religious education by Katherine Parr. His mother was Jane Seymour who died of a botched caesarian just days after his birth. B. Developing a zealous Protestantism—as he was raised in the country, Edward came into contact with a zealous Protestantism. After his father's death, it is clear that Edward became even more "Protestant." While there remains some debate about who developed the Act of Uniformity as he was still quite young, it is important to note that Edward was intelligent and fully aware of his religious views. C. The Act of Uniformity (1549)—the act of uniformity was not fully accepted by the population. Before the Act, there were uprisings against the acts against enclosure in East Anglia (Suffolk and Norfolk), but it is the religious ferment in 1. the effects of the act in SW England—the instruction to accept only the book of common prayer resulted in spontaneous uprisings in Devon and Cornwall in the SW, which is often called the "Prayer Book Rebellion." Your reading for today has a vignette in which the affair began over the confiscation of a rosary, or prayer beads. While this is probably steeped in the folklore of the region after such a violent uprising in which many of the subjects were massacred, it is an important element in understanding historically the extent to which people first understood the Reformation and second accepted it. D. Mary's Accession and the reinstitution of hardline Catholicism—When Edward died in 1553, Lady Jane Grey ascended the throne for 9 days (we'll talk about her Sayegh lecture reformation struggle, page 4 in two weeks). Mary, however, bitter over the treatment of her mother, and a staunch RC her entire life V. Concluding Comments / discussion—next week we're going watch Man for All Seasons and see a dramatic interpretation of some of the politics of the age. Especially poignant will be the relationship between Sir Thomas More and Richard Rich…