Has Overweight Become the New Normal? Evidence of a

advertisement

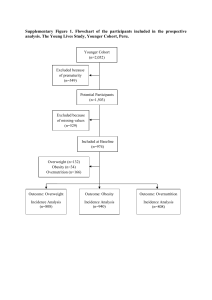

Has overweight become the new normal? Evidence of a generational shift in body weight norms August 27, 2008 Mary A. Burke Frank Heiland† Carl Nadler‡ Abstract We test for differences across the two most recent NHANES survey periods (1988-1994 and 1999-2004) in self-perception of weight status by observing different birth cohorts at the same age. We find that the probability of self-classifying as overweight is significantly lower, and the probability of self-classifying as underweight significantly higher, in the more recent survey, controlling for objective weight status and numerous socio-demographic factors. The shift in overweight self-classification appears most pronounced between the earlier and later cohorts of young adults (ages 17-35), while the shift in underweight selfclassification occurred largely across cohorts of adults ages 36-55. The evidence suggests that the weight range perceived as “normal” shifted to the right between the earlier and later surveys, perhaps as a response to the increase in average body mass index (BMI) in the population. Examining the data further, we show that the findings support a theoretical model (by two of the current authors) in which body weight norms vary directly with mean BMI in an individual’s social reference group. In particular, the younger age groups experienced the largest increases in mean BMI and obesity rates, and also had the sharpest declines in the tendency to self-classify as overweight. The differences in self-classification are not explained by differences across surveys in body fatness conditional on BMI, nor by the change that occurred between the survey periods in the CDC’s threshold for overweight. The welfare implications of the change in weight standards are ambiguous: if norms influence outcomes, obese individuals may now face weaker social incentives to lose weight; on the other hand, overweight and obese individuals may also benefit from greater socialand self-acceptance. Burke: Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 600 Atlantic Avenue, Boston, MA 02210, phone: 617-973-3066, e-mail: mary.burke@bos.frb.org. † Heiland: Deartment of Economics and Center for Demography and Population Health, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306-2180, e-mail: fheiland@fsu.edu. ‡ Nadler: Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 600 Atlantic Avenue, Boston, MA 02210, phone: 617-973-3096, e-mail: carl.nadler@bos.frb.org. 1 1. Introduction A large, multidisciplinary literature has investigated self-perceptions of body size and body shape, studying the determinants of these as well as their relationship to various aspects of physical and mental health. The bulk of the existing studies have focused on the (crosssectional) relationship between socio-economic characteristics and the self-perception of body weight appropriateness.1 Consequently, little is known about the evolution of body weight norms and ideals, either longitudinally within individuals or across different generations. Several recent articles have reported that significant percentages of individuals who would be classified by the CDC as either overweight or obese (on the basis of their BMI values) perceive their weight to be “normal”, “appropriate,” or “acceptable.” (See Rand and Resnick 2000; Chang and Christakis 2003; Neighbors and Sobal 2007; Howard et al. 2008). Neighbors and Sobal (2007, p.437), looking at a recent cohort of university students, conclude that “overweight females may not be seeking to attain the very thin sociocultural ‘ideal’ female form.” They speculate that body size ideals may be shifting, or at least that larger body sizes have become more acceptable as the population has become heavier. Recent work on the spread of obesity in social networks suggests, but cannot confirm, that weight gain may be “contagious” among friends because normative judgments of body size depend on—and so may change over time with—the size of our friends.2 In a previous theoretical paper (Burke and Heiland 2007), we posited that the social norm for body weight—defined as a reference point against which individuals judge the appropriateness of their own weight—varies directly with mean body weight in one’s social reference group. This framework predicts that the social weight norm in the United States would have increased over the past 20-30 years in response to the increase in actual mean body weight over the same period—between NHANES III (conducted over 1988-1994) and NHANES 1999-2004, mean BMI among individuals ages 17-74 increased by just over 6 percent, from 26.3 to 27.9, and the obesity rate jumped from 22 percent to 32 percent.3 If the weight norm in fact shifted across these periods, we might expect that the average individual observed today is (weakly) less likely to classify herself as overweight, and more likely to classify herself as underweight, than was a similar individual (at the same BMI value) observed 20 years ago The NHANES III and NHANES 1999-2004 surveys provide indirect information on weight norms with which we can test these predictions. In each of these surveys, people ages 17 to 1 Among socio-economic factors, race and ethnicity have been found to have sizable effects, with several studies reporting black-white differences in self-perceptions of body size and in body satisfaction. AfricanAmerican women tend to point to larger images for “ideal” size than do white (non-Hispanic) American women and they are more likely to perceive themselves as normal weight and less likely to be dissatisfied with their body weight and BMI compared with white women. For a survey of this literature, see Flynn and Fitzgibbon (1998); more recent studies include Lovejoy (2001) and Fitzgibbon, Blackman, and Avellone (2000) and Burke and Heiland (2008). 2 For details see Christakis and Fowler (2007), Trogdon et al. (2008), Fowler and Christakis (2008), Halliday and Kwak (2007), and Renna et al. (2008). 3 We argued that these weight gains were initiated by an exogenous decline in the full (money plus time) cost of food, and that a subsequent increase in the norm set off social multiplier effects that led to further increases in mean weight. In this paper we focus on the impact of mean BMI on weight norms. We discuss the identification issues raised by potential reverse causality further below. 2 74 were asked whether they consider themselves (at their current weight) to be either “underweight,” “about right,” or “overweight.”4 (The choice to self-classify as “obese” was not included.) Examining these responses, we find that the probability of self-classifying as overweight is indeed significantly lower, and—within some age ranges—the probability of self-classifying as underweight significantly higher, in the more recent survey, controlling for objective weight status and numerous socio-demographic factors. The shift in overweight self-classification appears most pronounced between the earlier and later cohorts of young adults (ages 17-35), while the shift in underweight self-classification occurred exclusively across cohorts of adults ages 36-55. We argue that our model of socially endogenous weight norms helps to explain the overall differences in self-classification tendencies between the survey periods and can explain some of the variation across age groups in the magnitude of such shifts. In particular, we find that members of groups (defined by age-range, sex, and birth cohort) with higher average BMI are less likely to classify themselves as overweight, and more likely to classify themselves as underweight, than are members of groups with lower average BMI, controlling for own BMI and other factors. In the empirical models, this relationship between peer-group BMI and self-perception can account for the differences in perception tendencies across surveys. For example, the more recent cohort of young adults (17-35) is both (a) heavier on average, and (b) less likely to classify themselves as overweight (conditional on actual weight), than was the previous cohort at the same age. Across cohorts of 36-45 year olds and 46-55 year olds, the increases in mean BMI and obesity rates were smaller than they were for the younger age ranges, as were the decreases in the tendency to classify as overweight.5 However, mean BMI at ages 56-74 was also higher in the later survey than the earlier survey, while the tendency to classify as overweight stayed roughly constant across the survey periods for this group. This inconsistency suggests that peers’ average BMI may have different impacts on norm formation at different ages. The self-perceptions of the young concerning their weight might be more malleable than the self-perceptions of older people, and therefore more susceptible to variation in reference-group-mean BMI. If childhood experience is particularly salient, generational differences in childhood obesity rates might also be linked to generational differences (in adolescence and into adulthood) in weight norms and self-reported weight classification. Unfortunately, we observe the relevant childhood obesity rates only for a subset of the adolescents and adults surveyed in NHANES III and NHANES 1999-2004, and within this subset the relevant rate is ambiguous in some cases. Using these limited observations, we find a correlation between childhood obesity rates and adult self-classification tendencies in the raw data, but multivariate regression analysis yields no significant relationship. 