English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Sixteen Notes Goals

advertisement

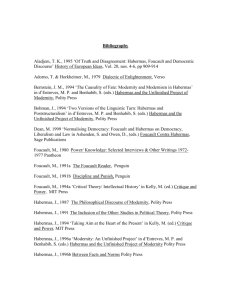

English 505 Rhetorical Theory Session Sixteen Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To begin to understand Walter Fisher’s Narrative Paradigm Theory 2) To begin to understand Ernest Bormann’s Symbolic Convergence Theory 3) To begin to understand the theories of Jurgen Habermas, especially the notions of the Public Sphere and The Life World vs. The System Questions/Main Ideas (Please Other Dramatistic Perspectives write these down as you think Walter Fisher’s Narrative Paradigm of them) Ernest Bormann’s Symbolic Convergence Theory Fisher Fisher (1987) proposed a theory of rhetoric in which dramatic stories take on the role of arguments He claimed that all people are essentially storytellers and that we constantly evaluate and choose from the stories we hear Fisher Like Burke, Fisher argued that our world is created through symbols and thus by using symbolic structures – stories – we can induce others to see the world through our eyes Fisher Stories, according to Fisher, have substance and weight because they reflect how we see our world Fisher says that humans are “essentially storytellers” Fisher That is, our rhetoric can be considered a story, with a plot, characters, and other attributes of good fiction Second, instead of using strict rules of logic, such as inductive and deductive reasoning Fisher We use “good reasons” when making decisions and persuading others Good reasons use traditional ideas about logic, along with ideas about the values the storyteller shares with his or her audience Fisher What is meant by “good reasons” varies – to some degree – among situations, genres, and media communication Finally, “the world as we know it is a set of stories that must be chosen among” Fisher Viewing communication as a narrative is meaningful for people in a wide variety of cultures and communities because “we all live out narratives in our lives and because we understand our own lives in terms of narratives” Fisher Humans use narrative rationality when evaluating the stories they hear, which is based on two standards: narrative probability and narrative fidelity Narrative probability asks whether the story is consistent with itself Fisher It concerns the degree to which the story “hangs together” In other words, this standard looks at whether the story makes sense by itself Fisher Fisher argues that stories must have structural coherence, material coherence, and characterological coherence Structural coherence refers to whether the story contradicts itself Fisher A witness who testifies in court and says something different than he or she had said previously lacks structural coherence Material coherence refers to how well the story accounts for facts that are known to be true Fisher A witness who testifies that the car in the accident was green, when all other witnesses claim it was red lacks material coherence Characterological coherence questions the reliability of the characters in the story Fisher A witness accused of murder but who is claiming innocence would be difficult to believe if he or she did not display some emotion about being accused Fisher Narrative Fidelity refers to the individual components of stories and the degree to which these components make sense to that audience Fisher Thus, probability concerns the story itself and fidelity refers to the connection between the story and the audience Fisher explains that fidelity questions “whether they represent accurate assertions about social reality” Fisher Fidelity can be understood by looking at five concepts, fact, relevance, consequence, consistency, and transcendent issue The question of fact explores the values that are embedded in a story Fisher The question of relevance concerns the appropriateness of the values to the nature of the decision The question of consequence examines the effects of adhering to a particular value set when making a decision Fisher The question of consistency asks if the values of the story confirm one’s personal experience The question of transcendent issue asks if the values in question “constitute the ideal basis for human conduct” Bormann Bormann’s theory uses a dramatic metaphor to explain how individuals use rhetoric to form common ways of seeing the world Bormann It focuses on how “Individuals in rhetorical transactions create subjective worlds of common expectations and meanings” Bormann Bormann believes that when individuals in small groups communicate, they essentially create and share stories, or fantasies, to fulfill some need The word fantasy is not used here in the conventional sense Bormann Fantasies, according to this theory, are very real events that happen to people and groups In essence, a fantasy can be defined as a shared experience between people Bormann For example, a fantasy may include experiences you and some friends had on a recent trip together, the image that CSUB projects to others, or the ideas and stories told by candidates in a political campaign Bormann Fantasy sharing is used to deal with conflict, to solidify relationships, or to express emotion Stories also help the group create a shared culture, or way of seeing the world Bormann Some fantasies are told so often that only a word or two is needed for the group to burst into laughter or understand what was meant Thus, the simple act of storytelling is an important tool for group communication Bormann Bormann theorized that group fantasy sharing can be used to explain how larger groups of people create shared visions of reality based on the stories they share Bormann A political campaign, for instance, can be viewed as a set of stories that are shared among voters Members of a rhetorical community view an unfolding fantasy much as they would a movie or a play Bormann Fantasy themes are the contents of the story that are retold by group members Sometimes, the group develops particular