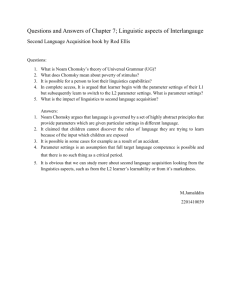

Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Ferdinand de Saussure (November 26, 1857 - February 22,

1913) was a Swiss linguist.

Born in Geneva, he laid the foundation for many developments in linguistics in the 20th century. He perceived linguistics as a branch of a general science of signs he proposed to call semiology (now generally known as semiotics).

His work

Cours de linguistique générale

(Course in General

Linguistics) was published posthumously in 1916 by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye based on lecture notes. This became one of the seminal linguistics works of the 20th century. Its central notion is that language can be analyzed as a formal system of organized difference, apart from the messy dialectics of realtime production and comprehension. Additionally, at a very young age he published a very important work in Indo-European philology which put forward what is now known as the laryngeal theory. It has been argued that the problem of trying to explain how he himself was able to make systematic predictive hypotheses from known linguistic data to unknown linguistic data, stimulated his development of structuralism.

His work had two receptions which developed it in two very different ways. In America it flowered as developed by Leonard Bloomfield into distributionalism, and has since then been presupposed by all linguistic science. This Saussurean influence, however, has been disavowed by Noam Chomsky, among others. In contemporary developments, it has been most explicitly developed by Michael Silverstein who has combined it with the theories of markedness and distinctive features the Prague School (most importantly Nikolay Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson invented for the plane of analysis of phonology, the Sapir-Whorfian theory of the grammatical category, and the insight of transformational analysis, in order to analyze the plane of Saussurean sense proper. In Europe, important contributions were quickly made by Emile Benveniste, Antoine Meillet, and Andre Martinet, among others.

However, structuralism was soon picked up and calqued by students of other, non-linguistic aspects of culture, such as Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. Their expansive interpretations of Saussure's theories, and their application of those theories to nonlinguistic fields of study led to theoretical difficulties, eventually causing proclamations of the

"death" of structuralism in those disciplines.

"A sign is the basic unit of langue (a given language at a given time). Every langue is a complete system of signs. Parole (the speech of an individual) is an external manifestation of langue."

Cours de linguistique générale

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Ferdinand de Saussure's Cours de linguistique générale was published posthumously in

1916 by Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye based on lecture notes. It is generally seen as being the origin of structuralism. Although Saussure was, like his contemporaries, interested in historical linguistics, the Cours develops a theory of semiology that is applicable more generally.

Semiology: Langage, Langue, and Parole

Saussure focuses on what he calls langage , that is "a system of signs that express ideas", and suggests that it may be divided into two components: langue , referring to the abstract system of language, and parole , referring, in essence, to speech or the "putting into practice of language". Saussure argued against the popular organicist view of language as a natural organism, which, without being determinable by the will of man, grows and evolves in accordance with fixed laws. Instead, he defined language as a social product; the social side of speech outside of the speaker’s control. According to Saussure, language is not a function of the speaker, but is passively assimilated. Speaking, as defined by Saussure, is a premeditated act.

While speech (parole) is heterogeneous, that is to say, it is composed of unrelated or differing parts or elements, language (langue) is homogeneous, composed of the union of meanings and sound images in which both parts are psychological. Therefore, as langue is systematic, it is this that Saussure focuses on since it allows an investigative methodology that is rooted, supposedly, in pure science. Beginning with the Greek word ‘semîon’ meaning 'sign’,

Saussure names this science semiology: ‘a science that studies the life of signs within society’.

The Sign

The focus of Saussure’s investigation is the linguistic unit or sign.

Fig. 1 - The Sign

The sign ( signe ) is described as a "double entity", made up of the signifier, or sound image,

( signifiant ), and the signified, or concept ( signifié

). The sound image is a psychological NOT material concept (a poem can be mentally recited). Both components of the linguistic sign are inseparable. The easiest way to appreciate this is to think of them as being like either side of a piece of paper - one side simply cannot exist without the other.

But the relationship between signifier and signified is not quite that simple. Saussure is adamant that language cannot be considered a collection of names for a collection of objects

(as where Adam is said to have named the animals). According to Saussure, language is not a nomenclature.

Arbitrariness

The basic principle of the arbitrariness of the sign ( l'arbitraire du signe ) in the extract is: there is no natural reason why a particular sign should be attached to a particular concept.

Fig. 2 - Arbitrariness

In Figure 2 above, the signified "tree" is impossible to represent because the signified is entirely conceptual. There is no definitive (ideal, archetypical) "tree". Even the picture of a tree Saussure uses to represent the signified is itself just another signifier. This aside, it is

Saussure's argument that it is only the consistency in the system of signs that allows communication of the concept each sign signifies.

The object itself - a real tree, in the real world - is the referent. For Saussure, the arbitrary involves not the link between the sign and its referent but that between the signifier and the signified in the interior of the sign.

In Jabberwocky , Lewis Carroll exploits the arbitrary nature of the sign in its use of nonsense words. The poem also demonstrates very clearly the concept of the sign as a two sided psychological entity, since it is impossible to read the nonsense words without assigning a possible meaning to them. We naturally assume that there is a signified to accompany the signifier.