4 Beginning in 1999, respondents ages 16 to 74 were asked this question. For consistency we will consider only 17-74 year olds in both survey periods. 5 We also consider the impact of the contemporaneous obesity rate among the age-by-sex reference group on the self-classification of weight status, and find that higher peer obesity rates reduce the tendency to selfclassify as overweight. Due to collinearity, however, we cannot determine whether mean peer-group BMI or the peer-group obesity rate is the more important social reference point. 3 Some of the usual pitfalls associated with testing social interactions—such as simultaneity bias and endogenous peer selection—do not arise in this framework. First, the peer-group variables we use, including average BMI and the obesity rate in the peer group, are not aggregates of the dependent variable. Second, the social reference groups are exogenous because they are based only on age, sex, and birth cohort. While we cannot be certain that the peer variables do not merely proxy other common influences within social reference groups, models that substitute fixed effects of reference groups for average BMI (or the obesity rate) do not perform as well. We also consider the possibility that apparent changes in self-perception can be accounted for by changes in body fat percentage conditional on BMI. Self-judgments of weight status may depart from CDC standards, with good reason in some cases, because the standards are based on BMI and not body fat. If individuals assess their own weight status on the basis of fatness instead of, or in addition to, overall size, and if the average person today has a lower body fat percentage, conditional on BMI, than the average person in previous generations, we might expect people in the present to be less likely to classify as overweight, even with no change in social norms. As it happens, however, body fat percentage for the average individual, conditioned on BMI, has increased over time, and we find that observed differences in self-perception between the surveys are robust to controls for individual body fat percentage. It is also possible that changes in subjective assessments of underweight, normal weight, and overweight preceded the increases in mean BMI that occurred between the survey periods. Imagery in the popular media, public health messages, or scholastic content, for example, may have changed between the survey periods, promoting a larger body size ideal and a greater level of “fat acceptance” in particular. As far as official government standards go, the standard for overweight actually became stricter between the survey periods, not looser.6 Evidence on changes in media imagery is mixed. While the number of “plus-sized” female models has increased, images of women in popular media remain skewed to the left of average; emphasis on male appearance, and on ideal musculature in particular, seems to be growing. Educational programs in schools aimed at preventing eating disorders may have promoted healthier size ideals. If the shift in norms did in fact precede the shifts in the weight distribution, it remains a mystery why such an exogenous shift would have occurred. In some cases, the shifts in self-perception resulted in greater consistency with CDC standards: for example, the tendency of normal-weight individuals to self-classify as overweight declined across the surveys on average. In other cases, however, the shifts moved self-perceptions away from CDC standards, as overweight and obese people became less likely to self-classify as overweight than previously, especially among younger people. The welfare implications of the change in weight standards are ambiguous: if norms influence outcomes, obese individuals may now face weaker social incentives to lose weight; on the other hand, overweight and obese individuals may also benefit from greater socialand self-acceptance. 6 In 1998, on the recommendation of the World Health Organization, the CDC reduced the BMI thresholds for overweight, from 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women, down to 25 for both sexes. This new standard is applied retroactively when we measure rates of overweight and obesity in surveys conducted prior to 1998. 4 2. Objective vs. subjective weight status: how self-classification varies with age, sex, and survey period. Table 1 gives cross-tabulations of subjective weight status against CDC-defined (“objective”) weight status, separately by survey period and sex, for the full age range, from 17 to 74 years. The value in a given cell indicates the percentage of individuals in a given objective category (the row variable) that reported being in a given subjective category (the column variable). For example, in NHANES III, among women with normal BMI values, 56 percent considered their weight to be “about right” and 39 percent considered themselves to be “overweight.” For women in NHANES 1999-2004, the corresponding figures are 64 percent and 32 percent. Among women qualifying as overweight but not obese, 83 percent reported feeling overweight as of NHANES III, and only 78 percent said the same in 1999-2004. All of these differences across surveys are significant. For a given objective weight status and observation period, men are significantly less likely than women to self-classify as overweight and significantly more likely to classify as underweight. However, like women, men’s self-perceptions also shifted significantly across survey periods. For example, among overweight (but not obese) men, the share that self-classified as overweight fell from 59 percent in NHANES III to 53 percent in NHANES 1999-2004. Among obese men the share that considered themselves overweight fell from 89 percent to 84 percent.7 The trends in the tendency to self-classify as underweight offer less support for our theoretical model. Among women, for most of the objective weight categories we observe no significant increase between survey periods in the share that self-classified as underweight. Among men, the tendency to self-classify as underweight increased significantly among normal-weight individuals, but not for any of the other weight categories. Tables 2 and 3 replicate Table 1 for two different age groups: 17-25 year olds and 36-45 year olds. These tables show how the temporal changes in self-classification differ by age and gender.8 Observe in Table 2 that the difference in responses across the survey periods is more dramatic among young women ages 17-25 than for the female population as a whole: for this age group, the share normal-weight women that self-classified as overweight fell from 37 percent to 25 percent between the surveys, as compared to the decline from 39 percent to 32 percent for women overall. Among overweight young women, the share that self-classified as overweight fell by an estimated 14 percentage points, from 85 percent to 71 percent, while the decline for women as a whole was just 5 percentage points. Among obese young women the decline in the percentage classifying as overweight, from 95 percent to 84 percent, was also larger than the corresponding decline for women in general. Of course, the standard errors on the estimates for young women are greater than those for the female 7 These differences in self-reporting conditional on weight status cannot be explained by decreases in average BMI conditional on the objective weight category, since the conditional means either remained constant or increased between the survey periods. 8 Objective weight status for 17-20 year olds is determined using the CDC’s reference distributions, which are gender and age specific. At a given gender and age, underweight is defined as below the 5 th percentile of the relevant BMI distribution, between 5th and 85th is defined as normal, 85th to 95th is considered overweight but not obese, and 95th and above is obese. Cutoff points by age and sex are shown in the data appendix, Table A.2. 