The Engaged Learning Index: Implications for Faculty Development

advertisement

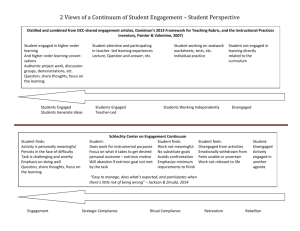

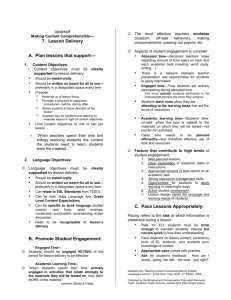

Engaged Learning 1 The Engaged Learning Index: Implications for Faculty Development Laurie A. Schreiner Azusa Pacific University Michelle C. Louis Azusa Pacific University Student engagement is a construct that has received considerable attention in higher education research because of its relationship to student learning (Carini, Kuh, & Klein, 2006; Cross, 2005), its potential connection to student persistence (Milem & Berger, 1997), and because it serves as an indicator of institutional effectiveness (Shulman, 2005). If postsecondary educators accept Shulman’s premise that “learning begins with student engagement” (p. 38), then methods for ascertaining the extent to which students are engaged in the learning process can provide helpful feedback for faculty who wish to make an impact on student learning. National surveys of faculty developers indicate that the largest programming need is for learning-centered pedagogical methods, yet Sorcinelli, Austin, Eddy, and Beach (2006) note that there are few measures to assess whether such programming efforts have successfully affected students’ engagement in learning. While broad indicators of student engagement such as the National Survey of Student Engagement are available at the institutional level, brief but reliable and valid assessments of students’ engagement in learning are not readily available to faculty. In a search of the existing literature, only one measure of learning engagement was found that was accessible to faculty (Handelsman, Briggs, Sullivan, & Towler, 2005). However, this measure assesses engagement only at the course level and its psychometric properties thus far are based on a single institution. In addition, many of the existing approaches for assessing student engagement in learning focus solely on behaviors, while most researchers agree that academic engagement is a Engaged Learning 2 multifaceted construct (Bean, 2005; Fredericks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004; Handelsman et al., 2005). The Engaged Learning Index (Schreiner & Louis, 2006) was developed to extend beyond behavioral indicators of engagement by also including psychological components in its assessment of student engagement in the learning process. The purpose of the current study is to connect what has been learned from research conducted across multiple large national samples using the Engaged Learning Index to practices that can inform the faculty development process and provide helpful, immediate feedback to faculty Conceptual Framework The advent of the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) in 2000 provided a means for assessing engagement in a more intentional and empirical way and dramatically increased the visibility of the construct of student engagement within the field of higher education. As a result, colleges and universities that use this instrument are gaining an understanding of the levels of engagement within their first-year and senior students and are provided with practical ways of supporting and encouraging such engagement. The campus reforms that have occurred because of NSSE’s visibility and the research it has spawned have been a valuable contribution to American higher education. An examination of the items and scales within NSSE (Kuh, Hyek, Carini, Ouimet, Gonyea, & Kennedy, 2001; National Survey of Student Engagement, 2007), as well as an exploration of the conceptual framework of the instrument (Kuh, 2003b), reveals that its intention is to measure “the extent to which students are engaged in empirically derived good educational practices and what they gain from their college experience” (p. 1). Although recent efforts have been made to assess student investment in deep learning (NSSE, 2005, 2007), Nelson Laird, Shoup, Kuh, and Schwartz (2008) note that “the NSSE survey was not specifically Engaged Learning 3 designed to assess certain precursors to deep approaches to learning, such as student motivation for learning” (p. 481). The focus of this instrument remains centered on measuring student behaviors indicative of engagement and the effective educational practices that support such behaviors. The intent is that these indicators of student engagement can serve as a proxy for institutional quality. The use of the term “engagement” in NSSE is synonymous with Astin’s (1984) term “involvement” in his original articulation of student involvement theory. Although Astin defines student involvement as “the amount of physical and psychological energy that the student devotes to the academic experience” (p. 298), his focus is primarily on the behaviors in which the student engages: participating in campus organizations, interacting with faculty and peers, attending campus events, and spending time studying, for instance. He articulates a deliberate choice to focus on the behavioral components of involvement rather than the motivational components, noting that “it is not so much what the individual thinks or feels, but what the individual does, how he or she behaves, that defines and identifies involvement” (p. 298). Bean (2005) has asserted that this view of involvement solely as behavior does not provide a complete picture of student engagement; while the behavioral component is necessary, it is not a sufficient definition of engagement. As he notes, “[p]articipating in events without committing psychological energy to them indicates that they are unimportant to the student and thus ineffectual in changing the student…. Behavior without thought is not likely to lead to the gains associated with engagement” (pp. 2-3). As a result of this need to expand the conceptualization of student engagement in the learning process to include psychological factors, the Engaged Learning Index (ELI, Schreiner & Louis, 2006) was developed to measure cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of Engaged Learning 4 engaged learning (Fredericks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004), drawing on multiple disciplinary perspectives to do so. Grounded in the motivational model of Ryan and Deci’s (2000) selfdetermination theory, the ELI incorporates concepts from the literature in psychology and higher education, such as flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1975), mindfulness (Langer, 1997), and deep learning (Tagg, 2003). The resulting construct of engaged learning is thus conceptualized as “a positive