The concepts of signifier and signified could be compared with the Freudian concepts of latent and manifest meaning. Freud was also inclined to make the assumption that signifiers and signifieds are inseparably bound. Humans tend to assume that all expressions of language mean something.

In further support of the arbitrary nature of the sign, Saussure goes on to argue that if words stood for pre-existing concepts they would have exact equivalents in meaning from one language to the next and this is not so. Different languages divide up the world differently. To explain this, Saussure uses the word bœf

as an example. He cites the fact that while, in

English, we have different words for the animal and the meat product: Ox and beef , in French, bœuf is used to refer to both concepts. A perception of difference between the two concepts is absent from the French vocabulary. In Saussure's view, particular words are born out of a particular society’s needs, rather than out of a need to label a pre-existing set of concepts.

Saussure himself identifies a number of flaws in this concept of arbitrariness. First, in order to allow for numerical systems, Saussure is forced to admit to degrees of arbitrariness. That is because, though twenty and two might be arbitrary representations of a numerical concept, twenty-two , twenty-three etc. are named as part of a system and therefore the signifier is not entirely arbitrary. This is illustrated equally by roman numerals.

I II III IV V VI

Fig. 3 - Degrees of Arbitrariness

A further issue is onomatopoeia. Saussure recognised that his opponents could argue that with onomatopoeia there is a direct link between word and meaning, signifier and signified.

However, Saussure argues that, on closer etymological investigation, onomatopoeic words can, in fact, be coincidental, evolving from non-onomatopoeic origins. The example he uses is the French and English onomatopoeic words for a dog's bark, that is Bow Wow and Oua Oua .

Finally, Saussure considers interjections and dismisses this obstacle with much the same argument i.e. the sign / signifier link is less natural than it initially appears. He invites readers to note the contrast in pain interjection in French ( aie ) and English ( ouch ).

Difference

Saussure states: "[a sign’s] most precise characteristic is to be what the others are not". In other words, signs are defined by what they are not. An example may be found in Blackadder:

After burning the only copy of Johnson's Dictionary, Blackadder and Baldric attempt to rewrite it themselves. Baldric comes up with: "Dog: Not a cat" - a more accurate definition than it might seem in light of Saussure.

Difference in language is unique; Saussure writes: "In language there are only differences.

Even more important: a difference generally implies positive terms between which the difference is set up; but in language there are only differences without positive terms...The idea of phonic substance that a sign contains is of less importance than the other signs that surround it."

But, shortly thereafter, he adds: "But the statement that everything in language is negative is true only if the signified and the signifier are considered separately; when we consider the sign in its totality, we have something that is positive in its own class."

It is frequently argued that Saussure's emphasis on difference is somehow incompatible with communication, the use of language or parole, which is obviously more than a nosedive into an abyss of difference. But Saussure acknowledges the positive value of the sign; in this case, too, a chess metaphor comes up. If, during a game, a piece is lost - for example, the set is short a bishop - any object could replace it (a salt shaker, a thimble, a candy corn), but as long as the substitute is set into the board it functions as a bishop and it is that function that confers value upon it.

The Synchronic and Diachronic Axes

Language that is studied synchronically is "studied as a complete system at a given point in time" (The AB axis). Language studied diachronically is "studied in its historical development" (The CD axis). Saussure argues that we should be concerned with the AB axis

(in addition to the CD axis, which was the focus of attention in Saussure's time), because, he says, language is "a system of pure values which are determined by nothing except the momentary arrangements of its terms".

Fig. 4 - The Synchronic and Diachronic Axes

To illustrate this, Saussure uses a chess metaphor. In chess, a person joining a game’s audience mid-way through requires no more information than the present layout of pieces on the board. They would not benefit from knowing how the pieces came to be arranged in this way.

Structuralism

Structuralism is a general approach in various academic disciplines that seeks to explore the inter-relationships between some fundamental elements, upon which higher mental, linguistic, social, cultural etc "structures" are built, through which then meaning is produced within a particular person, system, culture.

Structuralism appeared in academic psychology for the first time in the 19th century and then reappeared in the second half of the 20th century, when it grew to become one of the most popular approaches in the academic fields that are concerned with analyzing language, culture, and society. Ferdinand de Saussure is generally considered a starting point of the 20th century structuralism. As with any cultural movement, the influences and developments are complex.

Structuralism in psychology (19th century)

At the turn of 19th century the founding father of experimental psychology Wilhelm Wundt tried to experimentally confirm his hypothesis that conscious mental life can be broken down into fundamental elements which then form more complex mental structures. In this part of the 19th century, researchers were making great advances in chemistry and physics by analysing complex compounds (molecules) in terms of their elements (atoms). These successes encouraged psychologists to look for the mental elements of which more complex experiences were composed. If the chemist made headway by analysing water in terms of oxygen and hydrogen, perhaps the psychologist could make headway by considering the taste of lemonade (perception) to be a molecule of conscious experience to be analysed in terms of elements (sensations) - such as : sweet, sour, cold, warm, bitter, and whatever that could be identified by introspection (observation). A major believer was the psychologist Edward B.