5 population as a whole, so these differences in differences may be less than what the point estimates indicate. Among normal-weight men ages 17-25, the share that considered themselves overweight did not differ significantly across the surveys. However, among overweight (not obese) young men, the share that self-classified as overweight fell significantly, from 51 percent to 42 percent; and among obese young men, the share that classified themselves as overweight fell dramatically, from 90 percent to 71 percent. Among young people of either sex, we observe a significant increase in the tendency to self-classify as underweight only among obese individuals. For the 36-45 year olds, seen in Table 3, a few different patterns emerge. First, notice that the decline in the tendency of women to self-classify as overweight is less pronounced than it was among 17-25 year olds. Among normal-weight women in particular, the share that considered themselves overweight was 41 percent in both survey periods. For men in this age group, we see some significant declines in the tendency to self-classify as overweight, but only among normal-weight and overweight men and not also among obese men. This last fact stands in stark contrast to the large decrease across the surveys, noted above, in the percentage of men ages 17-25 that considered themselves overweight. The trends in underweight self-classification also differed between 17-25 year olds and 36-45 year olds. Among normal-weight men age 36-45, the proportion that self-classified as underweight increased from 9 percent to 19 percent, a difference that is highly significant. For underweight women and underweight men alike, the share that self-classified as underweight increased by potentially large margins between the surveys, although the estimates of the respective differences are not very precise. Table 4 juxtaposes the changes in actual BMI, current obesity rates, and childhood obesity rates across surveys, by age group, against the changes in the probabilities of self-classifying as overweight, conditional on being overweight (but not obese) and conditional on being obese. Inspecting the table, we see that the youngest age bracket, for both males and females, experienced the largest gains in the childhood obesity rate between surveys as well as the biggest declines in the conditional probabilities of self-classifying as overweight. The youngest male group also had the biggest increase in mean BMI across the surveys, although increases in obesity rates across the surveys were greatest for the second-youngest group for both sexes. Also complicating the picture, we observe that the oldest age bracket of either sex showed large increases across the surveys in mean BMI and contemporaneous obesity rates, while at the same time becoming more likely to self-classify as overweight. 3. Multivariate regression analysis The differences in weight perception across the surveys shown in the tables above do not control for differences across the survey periods in characteristics that may influence survey responses, such as educational attainment, race/ethnicity, and household income. In addition, we would like to test the hypothesis that differences across surveys in the self-classification of body weight reflect a generational shift in weight norms induced by differences in average 6 BMI across birth cohorts. To address these issues, we conduct a multinomial logit analysis of the survey responses, adopting various model specifications. The dependent variable is the response to the NHANES self-perception question, which can take on one of three values: “underweight”, “about right,” or “overweight.” In our theoretical model (Burke and Heiland 2007), the weight norm is defined as a specific point value, and thresholds for overweight and underweight are not defined. (Rather, utility is decreasing in the squared difference between own weight and the norm, such that “overweight” is a matter of degree and not an either-or proposition.) In contrast, the NHANES survey question forces individuals to adopt implicit thresholds for overweight and underweight. Extending our conceptual framework slightly, we can replace the point-value norm with a range of weights deemed “about right” and assume that the lower and upper boundaries of this range depend directly on average weight (BMI) in the reference population. Under these assumptions, the probability that an individual self-classifies as overweight should be increasing (weakly) in her own BMI and decreasing (weakly) in the mean BMI of her social peer group, ceteris paribus. Likewise, the probability that someone self-classifies as underweight should be weakly decreasing in her own BMI and weakly increasing in mean peer-group BMI. We will define peer groups quite broadly, as all others in the same age category and the same sex as of the same survey period. Empirical setup We adopt a multinomial logit specification that predicts the probability of each survey response. The baseline response is “about right” and results are reported as coefficients of relative risk. To test the significance of differences in responses across survey periods, we pool the data from the NHANES III and NHANES 1999-2004 surveys, and create a dummy variable to indicate the survey period from which a given observation is taken.9 To allow for non-linear age effects, we construct five discrete age categories: 17-25, 26-35, 36-45, 46-55, and 56-74, which are roughly equal in terms of their weighted share of the combined NHANES data. (In an alternative specification we let age enter as a continuous variable.) In what we will call the “baseline model,” we do not test for social effects related to average BMI or obesity rates in peer groups. In three subsequent models, we add, alternately, one of three different reference-group variables or “social interaction” terms, where reference groups are defined on the basis of age range, sex, and survey period. These include (i) the contemporaneous average BMI in the reference group, (ii) the contemporaneous obesity rate in the reference group, and (iii) the estimated obesity rate (explained below) that prevailed among the reference group when they were children ages 6-11. All models include the following explanatory variables: a dummy variable for female, a dummy variable for observations taken from NHANES 1999-2004, an interaction term between the female dummy and the survey dummy, dummies for each age range (where 369 According to Korn and Graubard (1999), it is not necessary to re-weight the data when pooling NHANES surveys, based on the assumption that the samples are independent across the periods. We control for complex survey design within each survey using the appropriate strata and primary sampling unit (PSU) variables. Using Stata’s “svy” commands, the data are weighted correctly and the standard errors are clustered appropriately. 7 45 is the omitted category), interaction terms between each age range and the survey period, race/ethnicity dummy variables (white non-Hispanic, African American non-Hispanic, Mexican-American, and other), individual BMI (treated as a continuous variable), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate, or some college or better), household income (three discrete categories based on the relationship to poverty-line income), and marital status (currently married, formerly married, never married). The construction of these variables is discussed in a data appendix. Sample means of these variables by sex, pooled across surveys, are shown in Table A.1. Main results Table 5 shows the results of the four different models. The baseline model (“Model 1”), includes just the list of explanatory variables given directly above. The “mean BMI” model (“Model 2”) includes the baseline variables plus the contemporaneous mean BMI for the individual’s reference group (defined above). The “obesity rate” model (“Model 3”) includes the baseline variables plus the contemporaneous obesity rate in the reference group, and the “childhood obesity” model (“Model 4”) includes the baseline variables and the estimated childhood obesity rate for the reference group. In the following discussion we focus on the variation in self-classification tendencies with the survey variable, with interactions between the survey variable and age, and, from models 2-4, we focus on the impact of the referencegroup variables. First, observe the results of the baseline model pertaining to the relative risk of selfclassifying as “underweight.” The “NHANES 1999-2004” dummy has a highly significant coefficient estimated at 2.4. Given the age-survey interaction terms, this result means that, within the 36-45-year-old age group, the relative risk of self-classifying as underweight (compared to the risk of self-classifying as “about right”) was about 2.4 times as great on average among those observed in the later survey period as it was among those ages 36-45 observed in the earlier period.10 This difference across surveys may have been weaker among women, but the significance level of .085 on the interaction coefficient renders this statement uncertain. However, there are significant interaction coefficients between the NHANES 1999-2004 dummy and each of three other age categories (17-25, 26-35, and 5674), each with a value significantly less than one. These results mean that these other age groups experienced either a significantly less pronounced increase in the tendency to selfclassify as underweight, or even a decrease in this tendency (as may have occurred among 17-25 year olds), between the earlier and later surveys. Notice also that, in line with objective classifications, the relative risk of self-classifying as underweight is smaller the higher is an individual’s BMI value. Also as we might expect, women and people with high household incomes have significantly lower relative risks of classifying as underweight, respectively, than men and those in the lowest-income group do. African Americans are significantly more likely than whites to self-classify as underweight. Now consider the impact of the reference-group variables on the relative risk of selfclassifying as underweight (Table 5, Models 2-4). Most of the coefficient estimates are 10 Fixed survey effects can be misleading in this model, as the survey differences vary considerably across BMI values. This variation is illustrated in Figures 1-5. 