Italy - Unesco

advertisement

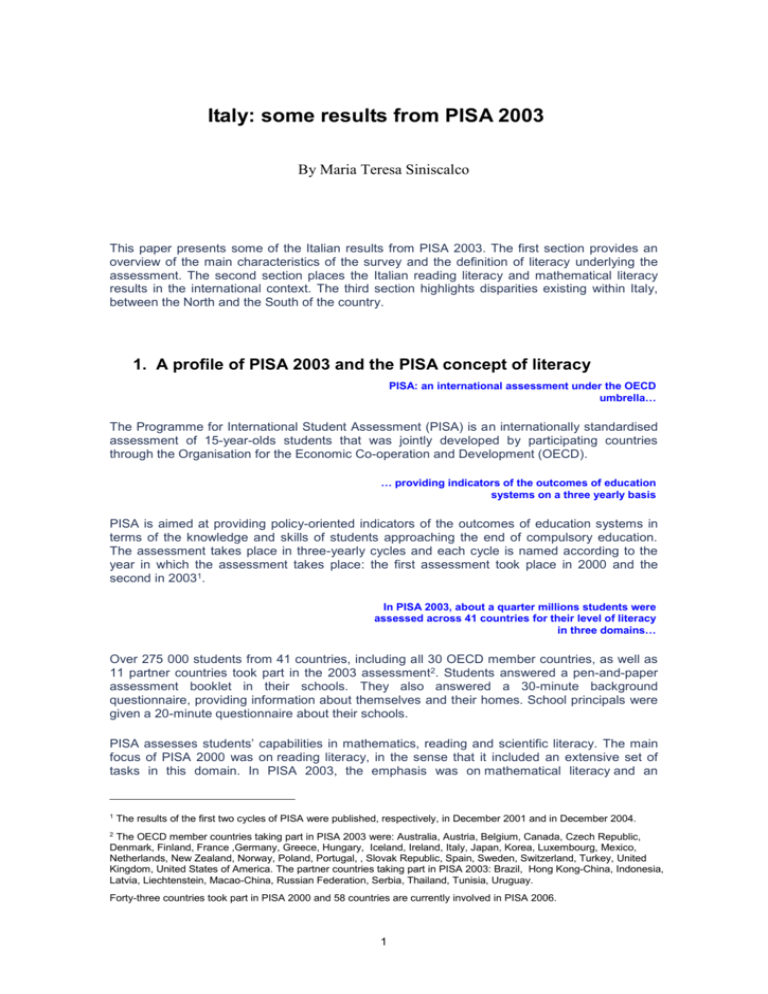

Italy: some results from PISA 2003 By Maria Teresa Siniscalco This paper presents some of the Italian results from PISA 2003. The first section provides an overview of the main characteristics of the survey and the definition of literacy underlying the assessment. The second section places the Italian reading literacy and mathematical literacy results in the international context. The third section highlights disparities existing within Italy, between the North and the South of the country. 1. A profile of PISA 2003 and the PISA concept of literacy PISA: an international assessment under the OECD umbrella… The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an internationally standardised assessment of 15-year-olds students that was jointly developed by participating countries through the Organisation for the Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). … providing indicators of the outcomes of education systems on a three yearly basis PISA is aimed at providing policy-oriented indicators of the outcomes of education systems in terms of the knowledge and skills of students approaching the end of compulsory education. The assessment takes place in three-yearly cycles and each cycle is named according to the year in which the assessment takes place: the first assessment took place in 2000 and the second in 20031. In PISA 2003, about a quarter millions students were assessed across 41 countries for their level of literacy in three domains… Over 275 000 students from 41 countries, including all 30 OECD member countries, as well as 11 partner countries took part in the 2003 assessment2. Students answered a pen-and-paper assessment booklet in their schools. They also answered a 30-minute background questionnaire, providing information about themselves and their homes. School principals were given a 20-minute questionnaire about their schools. PISA assesses students’ capabilities in mathematics, reading and scientific literacy. The main focus of PISA 2000 was on reading literacy, in the sense that it included an extensive set of tasks in this domain. In PISA 2003, the emphasis was on mathematical literacy and an 1 The results of the first two cycles of PISA were published, respectively, in December 2001 and in December 2004. 2 The OECD member countries taking part in PISA 2003 were: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France ,Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, , Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States of America. The partner countries taking part in PISA 2003: Brazil, Hong Kong-China, Indonesia, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Macao-China, Russian Federation, Serbia, Thailand, Tunisia, Uruguay. Forty-three countries took part in PISA 2000 and 58 countries are currently involved in PISA 2006. 1 additional domain on problem solving was introduced. For the PISA 2006 cycle, the focus will be on scientific literacy. …where literacy refers to a continuum of competencies applied to real life situations. In PISA, the word ‘literacy’ is used to mean much more than either the common meaning of being able to read and write or the mastery of given parts of the school curriculum. PISA defines literacy in terms of important knowledge and skills needed for full participation in society, namely “the capacity of students to apply knowledge and skills in key subject areas and to analyse, reason and communicate effectively as they pose, solve and interpret problems in a variety of situations” (OECD 2004). PISA measures literacy on a continuum, rather than something that an individual either does or does not have, considering the acquisition of literacy as a lifelong process, which takes place not just at school or through formal learning, but also through interactions with peers, colleagues and wider communities. The definitions of the different domains of literacy emphasise the real life kind of contexts to which knowledge and skills are to be applied. Reading literacy is defined as “understanding, using, and reflecting on written texts, in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to participate in society." (OECD, 2003). Mathematical literacy is defined as “an individual’s capacity to identify and understand the role that mathematics plays in the world, to make well-founded