fantasies that have similar plot outlines, scenes, and characters Bormann These repeated patterns of exchanges are called fantasy types As the fantasy themes “chain out” among the group members, the group forms a rhetorical vision Bormann A common way of seeing the world based on the process of sharing fantasies Bormann states, “A rhetorical vision is constructed from fantasy themes that chain out in face-to-face interacting groups, . . . Bormann . . . in speaker-audience transactions, in viewers of television broadcasts, in listeners to radio programs, and in all the diverse settings for public and intimate communication in a given society” Bormann Rhetorical visions are based on typical characterizations and plot lines In fact, future fantasy themes can be based on existing rhetorical visions to spark predictable emotional responses Bormann Rhetorical critics using symbolic convergence theory to understand rhetoric must examine a number of rhetorical artifacts related to a dramatic incident Bormann Then, the critic looks for patterns of characterizations, dramatic situations, and settings The critic then reconstructs the chaining-out process to understand how rhetorical vision came to be believed Bormann Fantasy theme – Eating foods that are low in carbs can lead to sustained weight loss Fantasy type – The latest diet will help people lose weight quickly and easily Bormann Chaining out – The appearance of diet books in bookstores, new foods in grocery store, and media representations Rhetorical vision - Diets that are low in carbs are healthy and useful for managing weight Habermas Habermas’s theory, which essentially seeks to use rhetoric to ensure democracy and “complete the project of modernity” (thereby correcting the imbalances of society), uses the notion of the Public Sphere and distinguishes between the lifeworld and the system Habermas In the system, money and power dominate It includes business and commercial enterprises as well as the government, which codifies the interests of capitalists Habermas Opposed to the system is the lifeworld, which is the realm of human social interaction, such as relationships with family and friends Habermas Habermas believes that the system “colonizes” the lifeworld – our social interactions are being influenced and framed by the interests of capitalism Habermas Social pathologies or ideologies arise when attempts to “meet the requirements of system maintenance spill over into domains of the lifeworld” The system side comes to dominate the lifeworld side Habermas EX: people spend long hours working rather than being with family and friends Habermas also believes that our political discussions are influenced by the interests of business Habermas And that capitalism controls the kinds of political and personal decisions people make, which he sees as being harmful to democracy Habermas Once colonization occurs, the goal of understanding is confounded by the instrumental goal of making money and/or achieving power and status Habermas Colonization also means that there is less need for consensus through communication because disputes are resolved and decisions are made by recourse to formal regulations, laws, and especially established structures of power Habermas Mutual understanding is less likely and personal autonomy declines An example of the conflict: the ongoing debate about abortion in the U.S. Habermas Lifeworld influences are critical to the abortion debate in that each concerned party brings beliefs about religion, individual autonomy, rights to privacy, morality, and health – all dimensions of the lifeworld – to discussions about abortion Habermas Technological systems also play a role that, paradoxically, is helpful to both sides Recent developments in medical technology mean that the life of a premature infant can be saved earlier and earlier in the pregnancy Habermas Thus raising issues of viability important to pro-life advocates On the other hand, developments in abortion technology make abortions safer later in a pregnancy, a fact that benefits pro-choice arguments Habermas The resulting technocratization of the debate (a critical theorist would argue) shows the dominance of system over lifeworld and means that abortion as a right – personal or constitutional – is a fact subordinated to the technical abilities of medical experts Habermas Ultimately, Habermas seeks to develop ways of freeing our personal interests from that of business and the government The Public Sphere Habermas To counter the colonization of the lifeworld, he developed the idea of the public sphere, which involves the use of rhetoric between people who presumably have interest and knowledge in what is being discussed Habermas Additionally, the individuals are able to reach some kind of consensus about the issues, and their decision is reflected by some kind of action Habermas The practices of the European civil society in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries served as the model for Habermas’s view of the public sphere Habermas He envisions a bourgeois public sphere that would rationally discuss issues of importance to a society and advise the government on making decisions that were in the public’s best interest Habermas The public sphere acts as a check on the autocratic activities of the government and ensures that the people’s rights are protected Habermas The public sphere should carry out its deliberations using open debate in which citizens have the ability to express themselves Access and openness are critical Habermas With the advent of advanced capitalism, however, the idealized public sphere ceased to exist Habermas As private interests began to take over the political domain, the public sphere no longer was a place for rational discussion and consensus Private interests sought to influence the public sphere Habermas In turn, the public sphere lost its ability to monitor the power of the state The public sphere is instead an area where competition exists between