8 quantitatively and qualitatively similar to those in the baseline model. However, in model 2, the main effect of the NHANES 1999-2004 variable is no longer significant and mean BMI in the reference group has a coefficient that is significantly greater than one. This latter result indicates that, the higher is average BMI in the reference group, the greater is the relative risk that an individual self-classifies as underweight. This agrees with the logic of the social interactions model: the heavier are your peers, the more likely you are to feel underweight by comparison. The insignificance of the main survey effect in this model suggests that social interactions may account for the fact that 36-45 year olds were more likely to self-classify as underweight in the later survey than in the earlier survey. That is, average BMI was higher for this age group in the later survey than in the earlier survey (see Table 6), and as a result the more recent cohort of 36-45 year olds is more likely to feel underweight. However, including mean BMI in the model does not wipe out the coefficient on the interaction term, for example, between age 17-25 and NHANES 1999-2004. That is, despite the fact that mean BMI also increased across survey periods for the age group 17-25 years as shown in Table 6, the more recent crop of 17-25 year olds are not more likely than their predecessors to self-classify as underweight. The results of model 3 are similar to those of model 2 in that the main survey effect becomes insignificant and other coefficients are largely unchanged. The estimated coefficient on the reference-group’s obesity rate is greater than one, consistent with the notion that having a greater share of obese peers will make people feel relatively underweight. However, this estimate is significant only at the 0.07 level, so we cannot have great confidence in the strength of this effect. In model 4 we include the estimated childhood obesity rate by agesex-survey cohort. The significance of the main survey effect is restored, and we find no significant influence of the childhood obesity rate on the tendency to self-classify as underweight. Due to data constraints, the sample size was significantly reduced in model 4 relative to model 3, and we cannot be confident in the accuracy of the survey weights within the resulting sub-sample. We do not believe that the results of model 4 rule out the possibility that childhood obesity rates influence self-perceptions into adulthood. Now observe the results of the baseline model pertaining to the relative risk of selfclassifying as “overweight” as opposed to “about right.” The NHANES 1999-2004 dummy variable again has a significant coefficient, but now its value is significantly less than one. This means that, among 36-45 year olds, the relative risk of self-classifying as overweight was about 30 percent lower on average in the later survey period than in the earlier period, all else equal. The age-survey interaction terms indicate that, for the two youngest age groups (17-25 and 26-35), the tendency to self-classify as overweight fell by an even greater percentage between NHANES III and 1999-2004. The difference in self-classification tendencies across surveys was roughly the same for 46-55 year olds as for 36-45 year olds, given that the interaction between “age 46-55” and “NHANES 1999-2004” is not significant. However, for the oldest group (ages 56-74), the significant interaction coefficient of 1.36 offsets the main survey effect, and the net estimate is that the relative tendency to selfclassify as overweight did not change significantly across the surveys. The remaining effects in the baseline model are largely in line with expectations. Higher BMI increases the risk that an individual classifies as overweight. Women are more likely to 9 self-classify as overweight than men, better-educated groups are more likely to feel overweight than the least educated, and those with middle and high incomes are more likely to feel overweight than those with the lowest incomes. Those currently married are more likely to feel overweight than never-married people, and minority groups are significantly less likely than whites are to consider themselves overweight. Again we find evidence that average BMI in reference groups may explain differences in self-classification tendencies across surveys. Looking at the results of Model 2, observe that mean reference-group BMI has a coefficient that is less than one (0.72), significant at the .051 level. (The 95 percent confidence interval ranges from 0.52 to 1.00). This means that those in groups (age-by-gender-by-cohort) with higher average BMI have a lower relative risk of self-classifying as overweight, all else equal. At the same time, the main survey effect becomes insignificant, the interaction term between “age 26-35” and “NHANES 1999-2004” becomes insignificant, and the interaction term between “age 17-25” and the survey dummy becomes only marginally significant (p-value of .085). These results suggest that higher mean BMI values among the more recent cohorts in these age ranges may have given rise to different perceptions, among these same cohorts, of what range of sizes should be considered normal and at what point one becomes overweight. In Model 3, the contemporaneous obesity rate among peers is negatively related to the relative risk of self-classifying as overweight, and the main survey effect is insignificant. However, unlike the results from Model 2, the significant interaction effects observed in the baseline model, between the NHANES 1999-2004 dummy and the various age groups, remain significant in Model 3. Taking these results at face value, we infer that peer obesity rates explain differences across surveys in the tendency to self-classify as overweight only for the 36-45 year old group; for the other groups the differences across surveys cannot be fully explained by differences across cohorts in obesity rates. In Model 4, the cohort-specific childhood obesity rate wields no significant effect on the relative risk of self-classifying as overweight, nor does it account for the main survey effect (pertaining to 36-45 year olds) observed in the baseline model. We note that the peer variables do not seem to explain some of the fixed differences across age groups in self-perception tendencies that are indicated by the age-group fixed effects, Within the NHANES III survey period, those in the youngest group are significantly more likely (than were those in the reference age group ages 36-45) to consider themselves underweight, and those ages 56-74 are significantly more likely to consider themselves overweight, even controlling for average BMI or the obesity rate in the relevant peer group. Netting out survey effects and age-survey interactions, these age differences are at least qualitatively similar as of NHANES 1999-2004. We interpret these as life-cycle effects: young people, and young men in particular, may be more likely to consider themselves underweight because they are not yet fully grown. Also, people tend to gain weight as they get older, and may (consciously or not) find it psychologically convenient to adjust their standard of overweight. Graphical illustration of results 10 Because we are using a multinomial logit model, it is helpful to illustrate the model results graphically. Figures 1 through 5 provide such illustrations, using the results of our baseline model. Figure 1 shows the predicted probability of each outcome as a function of BMI for women ages 17-25, separately by survey period (top panel), and does the same for men ages 17-25 (bottom panel). Figures 2 and 3 repeat this exercise for 36-45 year olds and 56-74 year olds, respectively. Figures 4 and 5 compare predicted responses between the youngest group (17-25) and the middle age group (36-45) within each survey period, separately by sex, to highlight age differences in self-classification and changes in these age differences over time. The appropriate values for BMI, gender, and the survey dummy are assigned, and all other variables are held at their sex-specific sample means, reported