2. Morphology I) The minimal meaningful units of language: Modern

advertisement

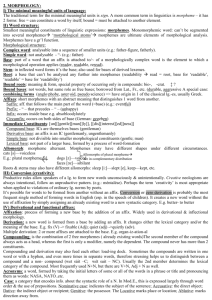

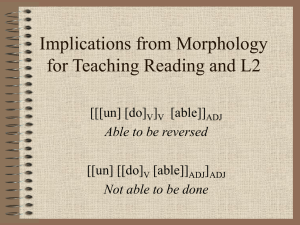

2. Morphology I) The minimal meaningful units of language: Modern linguistics Saussure: the 1st scholar to consider lg. as a structured sys. of signs. binary model of sign: ling’c sign is a mental unit, doesn’t link a thing and a name, but a concept + a phonic image (= image acoustique)later: signifié + signifiant. Ogden/Richards: semiotic triangle/triangle of signification/referential triangle/semantic trianglethought/reference + symbol (“word”) + referent (“thing”) Karl Bühler—1934—Organon Model encompasses extraling’c reality + speaker. Most people would say that the minimal meaningful unit of lg. is the word. Most linguists believe that the word is best defined in terms of the way in which it patterns syntactically. One widely accepted definition of this type of word is a minimal free form. A free form is an element that can occur in isolation and/or whose position with respect to neighbouring elements is not entirely fixed. In fact, words aren’t the minimal meaningful units of lg.; they often can be broken further. The traditional term for the minimal meaningful units is sign. A more common term in linguistics is morpheme. Word: the term can e used in at least 3 different senses: i) word1 = phonological/orthographic word (dies/died, man/men) = WORD-FORM ii) word2 = abstract unit (DIE, MAN) = LEXEME iii) word3 = grammatical ~ (come: 1. present; 2. past participle) = WORD Word1: a sequence of sounds, syllables or letters; these belong to the same abstract unit (dictionary word2); the same sequence of sounds/letters may present a different grammatical word3. Words ≠ smallest ling’c signs => consist of at least 1 lexical morpheme. The words of any lg. can be divided into 2 broad types of categories: closed and open. Closed category: function words (pronouns, conjunctions, determiners, & a few others); new words cannot be added to these categories. Open: major lexical categories (N, V, Adj., Adv.); new words can be added. Lexical item: each word that is member of a major lexical category. The variant forms of a morpheme are called its allomorphs. Free morpheme: can constitute a word by itself; bound morpheme: must be attached to another element. Type vs. token: total number of occurrence of words in a text (= ‘tokens’): far greater than number of different words (= ‘types’). Types: belong to lexical, phonological, orthographic sys. of lg. (Saussure’s langue). Tokens: belong to its concrete realisation (parole). Lexeme: abstract unit of the lexicon. Word-form: variants of lexeme on the morphological, phonological, graphemic level. Lexeme = lexical item => 1) complete sign on a particular ling’c level: the lexicon; 2) a class of variants = word-forms; 3 an abstract unit of the lg. sys. Lexeme ≠ smallest unit; may be simple, complex, or a phrasal lexeme. Complex lexemes: constituents aren’t morphemes (e.g.: hold up (a bang), put up with; idioms, etc.) can’t be decomposed into meaningful units (=morphemes), they’re formatives. Formative: any elements that has a sequence of letters. II) Word structure: Smallest meaningful constituents of linguistic expressions: morphemes. Monomorphemic word: can’t be segmented into several morphemes ‘morphological atoms’ morphemes are ultimate elements of morphological analysis. Morphemes have a gr’l function. Morphological structure: Complex word: analysable into a sequence of smaller units (e.g.: father-figure, fatherly). Simple word: not analysable - “- (e.g.: father) Base: part of a word that an affix is attached to/~ of a morphologically complex word is the element to which a morphological operation applies (reader, readable, reread). Stem: in inflected word forms it’s the base; also used for bases of derived lexemes. Root: a base that can’t be analysed any further into morphemes (readability read = root, base for ‘readable’, ‘readable’ = base for ‘readability’) Bound roots: meaning & form, special property of occurring only in compounds: bio-, -crat. ↕ ? Bound bases: not words, but same role as free bases; borrowed from Lat., Fr., etc. (durable, aggressive A special case: combining forms (anglo∙phobe, aster∙oid, pseudo∙science) => have origin in 1 of the classical lg.