Chaos Theory and Its Implications for Counseling Psychology

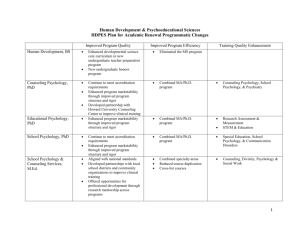

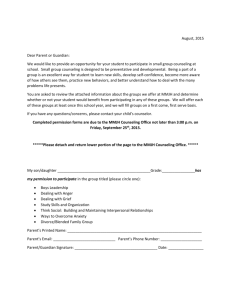

advertisement