in Table A1. Note that these means are not survey-specific but rather reflect average values across all individuals observed in both surveys. In these plots, the only source of differences in predicted probabilities between the survey periods derives from the NHANES 1999-2004 fixed effect and the interaction term between the given age bracket and the NHANES 1999-2004 dummy. The vertical lines in each figure indicate the boundaries between the “objective” weight categories as defined by the CDC. Moving from left to right we have, respectively, the boundary between underweight and normal weight, that between normal weight and overweight, and that between overweight and obese. However, in the plots that refer to people under age 21, we draw two different boundaries for each demarcation. This is because the boundaries differ between adults (ages 21 and over) and adolescents (ages 17-20, in our sample). For adolescents, there are in fact different cutoff points at each specific age. However, we show only the lowest boundary for each category, the purple line pertaining to 17 year olds, together with a black line pertaining to adults. Age-specific cutoffs defining each category are shown in Table A2. Comparing figures 1, 2, and 3, we see readily that the differences across surveys in the predicted probabilities of responding “about right” or “overweight” are greatest for the youngest age group. For the oldest age group the predicted responses are virtually identical across the survey periods. However, we see a significant increase across the surveys in the likelihood of responding “underweight” only among the 36-45 year old group. The pictures also illustrate the stark differences between men and women in self-perception of weight status, as well as the significant gaps between subjective and objective classifications. 4. Discussion Alternative explanations The CDC’s weight classification system considers only total body mass and not fat mass specifically, the latter being the stronger predictor of health risks. While BMI and fatness are correlated, adiposity and related health risks can vary considerably between individuals with the same BMI. Some people with BMI values that qualify as “overweight” or “obese” have very low levels of body fat, and some with “normal” BMI values have very high levels of body fat. This disconnect between BMI and adiposity may be especially acute among teenage boys (Sardinha et al. 1999). If self-judgements of weight status are based on fatness rather than on BMI, then the observed discrepancies between subjective and “objective” weight status may simply reflect the limitations of the BMI-based system, and need not 11 indicate any distorting social influences. In addition, shifts over time in self-classification could reflect shifts in underlying fatness conditional on BMI. If the average young person today has a lower body fat percentage, at a given BMI value, than the average young person in previous generations at the same BMI, we might expect today’s young person to be less likely to classify as overweight, even with no change in social norms. NHANES examination data enable us to compute body fat percentage for a significant share of our sample. When we add controls for individual body fat percentage to our empirical models (each of Models 1 through 4 described above), we find that our results are largely robust. Even a casual analysis predicts that this should be the case. Conditional on BMI, the average body fat percentage increased between the surveys rather than decreased. In light of this development, self-perceptions based on fatness would have tended toward peoples’ feeling fatter at a given BMI rather than less overweight. It is also possible that changes in subjective assessments of underweight, normal weight, and overweight preceded the increases in mean BMI that occurred between the survey periods. Imagery in the popular media, public health messages, or scholastic content, for example, may have changed between the survey periods, promoting a larger body size ideal and a greater level of “fat acceptance” in particular. Evidence on media imagery is mixed (see Turner et al. 1997; Holmstrom 2004; Greenberg and Worrell, 2005). While the number of “plus-sized” female models has increased, images of women in popular media remain skewed to the left of average; emphasis on male appearance, and on ideal musculature in particular, seems to be growing in the popular media. As far as official government standards go, the standard for overweight actually became stricter between the survey periods, not looser.11 Following the shift in CDC standards, individuals with BMI values between 25 and 27, for example, should have been more likely to classify as overweight in the later survey. In the past decade, however, numerous government programs have emerged that promote the development of a “healthy” body image and healthy eating behavior. For example, the National Eating Disorders Association offers the educational program “GO GIRLS!” and the U.S. Department of Health offers a “Healthy Body Image” book for use in public schools.12 These latter programs, at least, appear to promote more realistic self-assessments of weight, among girls in particular, as a preventive measure against eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Also in recent years, however, several states have come to require that children and adolescents in public schools be weighed and measured.13 Parents and children are then informed of the child’s official weight status and, in the case of overweight and obese children, advised to adopt healthier habits and target a healthier weight. Therefore, 11 In 1998, on the recommendation of the World Health Organization, the CDC reduced the BMI thresholds for overweight, from 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women, down to 25 for both sexes, and reduced the threshold for “severe overweight” from 31.1 for men and 32.2 for women to an “obesity” threshold of 30 for both sexes. These new standards are applied retroactively when we measure rates of overweight and obesity in surveys conducted prior to 1998. See http://win.niddk.nih.gov/statistics/#whydodiffer 12 The “GO GIRLS!” program “engages high school girls (and boys too!) to advocate for positive body images of youth in advertising, the media and major retailers.” See http://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/programsevents/educational-programs.php#go-girls. The “Healthy Body Image” book is part of the “BodyWise” information kit distributed by The U.S. Department of Health, Office of Women’s Health. 13 See http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/obesity/BMI/pdf/BMI_execsumm.pdf 12 overweight students may be receiving mixed messages: on the one hand, to lose weight, and on the other hand, to have a healthy self-image. The net impact of such messages on selfassessments among children and adolescents remains unclear. Policy and welfare implications We have identified a number of significant shifts in the self-classification of body weight between the NHANES III and 1999-2004 survey periods. We have argued that such shifts reflect socially endogenous differences in body weight norms that arose across birth cohorts in response to differences in mean BMI and obesity rates across these same cohorts. The endogeneity of weight norms in general, as well as the specific changes in conceptions of body weight that we observe, hold implications for policy-makers and for individual wellbeing. While we have not in this paper stressed the influence of body weight norms on individual weight outcomes, if such an influence is significant, the possibility of selfreinforcing feedback loops arises. For example, as we describe in our earlier work (Burke and Heiland 2007), a decline in food prices exerts a direct (positive) impact on average body weight, which leads (with some time lag) to an upward adjustment of weight norms, leading to a further upward adjustment of average weight, and so on until an equilibrium point is restored. Policy interventions that aim to reduce obesity may be able to harness the influence of this ‘social multiplier’ effect. On the other hand, our framework implies that government messages may hold little sway over de facto weight norms, as evidenced by the considerable discrepancies between subjective and objective classifications, and also that the influence of popular media on subjective weight assessments may be overstated. We observe that women’s notion of overweight (excepting 56-74 year olds) has become less strict and now shows stronger agreement with CDC standards—see, in particular, Figures 1 and 2. However, a larger share of overweight and obese men and women (defined using BMI) now classify themselves as “about right,” an indication that such individuals believe that they do not need to lose weight. Such judgments could be beneficial on net, especially for individuals who are merely overweight and not obese or severely obese. Against the health costs of being overweight, one must weigh the costs of dieting and the mental health costs of negative self-image. Public policy on obesity to date has focused too narrowly on BMI and not on more fundamental risk factors such as body fat, nutrition, physical activity, and mental health. 