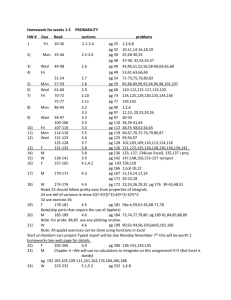

Contemporary Ethical Theory

advertisement

ARLT 100 CLASSICS OF MODERN PHILOSOPHY SYLLABUS v.1 ARLT 100: 35202D Classics in Modern Philosophy Spring 2014 MWF 9:00 – 9:50 THH 213 John Dreher, instructor Office: MHP 211 x05173 dreher@usc.edu Hours: Jan 13 – May 2 Mon 12:00 – 1:15 Wed 1:00 – 1:45 Fri 10:00 – 11:00 and by appointment Last Minute Office Hour for Final Examination Thu May 8th: 9:15 – 10:45 (MHP 211) Final Examination: Fri May 9th: 8:00 – 10:00 Materials: Required: Ariew, Roger, ‘Descartes and scholasticism: the intellectual background of Descartes’ Thought’ (hand-out) Barnes, Jonathan, Aristotle, A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press, 2000. Boyle, M.A. Stewart, ed., Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, Indianapolis, Hackett Publishing Company, 1990 Cohen, I. Bernard, The Birth of a New Physics, New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1985 Lloyd, G.E.R., Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, New York, W.W. Norton & Co, 1970 Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, abridged, Kenneth Winkler, ed., Indianapolis Hackett, 1994. (de) Montaigne, Michel, ‘Apology for Raymond Sebond’ (1580-1588) (hand-out) 2 Plato, Meno, (Anastaplo and Berns, trans. and annotators, Meno, Newburyport MA, Focus, 2004) Plato, Republic (Jowett, B.A. trans. and ed., The Dialogues of Plato, 4th edition, vol. II, Oxford, at the Clarendon Press, 1871/1953) (hand-out) Plato, Timaeus (Kalkavage, Plato’s Timaeus, Newburyport MA, Focus, 2001) Stewart, M.A., ed., Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, Indianapolis, Hackett, 1990. NB: To reduce costs, students may purchase used or different editions of required texts. This may cause some inconvenience as pagination will differ from edition to edition. Description: This course involves an intensive examination of the writings of three of the great early modern philosophers: Descartes, Boyle and Locke. All three philosophers struggled with the implications of the new science that Galileo, Boyle himself and numerous others developed during the early part of the seventeenth century. Generally, courses in early modern philosophy begin with Descartes and Locke and carry on from there. That means that little attention is paid to those who preceded the early seventeenth century greats. This is, in a way, understandable, because modern science supplanted the science that preceded it. It has often been assumed that early science was just crude, ill-informed and in just plain error. Yet we find much in early science that anticipates the great early modern philosophical theories that attempted to explain all change on a quantitative basis. Some ancient philosophers also sought quantitative explanations of change, but others, like Aristotle, emphasized qualitative explanations. We shall examine the philosophical implications of rejecting Aristotle’s vision and accepting the improvements of the early modern era. It must not be thought, however, that the debate between Aristotelians and the early moderns is finished. Much of the ancient debate is alive today, and we shall find much in it to discuss. During the first part of the course we shall examine the various approaches to science that we find in the ancient and the modern era. Mathematical treatment of the subject will be limited to examples requiring at most high school algebra, trigonometry and geometry. Tests and required papers will deal exclusively with the philosophical implications of ancient and early modern science. However, for those inclined, the three required papers (though not the tests) may be done in the history of science. We have excellent sources at our disposal in the required readings listed above; so there will be many interesting opportunities. Requirements: There will be a midterm examination, which will test for knowledge of the reading assignments as well as the expository and supplementary information deliever in class. There will also be a final examination. The first part of the final examination will test for knowledge of the reading assignments as well as expository and supplementary information delivered during class sessions following the midterm examination. The second part of the final examination will be a comprehensive question 2 3 dealing with the main theme of the course. The comprehensive question will be discussed towards the end of the semester. Class attendance is very strongly recommended. Please schedule at least one meeting with me during the course of the semester to discuss your work. There