Titchener who was trained by Wundt and worked at Cornell University. Since the goal was to specify mental structures, Titchener coined the phrase structuralism to describe this branch of psychology (Atkinson, R.L. 1990, Introduction to Psychology. (10th Ed) New York, Harcourt

Brace Jovanovich, p767). Wundt's structuralism was quickly abandoned because it could not be tested in the same way as behaviour. Today, however, the brain-scanning technology can identify, for example, specialized brain cells that respond exclusively to basic lines and shapes and are then combined in subsequent brain areas where more complex visual structures are formed. This line of research in modern psychology is called cognitive psychology rather then structuralism because Wundt's term never ceased to be associated with the problem of observability.

Structuralism in linguistics

Ferdinand de Saussure is the originator of the 20th century reappearance of structuralism, specifically in his 1916 book Course in General Linguistics , where he focused not on the use of language ( parole , or talk), but rather on the underlying system of language ( langue ) and called his theory semiotics . This approach focused on examining how the elements of language related to each other in the present, that is, 'synchronically' rather than

'diachronically'. Finally, he argued that linguistic signs were composed of two parts, a signifier (the sound pattern of a word, either in mental projection - as when we silently recite

lines from a poem to ourselves - or in actual, physical realization as part of a speech act) and a signified (the concept or meaning of the word).

This was quite different from previous approaches which focused on the relationship between words and the things in the world they designated. By focusing on the internal constitution of signs rather than focusing on their relationship to objects in the world, Saussure made the anatomy and structure of language something that could be analyzed and studied.

Saussure's Course influenced many linguists in the period between WWI and WWII. In

America, for instance, Leonard Bloomfield developed his own version of structural linguistics, as did Louis Hjelmslev in Scandinavia. In France Antoine Meillet and Émile

Benveniste would continue Saussure's program. Most importantly, however, members of the

Prague School of linguistics such as Roman Jakobson and Nikolai Trubetzkoy conducted research that would be greatly influential.

The clearest and most important example of Prague School structuralism lies in phonemics.

Rather than simply compile a list of which sounds occur in a language, the Prague School sought to examine how they were related. They determined that the inventory of sounds in a language could be analyzed in terms of a series of contrasts. Thus in English the words 'pat' and 'bat' are different because the /p/ and /b/ sounds contrast. The difference between them is that the vocal chords vibrate while saying a /b/ while they do not when saying a /p/. Thus in

English there is a contrast between voiced and non-voiced consonants. Analyzing sounds in terms of contrastive features also opens up comparative scope - it makes clear, for instance, that the difficulty Japanese speakers have differentiating between /r/ and /l/ in English is due to the fact that these two sounds are not contrastive in Japanese. While this approach is now standard in linguistics, it was revolutionary at the time. Phonology would become the paradigmatic basis for structuralism in a number of different forms.

Structuralism in anthropology

According to structural theory in anthropology, meaning within a culture is produced and reproduced through various practices, phenomena and activities which serve as systems of signification. A structuralist studies activities as diverse as food preparation and serving rituals, religious rites, games, literary and non-literary texts, and other forms of entertainment to discover the deep structures by which meaning is produced and reproduced within a culture. For example, an early and prominent practitioner of structuralism, anthropologist and ethnographer Claude Lévi-Strauss in the 1950s, analyzed cultural phenomena including mythology, kinship, and food preparation (see also structural anthropology). In addition to these more linguistically-focused writings where he applied Saussure's distinction between langue and parole in his search for the fundamental mental structures of the human mind, arguing that the structures that form the "deep grammar" of society originate in the mind and operate in us unconsciously, Levi-Strauss was inspired by information theory and mathematics.

Another concept was borrowed from the Prague school of linguistics, where Roman Jakobson and others analysed sounds based on the presence or absence of certain features (such as voiceless vs. voiced). Levi-Strauss included this in his conceptualization of the universal structures of the mind, which he held to operate based on pairs of binary oppositions such as hot-cold, male-female, culture-nature, cooked-raw, or marriageable vs. tabooed women. A third influence came from Marcel Mauss, who had written on gift exchange systems. Based

on Mauss, for instance, Lévi-Strauss argued that kinship systems are based on the exchange of women between groups (a position known as 'alliance theory') as opposed to the 'descent' based theory described by Edward Evans-Pritchard and Meyer Fortes.

Lévi-Strauss writing was popular in the 1960s and 1970s. In Britain authors such as Rodney

Needham and Edmund Leach were highly influenced by structuralism. Authors such as

Maurice Godelier and Emmanuel Terray combined Marxism with structural anthropology in

France. In America, authors such as Marshall Sahlins and James Boon build on structuralism to provide their own analysis of human society. Structural anthropology fell out of favour in the early 1980s for a number of reasons. D'Andrade (1995) suggests that structuralism in anthropology was eventually abandoned because it made unverifiable assumptions about the universal structures of the human mind. Authors such as Eric Wolf argued that political economy and colonialism should be more at the forefront of anthropology. More generally, criticisms of structuralism by Pierre Bourdieu led to a concern with how cultural and social structures were changed by human agency and practice, a trend which Sherry Ortner has referred to as 'practice theory'.