13 References Burke, M.A., and F. Heiland (2007). Social Dynamics of Obesity, Economic Inquiry, 45(3):571-591. Burke, M.A., and F. Heiland (2008). Race, Obesity, and the Puzzle of Gender-Specificity, Florida State University Working Paper. Chang, Virginia W. and Nicholas A. Christakis (2003). Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 24(4):332339. Christakis, N.A., Fowler, J.H. (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 Years, The New England Journal of Medicine, 357(4):370-379. Fitzgibbon, M. L., Blackman, L. R., and M. E. Avellone (2000), The Relationship Between Body Image Discrepancy and Body Mass Index Across Ethnic Groups, Obesity Research 8(9):582–589. Flegal, Katherine M., Graubard, Barry I., Williamson, David F., and Mitchell H. Gail. (2007). Cause-Specific Excess Deaths Associated With Underweight, Overweight, and Obesity, JAMA, 298(17):2028-2037. Flynn, K. J., and M. Fitzgibbon (1998), “Body Images and Obesity Risk among Black Females: A Review of the Literature,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 20(1):13–24. Fowler, J.H., Christakis, N.A. (2008). Estimating Peer Effects on Health in Social Networks, Journal of Health Economics. Forthcoming. Greenberg, Bradley A., and Tracy R. Worrell (2005). The Portrayal of Weight in the Media and Its Social Impact. In: Weight Bias. Nature, Consequences, and Remedies, edited by Kelly D. Brownell, Leslie Rudd, Marlene B. Schwartz, Rebecca M. Puhl, New York, London: The Guilford Press, pp. 42-53. Greenleaf, Christy, Heather Chambliss, Deborah J. Rhea, Scott B. Martin, and James R. Morrow Jr (2006). Weight Stereotypes and Behavioral Intentions toward Thin and Fat Peers among White and Hispanic Adolescents, Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(4):546-552. Halliday, T.J., Kwak, S. (2007). Identifying endogenous peer effects in the spread of obesity. University of Hawaii at Manoa Working Paper. Holmstrom, Amanda J. (2004), The Effects of the Media on Body Image: A Meta-Analysis, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48(2):196-217. 14 Howard, Natasha J., Graeme J. Hugo, Anne W. Taylor, and David H. Wilson (2008). Our perception of weight: Socioeconomic and sociocultural explanations, Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 2:125-131. Korn, Edward L. and Barry I. Graubard (1999). Analysis of Health Surveys. New York: Wiley, 279-300. Lovejoy, M. (2001). Disturbances in the Social Body: Differences in Body Image and Eating Problems among African American and White Women, Gender and Society, 15(2):239–261. Neighbors, Lori A., and Jeffery Sobal (2007). Prevalence and magnitude of body weight and shape dissatisfaction among university students, Eating Behaviors, 8(4):429-439. Ogden, Cynthia L., Katherine M. Flegal, Margaret D. Carroll, et al. (2002). Prevalence and Trends in Overweight Among US Children and Adolescents, 1999-2000, JAMA, 288(14):1728-1732. Ogden, Cynthia L., Margaret D. Carroll, Lester R. Curtin, et al. (2006). Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in the United States, 1999-2004, JAMA, 295(13):1549-1555. Renna, F., Grafova, I.B., Thakur, N. (2008). Effect of Friends on Adolescent Weight Status. University of Akron Working Paper. Rand, C. S. W., and J. Resnick. (2000). The ‘Good Enough’ Body Size as judged by People of varying Age and Weight, Obesity Research, 8, 309-316. Sardinha, Luis B, Scott B. Going, Pedro J. Teixeira, and Timothy G. Lohman (1999). Receiver operating characteristic analysis of body mass index, triceps skinfold thickness, and arm girth for obesity screening in children and adolescents, American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1999; 70:1090–1095. Trogdon, J.G., Nonnemaker, J., Pais, J. (2008). Peer effects in adolescent overweight, Journal of Health Economics. Forthcoming. Turner, Sherry L., Hamilton, Heather, Jacobs, Meija, Angood, Laurie M., and Deanne Hovde Dwyer (1997). The Influence of Fashion Magazines on the Body Image Satisfaction of College Women: An Exploratory Analysis, Adolescence, 32: 15 Table 1. Weight Perception, Age 17-74 Underweight BMI Category Underweight Normal Overweight Obese Total Real Rates BMI Category Underweight Women 17-74, NHANES III About Right Overweight Total Underweight 43.72 (5.13) 4.57 (0.36) 0.46 (0.10) 0.22 (0.13) 3.93 (0.25) 3.66 (0.36) 56.28 (5.13) 55.99 (1.33) 16.18 (1.19) 3.74 (0.46) 33.53 (0.96) 47.51 (1.11) 0.00 (0.00) 39.44 (1.30) 83.36 (1.16) 96.04 (0.47) 62.54 (1.00) 48.83 (1.11) 100.00 BMI Category Underweight 100.00 Normal 100.00 Overweight 100.00 Obese 100.00 Total 100.00 Real Rates Underweight About Right Overweight Total Men 17-74, NHANES III About Right Overweight Total 73.64 (4.99) 15.65 (1.12) 0.70 (0.23) 0.58 (0.36) 7.91 (0.55) 1.40 (0.22) 26.36 (4.99) 73.84 (1.22) 40.72 (1.34) 10.80 (1.48) 48.49 (0.80) 41.49 (1.12) 0.00 (0.00) 10.51 (0.85) 58.58 (1.36) 88.63 (1.60) 43.60 (0.87) 57.11 (1.07) 100.00 Underweight About Right Overweight Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 BMI Category Underweight 48.97 49.93 1.10 100.00 72.88 27.12 0.00 100.00 (5.25) (5.38) (1.08) (5.51) (5.51) (0.00) Normal 3.80 63.74 32.46 100.00 Normal 18.75 73.72 7.53 100.00 (0.33) (1.16) (1.13) (1.03) (1.13) (0.73) Overweight 0.31 22.04 77.66 100.00 Overweight 1.19 46.05 52.76 100.00 (0.10) (1.13) (1.16) (0.28) (1.52) (1.53) Obese 0.50 6.45 93.05 100.00 Obese 1.03 15.06 83.90 100.00 (0.14) (0.60) (0.63) (0.31) (1.23) (1.36) Total 2.86 32.54 64.60 100.00 Total 7.65 45.24 47.11 100.00 (0.20) (0.82) (0.79) (0.41) (0.78) (0.74) Real Rates 2.49 36.53 60.98 100.00 Real Rates 1.46 31.15 67.39 100.00 (0.24) (0.93) (0.93) (0.17) (0.75) (0.76) Notes: Coefficients represent the share of individuals who perceive themselves as “Underweight,” “About Right,” or “Overweight” by BMI categories. Standard errors are in parentheses. 16 Table 2. Weight Perception, Age 17-25 Women 17-25, NHANES III About Underweight Right Overweight BMI Category Underweight Normal Overweight Obese Total Real Rates 41.55 (6.95) 7.34 (1.25) 0.48 (0.28) 0.00 (0.00) 7.39 (0.80) 6.20 (0.97) 58.45 (6.95) 55.40 (2.43) 14.95 (3.36) 5.34 (2.45) 42.47 (1.85) 64.39 (2.07) 0.00 (0.00) 37.25 (2.63) 84.57 (3.36) 94.66 (2.45) 50.14 (2.09) 29.40 (1.82) Total Underweight 100.00 BMI Category Underweight 100.00 Normal 100.00 Overweight 100.00 Obese 100.00 Total 100.00 Real Rates Women 17-25, NHANES 1999-2004 About Underweight Right Overweight Total BMI Category Underweight 79.91 (7.11) 25.32 (2.67) 1.13 (0.43) 0.19 (0.19) 19.48 (2.04) 3.65 (0.79) Men 17-25, NHANES III About Right Overweight 20.09 (7.11) 67.85 (2.82) 47.38 (4.26) 9.48 (2.61) 55.03 (2.11) 64.45 (1.90) 0.00 (0.00) 6.84 (1.30) 51.49 (4.17) 90.33 (2.62) 25.49 (1.85) 31.90 (1.79) Men 17-25, NHANES 1999-2004 About Underweight Right Overweight Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 Total BMI Category Underweight 32.03 67.97 0.00 100.00 71.74 28.26 0.00 100.00 (8.79) (8.79) (0.00) (6.72) (6.72) (0.00) Normal 5.17 70.00 24.83 100.00 Normal 23.69 71.12 5.19 100.00 (0.71) (1.74) (1.75) (1.83) (1.75) (0.90) Overweight 0.36 28.44 71.21 100.00 Overweight 1.21 56.41 42.39 100.00 (0.35) (3.51) (3.53) (0.60) (3.53) (3.39) Obese 1.01 14.62 84.37 100.00 Obese 2.02 27.44 70.54 100.00 (0.61) (2.72) (2.75) (1.17) (2.17) (2.40) Total 4.39 49.59 46.02 100.00 Total 15.11 56.32 28.57 100.00 (0.56) (1.73) (1.65) (1.10) (1.45) (1.33) Real Rates 3.93 54.81 41.25 100.00 Real Rates 3.71 49.59 46.70 100.00 (0.65) (1.42) (1.37) (0.74) (1.37) (1.27) Notes: Coefficients represent the share of individuals who perceive themselves as “Underweight,” “About Right,” or “Overweight” by BMI categories. Standard errors are in parentheses. 17 Table 3. Weight Perception, Age 36-45 Women 36-45, NHANES III About Underweight Right Overweight BMI Category Underweight Normal Overweight Obese Total Real Rates 34.33 (11.59) 2.32 (0.68) 0.26 (0.21) 0.75 (0.53) 2.43 (0.56) 3.19 (0.62) 65.67 (11.59) 56.66 (2.92) 9.56 (2.31) 2.35 (0.55) 31.37 (2.36) 46.49 (2.49) 0.00 0.00 41.02 (2.79) 90.18 (2.33) 96.90 (0.70) 66.20 (2.34) 50.32 (2.45) Total Underweight 100.00 BMI Category Underweight 100.00 Normal 100.00 Overweight 100.00 Obese 100.00 Total 100.00 Real Rates Women 36-45, NHANES 1999-2004 About Underweight Right Overweight Total BMI Category Underweight 74.40 (15.10) 9.34 (1.71) 0.42 (0.18) 1.37 (1.31) 4.43 (0.74) 1.06 (0.45) Men 36-45, NHANES III About Right Overweight 25.60 (15.10) 74.85 (3.01) 38.04 (3.70) 11.99 (3.13) 44.51 (2.22) 33.61 (1.88) 0.00 0.00 15.81 (2.73) 61.53 (3.69) 86.64 (3.40) 51.06 (2.16) 65.33 (1.89) Men 36-45, NHANES 1999-2004 About Underweight Right Overweight Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 Total BMI Category Underweight 64.68 29.74 5.58 100.00 95.16 4.84 0.00 100.00 (12.72) (12.85) (5.06) (4.27) (4.27) 0.00 Normal 2.63 56.37 41.01 100.00 Normal 19.15 72.50 8.35 100.00 (0.63) (3.15) (2.90) (2.37) (2.86) (1.78) Overweight 0.37 17.34 82.29 100.00 Overweight 2.56 47.65 49.79 100.00 (0.23) (2.57) (2.57) (0.94) (3.73) (3.69) Obese 0.39 5.40 94.21 100.00 Obese 0.00 12.39 87.61 100.00 (0.23) (0.93) (0.92) 0.00 (1.81) (1.81) Total 2.62 26.66 70.72 100.00 Total 7.07 42.61 50.31 100.00 (0.51) (1.58) (1.46) (1.02) (1.86) (2.03) Real Rates 2.28 34.34 63.38 100.00 Real Rates 0.87 27.30 71.83 100.00 (0.51) (1.93) (2.07) (0.46) (1.46) (1.53) Notes: Coefficients represent the share of individuals who perceive themselves as “Underweight,” “About Right,” or “Overweight” by BMI categories. Standard errors are in parentheses. 