A 1993 Hostile Review - Department of Psychology

advertisement

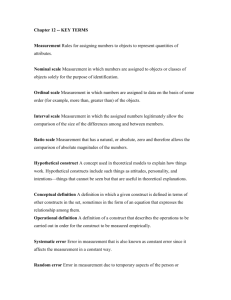

Back to Lie Detection Home Page honts_rev.doc Psychophysiology 317 VOLUME M AY 1993 NUMBER 3 Note: Original title of Hont's paper was: Heat without Light Our reply's title was: Rhetoric without Reason: Reply to Honts Editor removed both titles. Theories and Applications in the Detection of Deception. By Gershon Ben-Shakhar and John Furedy. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1990. 169 pages. Reviewed by Charles R. Honts, Psychology Department, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks In his review of Gale's (1988) volume on the detection of deception, Dawson (1990) noted that the longstanding controversy over the ability to detect deception from physiological recordings had "generated a higher ratio of heated debate to illuminating light" (p. 120) than had any other controversy in contemporary psychophysiology. Ben-Shakhar and Furedy's (1990) contribution to this polemic debate douses the flames with ethanol, thus palpably increasing the heat while adding very little illumination. The psychophysiological detection of deception is a very important area of application of psychophysiology. Polygraph tests have been and continue to be widely used in the United States in forensic, industrial, and national security settings, and all of those uses remain controversial. What is needed in the area of the psychophysiological detection of deception is critical analysis, integration, and theory development. Unfortunately, the present volume does not satisfy this need. The book contains 169 pages in nine chapters. Four of the chapters were authored primarily by Furedy, and five of the chapters were authored primarily by Ben-Shakhar. The content of the book is a compilation of a number of arguments and positions offered by the authors in a number of other publications. The book is unrelentingly critical of the control question test (CQT), practitioners who use the CQT, and researchers who, in the authors' opinions, waste their time attempting to study the CQT. However, the authors find the guilty knowledge test (more appropriately known as the concealed knowledge test [CKT], as knowledge cannot be guilty) to be of high merit, scientifically sound, and well researched. Disappointingly, there is little new material here and little real integration. It was particularly disappointing that no major new theoretical formulations were advanced in this volume. This book is characterized by five general themes. First, the CQT, although widely applied, does not contain scientific controls and therefore cannot be considered scientific. Second, the CQT is not standardized and therefore cannot be considered a test in the psychological sense of the term. Third, in practice the 318 Book reviews CQT is often contaminated by the polygraph examiner's interest in an interrogation and efforts toward obtaining a confession. Fourth, the CKT is preferable to CQT because it contains scientific controls and can be standardized. Finally, the utility of all polygraph tests must be evaluated through a specific effects analysis. These arguments have been enunciated in a book chapter by Furedy and Heslegrave (1991), and the reader should refer to a chapter in the same volume by Raskin and Kircher (1991), who provide detailed refutation of all but the third point. I see this book as marred by four nearly fatal flaws that are all too common in much of the commentary on the psychophysiological detection of deception. The first of these flaws concerns the use of the term validity and, in particular, a failure to differentiate between construct validity and criterion validity (Muchinsky, 1990). Construct validity refers to the theoretical constructs that are associated with a test or technique. For example, one might ask what psychophysiological processes are being measured by a CQT or CKT. Construct validity is assessed by theoretically oriented studies aimed at showing convergence with other measures of the same construct and divergence from measures of other constructs. Establishment of construct validity is one of the most interesting and difficult processes in psychological science. Criterion validity is a much simpler notion. Criterion validity simply asks how closely the outcome of some test is associated with some known real-world criterion. The area of the psychophysiological detection of deception is poor in theory development and therefore lags behind in construct validation, which thus hampers the development of programmatic research and may help explain the hodgepodge nature of the research literature. However, in application, criterion validity is of critical importance, and construct validity is of almost no concern. Construct validation is not necessary for the application of a technique, but criterion validity is. Ben-Shakhar and Furedy confuse these issues and condemn the control question test primarily on construct validation issues. From their perspective, it seems that because construct validation is lacking, criterion validation is a moot issue. However, if construct validation were necessary for successful application, medical science would have been denied the benefits of aspirin for decades. The second flaw in this book is that when the authors do consider criterion validity, they confuse the issue of the potential accuracy of a technique with the actual accuracy obtained in application. Ben-Shakhar and Furedy rightly condemn the state of training and practice of most polygraph examiners, but then so do most of the so-called proponents of lie detection (e.g., Honts & Perry, 1992; Raskin, 1986). The state of the practice of lie detection does leave much to be desired, and the authors do a thorough job of elucidating those problems. I thought that their comments about some law enforcement examiners being overly focused on obtaining confessions were particularly insightful. However, these issues of practice and application, although very important, are distinctly separate issues from the potential validity of a test. It is one thing to have a valid technique that is poorly applied and quite another to have a technique that is simply invalid. In the former condition, remediation is possible; in the