judgements and to use and engage with mathematics in ways that meet the needs of that individual’s life as a constructive, concerned and reflective citizen." (OECD, 2003). The PISA literacy continuum is described in terms of proficiency scales… For each of the assessed domains, literacy is described by means of scales representing tasks of ascending difficulty, which correspond to ascending level of ability by the students. Each of the tasks used in PISA has an associated literacy score. A student’s reading literacy or mathematical literacy performance can be expressed as a score on the corresponding scale. The scales are constructed to make the average score of all students in OECD countries equal to 500 and to put the middle two-thirds of students’ scores between 400 and 600 points (i.e. standard deviation equals 100 points). … with ascending levels of difficulty of tasks and ability of students To give more meaning to the results, students’ proficiency is classified in different levels according to their point score. These represent the kind of task that a student is likely to perform successfully six time out of ten. The Reading scale has 5 proficiency levels Box 1 summarises the five levels of proficiency in reading developed in PISA 2000. 2 Box 1 – Reading proficiency levels in PISA Level 5 (over 625 points): students are capable of sophisticated reading tasks, such as managing information that is difficult to find in unfamiliar texts; showing detailed understanding and inferring which information is relevant to the task; being able to evaluate critically and build hypotheses; drawing on specialised knowledge and accommodating concepts that may be contrary to expectations. Level 4 (553 to 625 points): students are capable of difficult reading tasks, such as locating embedded information, construing meaning from nuances of language s critically evaluating a text. Level 3 (481 to 552 points): students are capable of reading tasks of moderate complexity, such as locating multiple pieces of information, drawing links between different parts of the text and relating it to everyday knowledge. Level 2 (408 to 480 points): students are capable of basic reading tasks, such as locating straightforward information, making low level inferences of various types, deciding what a well-defined part of the text means, and using some outside knowledge to understand it. Level 1 (335 to 407 points): students are capable of only the least complex reading tasks, such as locating a single piece of information, identifying the main theme of a text, or making a simple connection with everyday knowledge. Below Level 1 (below 335 points): students are not able to show routinely the most basic type of knowledge and skills that PISA seeks to measure. These students may have serious difficulties in using reading literacy as an effective tool to advance and extend their knowledge and skills in other areas. Source: OECD 2002. The Mathematics scale has 6 levels Similarly, in PISA 2003, six levels of proficiency were defined on the mathematical literacy scale, which were described in terms of what kind of mathematical processes students can do (PISA 2003). At the lowest proficiency level, students typically carry out single-step processes that involve the recognition of familiar contexts and mathematically well formulated problems and applying simple computational skills. At higher proficiency levels, students typically carry out more complex tasks involving more than a single processing step. They also combine different pieces of information or interpret different representations of mathematical concepts or information, recognising which elements are relevant and important and how they relate to one another. At the highest proficiency level, students take a more creative and active role in their approach to mathematical problems, involving a number of processing steps. Students at this level produce a formulation of a problem, develop a suitable model that facilitate its solution and identify and apply relevant tools and knowledge in unfamiliar problem contexts. The division of proficiency scales into levels allows describing the distribution of results in terms of the percentage of students at each level and specifying which kind of tasks can and cannot be performed by students at each level. 