energy invested in one’s own learning, evidenced by meaningful processing, attention to what is happening in the moment, and involvement in learning activities” (Schreiner & Louis, p. 9). The conceptual framework upon which the Engaged Learning Index is grounded is Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory. Based on the construct of intrinsic motivation, this theory postulates that individuals whose motivation is authentic, or in Baxter-Magolda’s (1999) term, self-authored, are more interested, excited, and confident as they approach a task, which then produces higher levels of creativity and persistence within the task, as well as better performance (Sheldon, Ryan, Rawsthorne, & Ilardi, 1997). Even when controlling for preexisting levels of self-efficacy, these persons experience greater success, “heightened vitality” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 69), and an enhanced sense of well-being. Self-determination theory captures the motivational impetus for engagement that has been missing from behavioral models, such as those represented by Astin’s (1984) involvement theory. The cognitive and affective elements of engagement that have been incorporated into the model of engaged learning in this study derive from Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) concept of flow and Langer’s (1997) articulation of mindfulness. Flow is often described as an energized, alert mental state when one becomes immersed in challenging activities that are of interest. This heightened attention and energy level result when a person is optimally challenged, that is, when the task presents an opportunity for a person to stretch beyond his or her current performance but Engaged Learning 5 not beyond one’s capability (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Langer’s (1997) construct of mindfulness adds another dimension to engagement with its emphasis on psychological presence in the current moment and its focus on novel distinctions. Mindful learning occurs when students notice what is new or different in the surrounding environment or in the task at hand. This novelty captures their attention as they attempt to distinguish the new from what they already know. In Langer’s description of mindfulness, there is a sense of active involvement, high curiosity, and a particular quality of attention that keeps the learner firmly situated in the present. Mindfulness also involves perspective-taking and making the material personally meaningful, both of which lead to the deep learning (Tagg, 2003) that tends to have the most significant and lasting impact on students’ lives. Deep learning (Biggs, 1987, 2003; Tagg, 2003) has been described as an approach to the learning process which focuses on meaning making. In contrast to a surface approach which relies on rote memorization and focuses on earning a grade or passing a test in order to avoid failure, deep approaches to learning encourage students to make connections and formulate personal meaning in the learning process. Making connections to previous learning, to learning in other courses, and to aspects of students’ personal lives promotes significant learning that lasts beyond an individual course. Evidence of such learning can be seen in students’ use of strategies such as discussing ideas with others, asking questions for deeper understanding, applying knowledge to real-world situations, and integrating concepts with prior learning. In creating the Engaged Learning Index we also acknowledge that behaviors can be an indication of students’ psychological engagement in an activity. Thus, Astin’s (1984) concept of involvement is represented in the instrument by items that focus on active participation in class discussions and in asking questions of professors during class. The resulting multifaceted Engaged Learning 6 construct of engaged learning encompasses both the physical and psychological energy to which Astin (1984) originally referred in his articulation of student involvement. Methods Data Sources and Sample The purpose of the present study is to connect what has been learned from the research conducted on the Engaged Learning Index (ELI; Schreiner & Louis, 2006) across multiple undergraduate student samples to implications for how faculty development programs might encourage and measure the effects of teaching practices that facilitate engaged learning. In the spring of 2007 the ELI was administered to 2,258 undergraduate students representing the full range of class levels at 13 different public and private colleges and universities across the United States. Responses were collected via online surveys administered to students through a contact on each campus, after the institutional review board on the campus approved the study. Each campus utilized their own method of sampling students via e-mail contacts. Incentives were provided in the form of a lottery drawing for $25 Starbucks gift cards. After deleting part-time students and those cases with missing values or multivariate outliers, the final sample contained 1,747 full-time undergraduate students. As can be seen in Table 1, 71.9% of the students in this final sample were women. The sample included 22% firstgeneration students and 75.4% of the sample was Caucasian. Almost two-thirds of the sample lived on campus. Approximately three-fourths intended to pursue an advanced degree at some point in their lives; slightly less than one-fourth had transferred into the institution they were currently attending. Engaged Learning Table 1 Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 1,747) Characteristic Gender Female Male Class First year Sophomore Junior Senior Generation First generation Not first generation Degree Aspirations Bachelors Teaching credential Masters Doctorate Medical or law Institution was first choice at enrollment Yes No Housing On-campus Off-campus Race/Ethnicity African-American American Indian/Alaska Native Asian American/Pacific Islander Caucasian Hispanic Multiethnic Prefer not to respond Institutional Control Public Private n % 1256 491 71.9 28.1 454 494 387 412 26.0 28.3 22.1 23.6 384 1363 22 78 349 86 886 280 146 20.0 4.9 50.7 16.0 8.3 1218 529 69.7 31.3 605 1142 34.6 65.4 74 11 105 1317 123 53 64 4.2 .6 6.0 75.4 7.0 3.0 3.8 819 928 46.9 53.1 7 Engaged Learning 8 Measures The Engaged Learning Index is a 10-item instrument that measures affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of an individual student’s level of engagement in the learning process across all academic courses. Each item is expressed as a