Structuralism in the Philosophy of Mathematics

Structuralism in mathematics is the study of what structures say a mathematical object is, and how the ontology of these structures should be understood. This is a growing philosophy within mathematics that is not without its share of critics.

In 1965, Paul Benacerraf wrote a paper entitled: "What Numbers Could Not Be." This paper is a seminal paper on mathematical structuralism in an odd sort of way: it started the movement by the response it generated. Benacerraf addressed a notion in mathematics to treat mathematical statements at face value, in which case we are committed to a world of an abstract, eternal realm of mathematical objects. Bernacerraf's dilemma is how do we come to know these objects if we do not stand in causal relation to them. These objects are considered causally inert to the world. Another problem raised by Bernacerraf is the multiple set theories that exist by which reduction of elementary number theory to sets is possible. Deciding which set theory is true has not been feasible. Benacerraf concluded in 1965 that numbers are not objects, a conclusion responded to by Mark Balugar with the introduction of full blodded platonism (FBP is essentially the view that all logically possible mathematical objects do exist). With FBP it does not matter which set-theoretic construction of mathematics is used nor how we came to know of its existance since any consistent mathematical theory necessarily exists and is a part of the greaterp platonic realm.

The answer to Benacerraf's negative claims is how structuralism became a viable philosophical program within mathematics. The structuralist responds to these negative claims that the essence of mathematical objects is relations that the objects bear with the structure.

Structures are exemplified in abstract systems in terms of the relations that hold true for that system.

Important contributions to structuralism in Mathematics have been made by Bourbaki.

Structuralism in the Literary Theory and Literary

Criticism

In literary theory structuralism is an approach to analysing the narrative material by examining the underlying invariant structure. For example, a literary critic applying a structuralist literary theory might criticise the authors of the West Side Story by claiming that they did not write anything "really" new , because they wrote just "yet another" paraphrase of the structure of the classical Romeo and Juliet text. In both texts a girl and a boy fall in love (a

"formula" with a symbolic operator between them would be "Boy +LOVE Girl") despite the fact that they belong to two groups that hate each other ("Boy's Group -LOVE Girl's Group") and conflict is resolved by their death. On the other hand, such a literary criticist could make the same claim about a rather different story of two friendly families ("Boy's Family +LOVE

Girl's Family") that make an arranged marriage between their children despite the fact that they hate each other ("Boy -LOVE Girl") and the children commit suicide to escape the arranged marriage, because this second story's structure can be seen as an 'inversion' of the first story's structure, since the relationship between the values of love and the two pairs of parties involved have been reversed. In sum, a structuralistic literary criticism argues that the

"novelty value of a literary text" can lay only in new structure, rather than in the specifics of character development and voice in which that structure is expressed.

Structuralism after World War II

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, existentialism like that practiced by Jean-Paul Sartre was the dominant mood. Structuralism surged to prominence in France after WWII and particularly in the 1960s. The initial popularity of structuralism in France led it to spread across the globe.

Structuralism rejected the concept of human freedom and choice and focused instead on the way that human behavior is determined by various structures. The most important initial work on this score was Claude Lévi-Strauss's 1949 volume Elementary Structures of Kinship

. Lévi-

Strauss had known Jakobson during their time together in New York during WWII and was influenced by both Jakobson's structuralism as well as the American anthropological tradition.

In Elementary Structures he examined kinship systems from a structural point of view and demonstrated how apparently different social organizations were in fact different permutations of a few basic kinship structures. In the late 1950s he published Structural

Anthropology , a collection of essays outlining his program for structuralism.

By the early 1960s structuralism as a movement was coming into its own and some believed that it offered a single unified approach to human life that would embrace all disciplines.

Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida focused on how structuralism could be applied to literature.

Blending Freud and De Saussure, the infamous French (post)structuralist Jacques Lacan and, in a different way, Jean Piaget, applied structuralism to the study of psychoanalysis and psychology each respectively.

Michel Foucault's book The Order of Things examined the history of science to study how structures of epistemology, or episteme shaped how people imagined knowledge and knowing

(though Foucault would later explicitly deny affiliation with the structuralist movement).

Blending Marx and structuralism another French theorist Louis Althusser introduced his own brand of structural social analysis. Other authors in France and abroad have since extended structural analysis to practically every discipline.

The definition of 'structuralism' also shifted as a result of its popularity. As its popularity as a movement waxed and waned, some authors considered themselves 'structuralists' only to later eschew the label.

The term has slightly different meanings in French and English. In the US, for instance,

Derrida is considered the paradigm of post-structuralism while in France he is labeled a structuralist. Finally, some authors wrote in several different styles. Barthes, for instance, wrote some books which are clearly structuralist and others which are clearly not.

Reactions to structuralism

Today structuralism has been superseded by approaches such as post-structuralism and deconstruction. There are many reasons for this. Structuralism has often been criticized for being ahistorical and for favoring deterministic structural forces over the ability of individual people to act. As the political turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s (and particularly the student uprisings of May 1968) began affecting academia, issues of power and political struggle moved to the center of people's attention. In the 1980s, deconstruction and its emphasis on the fundamental ambiguity of language - rather than its crystalline logical structure - became popular. By the end of the century Structuralism was seen as a historically important school of thought, but it was the movements it spawned, rather than structuralism itself, which commanded attention.