18 Table 4. Differences in Means and Probabilities, NHANES 1999-2004 - NHANES III Age Range Men 17-74 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 BMI 1.600 (0.216) 1.260 (0.268) 1.001 (0.315) 1.199 (0.313) 1.292 (0.214) Obesity Rate * 8.190 (2.062) * 8.855 (2.290) * 8.741 (1.970) * 7.376 (2.404) * 7.447 (2.116) Childhood Obesity Rate * 5.462 * 2.155 * 0.413 * * Feel Overweight (cond: Overweight) Feel Overweight (cond: Obese) Pr. Feel Overweight (BMI 28) Pr. Feel Overweight (BMI 33) -8.870 (4.344) -6.743 (3.061) -2.736 (3.820) 1.154 (3.475) 5.299 (2.649) -14.572 (3.496) -6.389 (3.786) 3.219 (3.809) -1.193 (3.923) 2.894 (2.702) -16.54 -5.97 -16.47 -4.89 -8.69 -2.43 -3.64 -1.01 -1.08 -0.36 * * * * Women 17-74 17-25 1.826 * 8.619 * 5.211 -8.523 * -6.222 * -9.37 -1.41 (0.301) (1.823) (3.091) (3.122) 26-35 2.342 * 10.207 * 1.905 -6.325 * -3.466 * -9.25 -1.39 (0.363) (2.301) (2.406) (1.380) 36-45 1.742 * 8.501 * -0.321 -3.666 * -0.724 -5.30 -0.78 (0.442) (2.699) (1.730) (1.077) 46-55 0.931 * 3.522 -0.543 0.689 -2.96 -0.43 (0.424) (2.793) (1.475) (0.991) 56-74 1.616 * 9.763 * 1.765 1.597 -2.23 -0.35 (0.263) (1.944) (1.598) (1.082) Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. * indicates difference is significant at the 5% level. Predictions (columns 6 and 7) are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 5. Age, education, and other covariates held at sex-specific global averages. 19 Table 5. Multinomial Logit Estimates Model 1 Female NHANES 1999-2004 NHANES 1999-2004 x Female Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Underwgt. Overwgt. Underwgt. Overwgt. Underwgt. Overwgt. Underwgt. Overwgt. 0.23*** 5.38*** 0.27*** 5.10*** 0.19*** 6.66*** 0.18*** 5.84*** (0.03) (0.39) (0.04) (0.36) (0.03) (0.80) (0.03) (0.61) 2.39*** 0.72** 0.91 1.03 1.52 1.04 2.28*** 0.70** (0.52) (0.10) (0.32) (0.24) (0.54) (0.24) (0.60) (0.12) 0.76* 0.88 0.50*** 1.04 0.75* 0.88 0.86 0.90 (0.12) (0.08) (0.10) (0.12) (0.12) (0.08) (0.16) (0.11) BMI 0.58*** 1.56*** 0.58*** 1.56*** 0.58*** 1.56*** 0.57*** 1.55*** (0.01) (0.02) (0.01) (0.02) (0.01) (0.02) (0.02) (0.02) Age 17-25 1.66*** 1.10 24.00*** 0.41* 3.08*** 0.64 1.59* 1.05 (0.33) (0.14) (18.35) (0.21) (1.16) (0.18) (0.42) (0.17) 1.40* 1.13 3.81*** 0.77 1.96*** 0.86 1.40 1.08 (0.26) (0.12) (1.35) (0.18) (0.44) (0.14) (0.33) (0.16) Age 26-35 Age 46-55 Age 56-74 1.06 0.91 0.60 1.14 0.89 1.08 0.69 1.16 (0.26) (0.11) (0.19) (0.20) (0.23) (0.16) (0.17) (0.19) 1.41* 0.61*** 0.97 0.71** 1.19 0.70*** (0.28) (0.06) (0.20) (0.10) (0.28) (0.09) 0.34*** 0.68** 0.24*** 0.74* 0.34*** 0.68** 0.29*** 0.90 (0.09) (0.11) (0.06) (0.13) (0.09) (0.11) (0.12) (0.29) 0.61** 0.71** 0.44*** 0.82 0.60** 0.74** 0.57* 0.81 (0.15) (0.10) (0.12) (0.14) (0.15) (0.11) (0.18) (0.17) NHANES 1999-2004 x Age 46-55 0.5600 1.23 0.67 1.13 0.65 1.08 (0.19) (0.22) (0.23) (0.21) (0.22) (0.21) NHANES 1999-2004 x Age 56-74 0.50** 1.36** 0.46*** 1.40** 0.52** 1.36** (0.14) (0.19) (0.13) (0.20) (0.15) (0.19) 1.14 1.60*** 1.13 1.61*** 1.13 1.60*** 1.11 1.68*** (0.13) (0.12) (0.13) (0.12) (0.12) (0.12) (0.14) (0.18) 1.60*** NHANES 1999-2004 x Age 17-25 NHANES 1999-2004 x Age 26-35 High School Graduate Some College or Better Middle Income Group High Income Group Formerly Married Never Married 0.89 1.75*** 0.89 1.76*** 0.89 1.75*** 0.86 (0.09) (0.11) (0.10) (0.10) (0.10) (0.10) (0.11) (0.13) 0.87 1.38*** 0.87 1.38*** 0.87 1.38*** 0.85 1.42*** (0.09) (0.08) (0.09) (0.08) (0.09) (0.08) (0.09) (0.11) 0.60*** 1.40*** 0.60*** 1.41*** 0.59*** 1.41*** 0.59*** 1.36*** (0.07) (0.08) (0.07) (0.08) (0.07) (0.08) (0.07) (0.10) 0.90 1.30*** 0.91 1.29*** 0.90 1.29*** 0.92 1.20*** (0.10) (0.11) (0.10) (0.11) (0.10) (0.11) (0.12) (0.11) 1.11 1.13 1.10 1.13 1.10 1.13 1.26 1.05 (0.20) (0.11) (0.20) (0.11) (0.20) (0.11) (0.28) (0.13) 2.40*** 0.72* (0.61) (0.12) 1.05** 0.96** (0.03) (0.02) Mean BMI Obesity Rate Childhood Obesity Rate African American non-Hispanic Mexican American Other Race/Ethnicity 1.03 0.96 (0.07) (0.05) 0.36*** 1.48*** 0.37*** 1.49*** 0.36*** 1.48*** 0.36*** 1.48*** (0.14) (0.02) (0.14) (0.02) (0.14) (0.02) (0.17) (0.02) 1.10 0.73*** 1.09 0.74*** 1.09 0.73*** 1.06 0.77*** (0.15) (0.05) (0.15) (0.05) (0.15) (0.05) (0.17) (0.06) 1.26 0.69*** 1.25 0.69*** 1.26 0.69*** 1.36* 0.83 (0.19) (0.07) (0.19) (0.07) (0.19) (0.07) (0.23) (0.11) N 27060 27060 27060 16639 F-Statistic 87.53 86.03 83.00 86.73 Notes: Coefficients represent relative risks. Standard errors are in parentheses. *** indicates coefficient is significantly different from 1 at the 1% level or better, ** indicates coefficient is significantly different from 1 at the 5% level, * indicates coefficient is significantly different from 1 at the 10% level or better. 20 Table 6. Mean BMI and Obesity Rate by Survey and Sex Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Mean BMI NHANES III Men Women 24.042 23.923 (0.138) (0.203) 26.134 25.473 (0.151) (0.198) 27.203 26.767 (0.248) (0.354) 27.438 28.012 (0.223) (0.279) 27.356 27.621 (0.143) (0.177) 26.340 26.256 (0.111) (0.159) NHANES 1999-2004 Men Women 25.664 25.645 (0.147) (0.194) 27.394 27.815 (0.221) (0.304) 28.204 28.509 (0.195) (0.266) 28.637 28.944 (0.221) (0.319) 28.649 29.237 (0.159) (0.195) 27.713 28.059 (0.096) (0.136) Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Obesity Rates NHANES III Men Women 11.76 12.92 (1.25) (1.02) 14.88 21.35 (1.30) (1.27) 22.57 25.99 (1.34) (2.15) 23.80 32.99 (1.81) (2.03) 25.47 29.99 (1.72) (1.25) 19.16 24.13 (0.72) (0.90) NHANES 1999-2004 Men Women 22.52 22.50 (1.46) (1.27) 25.07 33.00 (1.82) (1.80) 32.45 36.43 (1.43) (1.61) 32.61 37.52 (1.63) (1.94) 34.29 41.42 (1.26) (1.50) 29.42 34.35 (0.68) (0.91) Change Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Men 1.62 6.75% 1.26 4.82% 1.00 3.68% 1.20 4.37% 1.29 4.72% 1.37 5.21% Women 1.72 7.20% 2.34 9.19% 1.74 6.51% 0.93 3.33% 1.62 5.85% 1.80 6.87% Age 17-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56-74 Total Men 10.76 91.50% 10.19 68.48% 9.88 43.77% 8.81 37.02% 8.82 34.63% 10.26 53.55% Change Women 9.58 74.15% 11.65 54.57% 10.44 40.17% 4.53 13.73% 11.43 38.11% 10.22 42.35% 21 Figure 1. Predicted Perception of Weight, Age 17-25 (Panel A:Women, Panel B: Men) Notes: Predictions are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 4. The purple lines show the thresholds for (from left to right) “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese” for 17 year olds. The dark lines show the same thresholds for individuals 21 and over (adults). See Table A.2. for details on these cutoffs. 22 Figure 2. Predicted Perception of Weight, Age 36-45 (Panel A:Women, Panel B: Men) Notes: Predictions are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 4. The dark lines show the thresholds for (from left to right) “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese” for individuals 21 and over (adults). See Table A.2. for details on these cutoffs. 23 Figure 3. Predicted Perception of Weight, Age 56-74 (Panel A:Women, Panel B: Men) Notes: Predictions are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 4. The dark lines show the thresholds for (from left to right) “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese” for individuals 21 and over (adults). See Table A.2. for details on these cutoffs. 24 Figure 4. Predicted Perception of Weight, NHANES III (A:Women, B: Men) Notes: Predictions are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 4. The dark lines show the thresholds for (from left to right) “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese” for individuals 21 and over (adults). See Table A.2. for details on these cutoffs. 25 Figure 5. Predicted Perception of Weight, NHANES 1999-2004 (A:Women, B: Men) Notes: Predictions are based on estimates of Model 1 in Table 4. The dark lines show the thresholds for (from left to right) “normal weight”, “overweight”, and “obese” for individuals 21 and over (adults). See Table A.2. for details on these cutoffs. 