positive or negative statement to which the student responds on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The items are located temporally within the student’s recent experiences. The instructions for the instrument can be varied to direct students’ attention to one particular course or to all the courses in which they are enrolled throughout the term. The affective items on the ELI include feeling energized by learning, feeling that the learning experience is worthwhile, and feeling bored in class. The behavioral components include discussing what is being learned with other students outside of class, participating in class discussions, and asking questions in class. The cognitive components include being interested and paying attention, applying the course material to other aspects of one’s life, connecting the material to previous learning, and experiencing one’s mind wandering. Negative items are reverse-scored and are scattered throughout the instrument in order to prevent response sets. In an earlier pilot study of the psychometric properties of the ELI, an exploratory principal components analysis using varimax rotation found that three components with eigenvalues over 1.0 accounted for 69.19% of the total variance. These components were labeled Meaningful Processing (accounting for 43.21% of the variance), Focused Attention (accounting for 14.86% of the variance), and Active Participation (accounting for 11.12% of the variance). Reliability, as measured by coefficient alpha, has been estimated as α = .85, with scale alpha coefficients ranging from .73 (Active Participation) to .84 (Meaningful Processing). Engaged Learning 9 In addition to the ELI items, each participant responded to a variety of items indicative of desired outcomes of the postsecondary educational experience, such as satisfaction with learning, academic performance, satisfaction with the college experience, satisfaction with the quality of interaction with faculty, frequency of interaction with faculty outside of class, and self-reported learning gains in critical thinking skills. These outcomes were utilized as dependent variables in the current study, with separate regression equations conducted for each. The variables are outlined in Table 2, along with their corresponding response scales and coding strategies. Engaged Learning 10 Table 2 Description of Variables Dependent Variables: College Grades Self-reported variable with response options on a 6-point scale where 1=mostly A’s 2= A’s and B’s 3=mostly B’s, 4= B’s and C’s 5=mostly C’s 6=below a C average. Reverse scored. Critical Thinking Gains Response to the item: “Compared to when you first started college, how much do you think you have changed in your critical thinking skills?” Measured with 6-point scale, 1=no change at all, 6=quite a lot of change. Learning Satisfaction Response to the item: “Rate your satisfaction with the amount you are learning in college.” Measured with a 6-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 6=very satisfied. Faculty Satisfaction Response to the item: “Rate your satisfaction with the amount of contact you have had with faculty this year.” Measured with a 6-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 6=very satisfied. Faculty Interaction Response to the item: “How often do you interact with faculty outside of class?” Measured with a 4-point scale, 1=never, 4=frequently. Total Satisfaction Response to the item: “Rate your overall satisfaction with your college experience so far.” Measured with a 6-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 6=very satisfied. Background Variables First-generation Definition First in immediate family to attend college=1; not first to attend college=2 Race/ethnicity Dummy variable coded 1=white; 0=all other ethnicities. Gender Female=1, male=2 Degree Aspirations Dummy variable. Plan to attain an advanced degree at any point in life, coded 0=no, 1=yes. Residence Live on campus, coded 0=no, 1=yes. Level Year in postsecondary education, coded 1 = first-year, 2 = sophomore, 3 = junior, 4 = senior. Institutional Control Dummy variable coded 0=no, 1=yes for public universities. Independent Variables Definition Meaningful Processing Sum of five items from the Engaged Learning Index: (1) I often discuss with my friends what I am learning in class; (2) I feel as though I am learning things in my classes that are worthwhile to me as a person; (3) I can usually find ways of Engaged Learning 11 applying what I’m learning in class to something else in my life; (4) I find myself thinking about what I’m learning in class even when I’m not in class; (5) I feel energized by the ideas that I am learning in most of my classes. Each item is measured on a 6-point scale: 1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree. (α = .84) Focused Attention Sum of three items from the Engaged Learning Index: (1) It’s hard to pay attention in many of my classes; (2) In the last week, I’ve been bored in class a lot of the time; (3) Often I find my mind wandering during class. Each item is measured on a 6-point scale: 1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree. All items are reverse scored. (α = .82) Active Participation Sum of two items from the Engaged Learning Index: (1) I regularly participate in class discussions in most of my classes; (2) I ask my professors questions during class if I do not understand. Each item is measured on a 6-point scale: 1=strongly disagree, 6=strongly agree. (α = .73) Data Analysis and Results The first phase of data analysis involved a confirmatory factor analysis of the Engaged Learning Index conducted with AMOS (version 16.0), utilizing the maximum likelihood estimation procedure. An examination of the data indicated that the sample was representative of the racial balance on the campuses that had been sampled, but was disproportionately female. After deleting all cases with missing data or multivariate outliers, standardizing all variables, and weighting the sample by gender, the three-factor model derived from the exploratory principal components analysis, with engaged learning as a higher-order factor, was tested for its fit with the current sample of 1,747 undergraduate students. The quality of the model’s fit was assessed using two criteria in addition to the traditional chi-square goodness-of-fit, which was highly inflated due to the large sample size. The comparative fix index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) compares the improved fit of the hypothesized model to a null model that assumes the model’s