Microsoft Word - Ontological arguments historicalx

advertisement

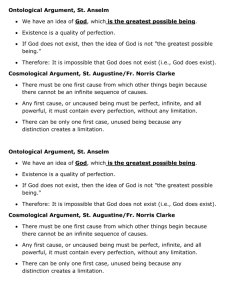

© Michael Lacewing Historical ontological arguments Ontological arguments claim that we can deduce the existence of God from the concept of God. (The word ‘ontological’ comes from ontology, the study of (Greek, -ology) of what exists or ‘being’ (ont-).)Just from thinking about what God is, we can conclude that God must exist. Because it doesn’t depend on experience in any way, the ontological argument is a priori. (An a priori argument is one whose premises are all a priori.) Anselm, Proslogium, Chs 2-4 The idea of God as the most perfect possible being has a long history. And perfection has also been connected to reality: what is perfect is more real than what is not. Anselm’s argument makes use of both these ideas. In Ch. 2, Anselm starts from the concept of God as a being ‘greater than which cannot be conceived’. Why define God like this? If we could think of something that was greater than the being we call God, then surely this greater thing would in fact be God. But this is nonsense – God being greater than God. The first being isn’t God at all. We cannot conceive of anything being greater than God – if we think we can, we’re not thinking of God. Anselm then argues that if we think of two beings, one that exists and one that doesn’t, the one that actually exists is greater – being real is greater than being fictional! So if God didn’t exist, we could think of a greater being than God. But we’ve said that’s impossible; so God exists. 1 2 3 4 By definition, God is a being greater than which cannot be conceived. (We can coherently conceive of such a being, i.e. the concept is coherent.) It is greater to exist in reality than to exist only in the mind. Therefore, God must exist. In Ch. 3, Anselm adds premise (2) and explains premise (3) further. Conceive of two almost identical beings, X and Y. However, X is a being which we can conceive not to exist; X’s not existing is conceivable. By contrast, Y’s not existing is inconceivable. We can conceive of such a being, a being who must exist. Clearly, Y is a greater being than X. Therefore, the greatest conceivable being is a being who, we conceive, must exist. It is inconceivable that the greatest conceivable being does not exist. Of course, it can seem like we can think ‘God does not exist’. In Ch. 4, Anselm notes that we can have this thought, we can think this string of words. But, he argues, in having this thought, we fail to understand the concept of God fully. Once we fully understand the concept, we can no longer affirm the thought because we recognise that it is incoherent. Gaunilo’s objection Anselm received an immediate reply from a monk named Gaunilo. Gaunilo raises several objections, of which the most famous appears in §§5–7 (appendix to St Anselm’s Proslogium (from In Behalf of the Fool)). The essence of the objection is that the conclusion doesn’t follow from the premises. How great is the greatest conceivable being? Well, if it doesn’t exist, it is not great at all – not as great as any real object (§5)! We can conceive how great this being would be if it existed, but that doesn’t show that it is as great as all that and so must exist. Suppose we even grant that the non-existence of God is inconceivable (§7). This still doesn’t show that God actually exists. First, we need to establish that God does exist. And then from understanding his nature, we can infer that he must exist. Gaunilo argues that Anselm’s inference must be flawed because you could prove anything which is ‘more excellent’ must exist by this argument (§6). I can conceive of an island that is greater than any other island. And so such an island must exist, because it would be less great if it didn’t. This is ridiculous, so the ontological argument must be flawed. Anselm’s reply (Apologetic) Gaunilo slips from talking about the greatest conceivable being to talking about conceiving of a being that is greater than all other beings. So he talks of an island that is greater than other islands. But this doesn’t work. It is possible to conceive of the being which, as it happens, is greater than all other beings as not existing. So let’s correct Gaunilo here, and talk of ‘the island greater than which is inconceivable’. Anselm claims that the ontological argument works only for God, and so this is not a counterexample. Why? Anselm’s reasoning is to show that there is something incoherent in thinking that the greatest conceivable being doesn’t exist. By contrast, the thought that the greatest conceivable island doesn’t exist is coherent. When we have this thought, we are still thinking of an island. There is nothing in the concept of such an island that makes it essentially or necessarily the greatest conceivable island. Compare: an island must be a body of land surrounded by water. An island attached to land is inconceivable. But islands aren’t essentially great or not. Instead, the thought of an island that is essentially the greatest conceivable island is itself somewhat incoherent. For example, what would make