3 2. The Italian results in the international context The percentage of students at each level of the PISA scales provides a profile of student performance Figure 1 shows the percentage of 15-year-olds in each country according to the highest level of reading proficiency that they demonstrated in the PISA assessment. Figure 1 – Percentage of students at each level of proficiency on the reading scale (2003) Finland Korea Canada Liechtenstein* Australia Hong Kong - China* Irland New Zealand Sweden Netherlands Belgium Macao - China* Switzerland Norway Japan France Poland Denmark OECD Average United States Germany Iceland Austria Latvia* Czech Republic Luxembourg Spain Hungary Portugal ITALY Greece Slovak Republic Uruguay* Russian Federation Turkey Brazil* Thailand* Mexico Serbia* Tunisia* Indonesia* 100 15 15 15 18 31 29 19 30 28 18 28 8 9 20 3 8 21 5 4 10 19 9 21 2 9 8 10 24 30 16 25 31 11 26 26 9 25 28 13 41 19 22 12 21 29 21 10 7 12 21 27 23 10 23 30 23 11 24 30 21 5 12 25 7 12 23 6 13 23 13 33 7 8 20 29 20 8 5 21 8 28 21 9 26 22 10 7 12 24 30 7 13 23 27 21 7 21 8 5 13 26 31 20 6 6 13 25 30 19 6 24 29 19 5 7 14 26 30 18 5 6 14 27 30 18 5 8 14 26 30 18 9 15 25 28 14 25 27 17 28 15 10 15 17 20 28 20 13 24 21 34 27 17 28 30 34 17 33 29 24 37 20 Lev 1 Lev 2 Source: OECD 2004. 4 6 4 5 8 4 6 2 40 16 40 16 30 11 20 27 40 5 9 2 21 25 30 11 25 31 23 4 18 20 30 24 27 25 2 6 11 31 5 8 below Lev 1 26 9 23 9 60 6 26 11 9 80 15 5 6 26 13 13 27 32 18 15 12 27 35 23 1 9 17 31 2 7 4 14 33 33 2 8 3 12 32 17 8 10 0 20 Lev 3 40 Lev 4 60 Lev 5 80 100 A lower than average proportion of Italian students score at the highest level of the reading scale… Eight per cent of students on average in OECD countries are proficient at the highest level of the reading literacy scale (Level 5), corresponding to the ability to perform complex tasks on unfamiliar topics. In Australia, Belgium, Canada, Korea, Finland and New Zealand the proportion of students proficient at Level 5 ranges between 12 per cent and 15 per cent, while in Italy it amounts to only 5 per cent. Countries with a lower percentage of students scoring at Level 5 are Spain, Hungary, Portugal, Turkey, Slovak Republic and Mexico. …while a higher than average proportion of Italian students score at Level 1 or below it At the lowest end of the scale, there are students who can at best perform very simple reading tasks at Level 1 and those who do not even reach this level, that is who may still be able to read in a technical sense, but have serious difficulties in using reading literacy in practice. On average in OECD countries, 7 per cent of students are below Level 1, while 12 per cent of students are at Level 1. Finland and Korea have the smallest proportion of students performing at Level 1 or below (about 6 per cent). Conversely, Italy has 9 per cent of students below Level and 15 per cent at Level 1, that is 24% of Italian 15-year-old do not have the foundation of literacy skills needed for continued learning and extending their knowledge horizon. Greece and Slovak Republic are countries with a similar percentage of students who can at most perform at Level 1, while this percentage is higher than in Italy in Uruguay, Russian Federation, Turkey, Thailand, Serbia, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia and Tunisia. In sum, only 5 per cent of Italian students reach the highest level on the reading literacy scale, vs. an OECD average of 8 per cent and above 12 per cent in the best performing countries. At the lower end of the scale almost one student out of four performs at or below Level 1, while on average in OECD countries one student out of five is in this situation and their proportion decreases to one out of ten in the best performing countries. The performance of Italian students on the mathematics scale follows a similar pattern Looking at the mathematical literacy results, 1.5 per cent of Italian students perform at the highest level of the scale (Level 6) and 6 per cent performs at Level 5, vs. an OECD average of 4 per cent of students at Level 6 and 11 per cent at Level 5. The proportion of students at the highest levels of the mathematical proficiency scale are even higher in the best performing countries, that is Hong Kong, Finland, Korea and the Netherlands, where more than 6 per cent of the students are at Level 6 and more than 16 per cent at Level 5. At the opposite end of the scale, 19 per cent of Italian students are at Level 