Leonard Bloomfield

Leonard Bloomfield (1887 - 1949) was an American linguist, whose influence dominated the development of structural linguistics in America between the 1930s and the 1950s. He is especially known for his book Language (1933), describing the state of the art of linguistics at its time.

Bloomfield's thought was mainly characterized by its behavioristic principles for the study of meaning, its insistence on formal procedures for the analysis of language data, as well as a general concern to provide linguistics with rigorous scientific methodology. Its pre-eminence decreased in the late 1950s and 1960s, after the emergence of Generative Grammar.

Bloomfield also began the genetic examination of the Algonquian language family with his reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian; his seminal paper on the family remains a cornerstone of

Algonquian historical linguistics today.

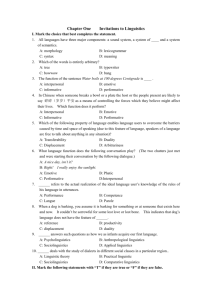

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky, Ph.D. (born December 7, 1928) is the Institute Professor Emeritus of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Chomsky is credited with the creation of the theory of generative grammar, often considered the most significant contribution to the field of theoretical linguistics of the 20th century. He also helped spark the cognitive revolution in psychology through his review of B. F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior , which challenged the behaviorist approach to the study of mind and language dominant in the

1950s. His naturalistic approach to the study of language has also impacted the philosophy of language and mind (see Harman, Fodor). He is also credited with the establishment of the socalled Chomsky hierarchy, a classification of formal languages in terms of their generative power.

Along with his lingustics work, Chomsky is also widely known for his political activism, and for his criticism of the foreign policy of the United States and other governments. Chomsky describes himself as a libertarian socialist, a sympathizer of anarcho-syndicalism, and is often considered to be a key intellectual figure within the American left, or far-left.

According to the Arts and Humanities Citation Index, between 1980 and 1992 Chomsky was cited as a source more often than any living scholar, and the eighth most cited source overall.

Biography

Chomsky was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the son of Hebrew scholar William Chomsky, who was from a town in Ukraine later wiped out by the Nazis. His mother, Elsie Chomsky née

Simonofsky, came from what is now called Belarus, but unlike her husband she grew up in America and normally spoke "ordinary New York

English". Their first language was Yiddish, but Chomsky says it was "taboo" in his family to speak it. He describes his family as living in a sort of "Jewish ghetto", split into a "Yiddish side" and "Hebrew side", with his family aligning with the latter and bringing him up "immersed in Hebrew culture and literature."

At the age of eight or nine, Chomsky spent every Friday night reading Hebrew literature. [1] Later in life he would teach Hebrew classes. In spite of this, and of all the linguistic work carried out during his career,

Chomsky claims "the only language I speak and write proficiently is English."

Chomsky remembers the first article he wrote was at the age of ten about the threat of the spread of fascism, following the fall of Barcelona. From the age of twelve or thirteen he identified more fully with anarchist politics.

Starting in 1945, he studied philosophy and linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, learning from philosopher C. West Churchman and linguist Zellig Harris. Harris' political views were instrumental in shaping those of Chomsky.

In 1949, Chomsky married linguist Carol Schatz. They have two daughters, Avi and Diane, and a son, Harry.

Chomsky received his Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania in 1955. He conducted much of his doctoral research during four years at Harvard University as a Harvard Junior Fellow. In his doctoral thesis, he began to develop some of his linguistic ideas, elaborating on them in his 1957 book Syntactic Structures, perhaps his best-known work in the field of linguistics.

Chomsky joined the staff of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1955 and in 1961 was appointed full professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics (now the Department of Linguistics and

Philosophy.) From 1966 to 1976 he held the Ferrari P. Ward Professorship of Modern Languages and

Linguistics. In 1976 he was appointed Institute Professor. He has been teaching at MIT continuously for the last

50 years.

It was during this time that Chomsky became more publicly engaged in politics: he became one of the leading opponents of the Vietnam War with the publication of his essay "The Responsibility of Intellectuals" [2] in The

New York Review of Books in 1967. Since that time, Chomsky has become well known for his political views, speaking on politics all over the world, and writing numerous books. His far-reaching criticism of US foreign policy and the legitimacy of US power has made him a controversial figure. He has a devoted following among the left, but he has also come under increasing criticism from liberals as well as from the right, particularly because of his response to the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Contributions to linguistics

Syntactic Structures was a distillation of his book Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory

(1955, 75) in which he introduces transformational grammars. The theory takes utterances

(sequences of words) to have a syntax which can be (largely) characterised by a formal grammar; in particular, a Context-free grammar extended with transformational rules.

Children are hypothesised to have an innate knowledge of the basic grammatical structure common to all human languages (i.e. they assume that any language which they encounter is of a certain restricted kind). This innate knowledge is often referred to as universal grammar.

It is argued that modelling knowledge of language using a formal grammar accounts for the

"productivity" of language: with a limited set of grammar rules and a finite set of terms, humans are able to produce an infinite number of sentences, including sentences no one has previously said.