it the greatest? By contrast, God, argues Anselm, must be the greatest conceivable being – God wouldn’t be God if there was some being even greater than God. So being the greatest conceivable being is an essential property of God. But then because it is greater to exist in reality than merely in the mind, if we think of God as not existing in reality, we aren’t thinking of God at all. So to be the greatest conceivable being, God must exist. We may object, however, that even if Anselm is right about the island, Gaunilo’s objection is correct: we must first demonstrate that God exists before we can say that God is, rather than is merely conceived to be, the greatest conceivable being. Descartes, Meditation V Descartes’ version of the ontological argument talks about God being supremely perfect, rather than ‘a being greater than which cannot be conceived’, and it relies on his theory of clear and distinct ideas. The argument itself is very brief: The idea of God (that is, of a supremely perfect being) is certainly one that I find within me…; and I understand from this idea that it belongs to God’s nature that he always exists. (p. 24) Once Descartes adds that existence is a perfection, his argument becomes this: 1 2 3 4 5 I have the idea of God. The idea of God is the idea of a supremely perfect being. A supremely perfect being does not lack any perfection. Existence is a perfection. Therefore, God exists. Descartes accepts that it is easy to believe that God can be thought of as not existing. But careful reflection reveals that this is a self-contradiction. A different case helps clarify the point: you may think that there can be triangles whose internal angles don’t add up to 180 degrees, but reflection proves this impossible. Descartes begins Meditation V by commenting on this fact: our thought is constrained in this way. The ideas we have determine certain truths, at least when our ideas are clear and distinct. Once you make the idea of a triangle clear and distinct, you understand that its internal angles add up to 180 degrees, and this shows that this is, in fact, true. We can apply this to God. Careful reflection on the concept of God reveals that to think that God does not exist is a contradiction in terms, because it is to think that a supremely perfect being lacks a perfection (existence). Thus, we can know that it is true that God exists. In fact, it shows that God must exist. A contradiction in terms does not just happen to be false, it must be false. So to say ‘God does not exist’ must be false; so ‘God exists’ must be true. As in the case of the triangle, it is not our thinking it that makes the claim (that God exists) true. Just as the concept of a triangle forces me to acknowledge that its internal angles add up to 180 degrees, so the concept of God forces me to acknowledge that God exists. Furthermore, I cannot simply change the concept in either case; I can’t decide that triangles will have two sides nor that God is not a supremely perfect being. I haven’t invented the concept of God, such that it includes existence. I discover it. God is the only concept that supports this inference to existence, because only the concept of God (as supremely perfect) includes the concept of existence (as a perfection). We can’t infer the existence of anything else this way. Hume’s objection (Dialogues concerning Natural Religion, Pt 9, p. 39) Both Anselm and Descartes have argued that it is self-contradictory to say that God does not exist. Hume claims that this is simply not true: 1 2 3 Nothing that is distinctly conceivable implies a contradiction. Whatever we conceive as existent, we can also conceive as non-existent. Therefore, there is no being whose non-existence implies a contradiction. In this argument, Hume is drawing on his analysis of knowledge. To say that ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction entails that ‘God exists’ is a relation of ideas. But this can’t be right, because claims about what exists are matters of fact. Put another way, if ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction, then ‘God exists’ must be analytic. But claims about what exists are synthetic. Descartes could respond in either of two ways. He could claim that ‘God exists’ is a synthetic truth, but one that can be known by a priori reflection. Or he could claim that ‘God exists’ is an analytic truth, though not an obvious one. Because he doesn’t have the concepts ‘analytic’ and ‘synthetic’, he doesn’t, of course, say either. Instead, (in an appendix to the Meditations) he argues that Hume’s premise (2) is false. Because our minds are finite, we normally think of the divine attributes – omnipotence, omniscience, existence, etc. – separately and so we don’t notice that they entail one another. But if we reflect carefully, we shall discover that we cannot conceive of any one of the other attributes while excluding necessary existence. For example, in order for God to be omnipotent, God must not depend on anything else, and so must not depend on anything else to exist. However, this response faces Gaunilo’s objection to Anselm: God’s