MPTC_Planck

advertisement

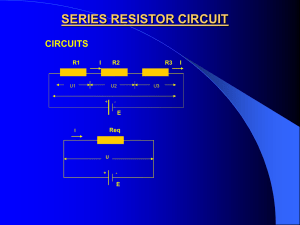

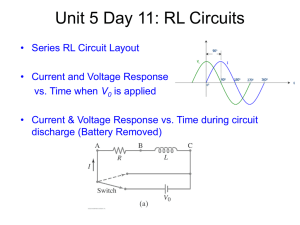

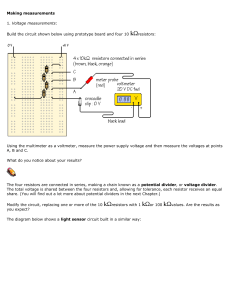

MPTC Planck’s Constant Introduction The Planck constant (denoted h) is a physical constant that governs the size of effects due to quantum mechanics. The constant was first described by Max Planck in his study of the relationship between the colors of hot objects and their temperature. According to classical physics, the distribution of frequencies of light (colors) emitted and absorbed made no sense. The higher the frequency, the more energy was predicted to be emitted and absorbed by a hot object – this was called the ultraviolet catastrophe, because there is no limit to the size of a frequency. Planck proposed that energy is actually emitted and absorbed in discrete packets, or quanta, and with that derived the correct distribution of frequencies in hot objects. In doing so he began the field of Quantum Mechanics. Soon afterward Einstein proposed that these quanta of energy were actual particles, called photons, which he used to explain the details of the photoelectric effect, whereby light absorbed by some metals can impart enough energy to release electrons from the metal; one photon is absorbed by one electron. Planck’s constant is the proportionality constant between the energy of a photon and the frequency of its associated electromagnetic wave. This idea was eventually generalized to all particles in nature, not only photons, through another relationship involving the Planck constant, between the linear momentum of a particle and its de Broglie wavelength λ. The purpose of this lab is to determine experimentally the effect of the frequency of light (independent variable) on the energy required to produce the light (dependent variable). You will do this by using a Light Emitting Diode (L.E.D) in a kind of reversal of the Photoelectric Effect – an electron losing energy will generate a photon of light. This will enable you to estimate the value of Planck’s constant. Apparatus: Materials: Infrared L.E.D. Red L.E.D. Yellow L.E.D. Green L.E.D. Blue L.E.D. UV L.E.D. Bread board Digital multimeter (used as an ammeter) 0-3.0V analog voltmeter (with 0.1 V increments) Jumper wires Alligator clip lead wires Banana plug lead wires 150 ohm resistors 220 ohm resistors Low voltage power supply L.E.D. information: L.E.D.’s are directional circuit elements. This means that current can only flow through them in one direction. The longer lead wire on the L.E.D. is the positive lead. When the potential difference across an L.E.D. is large enough an electron is boosted up into the conduction band allowing current to flow. When an electron is boosted into the conduction band it leaves a “hole” in a valence electron orbital into which an electron can fall emitting a photon. L.E.D.’s are sensitive circuit elements if too much current flows through them or too large a potential difference is placed across them they will fail. To keep the current and voltage within limits and the L.E.D. from failing a limiting resistance is generally placed in series with the L.E.D. The table below shows the characteristics of the L.E.D.’s available for this lab. The limiting resistance should be smaller than the typical resistance shown but must be slightly larger than the minimum resistance shown. color Infrared Red yellow green blue UV wavelength (nm) 940 660 587 565 430 395 Typical voltage (V) 1.2 1.7 2.1 2.1 3.2 3.2 Typical current (A) 0.05 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 Typical resistance (ohms) 96 215 195 195 140 140 Maximum Voltage (V) 1.6 2.4 3 2.80 3.8 3.8 Maximum Current (A) 0.10 0.028 0.03 0.03 0.024 0.024 Minimum Resistance (ohms) 44.0 127.5 100.0 106.7 92.6 92.6 Preliminary Procedure (For each color of L.E.D., due on lab day prior to the start of lab) 1. Show a sample calculation for a limiting resistance using only a combination of 150 ohm and/or 220 ohm resistors in series and/or parallel combinations that results in a limiting resistance slightly smaller than the listed typical resistance, but larger than the minimum resistance. 2. Draw the combination of resistors between points A and B in the circuit (see apparatus circuit diagram) that will be used as the limiting resistance. Procedure (for each color of L.E.D.) 1. Using the breadboard, jumper wires and wire leads, connect the circuit as shown in your first circuit diagram. The digital multimeter will be used as an ammeter, and should use the smaller (200 m connection). Have the teacher check at least your first circuit before continuing. 2. Set the multimeter knob on the 200 mA setting. 