observed variables are not correlated; this null model is also known as the independence model. CFI values can range from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating a perfect fit. Values greater than .95 are considered to represent a well-fitting model (Thompson, 2004). The second criterion for fit, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Engaged Learning 12 Browne & Cudeck, 1993), is a parsimony-adjusted index that indicates the fit between the implied and the population covariance matrix. In contrast to the CFI, lower RMSEA levels are indicative of a better fit, with values closer to 0 being more desirable. A commonly accepted standard is that RMSEA values of less than .06 represent a well-fitting model (Thompson, 2004). The CFA indicated that the three-factor model with engaged learning as a higher-order construct provided an excellent fit, with χ2 (32)= 471.91, p < .001, CFI = .98, and RMSEA = .046 with 90% confidence intervals of .042 to .049. All measured variables loaded strongly on their respective latent variables (β range = .61 to .82). The model is depicted in Figure 1. Engaged Learning 13 .38 e5 Zeli2.56 e4 Zeli4.52 e3 Zeli6.45 e2 Zeli9.55 e1 Zeli11 .61 .75 e11 .92 .72 Meaningful .67 Processing .74 .96 e12 .52 e8 Zeli5r.63 e7 Zeli8r.60 .80 .77 e6 Zeli13r .26 .72 Focused Attention Engaged Learning .51 .57 e13 .33 e10 .67 .82 Zeli3.45 .67 e9 Zeli7 Active Participation Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model of the Revised Engaged Learning Index The second phase of data analysis utilized a series of hierarchical multiple regression equations, one for each of the desired outcomes that served as dependent variables. In each case, institutional control (public or private) and student characteristics such as race, gender, firstgeneration status, residence (on or off campus), class level, and degree aspirations were entered Engaged Learning 14 in the first block of the analysis and students’ responses to each scale of the Engaged Learning Index were entered as the second block of the analysis. The variables entered in block one as control variables were chosen due to previous research that had indicated their significant relationship to at least one of the dependent variables or to student engagement (Hu & Kuh, 2002; Kuh, 2003a; Kuh, Gonyea, & Palmer, 2001; Pascarella et al., 2006; Pike & Kuh, 2005). Separate regression equations were calculated for the following criterion variables: students’ satisfaction with faculty, satisfaction with learning, satisfaction with their total college experience, frequency of interaction with faculty outside of class, self-reported gains in critical thinking skills during college, and self-reported college grades. Other researchers have found a significant relationship between students’ self-reported grades and actual grades (Olsen et el., 1998) and have routinely used self-reported learning gains as an outcome measure (Nelson Laird, et al., 2008). Table 3 outlines the means and standard deviations of the ten items in the Engaged Learning Index, while Table 4 presents the results of each of the regression equations. After controlling for institutional type and student demographic characteristics, scores on the Engaged Learning Index accounted for an additional 5% to 30% of the variance in desired outcomes. ELI scores contributed least to the variance in self-reported college grades and most to the variance in students’ learning satisfaction, satisfaction with faculty, and gains in critical thinking skills. Engaged Learning 15 Table 3 Means and Standard Deviations for Engaged Learning Index Items Item 1. I often discuss with my friends what I’m learning in class. 2. I regularly participate in class discussions in most of my classes. 3. I feel as through I am learning things in my classes that are worthwhile to me as a person. 4. It’s hard to pay attention in many of my classes. (reverse scored) 5. I can usually find ways of applying what I’m learning in class to something else in my life. 6. I ask my professors questions during class if I do not understand. 7. In the last week, I’ve been bored in class a lot of the time. (reverse scored) 8. I find myself thinking about what I’m learning in class even when I’m not in class. 9. I feel energized by the ideas that I am learning in most of my classes. 10. Often I find my mind wandering during class. Note: N = 1,747 M 4.55 4.42 4.78 SD 1.03 1.16 1.00 3.82 4.50 1.22 1.01 4.35 3.64 1.17 1.37 4.34 1.05 4.14 1.05 3.18 1.20 The Meaningful Processing Scale of the ELI was most predictive of the various criterion variables. The items on the scale appear to measure the psychological energy students invest in the learning process through thinking about material presented in class even outside of the classroom setting, believing the learning to be personally valuable, applying course material to other aspects of their lives, discussing with their friends what they are learning, and feeling energized by the ideas they are learning. This scale had the largest correlation with students’ satisfaction with the amount they are learning (r = .58; partial r = .45). In addition to its significant contribution to learning satisfaction, scores on this scale were significantly predictive of all other criterion variables as well: overall satisfaction with the college experience, gains in critical thinking skills, college grades, and both frequency and satisfaction with faculty interaction. Thus, the meaningful processing that is indicative of deep learning appears to be Engaged Learning 16 significantly associated with students’ overall perception and satisfaction with their campus experiences, as well as with the quality of their learning. The Focused Attention scale of the ELI was moderately predictive of learning satisfaction and was predictive of all other outcomes except gains in critical thinking skills and frequency of faculty interaction. The Active Participation scale contributed significantly to the variance in faculty interaction and satisfaction with faculty, as well as college grades and total satisfaction with the college experience, but was not a significant predictor of learning satisfaction or gains in critical thinking skills. Engaged Learning 17 Engaged Learning 18 Table 4 Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analyses for Variables Predicting Desired Outcomes of Postsecondary Experience ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Criterion Variables Variable Learning Satisfaction Faculty Satisfaction Faculty Interaction β β Step 1 Institutional