different interest groups with conflicting goals, leading to an imbalance of interests Habermas In response, Habermas articulates a threefold schema for human knowledge, each dimension of which is necessary for an effective functioning of the public sphere Habermas Each of these interests stems from basic needs inherent in the human condition Work is the basic means by which humans provide for the material aspects of existence by manipulating various aspects of their environment and bringing it under their control Habermas Interaction is the social realm Fundamentally, humans are social creatures, and they must learn to live and function in groups to survive Habermas Language and other symbolic forms of communication are the means by which humans create and sustain social groups Thus, interaction involves using symbols to achieve mutual understanding Habermas Power or domination realizes that, because humans live in social groups, the organization of those groups necessarily creates hierarchies and thus differential power arrangements Habermas Although power or domination is just as unavoidable as work and interaction, all humans have a natural or fundamental interest in freeing themselves from unnecessary forms of power and control that manifest as distorted communication or ideologies Habermas Becoming conscious of these ideologies is the first step toward liberation from them and toward greater freedom and autonomy Universal Pragmatics Habermas Habermas then locates a rationality that can rejuvenate the lifeworld in language itself, which he terms universal pragmatics, or the study of the general or universal aspects of language Habermas His search to discover the conditions for communicative rationality in language use led him to the most elementary unit of communication – the speech act He is concerned with three major types of speech acts Habermas Constatives are speech acts that serve primarily to assert a truth claim “The grass is green” “This meeting is adjourned” Habermas The speaker tells others how things are, and the listener agrees, at least temporarily, to accept the validity of the asserted truth claim Habermas When this kind of speech act is used, the focus for the speaker is the objective world of facts or states of affairs, the speaker’s intention is to be believed, and the external world of objective facts is the focus of discussion Habermas Regulatives govern or regulate in some way the relationship between speaker and hearer in regards to shared norms – what should or should not be done Habermas Commands, prohibitions, promises, and requests are examples of this type of speech act Habermas The principal validity claim asserted in such acts is to the rightness or appropriateness of a given statement according to shared norms between speaker and listener Habermas Avowals or expressives refer to speech acts that correspond to the function of expression – to the disclosure of feelings, wishes, intentions, and the like In these speech acts, speakers make a claim of truthfulness about their internal, subjective world Habermas Validity Claims Habermas then connects speech acts to rationality by showing how each type of speech act stresses a different validity claim Habermas For Habermas, validity is a rational notion that suggests that a speech act is grounded in a particular reality domain and creates a particular relationship to the other participants in the interaction Habermas Habermas posits that these validity claims are recognized by all participants as obligations to fulfill when speaking When someone performs a speech act, all parties involved accept and operate under certain validity claims Habermas Validity corresponds to three types of speech acts Constative speech acts focus on the condition of truth Habermas Regulative speech acts are concerned primarily with the appropriateness of the norms operating in a particular context – the socially accepted rules in operation that are binding on all participants Habermas Finally, avowals raise the validity claim of truthfulness, or the obligation to show that the stated intention behind behavior is the actual motive in operation The Ideal Speech Situation Habermas In presupposing the possibility of consensual action in the process of using speech acts, Habermas suggests that every individual, in a situation in which serious argumentation occurs, is anticipating what he calls the “ideal speech situation” Habermas This situation is characterized by “(a) a lack of domination, hierarchy, internal neurosis, and external oppression; (b) equality of all participants as asserters and criticizers of truth claims; and (c) the absense of all power except the power of argument itself” Habermas Habermas’s ideal speech situation should not be taken as anything but an ideal He does not intend for the ideal speech situation to be realized in a concrete or utopian sense Habermas Rather, its value lies in its function as an assumption that is made whenever individuals enter into a conversation, thus supplying communication with a rational foundation Habermas In Habermas’s view, the ideal speech situation is both necessary and unrealized Because communication would be necessary in an ideal speech situation, it functions to regulate the interaction and facilitate the equal access of all participants Habermas At the same time, the possibility of actually achieving such symmetry and equality in all conversational encounters is unrealistic Habermas What is important is that the ideal speech situation sets up the possibility of validity claims that are negotiated and agreed upon by the speakers and hearers themselves Habermas He is able to claim that the “good and true life” – a life of truth, freedom, and justice – is anticipated in every successful act of speech Habermas Thus, he is also able to argue that “the ideal political situation is one in which citizens control their own destiny by taking an active part in the decisions that concern them” Summary/Minute Paper: