Completed Proposal - University of Dayton

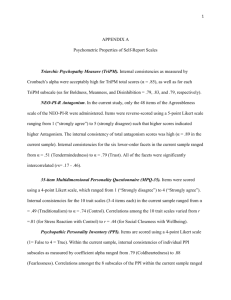

advertisement