attributes only entail each other if God actually exists. Of course, if God doesn’t exist, then God isn’t omnipotent (or anything else), so God’s omnipotence doesn’t entail his existence. Leibniz’s supplement Leibniz admired Descartes’ argument, but thought that it was incomplete (New Essays on Human Understanding, Bk 4, Ch. 10, p. 219). Descartes assumes that the concept of God is coherent, that a supremely perfect being is possible. Leibniz is right that, for any ontological argument to be valid, this premise is needed. But is it true? Leibniz claims that a better understanding of what a ‘perfection’ is will solve the matter (‘That a Most Perfect Being Exists’). He defines a perfection as a ‘simple quality which is positive and absolute, or, which expresses without any limits whatever it does express’. So, for example, ‘power’ is a perfection. It is unanalysable, positive, and expresses the idea of power without placing limits on power. (Compare ‘horsepower’, which originally expressed the idea of the power of a horse, which is limited.) Leibniz then argues, in a very abstract piece of reasoning, that because all perfections are simple and positive, it can’t be shown that they are incompatible. Nothing about any one perfection places a restriction on any other perfection. It is possible, therefore, that they are compatible, and so that they can all coexist in one being. So a supremely perfect being is possible. We can object that Leibniz’s concept of a perfection is unclear and possibly false. What makes a quality ‘positive’ rather than ‘negative’? And are any qualities ‘simple’ in the way Leibniz imagines? Our discussion of the attributes of God shows that the matter is complicated. It is doubtful that there is any general proof that the concept of God is coherent; we must take each attribute in turn. Kant, ‘On The Impossibility of an Ontological Proof of the Existence of God’ Kant presents what many philosophers consider to be the most powerful objection to any ontological argument (Critique of Pure Reason, Second Division (Transcendental Dialectic), Bk 2, Ch. 3, §4). It is a development and explanation of Hume’s objection. Ontological arguments misunderstand what existence is, or what it is to say that something exists. Premise (3) of Anselm’s argument and premise (4) of Descartes’ are both false. Things don’t ‘have’ existence in the same way that they ‘have’ other properties. So existence can’t be a perfection or make something ‘greater’. Consider whether ‘God exists’ is an analytic or synthetic judgement. In claiming that ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction, it seems that Anselm, Descartes and Leibniz take ‘God exists’ to be an analytic judgement. Now, an analytic judgement unpacks a concept. The concept of the predicate, ‘three sides’, is part of the concept of the subject, ‘triangle’. And so the analytic truth ‘A triangle has three sides’ unpacks the concept of a triangle and tells you something about what triangles are. However, saying ‘x exists’ does not add anything to a concept of what x is. It doesn’t tell you anything more about x. ‘Dogs exist’ doesn’t inform you about what dogs are. Put another way, ‘existence’ isn’t a real predicate. The concept of existence is not a concept that can be added into the concept of something. If I say ‘The kite is red’, I add the concept of ‘red’ onto the concept of ‘kite’, and can create the new concept of a red kite. But if I say ‘The kite exists’ or ‘The kite is’ – this adds nothing to the concept of the kite. The claim that x exists is not a claim about my concept of x, but a claim that something exists that corresponds to my concept. So the claim that x exists is a synthetic judgement, not an analytic one. But that means that it is not contradictory to deny it. This applies even in the case of God. ‘God exists’ is just ‘God is’; it doesn’t add anything to, or unpack, the concept of God. Even if we allow that God, the greatest conceivable being, is possible, that the existence of God is possible, this remains a claim about the concept, not existence. What we want to show is that we can not only coherently think about God (God is possible a priori), but that it is also possible that we actually experience him (God is possible a posteriori). But this we cannot deduce from the conceptual possibility of his existence. For example, there is no difference between the concepts of 100 real thalers (the money of Kant’s day) and 100 possible thalers. Adding the concept of something existing does not make the thalers exist. Likewise with God. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 If ‘God does not exist’ is a contradiction, then ‘God exists’ is an analytic truth. If ‘God exists’ is an analytic truth, then ‘existence’ is part of the concept of God. Existence is not a predicate, something that can be added on to another concept. Therefore, ‘God exists’ is not an analytic truth. Therefore, ‘God does not exist’ is not a contradiction. Therefore, we cannot deduce the existence of God from the concept of God. Therefore, ontological arguments cannot prove that God exists.