The Principles and Parameters approach (P&P) — developed in his Pisa 1979 Lectures, later published as Lectures on Government and Binding (LGB) — make strong claims regarding universal grammar: that the grammatical principles underlying languages are innate and fixed, and the differences among the world's languages can be characterized in terms of parameter settings in the brain (such as the pro-drop parameter, which indicates whether an explicit subject is always required, as in English, or can be optionally dropped, as in Spanish), which are often likened to switches. (Hence the term principles and parameters, often given to this approach.) In this view, a child learning a language need only acquire the necessary lexical items (words, grammatical morphemes, and idioms), and determine the appropriate parameter settings, which can be done based on a few key examples.

Proponents of this view argue that the pace at which children learn languages is inexplicably rapid, unless children have an innate ability to learn languages. The similar steps followed by children all across the world when learning languages, and the fact that children make certain characteristic errors as they learn their first language, whereas other seemingly logical kinds of errors never occur (and, according to Chomsky, should be attested if a purely general, rather than language-specific, learning mechanism were being employed), are also pointed to as motivation for innateness.

More recently, in his Minimalist Program (1995), while retaining the core concept of

"principles and parameters" , Chomsky attempts a major overhaul of the linguistic machinery involved in the LGB model, stripping it from all but the barest necessary elements, while advocating a general approach to the architecture of the human language faculty that emphasises principles of economy and optimal design , reverting to a derivational approach to generation, in contrast with the largely representational approach of classic P&P .

Chomsky's ideas have had a strong influence on researchers investigating the acquisition of language in children, though some researchers who work in this area today do not support

Chomsky's theories, often advocating emergentist or connectionist theories reducing language to an instance of general processing mechanisms in the brain.

Generative grammar

The Chomskyan approach towards syntax, often termed generative grammar, though quite popular, has been challenged by many, especially those working outside the United States.

Chomskyan syntactic analyses are often highly abstract, and are based heavily on careful investigation of the border between grammatical and ungrammatical constructs in a language.

(Compare this to the so-called pathological cases that play a similarly important role in mathematics.) Such grammaticality judgments can only be made accurately by a native speaker, however, and thus for pragmatic reasons such linguists often focus on their own native languages or languages in which they are fluent, usually English, French, German,

Dutch, Italian, Japanese or one of the Chinese languages. However, as Chomsky has said:

The first application of the approach was to Modern Hebrew, a fairly detailed effort in

1949–50. The second was to the native American language Hidatsa (the first full-scale generative grammar), mid-50s. The third was to Turkish, our first Ph.D. dissertation, early 60s. After that research on a wide variety of languages took off. MIT in fact became the international center of work on Australian Aboriginal languages within a generative framework [...] thanks to the work of Ken Hale, who also initiated some of the most far-reaching work on Native American languages, also within our program; in fact the first program that brought native speakers to the university to become trained professional linguists, so that they could do work on their own languages, in far greater depth than had ever been done before. That has continued. Since that time, particularly since the 1980s, it constitutes the vast bulk of work on the widest typological variety of languages.

Sometimes generative grammar analyses break down when applied to languages which have not previously been studied, and many changes in generative grammar have occurred due to an increase in the number of languages analyzed. However, the claims made about linguistic universals have become stronger rather than weaker over time; for example, Richard Kayne's suggestion in the 1990s that all languages have an underlying Subject-Verb-Object word order would have seemed implausible in the 1960s. One of the prime motivations behind an alternative approach, the functional-typological approach or linguistic typology (often associated with Joseph Greenberg), is to base hypotheses of linguistic universals on the study of as wide a variety of the world's languages as possible, to classify the variation seen, and to form theories based on the results of this classification. The Chomskyan approach is too indepth and reliant on native speaker knowledge to follow this method, though it has over time been applied to a broad range of languages.

Chomsky hierarchy

Chomsky is famous for investigating various kinds of formal languages and whether or not they might be capable of capturing key properties of human language. His Chomsky hierarchy partitions formal grammars into classes, or groups, with increasing expressive power, i.e., each successive class can generate a broader set of formal languages than the one before.

Interestingly, Chomsky argues that modelling some aspects of human language requires a

more complex formal grammar (as measured by the Chomsky hierarchy) than modeling others. For example, while a regular language is powerful enough to model English morphology, it is not powerful enough to model English syntax. In addition to being relevant in linguistics, the Chomsky hierarchy has also become important in computer science

(especially in compiler construction and automata theory).

His best-known work in phonology is The Sound Pattern of English , written with Morris

Halle. This work is considered outdated (though it has recently been reprinted), and Chomsky does not publish on phonology anymore.

Chomsky's influence in other fields

Chomskyan models have been used as a theoretical basis in several other fields. The Chomsky hierarchy is often taught in fundamental computer science courses as it confers insight into the various types of formal languages. This hierarchy can also be discussed in mathematical terms [4], and has generated interest among mathematicians, particularly combinatorialists. A number of arguments in evolutionary psychology are derived from his research results.

The 1984 Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine and Physiology, Niels K. Jerne, used Chomsky's generative model to explain the human immune system, equating "components of a generative grammar ... with various features of protein structures". The title of Jerne's Stockholm Nobel lecture was "The Generative Grammar of the Immune

System."

Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who according to some researchers learned 125 signs in ASL, was named after

Noam Chomsky.

Worldwide audience

Despite Chomsky's alleged marginalization in the mainstream US media, Chomsky is one of the most globally famous figures of the left, especially among academics and university students, and frequently travels across the

United States, Europe, and the Third World. He has a very large following of supporters worldwide as well as a dense speaking schedule, drawing large crowds wherever he goes. He is often booked up to two years in advance. He was one of the main speakers at the 2002 World Social Forum. He is interviewed at length in alternative media [29] Many of his books are bestsellers, including 9-11 . [30]

The 1992 film Manufacturing Consent , shown widely on college campuses and broadcast on PBS, gave

Chomsky a younger audience. In a 1995 article in REVelation , Alex Burns described the film as a "double edged sword--it brought Chomsky's work to a wider audience and made it accessible, yet it has also been used by younger activists to idolise him, creating a 'cult of personality.'" [31]

Chomsky's popularity has become a cultural phenomenon. Bono of U2 called Chomsky a "rebel without a pause, the Elvis of academia." Rage Against The Machine took copies of his books on tour with the band. Pearl Jam ran a small pirate radio on one of their tours, playing Chomsky talks mixed along with their music. R.E.M. asked

Chomsky to go on tour with them and open their concerts with a lecture (he declined). Chomsky lectures have been featured on the B-sides of records from Chumbawamba and other groups. [32] Many anti-globalization and anti-war activists regard Chomsky as an inspiration.

Chomsky is widely read outside the US. 9-11 was published in 26 countries and translated into 23 foreign languages [33]; it was a bestseller in at least five countries, including Canada and Japan [34]. Chomsky's views are often given coverage on public broadcasting networks around the world- a fact supporters say is in marked contrast to his rare appearances in the US media. In the UK, for example, he appears frequently on the BBC.

Academic Achievements, Awards and Honors

According to the Arts and Humanities Citation Index, between 1980 and 1992 Chomsky was cited as a source more often than any living scholar, and the eighth most cited source overall.

In the spring of 1969 he delivered the John Locke Lectures at Oxford University; in

January 1970 he delivered the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lecture at Cambridge

University; in 1972, the Nehru Memorial Lecture in New Delhi, in 1977, the

Huizinga Lecture in Leiden, in 1997, The Davie Memorial Lecture on Academic

Freedom in Cape Town, among many others.

Noam Chomsky has received honorary degrees from University of London,

University of Chicago, Loyola University of Chicago, Swarthmore College, Delhi

University, Bard College, University of Massachusetts, University of Pennsylvania, Georgetown University,

Amherst College, Cambridge University, University of Buenos Aires, McGill University, Universitat Rovira I

Virgili, Tarragona, Columbia University, University of Connecticut, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, University of Western Ontario, University of Toronto, Harvard University, University of Calcutta, and Universidad

Nacional De Colombia. He is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National

Academy of Science. In addition, he is a member of other professional and learned societies in the United States and abroad, and is a recipient of the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award of the American Psychological

Association, the Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences, the Helmholtz Medal, the Dorothy Eldridge Peacemaker Award, the Ben Franklin Medal in Computer and Cognitive Science, and others. He is twice winner of The Orwell

Award, granted by The National Council of Teachers of English for "Distinguished Contributions to Honesty and Clarity in Public Language." [36]

Chomsky was voted the leading living public intellectual in The 2005 Global Intellectuals Poll conducted by the

British magazine Prospect . He reacted coolly, saying "I don't pay a lot of attention to [polls]."

Criticism of Chomsky's work in linguistics

While Chomsky's is the best known position in linguistics, his views have been criticized. His original work in linguistics, dating to the 1950s, is widely regarded as an important step in the development of ties between language studies and the cognitive sciences. To some degree, his earlier concepts of generative grammar have been supplanted or reconceived in terms from cognitive science, rather than in terms used in language studies of the time. Current linguistics literature boasts many important alternatives to Chomsky's specific models of syntax, though most owe much to Chomsky's work. Prominent among these are Head-Driven Phrase

Structure Grammar and Lexical Functional Grammar. These proposals differ from Chomsky's principally in the types of structures assumed, and in the search for "representational" alternatives to step-by-step computation (called "derivation" in Chomskyan work). Another more radical alternative to Chomsky's position is that proposed by George Lakoff and Mark

Johnson. Their cognitive linguistics was developed out of Chomskyan linguistics but differs from it in significant ways. Specifically, they argue against the neo-Cartesian aspects of

Chomsky's theories, and state that Chomsky fails to take account of the extent to which cognition is embodied.

Another strong source of criticism of Chomsky's linguistics comes from some researchers who study language acquisition. Many researchers in this field do not take a Chomskyan approach, and some, such as Michael Tomasello and Elizabeth Bates, have been very critical of the Chomskyan approach to language learning. Most of this criticism surrounds

Chomskyan concepts of innateness. Controversy surrounds the extent and nature of evidence for the principles and parameters approach to language acquisition (which suggests that a significant portion of language learning involves setting a finite and predetermined set of

parameters). Tomasello has argued that children's early utterances lack syntactic structure, and Bates suggests that early linguistic behavior is far more compatible with connectionist or emergentist views of learning, which do not need to posit any preexisting structure. In reply, researchers such as Kenneth Wexler and Lila Gleitman disagree with the assertion that children's early utterances have no syntactic structure and argue that there is in fact evidence for the acquisition of syntactic parameters in early speech -- for example, acquisition of the

"verb second" property of German in the second year of life.