Control -.02 Gender -.07** First generation -.01 Ethnicity -.04 Degree aspirations .07** College grades .11*** R2 .03 Step 2 Meaningful Processing .49*** Focused Attention .13*** Active Participation .00 R2 change .30 2 Total R .33 N = 1,747 * p < 05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001 College Grades Total Satisfaction β Critical Thinking Skills Gains β β β -.05* -.06** .02 .01 .05* .16*** .07 -.08*** -.06* .02 .03 .06** .12*** .07 -.03 .00 .00 .07** .05* .07** .09 -.11*** -.18*** .07** .11*** .13*** NA .10 -.01 -.03 -.03 .02 .04 .14*** .03 .26*** .06* .16*** .13 .20 .16** -.02 .21*** .08 .15 .33*** .01 .00 .10 .19 .06* .09*** .15*** .05 .15 .26*** .07** .09*** .10 .13 Engaged Learning 19 Discussion This study makes two notable contributions to the conceptualization of undergraduate student engagement in the learning process. First, it confirms that the Engaged Learning Index is a reliable and valid tool for assessing students’ psychological engagement in learning. The ELI consists of only ten items, yet is internally consistent (α = .85) with a robust factor structure containing three components of Meaningful Processing, Focused Attention, and Active Participation which account for almost 70% of the variance in engaged learning. The confirmatory factor analysis also demonstrated that engaged learning is a higher-order construct, so that total scores on the ELI can be utilized meaningfully. Second, this study demonstrates that engaged learning contributes substantially to the variation in students’ learning satisfaction, as well as their critical thinking skills, interaction and satisfaction with faculty, overall satisfaction with the college experience, and, to a lesser extent, their grades. This significant contribution is over and above the amount of variance explained by students’ demographic characteristics such as their gender, ethnicity, class level, residence, firstgeneration status, degree aspirations, or type of institution attended. When students are engaged cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally in the learning process, they are more likely to be satisfied with their learning and to report gains in their critical thinking skills. This satisfaction extends beyond the classroom, as they are also more likely to be satisfied with faculty, are more likely to interact with faculty outside of class, and express higher levels of satisfaction with their entire college experience. Implications for Faculty Development The concept of engaged learning as measured in the ELI offers additional insights into student success that are worth exploring further with faculty in the context of faculty Engaged Learning 20 development programs. There are four implications for faculty development in particular that arise from these findings. Measuring engaged learning. The first implication is that the methods often used to assess students’ engagement in the learning process have not provided a complete picture, as much of what constitutes engaged learning is not directly observable in student behavior. Faculty typically rely on observable behaviors as indicators of engagement and may make judgments about students’ learning based on the level of active participation they see in the classroom. Yet behaviors such as participating in class discussions and asking questions of professors account for little, if any, of the variation in student success outcomes. For example, for every standard deviation increase in Meaningful Processing scores, critical thinking skill gains increase by one-third of a standard deviation and learning satisfaction increases by almost half a standard deviation; yet for every standard deviation increase in Active Participation scores, there is no increase whatsoever in critical thinking skill gains or in learning satisfaction. Active Participation scores are significantly predictive of students’ interaction with faculty (β = .21), their satisfaction with faculty (β = .16), and their grades (β = .15), however. This finding may indicate that students who are behaviorally involved in learning activities are also more likely to engage in such behaviors as seeking to interact with faculty outside of class, which may increase their satisfaction with faculty and potentially even their grades. It may also indicate that deep learning and meaningful processing are not always necessary in order to earn high grades. Nelson Laird et al. (2008) found that while more frequent use of deep approaches to learning were related to higher levels of student satisfaction, personal development, and learning gains, they were not significantly related to students’ grades. Engaged Learning 21 Using an instrument such as the Engaged Learning Index could provide professors and faculty developers with more reliable and immediate feedback about students’ engagement in the learning process. Because the instructions to students can be modified to refer to either a single class or to all the courses in which they are enrolled in a given semester, the ELI can be used by individual faculty or by institutions and faculty developers as they examine the overall levels of engaged learning within various majors, class levels, and programs across the institution. For example, individual faculty can use the ELI at various times in their classes for feedback to determine the impact that the course is having on students’ engagement in the learning process. Faculty developers could also use the ELI as a pretest and posttest measure of the effectiveness of interventions they design for the improvement of learning-centered teaching. As Sorcinelli et al. (2006) note, “teaching for student-centered learning” (p. 73) has been identified by faculty developers as the most important issue to address in faculty development programs, yet there are few reliable measures for assessing the impact of such programs. Because psychological engagement is often a precursor to the learning process and leads to higher levels of learning satisfaction and critical thinking skills, helping students become emotionally engaged may be as important as teaching knowledge and skills (Handelsman et al., 2005). As faculty development programs focus more on teaching faculty to become learning facilitators who utilize a broad range of strategies, the ability to measure student engagement in learning can provide helpful feedback. Strategies for deep learning. The second implication for faculty development is the importance of providing faculty with effective strategies for engaging students in meaning making. The Meaningful Processing scale was designed to reflect approaches to deep learning (Barr & Tagg, 1995; Biggs, 1988, 2003; Tagg, 2003) and was the scale most predictive of the Engaged Learning 22 various student success outcomes in this study. Approaches that encourage deep learning involve connecting new learning to what is already inside the learner, an “inside-out” approach that Shulman (2005) asserts is the first step in the learning process. Helping students apply what they are learning to real-world situations and to personal issues in their lives, as well as helping them experience such learning as having the potential to meet their future needs, will lead to the kind of significant learning that lasts beyond the final exam. It is this type of learning that faculty most desire to facilitate within their students, and for which they often seek professional development opportunities. Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory grounded the development of the Engaged Learning Index and thus provides a helpful framework for increasing the levels of students’ engagement that can lead to deep learning. The major premise of their theory is that people are more likely to be authentically motivated when an activity or task meets three of their most basic human needs: their needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. As a wider spectrum of prior learning experiences characterizes today’s college students, the task of motivating students to take responsibility for their own learning has become increasingly daunting and remains the primary challenge for educators (Pintrich & Zusho, 2002). Creating environments that support students’ needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness can lead to higher levels of motivation because such environments foster authentic motivation that is not dependent on extrinsic reinforcers (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Faculty can create such environments within their classrooms, as they are “the designers and facilitators of learning activities and tasks, [who] play a key role in shaping students’ approaches to learning” (Nelson Laird et al., 2008, p. 471). An environment that supports students’ need for competence is characterized by clear expectations, optimal challenges, and Engaged Learning 23 timely feedback (Chickering & Gamson, 1991; Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Kashdan & Fincham, 2004). Instructors can provide clear expectations through a syllabus that outlines how assignments will be assessed and provides helpful information on the structure of the tasks assigned. Emphasizing the meaningfulness of the activity and articulating the level of effort required to master it can also equip students with an increased sense of competence. Optimal challenges occur when the assignment requires students to engage in tasks that realistically stretch their current capabilities (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Boredom and apathy occur when the challenge is too small; anxiety and withdrawal occur when the challenge is too great; curiosity and engagement occur when the challenge is optimal (Kashdan & Fincham, 2004). Timely feedback from faculty fosters competence because it provides information that can be helpful in modifying future performance (Chickering & Gamson, 1991). Frequent feedback that provides information specific to the task enhances students’ perceived competence as it targets specific actions the student can take to move to higher levels of excellence (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Explaining to students at the beginning of a course the types of strategies that are likely to lead to their success also enhances students’ perceived academic control, which researchers have demonstrated is an important factor in their academic success because it is associated with greater investment of effort and increased positive affect (Perry, 2003). Armed with a sense that they are capable of succeeding in class, students are more likely to authentically engage in the learning process. A learning environment that meets students’ need for autonomy also can enhance authentic motivation and lead to deep learning. Providing students with choices and opportunities for self-direction can support their need for autonomy and spark their curiosity. For authentic motivation to occur, students must see themselves as active agents engaged in a Engaged Learning 24 meaningful experience integrated with their own goals and values (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Inherently meaningful assignments tap into students’ interests and require students to think about their talents and how to apply them in a learning situation. Creating opportunities for students to design their own assignments, providing choices in types of assignments which can demonstrate mastery of course concepts, and asking students to connect their learning to important goals in their lives are strategies faculty can utilize to support students’ needs for autonomy. For classes where the structuring of assignments allows for limited choice, exams can be designed to allow students to select from different types of questions or from among several questions to demonstrate their learning. To whatever extent students can see aspects of their academic tasks as chosen and relevant to their own goals, they are more likely to experience engaged learning. Students’ need for relatedness can be supported by learning environments that foster a sense of community. With the proportion of commuter students increasing across all types of institutions, the primary opportunity for developing a psychological sense of community on campus occurs through classroom experiences. A sense of community is comprised of four key elements: (1) membership, or a sense of belonging; (2) ownership, or a sense of voice and contribution; (3) relationship, or emotional connections with others in the community; and (4) partnership, or an interdependence in working toward mutual goals (Schreiner, 1998). Faculty development programs can emphasize that the first day of class sets the tone for the development of this sense of community. As the instructor emphasizes relationships between student and professor, as well as among the students as learning partners, students begin to see themselves as members of a group that will develop into a community. Learning teams enable students to form emotional connections with other students, as well as partnerships that can accomplish more than any individual can. Encouraging