1 and 13 per cent below Level 1, that is they may still be able to perform basic mathematical operations, but are unable to utilise mathematical skills in a given situation as required by the easiest PISA tasks. On average in OECD countries 13 per cent of students is at Level 1 and 8 per cent is below Level 1, while in the best performing countries, that is Australia, Canada, Korea, Hong Kong and Finland, less than 9 per cent of students perform at Level 1 and less than 4 per cent below Level 1. The mean performance score of Italy is significantly lower than the OECD average The mean score can be used to summarise the overall student performance for each country. With a mean score of 476 points the on the reading literacy scale and of 466 points on the mathematical literacy scale, Italian 15-year-old students performed significantly below the OECD average. Table 1 compares the overall student performance of Italy with that of the other participating countries in reading and mathematical literacy. The mean scores of Italy are significantly lower than those of 26 countries for reading and of 28 countries for mathematics. 5 Table 1 – Countries performing better, at about the same level or worse than Italy Countries performing significantly better than Italy Countries performing about the same as Italy Countries performing significantly worse than Italy Reading Finland Korea Canada Australia Liechtenstain New Zealand Ireland Sweden Netherlands Hong Kong-China Begium Norway Switzerland Japan Macao-China Poland France United States Denmark Iceland Germany Norway Poland Spain United States Latvia Austria Latvia Czech Republic Hungary Spain Luxembourg Portugal Greece Slovak Republic Russian Federation Turkey Uruguay Thailand Serbia Brazil Mexico Indonesia Tunisia Mathematics Hong Kong-China Finland Korea Netherlands Canada Liechtenstein Japan Belgium Macao-China Switzerland Australia New Zealand Iceland Czech Republic Denmark France Sweden Austria Ireland Germany Slovak Republic Luxembourg Norway Poland Hungary Spain United States Latvia Russian Federation Portugal Greece Serbia Uruguay Turkey Thailand Mexico Tunisia Indonesia Brazil Source: OECD 2004. 6 Both in PISA 2000 and 2003 females showed significantly higher average reading performance than males. In Italy, the female advantage amounts to 39 score points (vs. an OECD country average of 34 points), with the highest disparities, ranging between 43 and 58 points, in Austria, Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation and Serbia. In mathematics, conversely, males outperformed females in most of the countries, but the overall difference was not as large as in reading. In Italy the difference between males and females is significant, amounting to 18 score points against an OECD average of 11 score points. In six countries the difference is larger than in Italy, and in three of them (Korea, Lichtenstein and Macao-China) the male advantage is larger than 20 score points. 3. Geographical disparities within Italy Despite the considerable variation in the relative standing of countries with respect to the reading and mathematical literacy results of their students, differences between countries account for only about one-tenth of the overall variation of student performance in the OECD area (OECD 2004) . The Italian national average hides wide geographical disparities… In Italy, the mean performance scores hide significant differences between the North and the South of the country. Figure 2 presents the mean score and confidence interval for all participating countries and for five geographical sub-national areas comprised in Italy (NorthWest, North-East, Centre, South and South-Island3). …with the North scoring at the level of the best performing countries and the South lagging behind., The mean performance scores of the two Italian Northern areas are significantly higher than the OECD average, at the same level as those of New Zealand, Ireland, Sweden and the Netherlands. The mean score of the Centre of Italy is slightly higher than the Italian national average and does not differ significantly from the OECD average, while the two Southern areas have a mean score that is similar to that of Turkey and is significantly higher only of Thailand, Serbia, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia and Tunisia. Students in the North of Italy score, on average, at level 3 of the reading scale, while the mean score of students in the South of Italy lies one level below on the reading scale, at Level 2. The North-West is comprised of the following regions: Piemonte, Lombardia, Liguria and Valle d‘Aosta. The North-East is comprised of Trentino, Alto Adige, Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Emilia Romagna. The Centre comprises Umbria, Marche, Lazio and Toscana. South comprises: Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Puglia. South-Island comprises Basilicata, Calabria, Sicilia, Sardegna. 