will be three short papers, approximately five pages in length. Recommended topics are: Paper #1: Explain how Plato integrates the teaching of Empedocles and Parmenides in the Timaeus. Building on that accomplishment, contrast the philosophy of science we find in the Timaeus with Aristotle’s philosophy of science. Paper #2: Why does Descartes find it necessary to justify the claim of mechanistic science to yield knowledge of the material world? Explain how Descartes tries to reconcile the apparent competing claims between science and religion while, in the very same argument, demonstrates that our confidence in science is completely justified. Paper #3: What is Boyle’s concept of scientific explanation? How is it related to his ‘mechanical philosophy’? At precisely which points does Boyle reject the earlier Aristotelian theory of scientific explanation? You may substitute a paper topic (in philosophy or the history of science) of your choosing for the recommended topic with advance permission. Grades will be calculated as follows: Paper #1 – 1/6 Paper #2 – 1/6 Paper #3 – 1/6 Midterm Exam – 1/6 Final Exam: Part I – 1/6 Final Exam: Part II – 1/6 Please remember that the University strictly prohibits plagiarism, which can be the mere failure to acknowledge the work of another as well as the deliberate misrepresentation of the work of another as your own. You must acknowledge your indebtedness not only to the ideas of others but also to their words. Schedule of Readings, Assignments and Examinations: 1. Mon Jan 13: Introduction: Ancient Conceptions of Science and Philosophy; Early Modern Conceptions of Science and Philosophy 2. Wed Jan 15: Beginnings of Ancient Science: Mediterranean Region: technology, especially metallurgy, medicine, mathematics – development of the calendar, reconciling solar and lunar divisions; ancient philosophy discovery of nature; rational criticism and discussion; Early Milesian thinkers; natural vs. supernatural explanations; 3 4 Thales’ explanation of earthquakes; Readings: Lloyd, Early Greek Science, pp. 1 – 15. 3. Fri Jan 17: The Pythagoreans, Heraclitus and Parmenides, reactions to Parmenides, Zeno, Anaxagoras, Empedocles, Leucippus and Democritus Readings: Lloyd, Early Greek Science, pp. 16 - 49 4. Mon Jan 20: M.L. King, Jr. Day: UNIVERSITY HOLIDAY 5. Wed Jan 22: Plato’s argument for innate ideas and the doctrine of remembrance; brief comparison of Plato with Descartes on innate ideas; comparison of Plato with Boyle and Locke on the origin of ideas Readings: Plato, Meno 6. Fri Jan 24: Plato’s analysis of change and truth; his way of distinguishing knowledge from belief; the significance of time in Plato’s theory of knowledge Readings: Plato, Republic, 504e – 520a/pp. 366-388. 7. Mon Jan 27: Plato’s amalgamation of Empedoclean and Pythagorean philosophy, first examples of mathematical modeling of natural phenomena, qualitative analysis of qualitative differences Readings: Plato, Timaeus, 50c – 65b/pp. 83 – 100. 8. Wed Jan 29: Eudoxus’s theory that the apparent movements of the heavenly bodies are best explained by a mathematics model constructed from by simple circular movements of concentric spheres. Readings, Lloyd, Early Greek Science, pp. 80 – 98. 9. Fri Jan 31: Aristotle’s qualitative account of the nature of matter; comparison with Plato’s Timaeus, Aristotle’s account of motions of the heavenly bodies, comparison with Eudoxus Readings: Lloyd, Early Greek Science, pp. 99 – 112. 10. Mon Feb 3: Aristotle’s theory of terrestrial motion; Aristotelian dynamics of freely falling bodies, theory of motion sustained by the continuous application of force; brief comparison of Aristotle’s theory with Galileo’s 4 5 conception of inertial force. Readings: Lloyd, Early Greek Science, pp. 113 – 15. Cohen, The Birth of a New Physics, pp. 3 – 23. 11. Wed Feb 5: Aristotle’s conception of the ‘four causes’ and their relation to scientific explanation; Readings, Barnes, Jonathan, Aristotle: A Very Short Introduction, pp. 39 – 91. 12. Fri Feb 7: Aristotle’s conception of scientific investigation; empiricism; the Aristotelian world-view, teleological explanation; why Aristotelian metaphysics appealed to the medieval Christian mind Reading, Barnes, Jonathan, Aristotle: A Very Short Introduction, pp. 92 - 117. 