Some researchers in computational linguistics are also critical of Chomsky's approach to language learning. Chomskyan theories of syntax (since they are concerned with modelling linguistic competence) have very little to say about the actual process of language acquisition, and most research in language acquisition has had to rely on statistical modelling to produce working models of syntactic comprehension. Some have argued that such models are hard to integrate with Chomskyan theories of linguistic competence (in particular, theories in the principles and parameters framework).

In a much more radical way, philosophers in the tradition of Wittgenstein (such as Saul

Kripke) argue that Chomskyans are fundamentally wrong about the role of rule following in human cognition. In a similar way philosophers in the phenomenological/existential/hermeneutic traditions oppose the abstract neo-rationalist aspects of Chomsky's thought. The contemporary philosopher who best represents this view is, perhaps, Hubert Dreyfus, also famous (or notorious) for his attacks on artificial intelligence.

Another common criticism of Chomskyan analyses of specific languages is that they force languages into an English-like mold. There might once have been justice to this criticism.

English (Chomsky's native language) was the first language whose syntax was subjected to serious investigation from a Chomskyan perspective. English-specific results were thus the natural starting point for the investigation of other languages. Since the late 1970s, however, as the field assimilated data from a wide variety of languages (and the field itself was increasingly internationalized), this criticism has been heard with decreasing frequency -- especially as it has become clear that in many respects, English is a typological outlier among languages.

The "autonomy" of syntax has received much criticism. In particular the work of Anna

Wierzbicka argues that syntax is semantically motivated. Chomsky's own position on the relationship between syntax and semantics is somewhat unclear, since he thinks that much of what is called semantics is actually syntax (since it involves the rule-based manipulation of abstract symbols). However, Chomsky is often regarded as an advocate of an autonomous syntax.

Roman Jakobson

Roman Osipovich Jakobson (October 11, 1896 - July 18, 1982) was a Russian thinker who became one of the most influential linguists of the 20th century by pioneering the development of structural analysis of language, poetry, and art.

Jakobson was born to a well-to-do family in Russia, where he developed a fascination with language at a very young age. As a student he was a leading figure of the Moscow Linguistic

Circle and took part in Moscow's active world of avant-garde art and poetry. The linguistics of the time was overwhelmingly neogrammarian and insisted that the only scientific study of language was to study the history and development of words across time. Jakobson, on the other hand, had come into contact with the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, and developed an approach focused on the way in which language's structure served its basic function - to communicate information between speakers.

1920 was a year of political upheaval in Russia, and Jakobson moved to Prague to continue his doctoral studies. There he was, along with Nikolai Trubetzkoi, one of the founders of the

"Prague school" of linguistic theory. There his numerous works on phonetics helped continue to develop his concerns with the structure and function of language.

Jakobson left Prague at the start of WWII for Scandinavia. As the war advanced west, he fled to New York City to become part of the wider community of intellectual emigrees who fled there. At the École Libre des Hautes Etudes, a sort of Francophone university-in-exile, he met and collaborated with Claude Lévi-Strauss, who would also become a key exponent of structuralism. He also made the acquaintance of many American linguists and anthropologists, such as Franz Boas, Benjamin Whorf, and Leonard Bloomfield.

In 1949 Jakobson moved to Harvard University, where he remained for the rest of his life. In the early 1960s Jakobson shifted his emphasis to a more comprehensive view of language and began writing about communication sciences as whole.

Jakobson distinguishes six communication functions, each associated with a dimension of the communication process:

Dimensions

1 context

2 message

3 sender --------------- 4 receiver

5 channel

6 code

Functions

1 referential (= contextual information)

2 poetic (= autotelic)

3 emotive (= self-expression)

4 conative (= vocative or imperative addressing of receiver)

5 phatic (= checking channel working)

6 metalingual (= checking code working)

One of the six functions is always the dominant function in a text and usually related to the type of text. In poetry, the dominant function is the poetic function: the focus is on the message itself. The true hallmark of poetry is according to Jakobson "the projection of the paradigmatic axis on the syntagmatic axis". [The exact and complete explanation of this principle is beyond the scope of this article.] Very broadly speaking, it implies that poetry successfully combines and integrates form and function. An infamous example of this principle is the political slogan "I like Ike." Jakobson's theory of communicative functions was first published in "Closing Statements: Linguistics and Poetics", in: Thomas A. Sebeok,

Style In Language, Cambridge Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1960, p. 350-377.

Jakobson's three major ideas in linguistics play a major role in the field to this day: linguistic typology, markedness and linguistic universals. The three concepts are tightly intertwined: typology is the classification of languages in terms of shared grammatical features (as opposed to shared origin), markedness is (very roughly) a study of how certain forms of grammatical organization are more "natural" than others, and linguistic universals is the study of the general features of languages in the world. He also influenced Nicolas Ruwet's paradigmatic analysis.