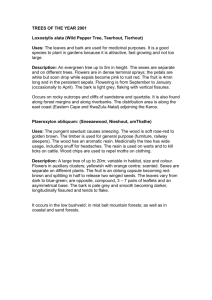

TurnipseedRoad_Nov09_gbp

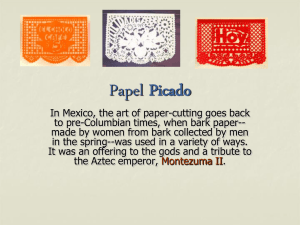

advertisement