latter it is not. Unfortunately, Ben-Shakhar and Furedy focus on issues of accuracy as applied and never recog- nize the critical distinction between practice and potential. It is simply not fair to condemn a technique as invalid if the real problems are practice issues. The third important problem concerns flaws in scholarship. I will give two examples. First, in discussing the issue of countermeasures the authors state, "It is notable that Elaad's (1987) results constitute the first demonstration that mental countermeasures have any effect on psychophysiological detection" (p. 73). However, there was a major study of mental countermeasures prior to the Elaad study (Honts, 1986). This omission is a notable flaw in scholarship, first because the results of Honts (1986) support Ben-Shakhar and Furedy's position on countermeasures and second because the Honts study was described in at least one work (Gale, 1988) cited in the present text. The Honts study was also described in other readily available sources (e.g., Honts, 1987) that were also not cited. The second scholarship example concerns a lack of discussion of techniques other than the control question and the relevant irrelevant tests. There are two alternative techniques that are used in the field, and they have been the subject of scientific study. One of those techniques is the directed lie control test, which has been in wide use for many years by military intelligence in the United States government and is gaining acceptance in general law enforcement. The directed lie control test was the subject of at least two studies (Barland, 1981; Horowitz, Raskin, Honts, & Kircher, 1988) that predate the Ben-Shakhar and Furedy text. The other technique they failed to discuss is the positive control test. The positive control test has been used for a number of years by several agencies in the United States government, and it has. also been the subject of at least two scientific studies (Driscoll, Honts, & Jones, 1987; Forman & McCauley, 1986) that predate the present volume. The omission of any discussion of these techniques in the present text is symptomatic of a lack of familiarity with the actual application of detection of deception techniques and with the scientific literature. The fourth flaw concerns the inconsistent manner with which Ben-Shakhar and Furedy approach laboratory and field data. In their analysis of the validity of the CQT, they dismiss all laboratory studies of CQT as being ecologically invalid. However, when they address the issue of countermeasures, they are more than willing to describe and use laboratory studies to indicate weakness in the CQT, while giving only lip service to the issue of ecological validity in that context. When considering the CKT, Ben-Shakhar and Furedy base their supportive arguments totally on laboratory data, much of it of more questionable ecological validity than the CQT laboratory studies they so strongly criticize. If laboratory studies are useful in estimating the validity of the CKT and the effectiveness of countermeasures, then they should be of use in estimating the validity of the CQT. Since the present book was published, a high-quality field study of the CKT has been published (Elaad, 1990) that indicates a very low accuracy (43<Po) of the CKT with guilty subjects. In summary, I found little in Theories and Application in the Detection of Deception to recommend it. If you are currently up on the controversy surrounding the detection of deception, you will have heard all of this before. If you are new to the area, this is not the place to start. REFERENCES Barland, G. H. (1981). A validity and reliability study of counterintelligence screening test. Fort George G. Meade, MD: Security Support Battalion, 902d Military Intelligence Group. Ben-Shakhar, G., & Furedy, J. J. (1990). Theories and applications in the detection of deception. New York: Springer-Verlag. Dawson, M. (1990). Where does the truth lie? A review of The poly- Book reviews graph test: Lies, truth, and science. Psychophysiology, 27, 120121. Driscoll, L. N., Honts, C. R., & Jones, D. (1987). The validity of the positive control physiological detection of deception technique. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 15, 46-50. Elaad, E. (1987). Psychophysio/ogical detection in the guilty knowledge test. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. Elaad, E. (1990). Detection of guilty knowledge in real-life criminal investigations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 521-529. Forman, R. R, & McCauley, C. (1986). Validity of the positive control polygraph test using the field practice model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 7/, 691-698. Furedy, J. J., & Heslegrave, R. J. (1991). The forensic use of the polygraph: A psychophysiological analysis of current trends and future prospects. In J. R. Jennings, P. K. Ackles, & M. G. H. Coles (Eds.), Advances in psychophysiology (Vol. 4, pp. 157189). London: Kingsley. Gale, A. (1988). The polygraph test: Lies, truth, and science. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. 319 Honts, C. .R. (1986). Countermeasures and the physiological detection of deception: A psychophysiological analysis. Dissertation Abstracts International, 47, 1761B. (Order No. DA8616081) Honts, C. R. (1987). Interpreting research on countermeasures and the physiological detection of deception. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 15, 204-209. Honts, C. R., & Perry, M. V. (1992). Polygraph admissibility: Changes and challenges. Law and Human Behavior, 16, 357379. Horowitz, S. W., Raskin, D. C, Honts, C. R., & Kircher, J. C. (1988). Control questions in physiological detection of deception. Psychophysiology, 25, 455. (Abstract) Muchinsky, P. M. (1990). Psychology applied to work. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Raskin, D. C. (1986). The polygraph in 1986: Scientific, professional and legal issues surrounding application and acceptance of polygraph evidence. Utah Law Review, 1986, 2974. Raskin, D. C, & Kircher, J. C. (1991). Comments on Furedy and Heslegrave: Misconceptions, misdescriptions, and misdirections. In J. R. Jennings, P. K. Ackles, & M. G. H. Coles (Eds.), Advances in psychophysiology (Vol. 4, pp. 215-223). London: Kingsley.