3 7 Figure 2 – Mean performance score on the reading score by Italian geographical area Finland Korea Canada Australia Liechtenstein New Zealand ITALY - North East Irland Sweden Netherlands ITALY - North West Hong Kong - China Belgium Norway Switzerland Japan Macao - China Poland France United States Denmark Iceland Germany Austria Latvia Czech Republic ITALY - Centre Hungary Spain Luxembourg Portugal Italy Greece Slovak Republic ITALY - South Russian Federation Turkey ITALY - South Island Uruguay Thailand Serbia Brazil Mexico Indonesia Tunisia 350 400 450 500 550 Note: The box shows the range within which the mean score, represented by the central line, can be said with 95% confidence to lie. Source: OECD PISA 2003 database. 8 600 The distribution of students by level of the reading proficiency scale gives a more precise picture of the geographical disparity (Figure 3). Figure 3 – Percentage of students at each level of proficiency on the reading scale by Italian geographical area (2003) 80 60 40 20 3 North-East 4 North-West 7 Centre 14 South South-Island 15 8 9 13 40 60 80 32 27 11 21 32 26 9 30 27 21 20 20 24 21 below Lev 1 0 31 Lev 1 Lev 2 20 25 11 24 8 1 Lev 3 5 2 Lev 4 Lev 5 Source: OECD PISA 2003 database. About ten students out of 100 in the North, but only 1-2 students out of 100 in the South, can perform the complex tasks required to reach Level 5. Conversely, about 12 per cent of students in the North, but more than 30 per cent in the South, reaches the end of compulsory education without having acquired the ability to use reading for learning. 9 Mathematics follows the same pattern as reading. The same pattern can be observed for mathematical literacy (Table 2). Table 2 - Mean performance on the mathematics scale by Italian geographical areas Mean score Standard Error North-West 510 5,1 North-East 511 7,7 Centre 472 5,6 South 428 8,2 South-Island 423 6,1 ITALY 466 3,1 Source: database OECD-PISA 2003. The Italian Northern areas have mean performance scores on the mathematics scale that are similar to those of France and Sweden, the Centre has a score which is not significantly different from the Italian national average, while the two Southern areas have about the same score as Turkey, performing better, among OECD countries, only of Mexico. Examining the distribution of students on the mathematics scale, only about 15 per cent of students in the North of Italy score at or below Level 1, while this is the case for almost every second student in the South of Italy, where 48 per cent of students score below Level 2. At the top of the scale, the percentage of students scoring at Level 5 and 6 are the same as the OECD average (about 14 per cent), while only 1 student out of 100 in the South area and less than 1 out of 100 in the South Island area reaches the highest levels of the mathematics scale. Both the reading and the mathematical literacy data show wide disparities between different geographical areas of Italy, which are even more striking given the presence of a highly centralised education system, as the degree of school autonomy is relatively low, with respect to other OECD countries. Outcomes disparities between the North and the South are deeply rooted in history and culture The reasons for these differences between the North and the South of the country are deeply rooted into historical and cultural factors, which are difficult to quantify and translate in terms of the socio-economic and cultural context indicators used by PISA. Differences in the socio-economic and cultural status of students and schools are not sufficient to explain, in statistical terms, the disparities between geographical areas within Italy (Checchi 2004). One macro-level indicator which is highly correlated with the average performance of the Italian geographical areas is GDP per capita (Siniscalco 2002), suggesting that disparities in outcomes should be interpreted in the light of the larger socio-economic context. 