3. Turn the knob on the low voltage power supply counter clockwise until just before it clicks. Once it is plugged in it will now be on, but set at zero volts/amps. 4. Plug in the low voltage power supply. It may be left plugged in for the remainder of the lab. 5. Turn the knob on the power supply clockwise slowly until the current reading on the multimeter is 0.1 - 0.2 mA. Record the current and voltage reading. Note: Initially as the knob on the power supply is turned clockwise the voltage across the L.E.D. will increase with very little or no change in the current through the L.E.D. 6. Continue turning the knob on the power supply clockwise stopping to record the potential difference and current through the L.E.D. every 0.1 - 0.2 mA, until a small change in potential of only 0.1 - 0.2 V results in a several tenths of a mA change in the current. 7. Continue turning the knob on the power supply clockwise, but now stop to record the potential difference and current through the L.E.D. every 0.05 - 0.1 V. 8. Stop turning the power supply knob clockwise when the potential across the L.E.D. or the current through the L.E.D. approaches the maximum value listed in the L.E.D. table or when the power supply knob can no longer be turned clockwise any further. 9. Repeat the procedure for each color of L.E.D. Analysis 1. For each L.E.D. draw a characteristic graph as shown in the example below. Graph current (I/mA) VS. potential difference (V/V). After plotting each point extrapolate the portion of the graph that appears linear by drawing a straight best fit line through these data points to determine the minimum voltage V0 for each L.E.D. from the x – intercept. Use a separate coordinate axis system for each graph, and do not forget about uncertainty! (10 marks) 2. Show a sample calculation for the frequency of one of the L.E.D.’s. (3 marks) 3. Record the color, wavelength, frequency, and characteristic voltage for each of the L.E.D.’s in a single table. (6 marks) 4. Graph the minimum voltage V0 against the frequency of the light emitted by each L.E.D., and do not forget about uncertainty. (7 marks) 5. Calculate the slope of the line from the minimum voltage V0 against the frequency graph. (5 marks) 6. Compare the slope value from the minimum voltage V0 against the frequency graph to a standard value for Planck’s constant (in eVs). Be sure to cite the source of the value you use for Planck’s constant. (3 marks) Discussion Questions Comment on the value you arrived at for Planck’s constant, as compared to the standard value with reference to uncertainty, errors or limitations in the data or calculations. (2 marks) Why it is reasonable to compare the slope from the minimum voltage V0 against the frequency graph to Planck’s constant in eVs, even though the units for the slope of the graph are in V.s? (2 marks) Appendix USING BREADBOARDS General description: A breadboard is device that allows for simple assembly and disassembly of a circuit without the need for large numbers of connecting wires or soldering. In the image there is a single strip of conducting metal under holes A1, B1, C1, D1, and E1. This means that if the wires at the ends of two resistors are pushed into any two of the holes listed above those two ends will be connected by a conducting path. The same can be said for holes A2-E2, A3-E3, etc. as well as holes F1-J1, F2-J2, etc. The row of holes down the entire long side, on both sides with a plus at either end are connected by a conducting strip as well as those with a minus at both ends down the length on both sides. Any of the holes that are not connected such as those on rows 2 and 10 could be connected by attaching a jumper wire from anywhere on one row to anywhere on the other row. The image below shows the section of the breadboard for the first five rows (the right hand end of the image above, but rotated ninety degrees. The resistors shown on the board are connected in series. The top left resistor is connected from +1 to B1, the right side resistor is connected from E1 to E5 and the bottom left resistor is connected from -5 to C5. Connecting the positive side of a battery to anywhere on the + line and the negative side to anywhere on the negative line would create a complete circuit with current flowing clockwise around the circuit. The two ends of an appropriate meter could also be connected to the + and – row to measure the voltage across, the current through, or the resistance of the set of resistors. Note that connecting any element between any two of the points A1, B1, C1, D1, E1. or A2-E2, or F1-J1, etc would short circuit that element (so don’t do this). The image below also shows the section of the breadboard for the first five rows. The resistors on the left side connected from B1 to B5, C1 to C5, and D1to D5 are connected in parallel. To measure the voltage drop for each of the resistors, the current supplied to them, or their total (equivalent) resistance the ends of the appropriate meter could be attached to A1 and A5. Note that the resistor connected from G1 to G5 is not electrically connected to any of the other resistors since there is no direct connection between A-E and F-J. A jumper wire could be connected between E1 and F1 and E5 and F5 to bridge this gap and connect the rightmost resistor to the other three. In the image below the jumper wires connecting E1 to F1 and E5 to F5 connect the resistor on the G row to the rest of the circuit (in parallel with the D row resistor).