26 Data Appendix Data Sets The empirical analysis is conducted using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a nationally-representative series of cross-sectional studies conducted by the Centers for Disease Control. The NHANES data include observations of weight, height, and weight perception, as well as information about demographic and socioeconomic characteristics collected via in-person interviews. We examine data from NHANES III (1988--1994) and NHANES 1999--2004.14 We restrict the samples to individuals 17 to 74 years of age. We calculate individual BMI values, as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, using weight and height data measured by NHANES surveyors at mobile examination centers around the country.15 Measures Education Educational attainment is measured through self-reports of years of education, top-coded at 17+ years in the first three waves, where 16 years is an (imperfect) threshold indicating college completion. The 1999--2004 data are top-coded at 13, however, such that those with just some college cannot be distinguished from those with a college degree or better. In order to compare education effects across NHANES III and 1999--2004, we create consistent education categories, defined as 0--11 years or “less than high school,’ 12 years exactly or “high school,” and 13 or more years or “some college (or above).” Income NHANES collects self-reported data on household income, rather than individual income, as a categorical variable. NHANES also includes a related variable based on household income, the “poverty income ratio,” which is recommended for comparing income effects across different surveys.16 As recommended in the NHANES analytical guidelines, we collapse the poverty income ratio into three categories, “low,” “middle,” and “high,” representing, respectively, individuals with household income up to 1.3 times the poverty threshold, between 1.3 and 3.5 times the threshold, and more than 3.5 times the threshold.17 14 Since 1999, the survey has been conducted annually, with statistics reported in two-year increments. Reported figures for NHANES 1999--2004 refer to the combined data, but figures can be broken out for 1999--2000, 2001--2002 and 2003--2004. Data are available from NHANES 2005-2006, but we limit our analysis to the 1999-2004 data in order to enable the most comprehensive set of control variables. 15 Individuals were also asked (in an interview session conducted separately from and prior to the examination) to report their own weight and height. For some individuals, the data contain only these selfreports and not also direct measurements, but we exclude the latter from our analysis. This exclusion minimizes measurement error and does not affect representativeness, since survey weights are provided that pertain to use of the examination-only sample. 16 The poverty income ratio is roughly standardized for inflation and takes into account household size, whereas the raw income categories are not easy to align consistently in real terms across surveys. 17 Individuals with incomes up to 1.3 times the poverty line are eligible for food assistance programs and thus we might expect categorical differences in outcomes across this divide. 27 Marital Status We observe information pertaining to marital status and living situation, including whether individuals are co-habiting with a partner and whether individuals are separated in addition to the standard legal categories. Using this information we create three categories, “married,” which includes married people living with a spouse as well as unmarried individuals co-habiting with a partner, “formerly married,” which includes divorced individuals as well as separated (or married but estranged) individuals no longer living with a spouse, and “never married,” which includes those who have never been married and are not currently co-habiting. Race and Ethnicity NHANES III uses four race categories: white (non-Hispanic), black or African-American (non-Hispanic), Mexican-American, and “other.” In NHANES 1999-2004, an additional category, “other Hispanic,” was added, to capture non-Mexican Hispanics. To make the categories comparable across surveys, we merge “other Hispanic” with “other.” In the analysis, we include dummy variables for each race category, letting whites be the omitted category. Childhood obesity rates We define overweight and obesity for those under age 21 using the CDC’s official BMIfor-age-and-gender reference distributions. We adopt the convention that children and adolescents with BMI values between the 85th to 95th percentile thresholds in the reference distribution are “overweight,” and those above the 95th percentile are “obese.” Underweight children and adolescents are those below the 5th percentile, and the normal range is between the 5th and 85th percentile values. It is important to note that some sources adopt the convention that the children and adolescents between the 85th and 95th percentile BMI values are defined as “at risk of overweight,” rather than “overweight,” and that those above the 95th percentile are “overweight” rather than “obese.” For individuals ages 17-42 in NHANES III, and those ages 17-52 in NHANES 1999-2004, we estimate the childhood obesity rate (among children ages 6-11 of the same sex) that would have prevailed when they themselves were between the ages of 6 and 11. Observing the individual’s age and the time period during which she was surveyed, we can back out the approximate time frame during which she would have been a child. Then we look up the previously published childhood obesity rates (gender-specific) observed in the NHES 2 survey, conducted in 1963-1965, and in waves I through III of NHANES, covering the periods 1971-1974, 1976-1980, and 1988-1994, respectively, (Ogden, et al 2006; Ogden, et al 2002), and assign the rate from the appropriate time period. However, the year in which a given individual was surveyed is observed only up to a three year window for NHANES III subjects, and up to a 2-year window for the 1999-2004 subjects. Therefore, in some cases, we cannot determine with certainty the appropriate survey from which to draw the childhood obesity rate, and in some cases subjects would have been children during a time frame for which no survey was conducted. When either of two surveys might have been correct, we assign the average of the rates from those two surveys. In some cases, we could not map backward to an appropriate obesity rate. For example, we would need childhood obesity rates predating 1963 in order to assign 28 childhood obesity rates to individuals ages 43 and older in NHANES III and those 53 and older in the 1999-2004 survey. Also, 23 year olds observed in NHANES 1999-2000, 26 year olds observed in NHANES 2001-2002, and 28 year olds observed in NHANES 20032004 could not be assigned childhood obesity rates, and instead they were assigned the rates of 24, 27, and 29 year olds observed during the same survey periods, respectively. 29 Appendix Tables Table A.1. Measures and Basic Descriptives Men Variable NHANES 1999-2004 BMI AGE 17-25 AGE 26-35 AGE 46-55 AGE 56-74 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 17-25 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 26-35 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 46-55 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 56-74 High School Graduate Some College or Better Middle Income Group High Income Group Previously Married Never Married Obs 14545 14359 14545 14545 14545 14545 14545 14545 14545 14545 14481 14481 13298 13298 14332 14332 Mean 0.530 27.144 0.186 0.223 0.169 0.198 0.095 0.106 0.105 0.103 0.286 0.473 0.297 0.417 0.653 0.098 Std. Dev. 0.499 5.328 0.389 0.416 0.375 0.399 0.294 0.308 0.306 0.304 0.452 0.499 0.457 0.493 0.476 0.297 Min 0 13.8 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Max 1 70.2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Women Variable NHANES 1999-2004 BMI AGE 17-25 AGE 26-35 AGE 46-55 AGE 56-74 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 17-25 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 26-35 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 46-55 NHANES 1999-2004 x AGE 56-74 High School Graduate Some College or Better Middle Income Group High Income Group Previously Married Never Married Obs 16123 15893 16123 16123 16123 16123 16123 16123 16123 16123 16071 16071 14633 14633 15860 15860 Mean 0.528 27.266 0.180 0.214 0.169 0.217 0.094 0.103 0.105 0.113 0.310 0.464 0.286 0.375 0.604 0.198 Std. Dev. 0.499 6.842 0.384 0.410 0.375 0.412 0.291 0.304 0.306 0.316 0.463 0.499 0.452 0.484 0.489 0.399 Min 0 11.7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Max 1 79.6 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 30 Table A.2. BMI Cutoffs 16 17 18 19 20 Adult BMI Cutoffs for Women Under (<) Over (>=) Obese (>=) 16.8 24.6 28.8 17.2 25.2 29.6 17.6 25.6 30.4 17.8 26.2 31.0 17.8 26.4 31.4 18.5 25.0 30.0 16 17 18 19 20 Adult BMI Cutoffs for Men Under (<) Over (>=) 17.2 24.2 17.8 25.0 18.4 25.6 18.8 26.4 19.2 27.0 18.5 25.0 Obese (>=) 27.6 28.2 29.0 29.8 30.6 30.0 Notes: From CDC’s reference distributions. At a given gender and age, underweight is defined as below the 5th percentile of the relevant BMI distribution, between 5th and 85th is defined as normal, 85th to 95th is considered overweight but not obese, and 95th and above is obese. 31