10 530 520 North-East North-West 510 Reading literacy score 500 490 Centre 480 470 460 450 South 440 South-Island 430 R2 = 0.9643 420 10,000 12,000 14,000 16,000 18,000 20,000 22,000 24,000 GDP per capita Source: OCSE-PISA 2003 database and ISTAT. However, the subsequent question is: “Where do the disparities in the level of development between North and South of Italy come from?” It may be argued, in fact, that the relationship between GDP per capita and performance on the PISA reading literacy scale is a spurious one and there is likely to be something behind both the level of development and the outcomes of education, which has an impact on both of them. A relevant analysis, in this respect, is the one carried out over two decades by Putnam and his collaborators, contrasting the functioning of democratic governments across Italian Regions (Putnam et al. 1993). This analysis highlighted the role played by the quality of “civic life” and the “civic community" in developing successful institutions: patterns of associationism, trust, and cooperation are factors that facilitate both successful institutions and economic prosperity. The evidence offered by Putnam and his collaborators show a substantial difference in the quality of civic life between the North and the South of Italy, the Northern regions being characterised by a much higher degree of civic engagement, than the Southern regions. This analysis establishes a clear link between the quality of social capital in a society and the performance of public institutions. More evidence concerning the social and economic benefits of social capital has been brought together by the World Bank (1999), showing, for example, that schools are more effective when family, community and state are actively involved (Coleman and Hoffer 1987). All of this confirms the complexity of the issue of disparities between different parts of Italy and suggests the need for long terms policies which address disparities in educational outcomes taking into account the larger societal context. 11 References Adams R. and Wu M. (eds.) (2002), PISA 2000 Technical Report. Paris. OECD. Checchi D. (2004), “Da dove vengono le competenze scolastiche”, Stato e Mercato, n. 3 dicembre 2004, pp. 413-454. Coleman, J., & Hoffer, T. (1987). Public and impact of communities. New York: Basic Books. private high schools: The European Commission (2001), European report on the quality of school education: sixteen quality indicators. Luxemburg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Ganzeboom H.B. G. Treiman D.J. and Donald J. (1996), “Internationally comparable measures of occupational status for the 1988 International Standard Classification of Occupations“, Social Science Research, vol. 25, pp. 201-239. ISTAT: www.istat.it. OECD (2001), Knowledge and Skills for Life. First results from PISA 2000, OECD, Paris, 2001. OECD (2002b) “Improving both quality and equity: insights from PISA 2000” in Education policy analysis 2002. OECD, Paris, pp. 35- 63. OCSE (2003). The PISA 2003 assessment framework: Mathematics, Reading, Science and Problem Solving knowledge and skills, Paris, OECD Publications. OECD (2004a), Learning for tomorrow’s world. First results from PISA 2003, Paris, OECD. OECD (2004b), Problem solving for tomorrow’s world. First measures of cross-curricular competencies from PISA 2003, PISA, OECD. OECD (2004c), Education at a glance. OECD Indicators, OECD, Paris. OECD and UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2003), Literacy Skills for the World of Tomorrow Further results from PISA 2000, Paris, OECD. Putnam R., Leonardi R. and Nanetti R. (1993) Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy, Princeton. Princeton University Press. Siniscalco M. T. (2003) “La valutazione della competenza di lettura dei quindicenni italiani nell’indagine internazionale OCSE-PISA”, in N. Bottani e A. Cenerini (eds.), Una pagella per la scuola, Erickson, pp. 289-338. The World Bank (1999) 'What is Social http://www.worldbank.org/poverty/scapital/whatsc.htm Capital?', PovertyNet Other publications and materials about PISA and PISA in Italy can be found on the PISA OECD website (www.pisa.oecd.org) on the Italian PISA 2003 website (www.invalsi.it/ri2003/pisa2003/). 12