-es, usually Greek. Affixes: short morphemes with an abstract meaning that distinguishes 1 word from another. Suffix: aff. that follows the main part of the word (=base) (e.g.: eventful) Prefix: - “ – that precedes – “ – (unhappy) Infix: occurs inside base (Tagalog: sumulat = “write”) Circumfix: occurs on both sides of base (German: gegeben) Immediate Constituents: [un[[[gentle][man]]ly]], [[dis[[interest][ed]]ness]] Compound base: ICs are themselves bases (gentleman) Derivative base: an affix is an IC (gentlemanly, ungentlemanly) Simple base: not divisible into smaller morphological constituents (gentle; man) Lexical base: not part of a larger base, formed by a process of word-formation Difficulties in morpheme analysis: 1) –ed, -en/ good, bett- (in ‘better’)*=> manifestations of same allomorph? linguists’ proposal: these are morphs => a morpheme is a set of morphs, only morphs can be pronounced and used in performance (*: suppletive forms) 2) 2 morphological patterns are allomorphs if they express the same lexeme or same inflectional meaning 3) Cumulative expression = fusion: when an affix expresses 2 different morphological meanings (e.g.: worse: bad + inflectional meaning) Portmanteau morph: affixes & stems that cumulatively express 2 meanings that would be expected to be expressed separately. Zero expression: words in which a morphological meaning corresponds to no overt formal element (olvasø: 3rd person sing.) Empty morphemes: opposite of zero morphemes, apparent cases of morphemes that have form but no meaning (children). 1 Allomorph: morpheme alternant. Morphemes may have different shapes under different circumstances. cats [s]—voiceless Allomorphs of plural morpheme E.g.: plural morpheme [s] dogs [z]—voiced are in complementary distribution faces [əz]—sibilant Roots & stems may also have different allomorphs: sleep [i:]—slept [e], keep—kept, etc. Phonological allomorphs: described with a special set of phonological (or morphological) rules. Suppletive allomorphs: aren’t all similar in pronunciation: past participle –ed, -en; go— went; good—better (strong suppletion); buy—bough(t), catch—cough(t) (weak suppletion) III) Conversion (creativity): Productive rules allow speakers of a lg. to form new words unconsciously & unintentionally. Creative neologisms are always intentional, follow an unproductive pattern. (e.g.: mèntalése). Perhaps the term ‘creativity’ is most appropriate when applied to violations of ordinary lg. norms by poets. It’s possible for words to be formed from another without an affix. Conversion or zero derivation is probably the most frequent single method of forming words in English (esp. in the speech of children). It creates a new word without the use of affixation by simply assigning an already existing word to a new syntactic category. Derived word: a word built on the basis of a simpler one, or an affix is replaced by another. Formal operations: by ~ complex words are derived from bases. ( Non-concatenative (vs. affixation or compounding): morphologically complex words derived by ~ operations can’t be easily segmented into morphemes.) 1) Base/stem modification or alternation: part of base is modified by phonological change: voicing (houseNhouzeV), palatalising, geminating, lengthening, shortening, fronting of stem vowel, tonal change (in other languages!!) 2) Transfixation: winwon (?), digdug (?), esp. in other lg.-es 3) Reduplication: pre-, postreduplicationpart of base or the whole base is copied & attached to the base 4) Subtraction: signalling of morphological relationship by deleting a segment (or more) from base 5) Conversion: form of base remains unaltered (hammerNhammerV, bookNbookV) IV) Derivational and functional affixes: Affixation: process of forming a new base by the addition of an affix. Widely used in derivational & inflectional morphology. Derivation: more specific term for formation by affixation of lexical bases, or derivatives. Central type: an affix is simply added to a base (un + happy, read + able); other cases: derivation = replacement of 1 affix by another (baptismbaptise) 3 main types of affixes: 1) Change primary category: - Adj. + -ness = N: ‘de-adjectival N’ => nominalization (wetness, fly-by-nighter) - V + -able = Adj.: ‘deverbal Adj.’ => adjectivization (readable, old-maidish) - N + -ise = V: ‘denominal V’ => verbalization (terrorise) 2) Change subclass: She hadn’t yet become a star. — Her rise to stardom was meteoric. 3) Have no effect on syntactic distribution: unhappy, misjudge, re-read, tigress, greenish, etc. Morphological alternation: affixes can affect morphological form of base. Morphological alternants: different forms an element takes in different morphological environment. 4 types of suffix ( affect position of stress): a) Derivative follows stress rules of simple words. Stress remains: conjé cture—conjé cturalstress on penult (like in veŕandah); ́́ ́ractional stress on antepenult (like in Aḿerica) fraction—f Stress shifts: ḿedicine—med́ icinal b) Stress falls on syllable preceding suffix. ḿurder—murd́erous; ́person—perśonify c) Stress falls on suffix itself. salut́ation; Japańese; kitcheńette d) Stress-neutral suffixes. -ness, -dom, -er, -hood, -ise, -ish, etc. from Gmc. Vowel alternations: a) Alternations resulting from the GVS (15-17th c.): (reproduce opposite direction of GVS) /i//ai/: criminal—crime | /æ//ei/: profanity—profane /e//i:/: obscenity—obscene | /a//aʊ/: abundance—abound b) Vowel reduction: parent—parental, actor—actress, etc. Consonant alternations: a) Nasal assimilation: inaudible—impossible—illegal b) Velar softening: electric—electricity c) Alveolar plosive vs. fricative: transmit—transmission, invade—invasion d) Absence vs. presence of plosive with nasal: paradigm—paradigmatic Class I and Class II affixes: Class I: can occur with bound base, after stress replacement, occupy central position, trigger morphological alternation, tendency to have origin in Lat. + Romance lg.-es, attached 1st , often begins with vowel. (Exceptions: managerial, -ation-ize) Class II: stress-neutral, peripheral, origin: Gmc. Lg.-es V) Compounding: Compound base: composed of 2 (or occasionally more) smaller bases. E.g.: greenhouse (morphological compound)—written as a single word ↔ green house (syntactic construction)—written as a word-sequence; sweetheart ↔ sweet taste; cotton-plant ↔ cotton shirt. In general: 1 component is a N rather than Adj. or V. (tax-exempt: compound Adj.; baby-sit: comp. V; babies cry: comp. V) Compounds can’t be modified or have comparative/superlative forms. 2 A compound never has more than 2 constituents. (However, it can contain more than 2 words) [[dog food]N boxN], [[stone age]N cave dwellerN], [[trade union delegate assembly]N leaderN]. Hyponymy: compounds: ‘wall-flower’ wall = dependent, flower = head. Entailment: This is a wall-flower. ~ This is a flower. — BUT: not vice versa! Non-hyponymic property is a matter of lexicalization. Compounds may fail entailment: ‘hot-shot’: not a kind of shot; ‘glow-worm’: a kind of beetle. Exocentric compounds: meaning of head is outside the compound. Endocentric compound: - “ – inside => invariably result in hyponymic compounds. Subordinative compounds: (most compounds!) 1 base can be regarded as head, the other dependent. Head: normally 2nd element (birdcage vs. cage-bird). Coordinative compounds: component bases are of equal status (secretary-treasurer, bitter-sweet). Dephrasal compounds: He’s a has-been. He might short-change you, old-maidish, etc. consist of a sequence of free bases. Arise through fusion of words within a syntactic structure into a single lexical base. Compound Ns: - Noun-centred: blackbird, egghead, etc. - Verb-centred: busdriver, city-dweller, etc. N-centred: have a N as the final base Bahuvrihi compounds: spec. kind of non-hyponymic c.-s 1st base: N (N + N: egghead, skinhead, birdbrain) or Adj. (Adj. + N: lazybones, paleface) N + N: ashtray, bedtime, beehive most productive → Non-hyponymic: laybird, network → Hyponymic: handbag → Coordinative c.-s: Bosnia-Herzegovina, singer-songwriter, etc. Dvandva c.-s: Austria-Hungary, comedy-thriller mainly proper Ns referring to combination/union of referents (from Sanskrit grammar) Ascriptive c.-s: apeman, girlfriend similar to coordinative c.