13. Mon Feb 10: The decision of the Council of Trent to impose Aristotelian hegemony upon the curriculum; the impeding conflict with Galileo and Boyle Reading: Ariew, Roger, ‘Descartes and Scholasticism: the intellectual background of Descartes’ thought’ 14. Wed Feb 12: Review for Midterm Examination 15. Fri Feb 14: Midterm Examination 16. Mon Feb 17: Presidents’ Day: UNIVERSITY HOLIDAY 17. Wed Feb 19: The Copernican Revolution: discovery of a heliocentric system of the planets, the significance of the telescope and microscope; discovery of the moons of Jupiter Recommended Reading: Cohen, The Birth of the New Physics, pp. 24 – 80. 18. Fri Feb 21: Galileo’s discovery of the law of freely falling bodies; the concept of inertial force Reading: Cohen, The Birth of the New Physics, pp. 81 – 126 19. Mon Feb 24: The Solar system according to Kepler; mathematical modeling, hearkening back to the Timaeus 5 6 Recommended Reading: Cohen, The Birth of the New Physics, pp. 127 – 47. 20. Wed Feb 26: First response to the new science and its method; skepticism concerning both science and religion; doubts about perception Reading: Montaigne, ‘Apology for Raymond Sebond’ 21. Fri Feb 28: Cartesian systematic doubt arising from illusion, dreaming and the possibility of a primordial evil force. Reading: Descartes, Meditiation I 22. Mon Mar 3: The Cogito, identification through change a matter of the intellect, knowledge be perception presupposes inference (viz. reason) Reading: Descartes, Meditiation II 23. Wed Mar 5: Ex nihilo, nihilo fit and the imprint theory of causation, ‘proof’ of the existence of God, beneficence of God and the rejection of the evil demon hypothesis Reading, Descartes, Meditation III 24. Fri Mar 7: Descartes’ first ‘Proof” of the existence of God Reading: handout 25. Mon Mar 10: The beneficence of God and the rejection of the Evil Demon Hypothesis 26. Wed Mar 12: The source of error; restraining the imagination within the bounds of the understanding Reading: Descartes, Meditation IV 27. Fri Mar 14: Ontological ‘proof’ of the existence of God; why systematic doubt isn’t possible, conditions of knowledge, clear and distinct ideas Reading: Descartes, Meditation V 28. Mon Mar 17: Spring Break: University Holiday 29. Wed Mar 19: Spring Break: University Holiday 6 7 30. Fri Mar 21: Spring Break: University Holiday 31. Mon Mar 24: The possibility of knowledge of the material world; role of God as epistemological guarantor; Can we have knowledge of ‘ideas’ that are not clear and distinct? Reading: Descartes, Meditation VI 32. Wed Mar 26: Criticisms of Descartes by Gassendi, and Arnauld Reading: tba: handout 33. Fri Mar 28: Criticism of Descartes by Princess Elizabeth of Bavaria and by Spinoza Reading: tba: handout 34. Mon Mar 31: Boyle’s understanding of the scientific method Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, p. 119: Boyle, ‘MS Notes on a Good and Excellent Hypothesis’ 32. Wed Apr 2: Boyle’s Defense of the Mechanical Hypothesis Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, pp. 138 – 54: Boyle, ‘About the Excellency and Grounds of the Mechanical Hypothesis’ 33. Fri Apr 4: Boyle On qualities and the mechanical hypothesis Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, pp. 1 - 52: Boyle, ‘The Origin of Forms and Qualities According to the Corpuscular Philosophy 34. Mon Apr 7: Boyle on the origin of forms Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, pp. 53 - 96: Boyle, ‘The Origin of Forms and Qualities According to the Corpuscular Philosophy’22. 35. Wed Apr 9: Boyle of Nature and God Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle, pp. 155 -175. An Essay, Containing a Requisite Digression concerning Those that would Exclude the Deity from Intermeddling with Matter) 7 8 36. Fri Apr 11: Boyle on nature Reading: Stewart, Selected Philosophical Papers of Robert Boyle pp. 176 - 89. ‘A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature’: Sections II, IV 37. Mon Apr 14: Two forms of empiricism; Locke of the Origin of Ideas Readings: tba: 38. Wed Apr 16: The distinction between simple and complex ideas; of ideas of sensation and ideas of reflection Readings: tba 39. Fri Apr 18: Locke primary and secondary qualities, perception, retention and abstraction Readings: tba 40. Mon Apr 21: Locke on space, duration, of power; his conceptions of complex ideas of substances; ideas of body and spirit terms and abstract Ideas; Berkeley’s criticism Readings: tba 41. Wed Apr 23: Locke on General Terms and Abstract Ideas: General natures, nominal and real essence; nominal essences and mixed modes Readings: tba 42. Fri Apr 25: Locke on knowledge: its scope and limits Readings: tba 43. Mon Apr 28: Locke on Demonstration and Probable Proofs Readings: tba 44. Wed Apr 30: Comparison of Descartes, Boyle and Locke; of the quantitative and qualitative views of scientific explanation 45. Fri May 2: Review for Final Examination 8