feedback from students, such as the “one-minute paper” (Cross, Engaged Learning 25 1998) that many instructors utilize at the end of a class session, fosters the sense of ownership by communicating to students that they have a voice and that their contribution to the class matters. In Kuh et al.’s (2005) study of 20 highly engaging colleges and universities, one common characteristic the institutions manifested was a campus-wide knowledge of their students— “where they came from, their preferred learning styles, their talents, and when and where they need help” (p. 301). Knowledge about one’s students provides faculty with a foundation for connecting with those students’ interests and prior learning. Relating to students authentically enables professors to connect with them in and out of the classroom. A recent study of high-GPA seniors indicated that students were more likely to seek out interaction with faculty outside of class after they had been engaged in the learning process in the classroom and had connected on a personal level with the instructor (Noel, 2007). Thus, faculty development programs that assist faculty in creating a sense of community within their classroom can foster environments that support students’ need for relatedness and are likely to lead to authentic engagement in the learning process. Teaching mindfulness. The third implication of this study for faculty development relates to the significant contribution that focused attention makes to satisfaction with the learning process as well as to college grades, satisfaction with faculty interactions, and overall satisfaction with the college experience. The Focused Attention scale was designed around the construct of mindfulness (Langer, 1997), which can be taught to students, as they learn to be psychologically present in the moment and notice what is new or different in the surrounding environment. Mindfulness also involves perspective-taking (Langer, 1997) and making the material personally meaningful, both of which lead to the deep learning (Tagg, 2003) that tends to have the most significant and lasting impact on students’ lives. Taken together, these strategies also encourage Engaged Learning 26 the development of self-authorship, which is an internally defined belief system and sense of self that one is able to maintain while taking into consideration the views of others (Baxter Magolda, 1999; Kegan, 1994). As faculty teach students to mindfully consider different perspectives, approach issues from a variety of viewpoints, and reframe concepts in a novel way, students are encouraged to take ownership of their learning and begin to internalize their own values and beliefs. Creating a seamless learning environment. Finally, by encouraging faculty to focus intentionally on students’ engagement in the learning process, there is a higher likelihood that students will seek out ways to interact more regularly with faculty outside of class, leading to even greater effects on student learning and success. Congruent with Kuh, Kinzie, Schuh, Whitt, and associates’ (2005) conclusions regarding highly engaging institutions, an “unshakeable focus on student learning” (p. 65) combined with practical ways for fostering engagement in that learning, has a multitude of positive outcomes for students and institutions. An important aspect of faculty development is helping faculty cultivate a greater understanding of the connections that exist between the strategies they utilize in the classroom to facilitate engaged learning and those embedded in student development programming. When faculty view themselves as part of the learning partnerships that can be fostered across campus, a seamless learning environment is created for students inside and outside of class (Baxter Magolda & King, 2004). Limitations of the Study The primary limitation of this study is that the sample, while large and representative in most respects of the institutions from which it was drawn, was not random. Because females were overrepresented and many of the outcomes varied significantly by gender, the sample was weighted for gender (Pike, 2008) and gender was one of the control variables in the regression, Engaged Learning 27 along with ethnicity, first-generation status, degree aspirations, class level, residence, grades, and institutional control (public or private). However, it is possible that a different sample of students may produce slightly different results. The findings reported here are limited to traditionallyaged students at four-year institutions and cannot be generalized to community colleges. Despite this limitation, the reliability and robustness of the constructs measured by the Engaged Learning Index have been confirmed across multiple undergraduate samples within four-year institutions. The current study provides strong support for the dimensions of deep learning, mindfulness, and involvement in learning activities as collectively contributing to students’ learning satisfaction, gains in critical thinking skills, frequency and satisfaction with faculty interaction, total satisfaction with college, and college grades, after controlling for demographic characteristics. Future research can expand on the contribution of engaged learning to additional student success outcomes, including other types of learning gains and student persistence to graduation. A focus on engaged learning as a desired outcome itself, rather than solely as a means to an end, could generate additional research on the types of pedagogy that have the greatest impact on engagement in the learning process. By grounding the constructs of Meaningful Processing, Focused Attention, and Active Participation in well-established theories of motivation and learning, results of the Engaged Learning Index can provide faculty with helpful information about aspects of the teaching and learning process that can enhance students’ authentic motivation for learning. As a result, student responses to the ELI form a valuable foundation for the creation of a faculty development program whose outcome is an increased ability for faculty to facilitate the full scope of student engagement in the learning process within their classrooms. Engaged Learning 28 References Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Personnel, 25, 297-308. Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27(6): 12-25. Baxter Magolda, M. B. (1999). Creating contexts for learning and self-authorship: Constructivedevelopmental pedagogy. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. Baxter Magolda, M. B., & King, P. M. (2004). Learning partnerships: Theory and models of practice to educate for self-authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus. Bean, J. P. (2005, November). A conceptual model of college student engagement. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Philadelphia, PA. Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238-246. Biggs, J. B. (1988). Approaches to learning and to essay writing. In R. R. Schmeck (Ed.), Learning strategies and learning styles (pp. 185-228). New York: Plenum. Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of testing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 445-455). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkage. Research in Higher Education, 47(1), 1-32. Engaged Learning 29 Chickering, A. W., and Gamson, Z. F. (1991). Applying the Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Cross, K. P. (2005). What do we know about students’ learning and how do we know it? Center for the Study of Higher Education, Research and Occasional Paper Series. Accessed online November 16, 2006 at: http://www.aahe.org/nche/cross_lecture.htm Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: Experiencing flow in work and play. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperCollins. Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. Handelsman, M. M., Briggs, W. L., Sullivan, N., & Towler, A. (2005). A measure of college student course engagement. The Journal of Educational Research, 98(3), 184-191. Hu, S., & Kuh, G. D. (2002). Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: The influences of student and institutional characteristics. Research in Higher Education, 43(5), 555-575. Kashdan, T. B., & Fincham, F. D. (2004). Facilitating curiosity: A social and self-regulatory perspective for scientifically based interventions. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 482-503). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kuh, G. D. (2003a). What we are learning about student engagement from NSSE. Change, 35(2), 24-32. Engaged Learning 30 Kuh, G.D. (2003b). The National Survey of Student Engagement: Conceptual framework and overview of psychometric properties. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research and Planning. Kuh, G. D., Gonyea, R. M., & Palmer, M. (2001). The disengaged commuter student: Fact or fiction? Commuter Perspectives, 27, 2-5. Kuh, G. D., Hyek, J. C., Carini, R. M., Ouimet, J. A., Gonyea, R. M., & Kennedy, J. (2001). NSSE technical and norms report. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research and Planning. Kuh G.D., Kinzie, J., Schuh, J.H., Whitt, E.J., and Associates. (2005). Student success in college: Creating conditions that matter. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Langer, E. J. (1997). The power of mindful learning. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Milem, J., & Berger, J. (1997). A modified model of college student persistence: Exploring the relationship between Astin’s theory of involvement and Tinto’s theory of student departure. Journal of College Student Development, 38, 387-400. National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) (2004). Student engagement: Pathways to collegiate success. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) (2005). Exploring different dimensions of student engagement. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) (2006). Engaged learning: Fostering success for all students. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Engaged Learning 31 National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) (2007). Experiences that matter: Enhancing student learning and success. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. Nelson Laird, T. F., Shoup, R., Kuh, G.D., & Schwarz, M. J. (2008). The effects of discipline on deep approaches to student learning and college outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 49, 469-494. Noel, P. M. (2007). Still making a difference in the person I am becoming: A study of students’ perceptions of faculty who make a difference in their lives. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Azusa Pacific University. Olsen, D., Kuh, G. D., Schilling, K. M., Schilling, K., Connolly, M., Simmons, A., & Vesper, N. (1998, November). Great expectations: What first-year students say they will do and what they actually do. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Miami, FL. Pascarella, E. T., et al. (2006). Institutional selectivity and good practices in undergraduate education: How strong is the link? Journal of Higher Education, 77, 251-285. Perry, R. P. (2003). Perceived (academic) control and causal thinking in achievement settings: Markers and mediators. Canadian Psychologist, 44(4), 312-331. Perry, R. P., Hall, N. C., & Ruthig, J. C. (2005). Perceived (academic) control and scholastic attainment in higher education. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 20, pp. 363-436). The Netherlands: Springer. Pike, G. R., & Kuh, G. D. (2005). First- and second-generation college students: A comparison of their engagement and intellectual development. Journal of Higher Education, 76, 276300. Engaged Learning 32 Pintrich, P. R., & Zusho, A. (2002). Student motivation and self-regulated learning in the college classroom. In J. C. Smart & W. G. Tierney (Eds.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 16, pp. 55-128). The Netherlands: Springer. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. Schreiner, L. (1998, July). Building community on college campuses. Paper presented at the National Conference on Student Retention, New Orleans, LA. Schreiner, L. A., & Louis, M. (2006, November). Measuring engaged learning in college students: Beyond the borders of NSSE. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, Anaheim, CA. Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Rawsthorne, L., & Ilardi, B. (1997). Trait self and true self: Crossrole variation in the Big Five traits and its relations with authenticity and subjective wellbeing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1380-1393. Shulman, L. S. (2005). Making differences: A table of learning. Change, 34(6), 36-44. Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., Eddy, P. L., & Beach, A. L. (2006). Creating the future of faculty development. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing. Tagg, J. (2003). The learning paradigm college. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing. Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association.