-s Ns + N: beeswax from genitive ‘s; almshouse plural –s; huntsman plural in origin now: boatman, doorman, etc. Adj. + N: blackbird, busyboy, greenhouse, etc. still productive V + N: copycat, crybaby: N matches up with clausal subj.; borehole, call-girl: N matches up with clausal obj.; bakehouse, payday: clausal relation would be mediated by a preposition (pay on this day, etc.); Non-hyponymic: glow-worm, copycat. V-ing + N: chewing-gum, living-room Prep. + N: after-effect | Pron./Num. + N: six-pack, he-man V-centred: V + N: pickpocket-type: scarecrow, turnkey not productive N + verbal element without suffix: bee-sting (bee: subj.), blood-shed, birth-control (birth: obj.), boat-ride (boat: obj. of Prep.) N + deverbal N in –er: gamekeeper, clothes-drier, city-dweller N + deverbal N in –ing: book-keeping, handwrting N + other deverbal N: book-production, heart-failure Unsuffixed V + Prep.: drop-out, breakthrough Prep. + unsuffixed V: downturn, intake Verbal element in –er: passer-by, bystander Verbal element in –ing: dressing down, outpouring Non-verbal element is Adj.: best-seller, shortfall Neo-classical compounds: copmpounds where at least 1 of the component bases is a combining form (CF: usually Greek or Lat. Origin). Central type: 2 combining forms (astronaut, autocrat, etc.). Initial CFs: occur in initial position (aer(o)-, audi(o)-, bio-, etc.); final CF: in final pos. (-cephany, -ectomy, -gemy, etc.) VI) Acronyms: Minor word-formation processes: Marginal in some way. Don’t yield words of a distinct morphological str. or result in new combinations of independently meaningful components. (i) Manufacture: extremely rare process, creating a new word on the basis of phonological resources of the lg.: nylon, quark, scag (AmE ‘heroin’), Kodak, etc. Simple bases, not made up of smaller units. Relation btw. form + meaning: arbitrary; not arbitrary: onomatopoeic words. (ii) Initialism: has its origin in written lg. in central cases a base is formed by combining initial letters of a sequence of words: a.) Abbreviations: CIA, DJ, pc pronounced as a sequence of letters (/si:aiei/, etc.), written as here or with full stops; occasionally spelled out as ordinary words (deejay). proper names (of institutions or places), some require def. Article (She works at the UN.) others not (She works at MIT.); most are written with upper-case letters, some with lower-case; Lat. Phrases: i.e., e.g. (id est, exempli gratia)—in lower-case; some belong to category of N & behave like Ns (MPs = members of Parliament). b.) Acronyms: NATO, AIDS, dinky (BrE: double income, no kids yet pronounced as ordinary words; mostly from proper names, some written with upper-case others with lower-case letters or either ways; Ø full stops with lower-case proper names. In some cases: not initial letters are used: TB (tuberculosis), ID (identification), etc. (iii) Clipping: cutting off part of existing word or phrase (adadvertisement; chuteparachute, etc. → Original: word that’s source of clipping; Surplus: phonological material that’s cut away; Residue: remaining material that forms new base. Still productive; often restricted to informal style, slang; can develop spec. meaning. Plain clippings: consist of just residue; Embellished clippings: other operations apply to residue to form larger words. Plain: a.) Back-clipping: surplus removed from final part: cokecocaine; mikemicrophone b.) Foreclipping: - “ – from front: busomnibus; cellovioloncello 3 Ambiclipping: - “ – from beginning + end: fluinfluenza; fridgerefrigerator Clipping: almost always monosyllabic, but few exceptions: cello, exam, medic, etc. Normally yields Ns. Embellished: clipping followed by suffix: turpsturpentine; preggerspregnant (iv) Blending: formation of a word from a sequence of 2 bases with reduction of 1 or both at the boundary btw them. 4 types: 1) paratroops: parachute + troops; 2) newscast: news + broadcast; 3) heliport: helicopter + airport; 4) motel: motor + hotel ( 1+2: can be regarded as compounds; 3+4: morphological status is indeterminate). (v) Back-formations: coining of new word by taking an eisting word & forming a morphologically more elementary word. Usually deleting affix (babysitter babysit; editoredit). Doesn’t yield