Melanie`s notes from Donna Miller`s class

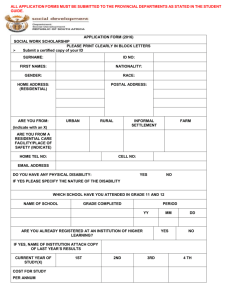

advertisement