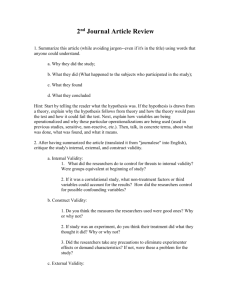

INVESTIGATING COMMUNICATION (2nd ed

advertisement