distinct type of base; still productive, may result in a base that’s close in meaning to one that’s already established. (vi) Phonological modification: shift of a word form from 1 syntactic category to another may be accompanied with: a) Stress-shift: disyllabic Vs &Ns spelled alike & pronounced differently: inśertV— ́insertN; transferV—transferN, etc. In many cases, the V is older than the N. b) Vowel change: pairs of words spellt alike but belonging to different syntactic category—differentiated by vowel quality: (i) V or N: compliment, document (N /mənt/; V /ment/); (ii)V or N: certificate, estimate; V or Adj.: deliberate, desolate. c) Base-final voicing contrasts: small set of N-V pairs where N ends in a voiceless fricative & V in voiced counterpart: (i) N: belief, sheath, house; (ii) V: believe, sheathe, house. (vii) Conversion: Domain of ~: conv. normally involves changing a word’s syntactic category without any concomitant change of form. E.g.: humbleVhumbleAdj.; attemptNattemptV. Excluded: frighten: transitive V, also appears in intr. constructions. Also excluded: his couldn’tcare-less attitude. Conversion btw. Vs & Vs: Eng.: sometimes unclear which is the earlier. i) V to N conv.: arrest, go, spy ii) N to V conv.: butcher, eye, water (Instrumental Ns: knife, hammer; Ns denoting body parts: elbow, head; dynamic Vs: smell, taste, etc.) Conversion btw. Adj.-s & Ns: i) A-to-N: comic, dear, sweet ii) N-to-A: (very rare): rose, orange, the Clinton policy ‘Clinton’ used as Adj. Conversion btw. Adj.-s & Vs: i) A-to-V: dim, blind, free, narrow; dirty, muddy; waterproof; better, best ii) V-to-Adj.: amusing-amused, boring-bored, etc. (BUT: *entertained, *spoiling) Kövecses metonymy in conversion: blanket the bed, bench the players, to summer in Paris, author a new book, witness an accident, line up the class, word the sentence, ski, bicycle to town, etc. c.) VII) Case: Contrasts such as singular & plural, past & present, etc. are often marked in lg. with the help of inflection. Inflection modifies a word’s form in order to mark the grammatical subclass to which it belongs. It is expressed primarily by means of affixation. 3 criteria to distinguish inflectional & derivational affixes: - Category change: infl. doesn’t change gr’l category or the type of meaning of the word (e.g.: book-s, work-ed). - Positioning: a derivational affix must be closer to the root than infl.-al aff. - Productivity: the relative freedom with which they can combine with stems of the appropriate category. Inflectional aff.-s have very few exceptions. Der.-al affixes apply to restricted classes of stems (hospitalise vs. *clinicise, etc.). 3 common types that are expressed with the help of inflectional aff.-s on Ns: Number: morphological category that expresses contrasts involving countable quantities. singular (1), plural (more than 1) Noun class: some lg.-es divide Ns into classes based on shared semantic &/or phonological properties. e.g.: gender classification Eng.: no gender markers on Ns, but the different pronouns (he, she, it) tell us that Ns in Eng. are divided into 3 genders. Case: a category that encodes info. about the syntactic role of a N. In Mod.E., this is expressed largely through word order & the use of prepositions. Nominative case: indicates the subject of the sentence; Accusative: the direct object; Dative: the indirect object or recipient; Genitive: the possessor. The Locative marks place or location; Ablative: marks direction away from. A morpheme that encodes more than 1 gr’l contrast is called a portmanteau morpheme. The case associated with the subject of the transitive V, in some lg.-es, is called the ergative; while the case associated with the direct object & with the subject of an intransitive V is called the absolutive. The complete set of inflected forms associated with a V is called a verbal paradigm or a conjugation. Tense is a category that encodes the time of a situation with reference to the moment of speaking; voice is another gr’l contrast, the major function of which is to indicate the role of the subject in the action described by the V.Eng.: 2 voices: active (subject denotes actor or agent), passive (subject denotes a nonactor). 4